40. Vintage hand-cuts without whimsies; Part 2

More jigsaw puzzle history and reports about vintage puzzles made by Chad Valley, A.V.N Jones, and the J.K. Straus Co. (about 7600 words; 64 pictures)

Part 1

Introduction

Jigsaw puzzle cutting history

An Interesting Story, made by William Peacock & Sons ca. 1908

A Sussex Village, made by William Peacock and Sons ca. 1910s

A Rough Sea, made by Raphael Tuck & Sons in the 1920s-’30s

Nativity Play, 13th Century, East Anglian Jigsaw Club 1960s-’70s

Conclusions regarding push-fit puzzles

Part 2 (this part)

Introduction and more about puzzle history

Don’t Make a Noise, made by A.V.N. Jones & Co. late 1920s - 1930s

Shiptime at Pangnirtung, made by the Joseph K. Straus Co. ca. 1940

Autumn Harvest Stored Away, made by the J. K. Straus Co. mid-1930s

The Torbay Express, made by the Chad Valley Works ca. 1928

Coming up

Introduction and more about puzzle history:

Part 1 of this two-part series focused on the types of jigsaw puzzles for adults that were made during the jigsaw jag craze that peaked in about 1909. Before about that time they had been mainly thought of as tools for children’s education, moral improvement, and for developing young people’s reasoning and fine motor skills.

After a burst of enthusiasm that was called a Craze at the time jigsaw puzzles remained popular both as a social and solitary recreation for grown-ups, but no longer at the initial ephemeral “craze” level. Some of the makers who had jumped on the jigsaw-puzzle bandwagon moved on to other activities, but others joined in as demand for them continued to be fairly steadily for the next 20 years. New styles of puzzle cutting and new approaches to marketing emerged.

The most popular new cutting style was actually already quite old at the time – making the pieces interlock by interrupting the cut-lines with protruding knobs that had narrower necks. This had already been done for about 100 years in the didactic children’s map puzzles, but mainly only on the outside edge pieces (see above photo.) The interlocking pieces formed a stable frame within which the push-fit dissected maps could be more easily assembled, thus combining learning geography with developing fine motor skills.

When puzzle-makers first began making jigsaw puzzles for adults they thought that such interlocking was unnecessary, and possibly insulting, for their new target adult market. But as puzzles grew in size in terms of number of pieces, and the pieces became smaller, the challenge of the instability of push-fit grew exponentially. Small lightweight pieces do not get held in place by as much gravity and friction as larger ones. And an assembly island of push-fit pieces can be a real challenge to move when its proper location is found.

I don’t know which company first began to make interlocking pieces in their puzzles for adults, but as you can guess, when that innovation proved to be very popular with the general public the other companies soon copied it. By the late 1920s the house style of almost all of the puzzle companies was to make their puzzles interlocking, and the words “fully interlocking” began to feature prominently on many company’s box-tops as if it were a claim to superior design.

Making interlocking connectors greatly slows down the puzzle cutting process. Since cutters were paid by the piece, if one of them developed a new format that was a quicker way to cut fully-interlocking puzzles his or her colleagues would also adopt it. The fastest cutting method the company would permit would evolve into that manufacturer’s house style, at least for its less expensive series.

Some companies wanted to compete on the basis of higher quality rather than lowest cost. They would pay their cutters a higher piece-rate but require them to use more elaborate and less efficient cutting techniques. Those may or not be fully interlocking. High quality cutting included both the long-established method of colour-line cutting as well as another new/old technique that was gaining fans – including figural pieces (whimsies) in puzzles.

As explained in Part 1, including whimsies was not used extensively by the manufacturers (as distinct from independent craftspeople) back then. In the 1920s, as far as I can tell, Britain’s Zig-Zag Puzzles and G.J. Hayter’s “Victory” brand, and Parker Brothers in America (Pastime Puzzles), were the only major factory-made puzzles that included the risky figural pieces in their higher-end ranges.

In addition to competing on the basis of price and quality the companies also competed using marketing techniques. Their jigsaw puzzles for adults were sold in toy shops, book stores, department stores, newsstands, and other retail locations. At first, in keeping with the belief that grown-ups wanted to discover the image as their assembly progressed, puzzles for adults were sold in rather plain boxes with just the company’s brand and the puzzle’s name given as clues as to what the buyer could expect. In doing so the companies were mimicking the way that puzzles made by independent craftspeople, including the very best ones, were being packaged. That approach depended mainly on brand loyalty and brand reputation to get people to choose their puzzles from the others ones that were available on the store shelves.

In the 1910s and ‘20s some of the manufacturers began to give their puzzles more eye-catching packaging, both to inspire impulse buyers and to attract customers away from their competitors. For some companies that just meant using more colourful wallpaper to clad their cardboard boxes, but some put artwork on their boxtops showing high society or middle-class people enjoying assembling jigsaw puzzles:

I suspect it was from shopkeeper feedback that companies learned that many customers would prefer getting an idea of what the image of the puzzle would be before making their purchase decisions. In the 1920s some manufacturers started to include small black &white pictures of the puzzles’ image on the top, end, or bottom of the box. See the Chad Valley box-top on the lower-left corner of the above photo for an example of this.

In 1929 an American stock market crash led to financial panic and a worldwide economic tailspin. Unemployment soared. In her 2004 book The Jigsaw Puzzle: Piecing Together a History economics professor (department Chair at Bates College) and jigsaw puzzle historian Anne D. Williams observes that even those who were employed faced job insecurity and lost income: The average work week in the US dropped from 48 to 35 hours from 1930 to ‘34, and there was a 20% reduction in average hourly wages.

Prof. Williams goes on to quote a January 1932 article called Popularity of Adult Games Reaches New High in the trade magazine Toy World:

People are being forced to curtail expenses. In place of the usual theatres, picture shows, dining and dancing, adult games are being substituted, for people must have their amusement and when they haven’t the money to spend for expensive forms you will find them more interested in the inexpensive.

She goes on to note that there is a big psychological element too.

Puzzles and games diverted people from their problems. Even better, these pastimes allowed for success in a dismal and dreary time when economic failure was the rule. Finishing a jigsaw puzzle or winning a game gave the player a sense of mastery and achievement that was hard to come by in other facets of daily life. Puzzling and game playing within the family or among friends also provided a comforting network of support when economic troubles were tearing at the social fabric.

I think that another important factor may have been that everyone knew that the new jigsaw puzzle was something that nearly everyone was enjoying during those lean times, even rich industrialists, the US president, and the Royal Family. Also, now puzzling at home could be accompanied by another fast-growing form of entertainment - Radio!

As in the 19oughts craze, unemployed woodworkers hauled out their neglected scroll saws to turn making jigsaws into a moneymaking activity. Also, the 1920s had seen an upsurge in home crafts, and hobbists had learned how to make them from articles and columns in craft magazines and Popular Science. Anne D. Williams has identified over 500 such short-lived Depression-era businesses in the US. The large-scale jigsaw puzzle manufacturers were in competition with these semi-professionals, as well as with each other.

Competition was fierce during those lean times and the manufacturers adopted new packaging to show off their professionalism. Those small black & white photos from the 1920s quickly evolved into something that is now ubiquitous in the world of both die-cut cardboard and laser-cut wooden puzzles – filling the box-top with a colourful and useable guide picture to aide in assembly:

The biggest characteristic of how the 1930s’ craze was different from the earlier one was manufacturers’ ability to make relatively low cost wooden jigsaw puzzles due to their factory efficiency. Between that and and a surge in production of small cardboard puzzles, they were able to make the demand for jigsaw puzzles reach right down to cost-sensitive working class folks.

Despite the introduction of cardboard puzzles that had puzzle-pieces similar to strip-cutting, sales of plywood puzzles surged and they remained the most popular format (because the hydraulic presses that were needed for die-cutting were not very strong at that time so they had to use thin cardstock, and the quality of cardboard then was not as good as it is now.) As today, durable wood puzzles could be traded or re-sold for almost as much as they had cost new, or they could be justified as a long-term recreational investment in expected multiple future assemblies. They also became something one could inexpensively rent from privately-run clubs and libraries (another 1930s innovation which I discuss here in my write-up about Royal Route to the West.)

I don’t know whether it was a correct interpretation of the marketplace or not, but the puzzle makers interpreted this emerging and profitable demand from the working class as being different from their traditional high-society and middle-class customers. Perhaps they believed that poor people were more likely than “their betters” to be parted from their money with colourful cover pictures. Or perhaps they believed that people with “more refined” tastes still wanted to discover the image for themselves but working class people wanted (or needed!) guide pictures to help them with assembly. But for whatever reason, in the 1930s a very clear pattern developed: Inexpensive puzzles (simpler cutting patterns and thinner wood) tended to be packaged with cover pictures that depicted the puzzle’s image, and the more expensive ones were still packaged without guide pictures.

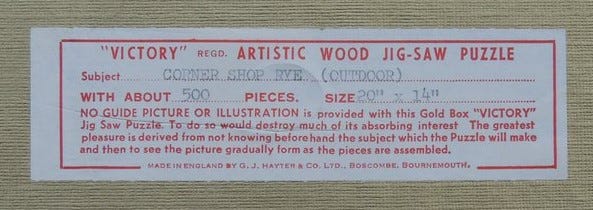

Gerald Hayter’s “Victory” brand jigsaw puzzles illustrate this. His company began as a workshop that made high quality puzzles and Hayter himself was a pioneer in cutting figural pieces (whimsies) in his puzzles. In the early 1930s he ambitiously expanded, setting up a factory that was staffed by cutters that he trained to use the very highly efficient strip-style cutting method (that he also may have invented) to make fully interlocking puzzles. Coinciding with this he changed the styles of puzzles that his company would offer, adding children’s puzzles as well as new and inexpensive series of puzzles for adults that he called “Popular” and “Topical.” These were strip cut without figural pieces from thin 3ply plywood and they were always packaged with the puzzles’ image on the cover.

The company’s more expensive puzzles, called the “Artistic” series, were a simplified version of his own previous high quality cutting style. They were made with ¼” (5-6mm) 5ply wood, the cutting included (rather crude) whimsies, and they were packaged in distinctive sturdy gold-foil covered boxes with the absence of a cover image explained on the end-label as follows:

In the mid-1930s Hayter introduced a new and even more expensive series called “Super-Cut”, that was also packaged in the distinctive gold boxes without images, which was basically a return to the high-quality cutting that he had done himself in his workshop days before establishing a factory.

This posting does not include any Victory puzzles. The only Victory puzzle that I have done from one of their inexpensive no-whimsy series is Houses of Parliament and I have already reported about it here. You can learn more about G.J Hayter and Victory puzzles from my introduction to that posting, or from an essay I wrote about Hayter and his company that I published here.

Don’t Make a Noise made by A.V.N. Jones & Co.

maker – A.V.N. Jones & Co. – Delta series London, England

date – 1930s or late 1920s

312 pieces (count) 9½” x 16” (24.5 x 40 cm) about 3.1 cm²/pc 3mm 3ply

interlocking strip-cutting with wavy cut-lines and horizontal glides

artist – Herman Kaulbach ca. 1890

The artwork on this box top seems to suggest that it is a children’s puzzle but that is certainly not the case. In fact, A.V.N. Jones & Co. used this same artwork, including the subtitle “a pastime for young & old,” for the boxes of its Delta puzzles as large as 2000 pieces. In my experience the average toddler would not have the patience for such a challenge. Heck, I don’t either!

For me, the most interesting thing about Don’t Make a Noise was its appealing image and the story about the artist. But before discussing that I’ll analyze its efficient cutting design and give you an illustrated walkthrough of my assembly.

(Note: The following observations came from studying the cutting pattern after I had completed the puzzle. I try to avoid letting my brain go into analysis mode during assembly. I also try to avoid letting my brain go into judgmental mode, but that is sometimes rather difficult to do when I know that after it is done I’ll be writing a puzzle review.)

Don’t Make a Noise was cut in the 1930s or perhaps the late 1920s by a worker at the A.V.N. Jones & Co. factory in the Enfield borough of London, England. You will recall that cutters who worked in puzzle factories were paid by piece-work and therefore had an incentive to cut as many puzzles as possible during a shift. Some cutting styles are much more efficient for making pieces than others.

If you look closely at the above photo of detail from this puzzle you will see that it is continuously cut into rows with a wave-like rhythm, occasionally interrupted by cutting knob connectors pointing up or down. Continuous cutting like this is very quick and efficient, enabling the cutter to make more puzzles in a shift. Periodically skipping cutting the knob connectors (which I think of as “glides”) makes the cutting go even faster than regular strip-cutting but it does mean that the puzzle cannot be promoted as being fully-interlocking.

