13. The history of Victory jigsaw puzzles

An essay about G.J. Hayter & Co. Ltd, the company that made the “Victory” brand of jigsaw puzzles (about 7000 words; 21 photos)

Instead of a puzzle review and assembly walk-through accompanied by an essay about a related topic, this posting is just an essay. But it is a rather special one. Please note that it is primarily about jigsaw puzzles made for adults and includes generalizations that do not necessarily apply to the manufacture of jigsaw puzzles for children, either by Hayter or by other companies.

Information that I have found online about G.J. Hayter & Company who made the Victory brand of puzzles is scanty, and much of the online information (especially in its Wikipedia entry) is incorrect. Much of the content here comes from the late Tom Tyler’s 1997 book British Jigsaw Puzzles of the 20th Century. That book is now out-of-print but new copies are still available from the publisher (for only £4!), from Amazon, and elsewhere.

I anticipate that I will continue to get further information about Gerald Hayter and the Victory line of puzzles in the future, and as I do I will update this essay.

[Note: Henrik Hjort, a Swedish collector, has recently posted a very useful website about the gold-boxed Victory puzzles that includes a guide for getting a an approximate dating of when they were made based on their packaging and end labels. You can check it out here. Based on that, and a copy of Brian Price’s monograph about the history of G.J. Hayter & Company, I am currently in the process of updating this essay. My text currently incorporates some of the new information. I’m currently busy with other stuff but I should have this process completed within a few weeks.]

Introduction about buying vintage British puzzles

Not too long after I became interested in wooden jigsaw puzzles I began to search for frugal alternatives to expensive new hand-cut puzzles and premium-quality laser-cut ones. (I am not complaining about the price of premium puzzles. I know that they are labour-intensive to make and require pricy materials and I still buy them as well as less-expensive alternatives.)

Among of my favourite “frugal alternatives” have been has been vintage factory-made hand-cut puzzles, especially the vintage hand-cut Victory brand ones that were made by G.J. Hayter & Company, as well as used laser-cut puzzles made by Wentworth Wooden Puzzles. I mainly get them from British eBay auctions. As I discussed in my essay about British jigsaw puzzle history in this posting, a lot of wooden jigsaw puzzles for adults were made in the first half of the 20th century before the general public was attracted to less expensive cardboard ones. Several of these vintage puzzles come up at auction every week there on eBay, and they often sell for very reasonable prices. Also, shipping costs from Britain are much lower than from the US [Note: To get the best deal, buy several puzzles from a dealer who will combine them into one mailed shipment. The Royal Mail shipping cost/puzzle is most cost-effective for a 4-5 kilo parcel.]

Among the most frequent vintage puzzles to be offered for sale in Britain are ones branded “Victory” that were made by G.J. Hayter & Company. As you will read below, after the company’s early beginnings they them were made by workers in a factory (rather than by cutters in an artisan workshop) and the cutters used efficient cutting designs. They were among the less expensive hand-cut wood puzzles from the 1930s to the 1980s and sold very well back then.

Now, their abundance makes them less attractive to the high-bidding collectors of vintage jigsaw puzzles, so old Victory brand puzzles are also among the less expensive ones today. They they are a good deal for people whose interest is assembly rather than collection, as well as people who want to have a more frugal specialty collection. From an assembly point of view, with their thick pieces, vintage images, and hand-cutting they are attractive and fun puzzles for us to build today. Even the patina that comes from wear over the years adds rather than detracts from their appeal.

The early years

G.J. Hayter & Company, based in Bournemouth, on the south coast of England, made the Victory brand jigsaw puzzles. It was the only major puzzle-making company that was founded by a puzzle-maker rather than being one of many products made by a printer or toy-making company. The Hayter company stayed active manufacturing hand-cut wood puzzles long after all the other factory companies had ceased production because of the growing popularity of the much-less-expensive die cut cardboard puzzles. It undoubtedly made more hand-cut jigsaw puzzles than anyone else in the world. This is its story.

Gerald Hayter was born in 1901, the son of a Dorset farming family. His interest in jigsaw puzzles was sparked at the age of eight when he was given a 100 piece one (an oval shaped portrait of a political candidate) as a child. Jigsaw puzzles had been invented about 150 years before that, but for about 100 years they were only made as expensive educational toys for the children in well-off families, with pictures such as maps or stories with morally uplifting themes. Frankly, they were rather boring: Remaining puzzles from that era are often in very good condition because they were rarely re-assembled. But about 30 years earlier, with less didactic images, jigsaw puzzles slowly began to become a recreational activity for adults as well as children, and in 1908 a huge upper- and middle-class jigsaw puzzle craze had swept through North America, Europe and Britain.

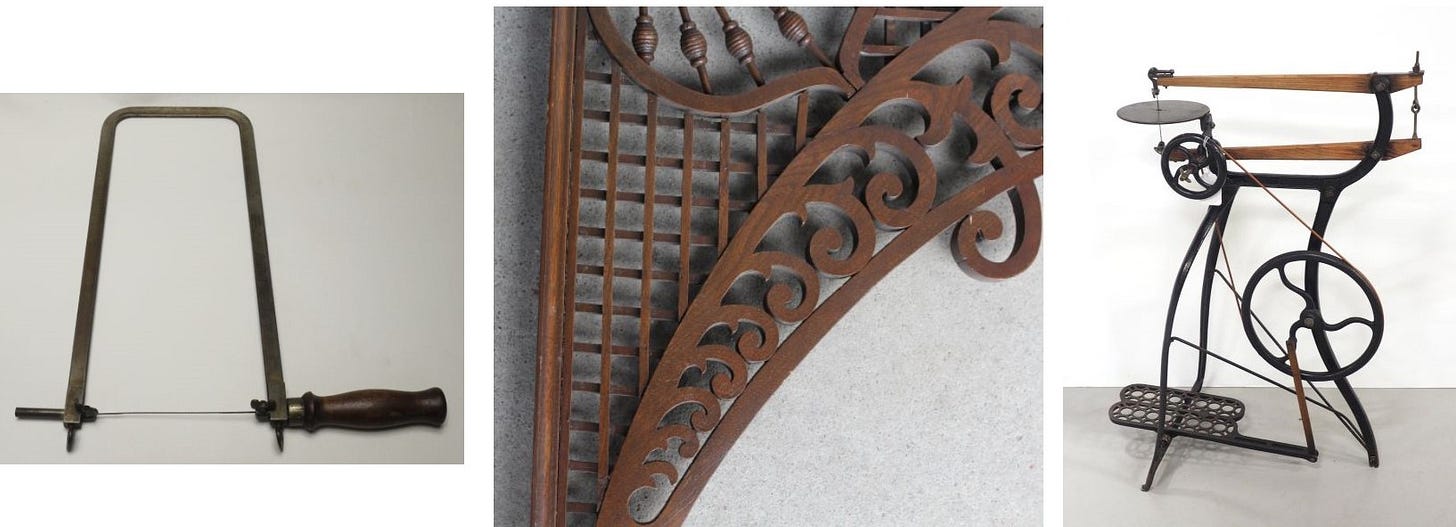

Gerald’s first puzzle became one of his most prized possessions. The following year his parents bought him a hand-held fret saw so that he could make jigsaw puzzles for himself. Before long he was also making them as gifts for relatives and friends. Two years later he upgraded to a treadle-powered scroll saw.