The vertical cuts can also be continuous slowly waving lines, interrupted by a connector for every row. Strip cutting and glides can be done in a variety of ways. If the horizontal and vertical cuts were straight instead of wave-like the cutting design would look far less interesting, like this:

Below is another strip-cut puzzle, An Old Persian Love Lyric cut by the Lord Roberts Memorial Workshops for W.E. Mack’s Cavalcade puzzle series, with the vertical glides being very small waves instead of large ones, and the horizontal cuts to make connectors for every column appear to have been cut from a column one piece at a time. Since this puzzle was made by disabled WWI veterans in a sheltered workshop the cutting was possibly done in a more assembly line style than usual with the horizontal and vertical cuts being made by different individuals.

So, Don’t Make a Noise is the strip-cut cutting design that is similar to die-cut cardboard puzzles, but with wavy grid lines and skipping some of the vertical connectors. All of the pieces have four sides and four corners, but the glides mean that not all of them have a connector on each side. When you are looking at them this gives the impression that every piece has an interesting and unique shape, and after assembly the waves and glides disguise the basic simplicity of the cutting design.

Add their efficient cutting to having made this puzzle from thin 3mm plywood, use of an aggressive fast-cutting sawblade (you can see the ragged cutting edges if you zoom in on any of the following photos), and stack cutting which enabled the cutter to make of up to four puzzles at a time (as evidenced by “pinholes” you can see in the above detail photo) and A.V.N. Jones was able to sell these “Delta” series puzzles at a fairly low price point.

I had not noticed all of this when I bought this puzzle (for less than £20!) or when I assembled it. I was most entranced by its charming image. Here is how my assembly progressed:

The puzzle was an entertaining build but throughout assembly I was aware that the image is an incomplete story: What is that little girl trying to trap with her father’s hat? Is this suspenseful composition the artist’s intention, or has the image been cropped?

The painting has a barely legible signature in the lower left-hand corner – Kaulbach. With some research I found two 19th century German artists with that name and by comparing their painting styles I was able to determine with a fairly high degree of confidence that this was painted by Hermann Kaulbach (sometimes called Herman von Kaulbach.) But when searching his paintings I was not able to find this one.

When I loaned the puzzle to my friends Greg and Beth Skala they had the same thoughts about it being an incomplete story but Beth took a different approach to her online research. She took a photo of the completed puzzle and used it for a Google image search. She found it. Don’t Make a Noise is indeed a cropped painting made by Hermann von Kaulbach in 1890:

The painting had been collected by Captain Frederick Papst, that generation’s owner of the Papst Brewing Company of Milwaukee which had been founded in 1844, and his wife Maria. At the time the couple were having a new mansion built for them (which is now a historic house museum) and they were on an art buying spree to fill its walls.

According to this blog:

During the construction of their mansion, arguably one of the most important houses in Milwaukee, the Pabsts were set on filling their home with artwork. Captain Pabst and his wife were beginners to the art scene, but they knew what art they each enjoyed and bought according to their personal taste. …

Once becoming enamored by the art world the walls of his home, brewing company, restaurant and other establishments were covered with works of art. … In addition to promoting the city’s art scene, he saw the advantages of advertising his brand through the beauty of art. Pabst’s personal painting The Little Trapper, by Hermann Kaulbach, was used to promote Pabst Malt Extract at the turn of the 20th century. Pabst offered a lucrative deal of buying six bottles of Pabst Malt Extract to receive a free reproduction of the painting now labeled Baby’s First Adventure. He was successful in dispensing thousands of copies to loyal customers. It was an inventive business method at the time and Pabst was one of the first to ever do it.

As for Hermann Kaulbach (1864-1909) he was the only son of Wilhelm von Kaulbach, a noted historian, book illustrator and muralist who was later appointed Director of the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, which was recognized at the time as being one of the finest art schools in Europe. Hermann’s own training came from that Academy where he became a protégé of Karl von Piloty.

Being Academy-trained, Kaulbach’s initial specialty was historical paintings and his mastery of that form brought him a professorship at the same prestigious institution. It may not have enhanced his academic reputation but his income certainly improved when he turned his attention to genre paintings of cheerful ordinary life, especially ones featuring children of which this is a fine example. Since historical paintings are currently so very out-of-fashion, he is now mainly remembered for this style.

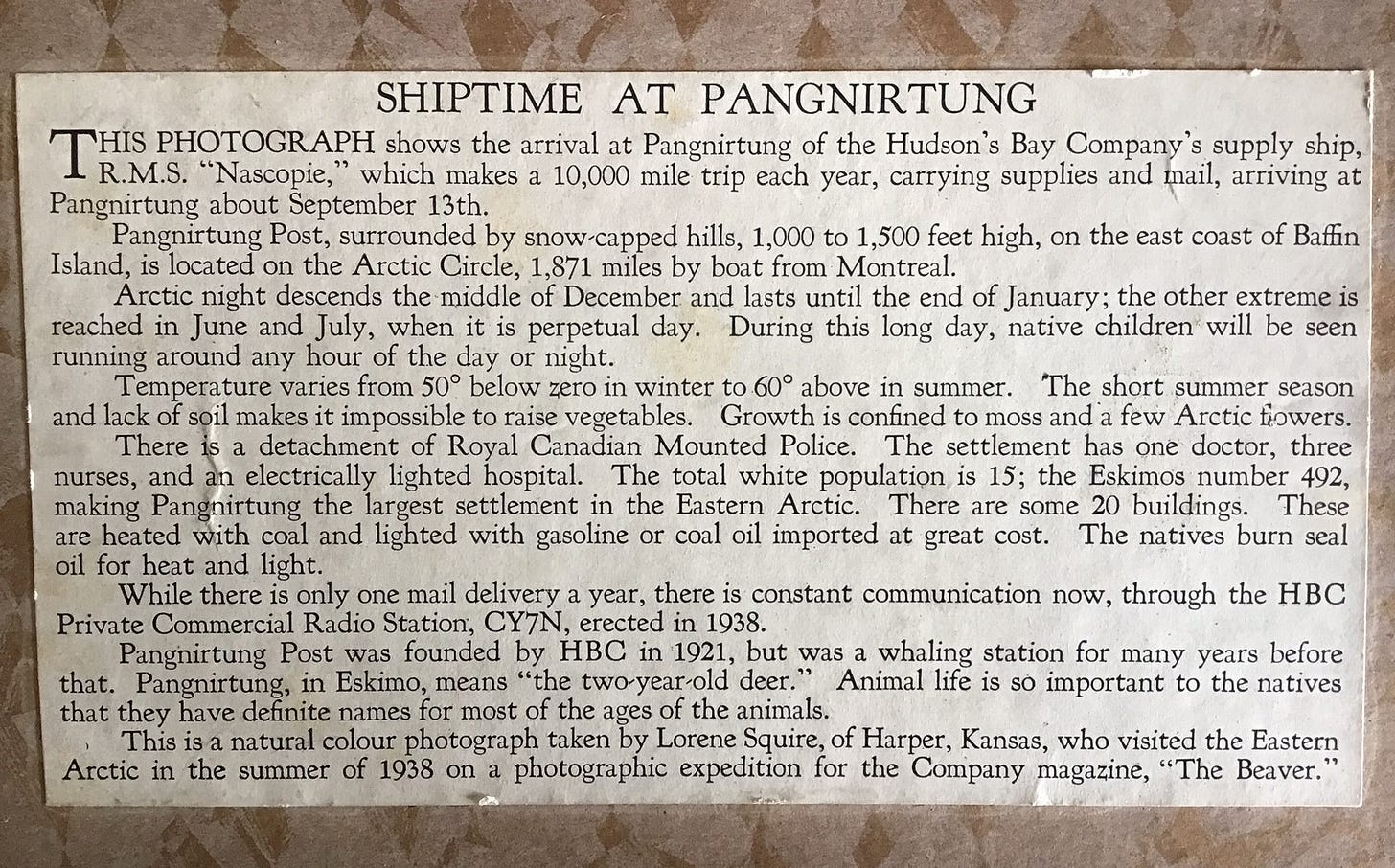

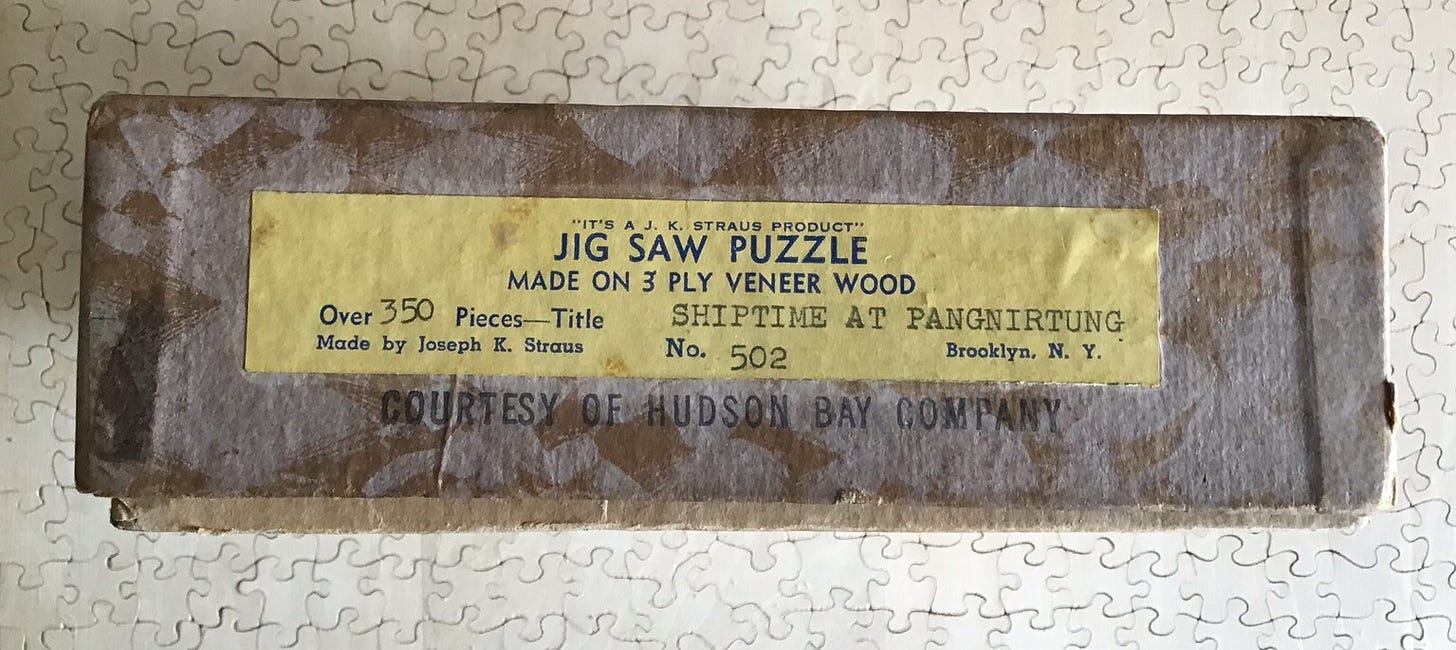

Shiptime at Pangnirtung made by the Joseph K. Straus Co.

maker – Joseph K. Straus Company Brooklyn, N.Y.

date – unknown (1940s?)

~250 pcs 12” x 18” (31x45.5 cm) 5.6 cm²/pc 5mm 3ply

interlocking grid-cut with crooked lines; no figural pieces

image – 1938 photograph by Lorene Squire

I have previously reported about two other Straus company puzzles here. The Straus company was located in Brooklyn, NY and was run by him and his wife for over four decades, from 1933 until 1974. Anne D. Williams describes them as having been “one of the largest American producers of wood jigsaw puzzles in the post-World War II years.” But that may be more due to the company’s longevity and their post-war survival primarily as a maker of children’s puzzles. I have not been able to get a sense of the scale of Straus’ operation as a maker of adult puzzles in the 1930s and ‘40s but they must have been fairly large since they are a fairly common brand of vintage American jigsaw puzzle to come up type for sale these days.

Joseph K. Straus’ (1879-1957) career began at the age of sixteen as an employee of Ullman Manufacturing. They were a fine art publisher and manufacturer of “framed pictures and art novelties.”. During the first jigsaw puzzle craze in the 19oughts that company had been the maker of Society brand jigsaw puzzles. I don’t know if Strauss began as a cutter but in 1906 he became a sales representative for the company.

In 1933 he and his wife set up their own puzzle business, renting space in a corner of the Ullman company’s factory. I don’t know whether Ullman was still making puzzles at that time but Straus was immediately able to sell his puzzles nationwide because of his contacts with industry buyers. In their later years, Straus’ products included cardboard children’s puzzles, making them the only hand-cutting company anywhere that I know of which adopted die-cutting technology.

Now onto this puzzle itself. I wonder whether the stamp below the label at the end of the box (see above photo) is just an acknowledgement that the photo is licensed from the HBC, or whether the puzzles were made for the HBC as a special order, for example to be distributed to shareholders at the company’s annual general meeting. The unusual text about the puzzle on its box cover makes me suspect it may be the latter.

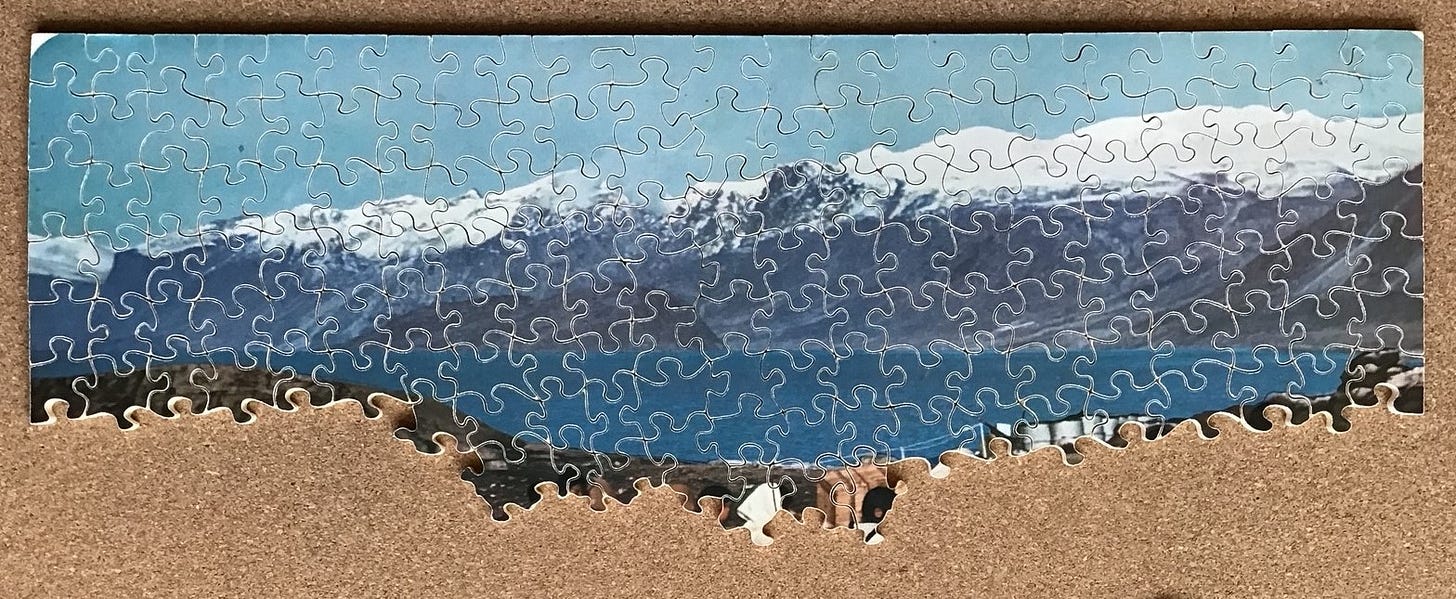

Here is my assembly walkthrough. I began with my usual flipping and sorting except that I lined up the potential edge pieces on the top and sides of the board because I planned to begin with the focus of attention of the image:

I began with pieces that had text and a few other targets of opportunity:

Nothing emerged as a focus of attention and there were no promising colours or textures in the presumed middle- or foreground that looked promising, so this approach proved incredibly slow going. Oh well, I had remembered enough about what this image looked like from when I had bought it to know that this approach had been a long shot anyway. Change of plans: I’ll work on the sky:

And then the dark blue-grays that seemed to be the sides of the distant mountains, and the featureless dark blue that turned out to be water:

It was at this point that things slowed down again. As for the cutting design, after my long rant at the beginning of my write-up about Don’t Make a Noise you can probably notice, as I did, that this puzzle was made with grid style cutting design that is somewhat disguised by having rather chaotic but continuous strip lines. So I decided to again switch assembly strategy, this time to the edge first approach which is usually effective for grids.

Then assembly was just a matter of colour and shape matching from a dwindling stock of loose pieces:

This puzzle was an enjoyable assembly, not-so much because of the cutting design but because there was challenge that came from the confusing composition of people and parcels in the foreground. I also appreciated that the image depicts an important part of Canada’s heritage.

I later learned that the strip style in this puzzle is typical for the Straus’ puzzles which were primarily made to be sold at an affordable price-point. But they also made puzzles with a more elaborate cutting (see next puzzle) including two-layer puzzles that are now much sought-after by collectors. This puzzle therefore doesn’t have a very creative cutting design, but it is well executed. Its fully interlocking pieces were cut with a very fine sawblade so the narrow kerf (the swath cut by the saw) makes this one of those that can stay intact if it is lifted up by a corner. (I’m sorry I didn’t take a photo of that.) Also, it is nicely sanded so that it has a luxurious tactile feel.

The information on the box cover (you did read it didn’t you!) led me into interesting post-assembly research into the photographer of this puzzle’s image. The image is a photograph taken in 1938 by Lorene Squire that was used in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s 1940 calendar.

It was taken when she was on one of three photographic expeditions she undertook commissioned by the HBC’s magazine The Beaver, now published as Canada’s History. I well remember The Beaver from my childhood. National Geographic, Life, and The Beaver were among the very few magazines that my parents subscribed to. My father was an ardent amateur photographer, with his own darkroom, and my parents were also proud of our French-Canadian ancestry.

Squire was primarily considered to be a nature photographer who specialized in wildfowl, but for that expedition she was instructed “in addition to your specialty, you would do a more or less routine record of life in the north as you see it, and hitherto unphotographed [HBC] posts.” Fulfilling that mandate expanded Lorene’s photographic style and she took many candid shots of HBC employees and events, including people relaxing and socializing aboard ship, and photos of the indigenous Inuit people portraying them in a much more sympathetic way than had been typical for The Beaver up to then.

That broader subject matter enabled her to begin to escape being typecast as only a wildlife photographer, getting commissions from wider-circulation publications like Country Life, Canadian Geographic Journal, and The Saturday Evening Post. Unfortunately, only three years later, just as her career was taking off at the age of 32, she died in an automobile accident while on an assignment in Oklahoma for Life magazine. She had not yet fully developed a reputation as a versatile photographer: Her New York Times obituary described her as “one of America’s foremost photographers of wild life.”

You can learn more about her and see more of her photos in this article, this photo-essay, and in this 19:15 minute YouTube video.

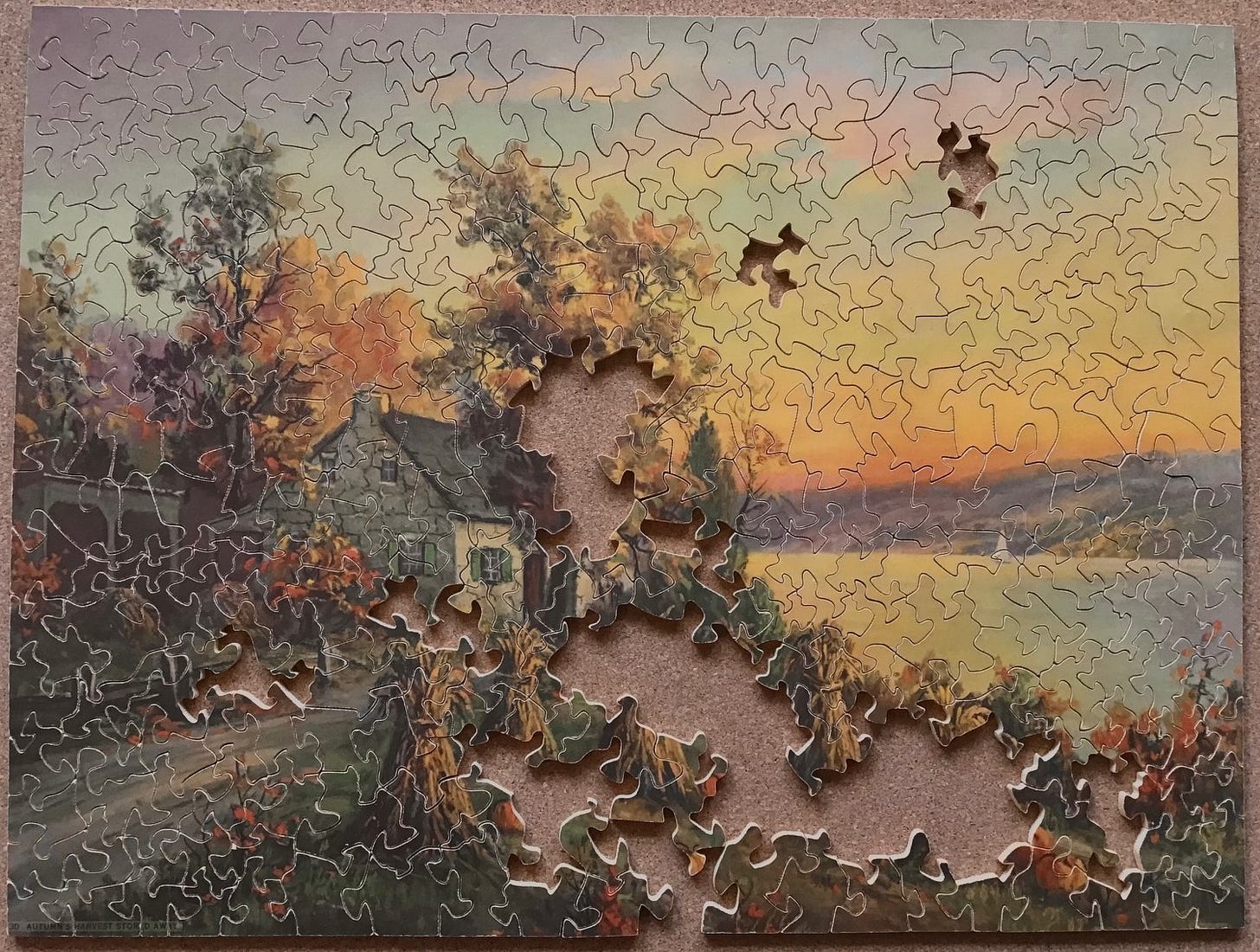

Autumn Harvest Stored Away made by Joseph K. Straus Co.

maker – Joseph K. Straus Company Brooklyn, N.Y.

artist – unknown

date – mid-1930s (based on box colour and stock number)

~300 pcs 12” x 15½” (30 x 40 cm) 4 cm²/pc 4½ mm 3 ply

free-form cutting; no figural pieces

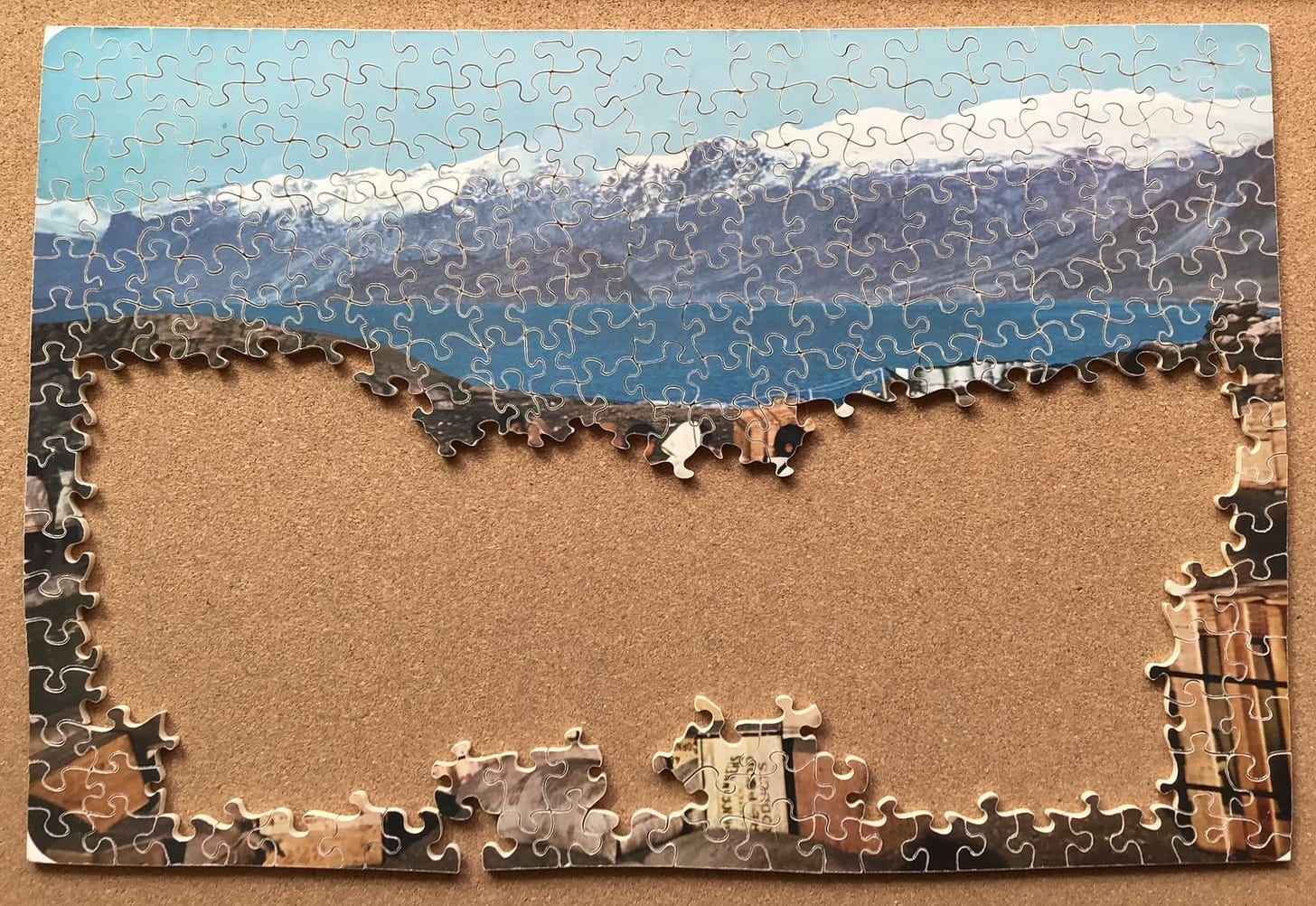

incomplete - 5 pieces missing

I got this incomplete Joseph K. Straus puzzle for free when someone used it to help fill up the shipping box while sending me a bunch of used puzzles I had bought. Used puzzles that are known to be incomplete would be the ultimate “frugal option” – they sell extremely cheaply, but unfortunately of course, they have the huge downside of denying the satisfaction of completing the puzzle. I’m thankful I don’t need to be that frugal! I buy puzzles online only from vendors who include a photo of the completed puzzle. That way I not only know that it is complete but also can assess how much I would like the cutting design.

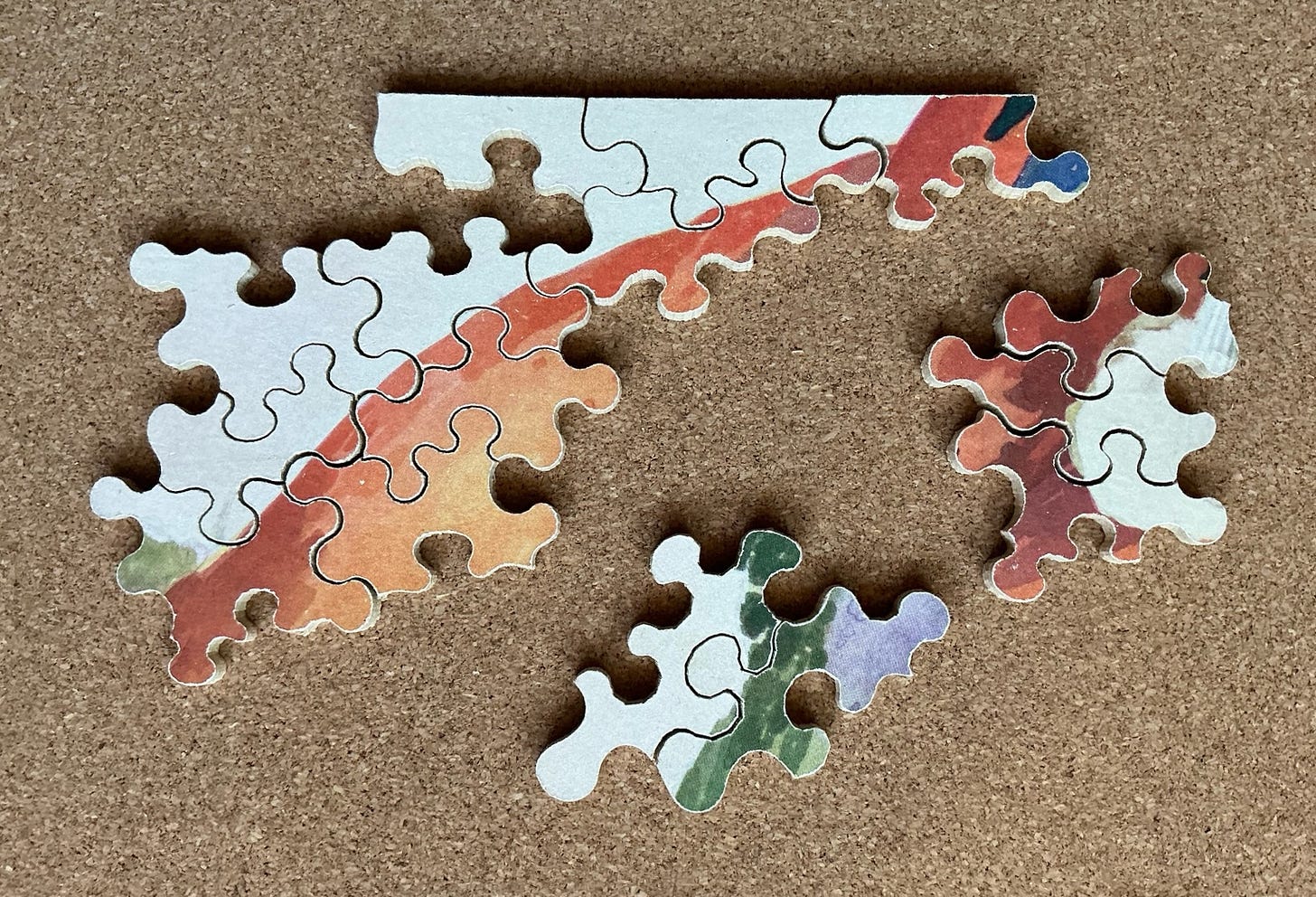

I am including this puzzle here because it was part of my recent vintage puzzle binge, and because it was a good build despite the lack of a happy ending, but most importantly because it shows the kind of interesting cutting pattern that Straus’ company was capable of for its higher-end puzzles. American puzzle expert and restorer Bob Armstrong describes a Straus puzzle with cutting similar to this one as having the company’s “early, more interesting cutting style.” In my imagination I like to think that it may have been cut by Joseph Straus himself.

The image is nothing special, but the cutting design which is not like anything I have seen to date made assembly both challenging and very enjoyable. As you can see, this puzzle is nearly fully interlocking, but it is certainly not strip cut. I can’t even recognize where the cutter made a continuous cutline from top to bottom or side to side to sever the puzzle-blank in half and quarters to make cutting easier. There are places where the cut-lines cross each other so I don’t think that the cutter made every piece individually, as in the next and final puzzle in this essay, but I think it is a very interesting cutting design. What a great thing to get for free!

Now (finally!?) I get to the assembly. The very plain red-orange box, standard packaging for the Straus company in the 1930s and early ‘40s, gave no hint of the treats to come:

Since I had absolutely no idea of what the image would be, or whether or not its image would even have a focus of attention, I decided to begin with edge pieces. (Sorry about the poor lighting in the photos!)

I can’t recall whether or not I was told when it was sent to me that this free puzzle would be incomplete. I probably was told, but I have often acknowledged my amazing capability for forgetfulness. In any event, if I was told when I started this puzzle had forgotten. It was at about the stage in the following photo that I began to suspect it was incomplete because there were no more sky-coloured pieces left …

… and by this stage I was sure of it:

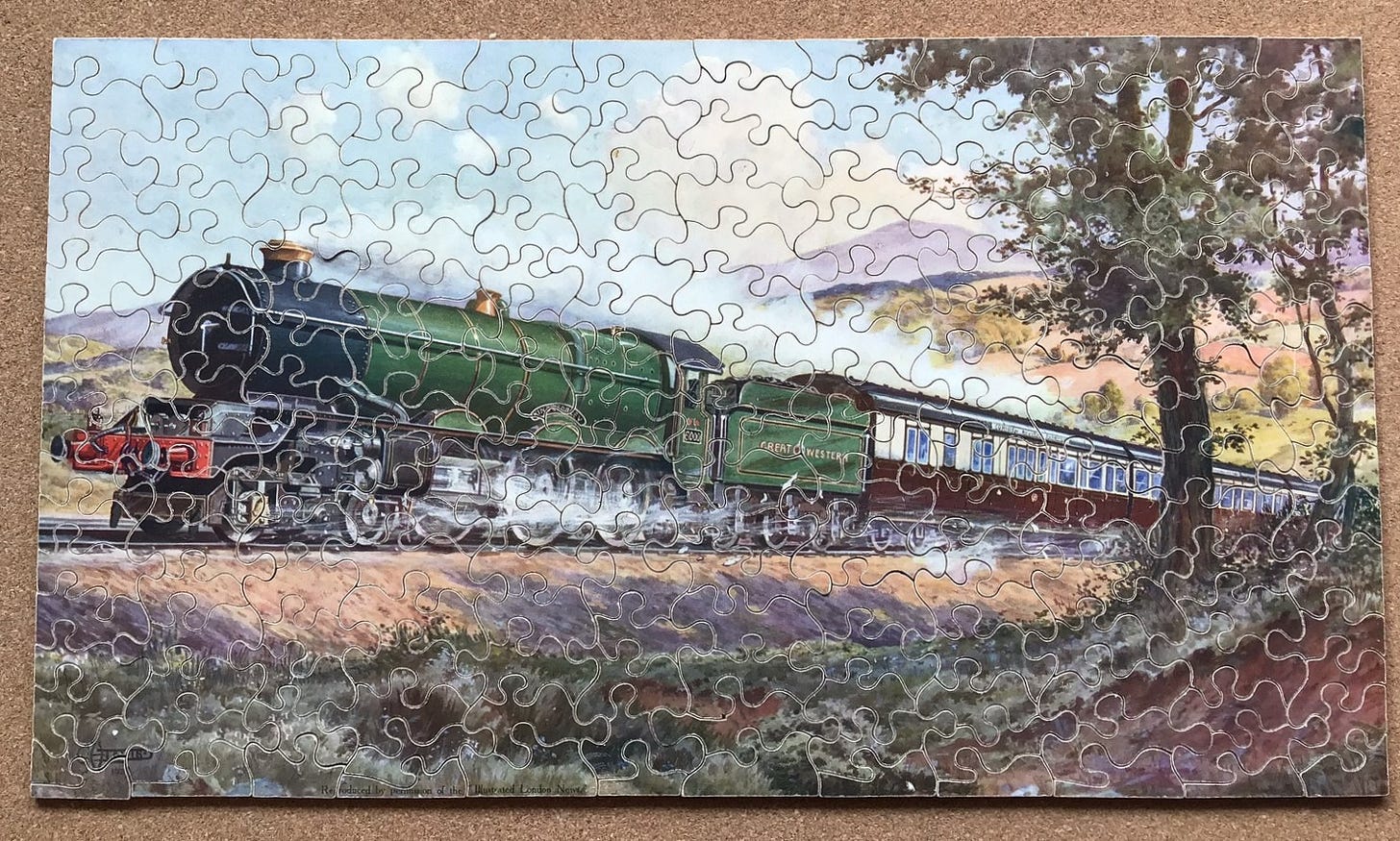

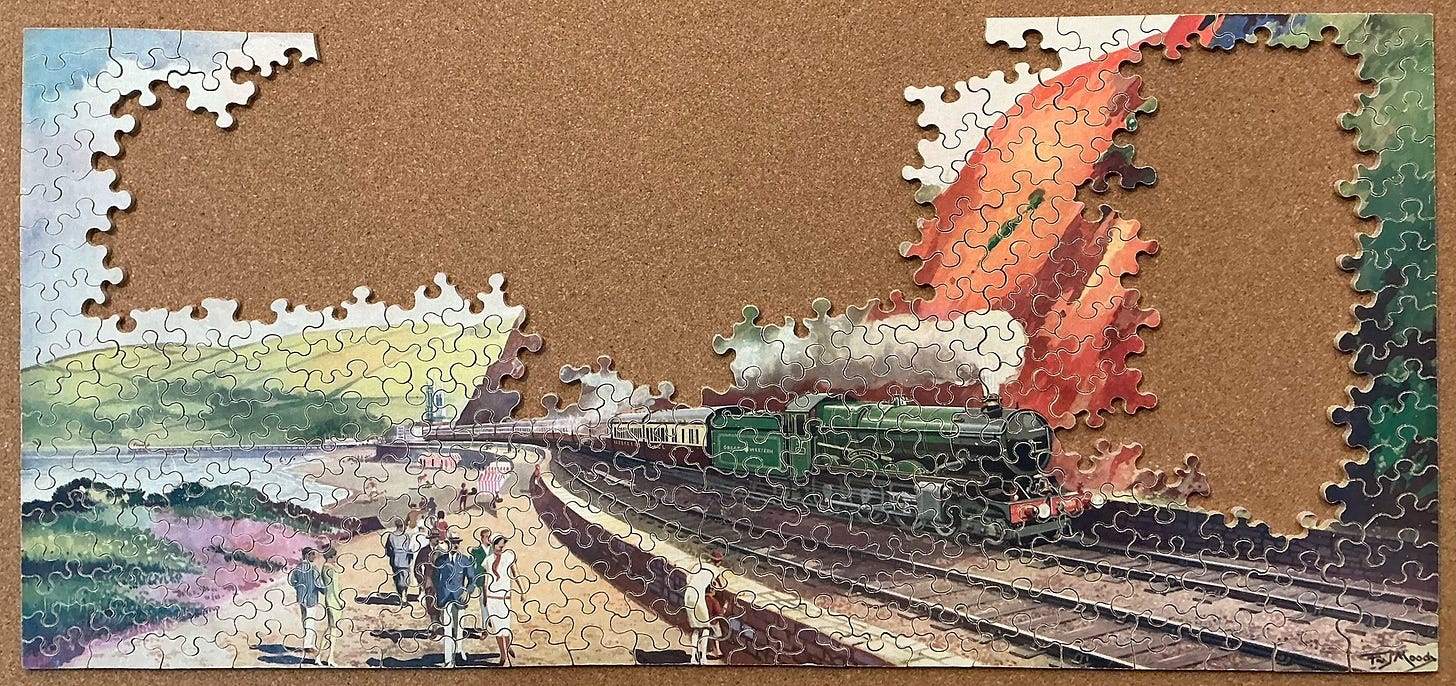

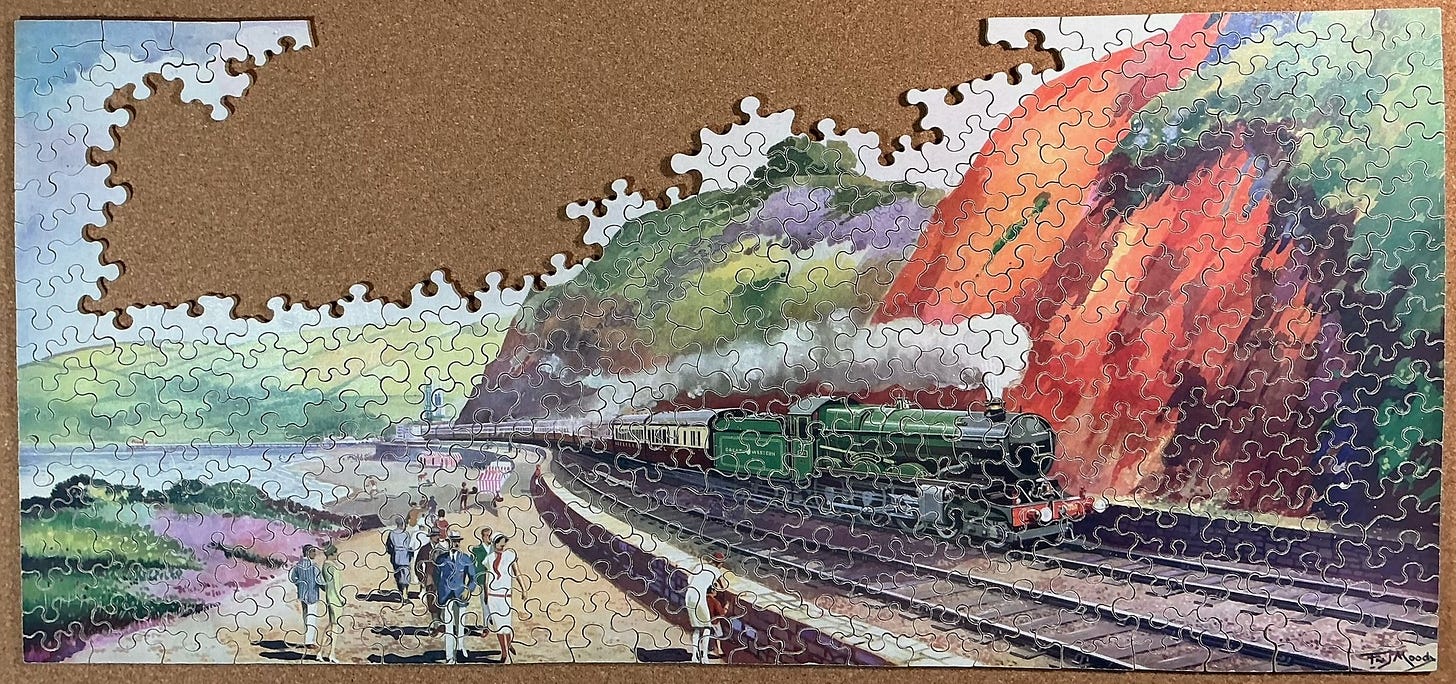

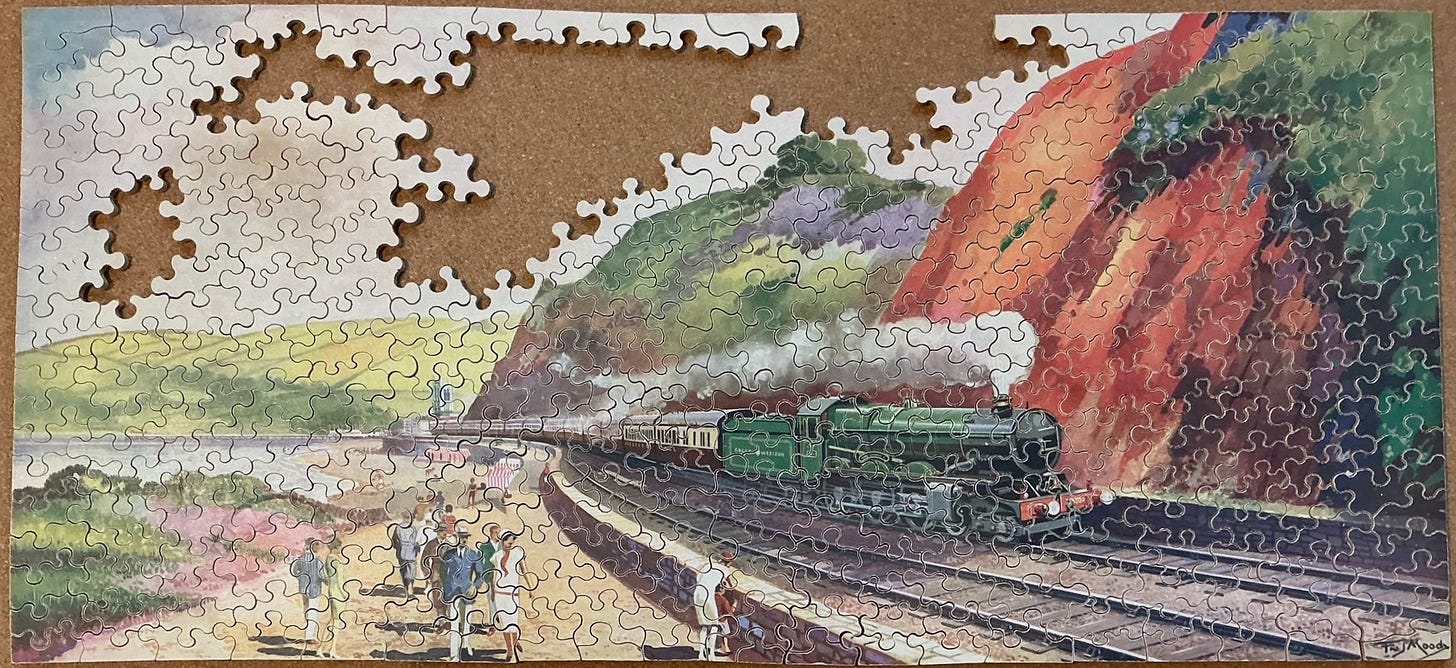

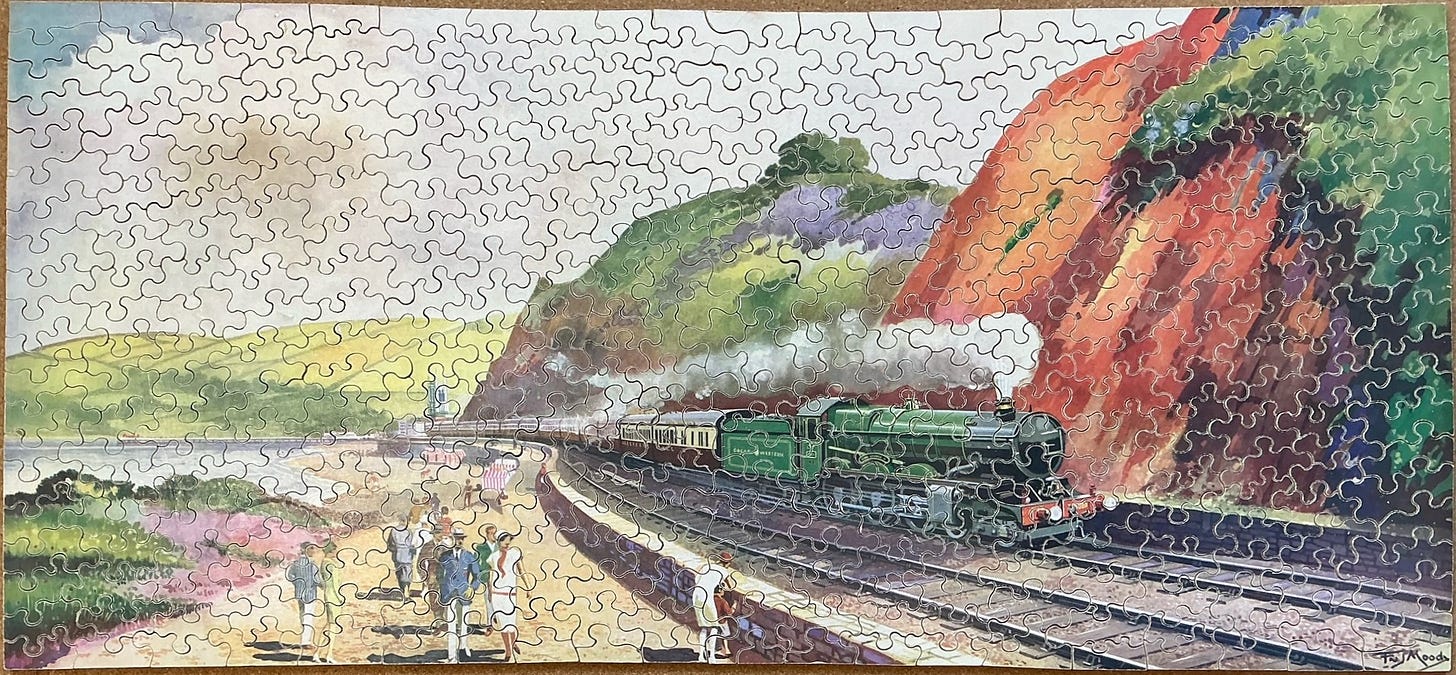

The Torbay Express made by the Chad Valley Works

maker – The Chad Valley Company for the Great Western Railway Company

date – ca. 1928

~375 pcs 12¼” x 26½” (31x67 cm) ave. 5.5 cm²/pc 4+mm 3ply

fully-interlocking “baroque” cutting; no figural pieces

image – commercial artist and illustrator F.N.J. Moody (1892-1975)

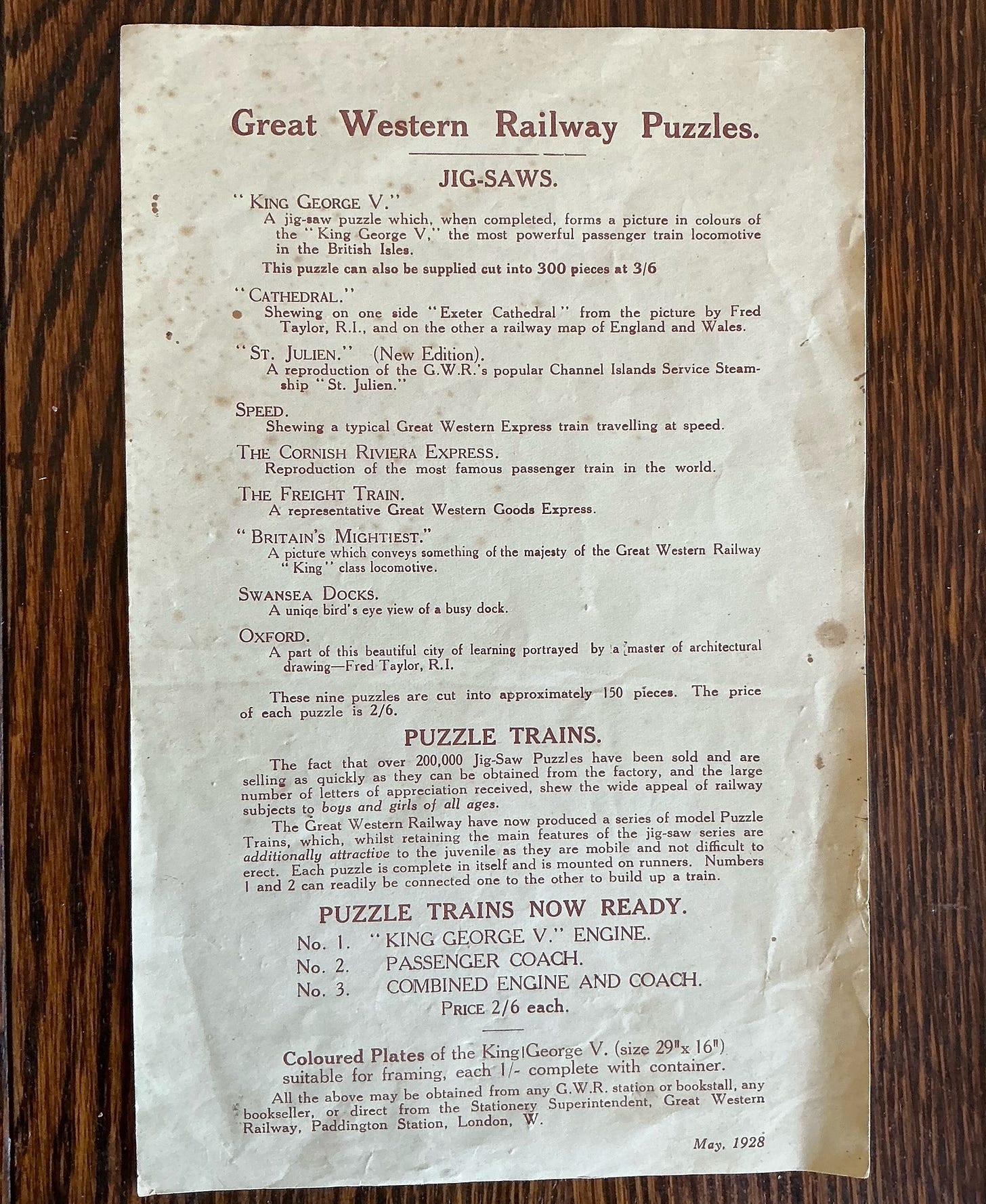

This puzzle was one of 44 puzzles that Chad Valley made especially for the Great Western Railway (GWR) from the mid-1920s to 1939. They were commissioned by the railway’s Publicity Department in conjunction with its Stationary & Printing Department. The GWR did not aim for puzzles to be directly profitable for them. It was a promotional campaign that cost them money because they sold the puzzles at considerably less than cost.

The idea was to make GWR puzzles for sale as souvenirs at the book, magazine and souvenir stands in or across from their stations, as well as wholesaling them to other vendors such as booksellers, toy shops and department stores. The scale of this promotional project was very large. Over the 14 years more than 10,000 copies of most of the 44 GWR puzzles, including this one, were made. The Torbay Express was one of the largest and most expensive puzzles in the series. It sold for 5/0 (five shillings.) Most GWR puzzles had only 150 pieces and cost 2/6.

The GWR’s puzzles did not have whimsies, which were becoming popular at the time, but had something else that made them very classy. The company they selected to make the puzzles as the Chad Valley Company. Chad Valley was a toymaker that was widely known for making high quality “toys for toffs” that most children could only wish for when they saw them in the toy stores but their parents could never afford.

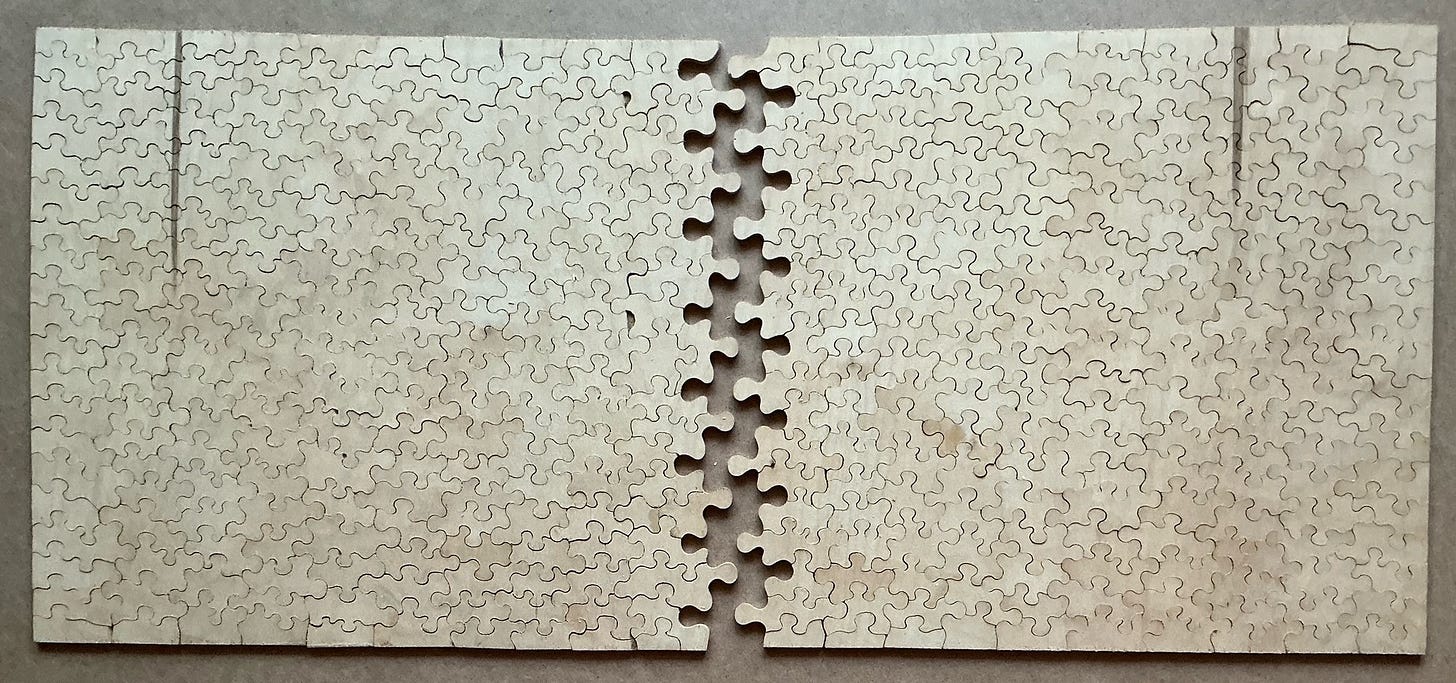

Chad Valley had only recently followed others in the toy industry by beginning to make jigsaw puzzles for adults, and their business model for this new line was a change for the company: They aimed to make toff-quality puzzles at middle-class prices. The company could never have been the “low bidder” to make puzzles for the GWR if they had put it out to bid. As I discussed earlier, other puzzle manufacturers used efficient cutting styles so their production costs were much lower.

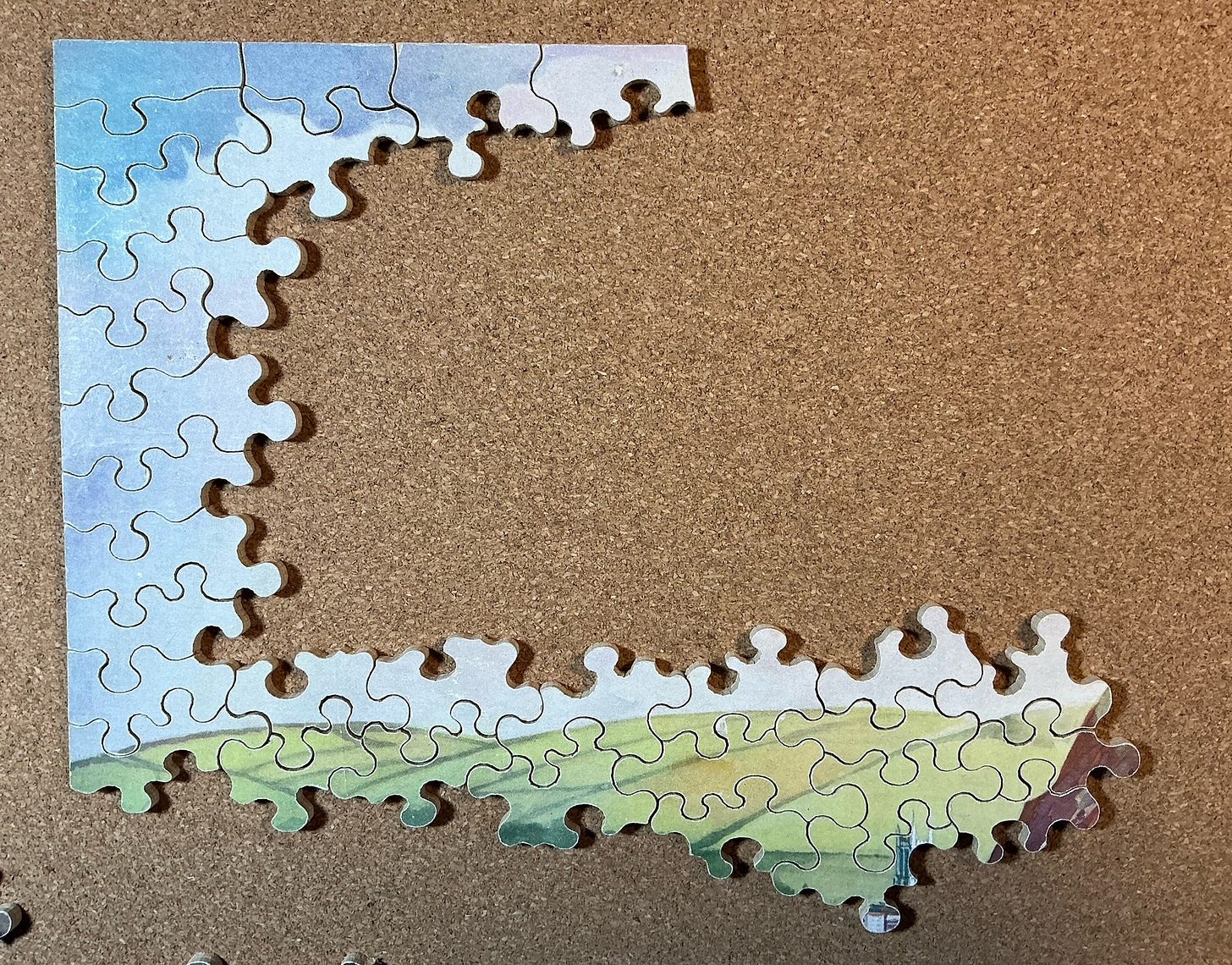

Chad Valley’s plan was to make and market high quality puzzles for the middle class, not the working class. Their house style cut puzzles that were that were both fully interlocking and had beautiful pieces (see photo below) but their style required that the cutting to be done slowly, one piece at a time. These shapes cannot be cut in strips. The Publicity Department clearly wanted puzzles for their promotional project that would convey the quality and classiness that they wanted the Great Western Railway to be known for.

Note that all of the connecting knobs and voids in the above photo are approximately the same size and rounded shape and that the rest of the cutting has similar curvature. There is no straight cutting; the cutter was constantly turning the blank while it was being fed into the sawblade. This makes assembly much more challenging. I love this “baroque” (my name for it) cutting style. Back during the 1930s jigsaw puzzle golden age it was commonly used only by Chad Valley and J. Salmon & Co. among the manufacturers, both of whom competed on the basis of high quality rather than competitive pricing.

Some of the GWR puzzles featured their celebrity engines which were famous during a time when the general public was fascinated by technological progress. The Torbay Express is such a puzzle. It shows the GWR’s premier locomotive the King George V, No. 6000, which as any schoolboy of the time would have known was more powerful than its contemporary rival the famous Flying Scotsman. In the puzzle it is seen heading east past Spray Point after having passed the seaside town of Teignmouth in Devon known for its historic Georgian buildings and long sandy beaches.

Basically, one could think of the images on all of the GWR puzzles as being advertising posters but their advertising message was extremely subtle. They didn’t have text and they often looked like fine art paintings. In puzzles with trains the company’s name only appears on the side of the engine’s tender, as it did in real life. In many of the GWR puzzles there is not even a train in sight: They featured historical events, landscapes and buildings associated with the famous tourist destinations to which the railway brought passengers. But the classy logo on the box holding the classy puzzle would remind assemblers of the only trains that they could take get to that classy location.

The GWR puzzles on offer varied during the 15 years in which they were made, as new ones were launched and old ones discontinued. This one was introduced in 1929 and was in production to 1934. Mine is in an early style box and inside it there is an advertising flysheet dated May 1928, so I think my puzzle is probably from the inaugural batch.

The GWR’s promotional puzzles proved to be a very effective marketing ploy that was soon copied by many other companies but rarely with the subtlety of messaging that GWR used. In fact, most do look exactly like advertising posters.

I have more information about the Chad Valley company and its ground-breaking collaboration with the GWR in my report about the Royal Route to the West. In fact, there is a lot of information available online about the GWR series because they are among the most collectable of all vintage puzzles. As David Shearer notes it is:

… surely one of the most interesting and researched series of puzzles, produced in Britain during the heyday of wooden jigsaw manufacture [in] the 1920's and 1930's. This series wonderfully demonstrates the advancements being made in both style and quality. They include early non-interlocking puzzles, experiments with double-sided puzzles, colour line-cutting, wavy edges and even twin puzzle sets. Many of these techniques were being used by other makers at a similar time, but it is fascinating to be able to see all these styles as well represented as they are here within Chad Valley's GWR promotional series.

The Chad Valley Company’s success with this series and with other promotional puzzles that followed it, and the collectability of all of them now, is sufficiently notable that there is even a whole book about the phenomenon; The Chad Valley Promotional Jigsaw Puzzles, written and published by Tom Tyler in 2017. (It is out-of-print. Please contact me if you have a copy that you are willing to sell!)

And separate from puzzle collectors, the GWR puzzles are also highly sought after by British railway buffs as memorabilia from the age of steam. Railway buffs seem to be much better than puzzle people at researching the history of their subjects of interest and posting their findings online. Here, for example, is a blog maintained by “David” that seems to treat finding jigsaw puzzles with images of steam trains to be a variation on the British hobby of trainspotting. From him I learned that “The first 'Torbay Express' ran in 1923 from Paddington to Torbay (Torquay) and by the mid 1930's the journey was taking 3.5hrs including a short break at Exeter and station stops at Paignton, Churston and Brixham. 'Castle' or 'King' class locomotives usually headed the express.”

I found this website for railway heritage people maintained by Colin and Daniel Taylor, who obviously have a huge collection of GWR artifacts and memorabilia, to be particularly interesting and useful for my research. But unfortunately neither they nor I could find any substantive information about F.N.J. Moody, the commercial artist who painted the image for The Torbay Express other than the dates of his birth and death, and the fact that he went by his first-name initials FNJ rather than by Frank, Norman or James.

Another reason for the GWR puzzles’ popularity among collectors may be that the images in the series were very good for puzzle assembly. I don’t know whether they were selected by someone at Chad Valley, or someone with the GWR, or a collaboration between them. But whoever did the choosing seems to have had a good eye for puzzlecraft.

Not all good paintings make for good puzzling. For example, a painting that must have been considered would be Rain, Steam and Speed in the collection of Great Britain’s National Gallery and on display at Tate Britain. It is an 1844 masterpiece featuring a GWR train by the master of light and loose brushwork J.M.W. Turner, who was a major influence on Claude Monet and the other impressionists. I encountered that painting many times while googling for my research.

Rain, Steam and Speed depicts one of the company’s very early trains, interpreted as a symbol of industrial advancement rushing towards us. Turner was one of the very few artists in the 19th century who considered technological progress to be worthy of being depicted in art. But the colour pallete in the famous Turner painting is so subtle and subdued that it would make for very challenging puzzle assembly, especially if the puzzle were cut in Chad Valley’s already challenging baroque style. I think it was a good call not to issue a puzzle with art’s most famous GWR image despite the fact that I very much like it as a painting.

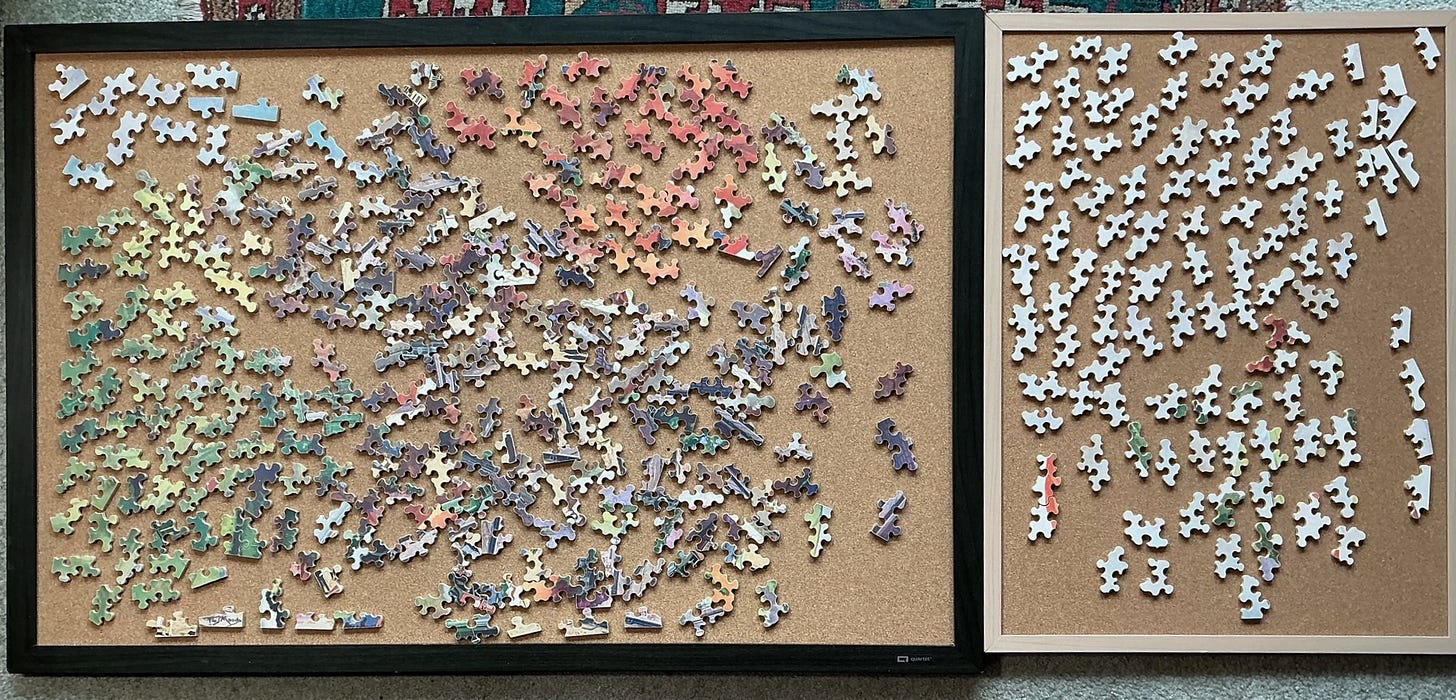

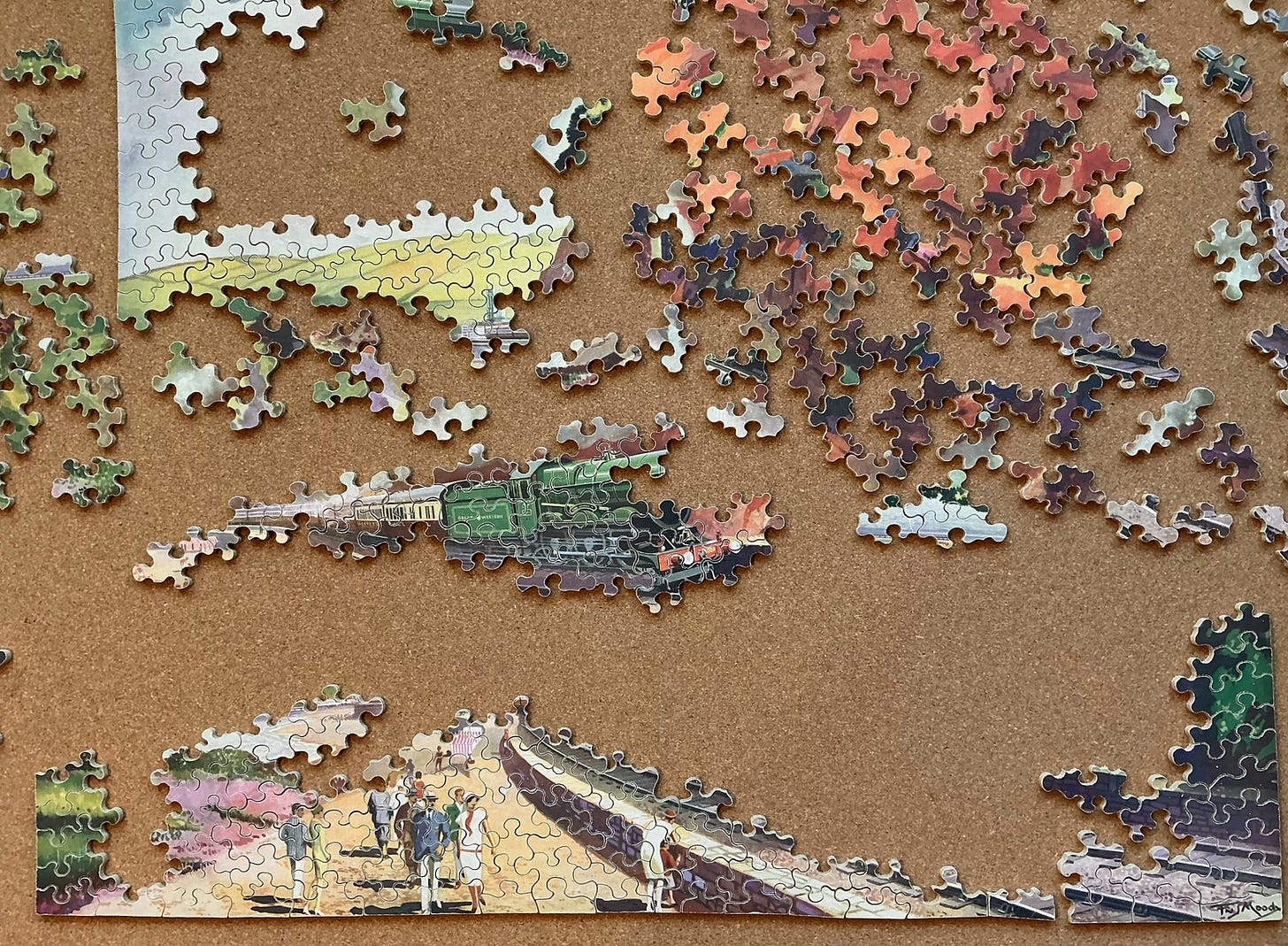

But back to The Torbay Express. This is another image about which I remembered very little other than that it was a train puzzle and I purposely avoided looking at the small b&w picture on the box cover before beginning my assembly. When I spilled its approximately 375 pieces onto my puzzle-board the first thing I noticed was that they were quite thick and large. There was a handwritten notation on the box cover saying that it would assemble to be 26½” x 12½” (63 x 31 cm). That’s pretty big so I spread the sorting onto two boards to ensure that I would have some working space. The very pale pieces (probably sky) seemed most numerous so I put those on the side-board:

I began with some easy wins in order to create more working space. On the side-board I connected the sky pieces that had some green, and on the main board I connected ones that had sky and some reddish-orange, and worked out from there on both sub-assemblies. In both cases that led into edges. I had not planned to do edges first, but there they were.

Assembling edge pieces first gets one off to a quick start but (as I have frequently mentioned) whenever possible I prefer to develop a puzzle image’s focus of attention first. In this case, what that would be was obvious from the puzzle’s name and most of the train pieces proved easy to recognize. Also, I found a number of pieces with people in them so I began to make sub-assemblies of those. I knew from my recent experience with the Nativity Play; 13th Century puzzle (reported on in the previous newsletter) that the varying sizes of the people would be very helpful in the placement of those pieces in the puzzle and that too led to some edge assembly.

I got stuck with the train but made good progress with the people, partly because they linked to edge pieces (which are very easy to recognize in puzzles with baroque cutting) …

… and then my main board looked like this:

I noticed that the lowest piece below the engine in the train subassembly had a khaki knob that would fit into a place in the bottom assembly. And after combining them I saw that the lowest piece in the top assembly was one of the train cars. That gave me this:

In general the pieces were in very good condition but there was one piece that had some serious visible damage. Looking at its back I could see that it had been repaired by someone because the middle layer of ply had deteriorated and the bottom one had broken. The paper had presumably gotten damaged during the repair.

I contributed to that anonymous person’s repair by using my coloured pencils to make this paper damage less noticeable. You can decide how successful I was by zooming in on the following photo. If it is hard to find I achieved my objective.

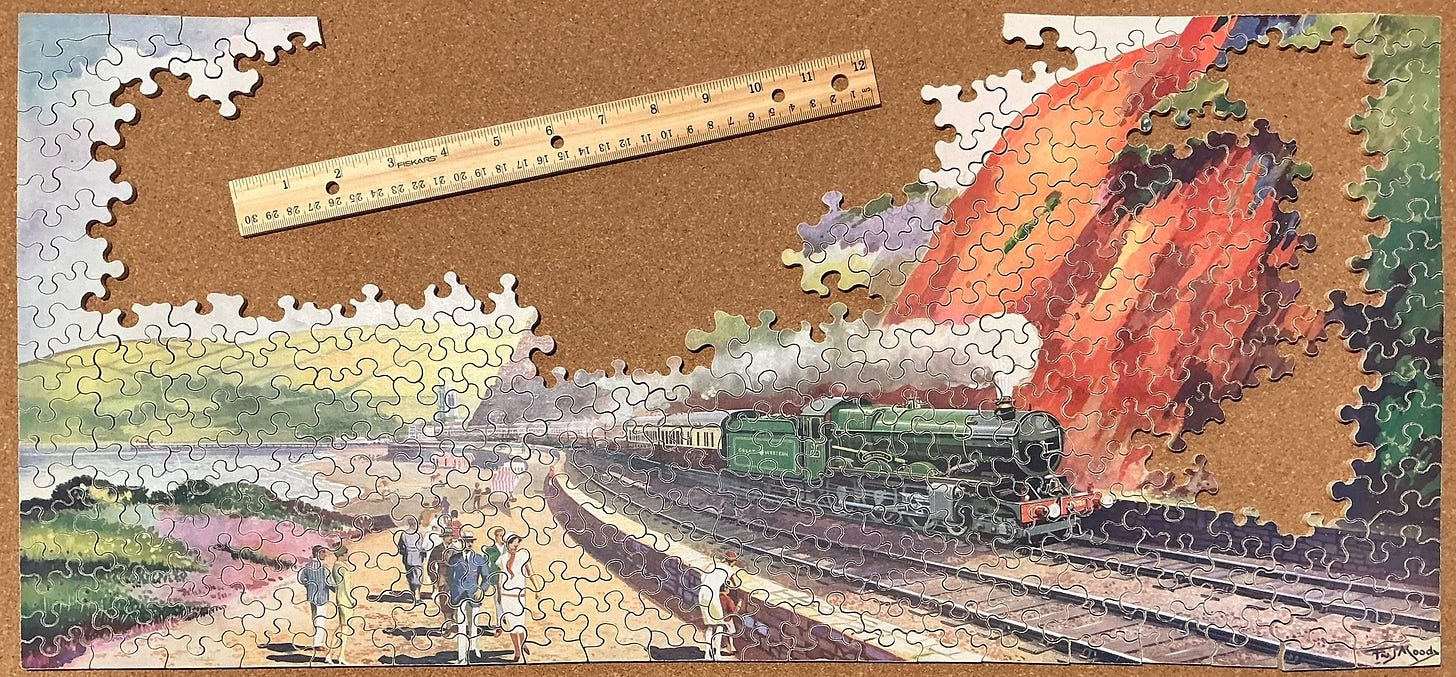

I said that this is a large puzzle. To help you understand what I mean I included my ruler in the next progress photo:

Before long I had used up almost all of the pieces that had colour in them:

Up until here all of my progress had been fairly rapid but that was largely because this image is filled with colour clues to help assembly. But I knew from experience that from here on this baroque cutting style would get very challenging. All of the loose pieces that I had left on my puzzle board now looked a lot like the baroque-cut ones that I had left with the only puzzle that I have not been able to complete to date.

But that one had perhaps 150 pieces remaining, and this one had only about 40-50 more to go, and I like to think that my puzzling skills have improved since then. Still, I knew it would be slow going from here on. I began with edge pieces and ones in which the clouds looked darker than the rest:

Slow going all right. 25 pieces left, but now with no colour clues at all:

Still slow going but it never felt like frustration because I could see that every placement was getting me closer to success. Eleven left:

What a beautiful puzzle!

While I was assembling it I sometimes wondered how such a long puzzle could have been cut on a scroll saw. Baroque cutting requires turning the blank around a lot and the size of blank that a cutter can manoeuvre is limited by the “throat” of the scroll saw – the distance from the blade to the vertical upright at the back of the saw that supports the top arm. At some point in assembly, about where the picture with the ruler was, I noticed that there was a continuous vertical cut-line down the middle of the puzzle in which the knobs were at least double the size of all of the other ones in the puzzle (which were pretty uniform in size) dividing the long blank into two with more manageable sizes.

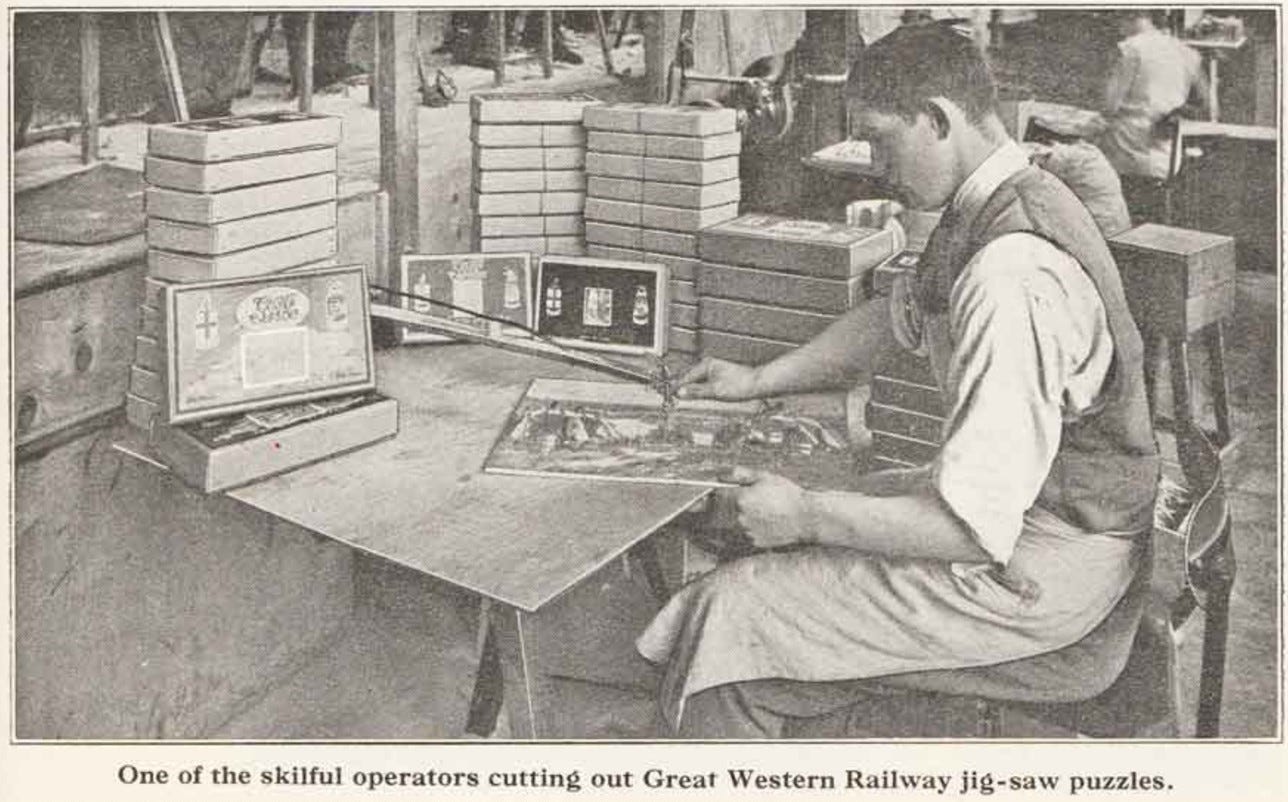

I thought that Chad Valley must have had one saw with an extra deep throat and that someone (possibly someone other than the puzzle’s piece-work cutter) may have used it to make that continuous cut. While doing my post-assembly research I found this photo of a Chad Valley cutter who might be working at such a saw but I have suspicions about it.

The photo is obviously posed, otherwise why would a cutter be surrounded by boxes? And is that really a working scroll saw? It does have incredibly deep throat but also an incredibly thin upper arm. It has no treadle mechanism; electric-powered saws were available by that time but there is no cord to a foot pedal like electric sewing machines have. Its huge work surface is only a flimsy thin sheet of plywood resting on a sawhorse. On the other hand, the factory would have needed only one such saw with an extra-deep throat for only occasional use, so this might be it.

Coming up

I have been on a vintage puzzle binge since mid-April. Almost all of the puzzles that I have assembled since then have been vintage ones (although some of them have been “vintage” whimsy-filled Wentworths that were made only 20 years ago.) It is not that I prefer vintage puzzles to newly-made ones, although assembling them does appeal to the heritage conservationist in me and they do have their own je ne sai qua charms. But our current craftspeople, laser-cut designers and cutters alike, “stand on the shoulders of giants” and produce inventive and entertaining designs, and modern printing is definitely superior to what could be done 50 or more years ago.

As I said in the introduction to Part 1 in this two-parter, I began buying vintage hand-cut factory-made puzzles as part of my search for “frugal alternatives” to premium quality new puzzles. That is why most of the vintage puzzles I have bought to try them out have been relatively small: As with new puzzles their price is roughly proportional to their size and this has been an exploration to see whether or not i like vintage puzzles, and which styles and brands I prefer.

I have now done enough of them to conclude that high quality vintage ones are indeed a better frugal option for me and my personal trade-offs than inexpensive thin new puzzles, especially the 3mm ones that are made by the vast laser-cutting puzzle factories in China. So I have been on a bit of a vintage puzzle buying binge lately and have gotten brave enough to successfully bid for larger ones.

My initial plan had been to alternate frugal ones with premium ones and I have been continuing to buy those too, so this recent binge with frugal ones has meant that I have accumulated a stash of very promising contemporary puzzles and I will now binge on those for a while. But first my next few postings will continue to report on vintage ones that I have already assembled but have not yet written about. These include some whimsy-filled vintage Victory puzzles, and postings about ones made by the British hand-cutter Enid Stocken and her descendants who still make them in a vintage style under their Puzzleplex brand.

Thank you, Bill, for putting so much effort, including research, into what you have to share. I’m going to try to respond to today’s posting in just about 200 words. We’ll see how close I come to doing that. I’ll list my responses in point form:

1. It was fun to see “don’t Make a Noise” analyzed and to notice that my wife rated a photo credit. She and I recently completed that puzzled, borrowed from yourself.

2. I find that the way you displayed “An Old Persian Love Lyric” was very illustrative of points you made about cutting.

3. I got a kick out of the account of the Joseph K. Straus Company’s atypical labelling, with some extended “storytelling” and the curious “stamp” regarding use of a photo.

4. The soft-focus photo of the Inuit trader’s teenaged daughter is a treat!

5. The Chad Valley box, featuring a lovely blue field, a Canadian mountain-railway inset, and what look like coat-of-arms elements is super cool!

6. The Picture for the “Rain, Steam, and Speed” puzzle is interesting to me as a painting, but less appealing to me as a jigsaw puzzle image—too misty and vague.

7. The image of the Great Western puzzle maker at work is old-timey and evocative.

Cheers,

Greg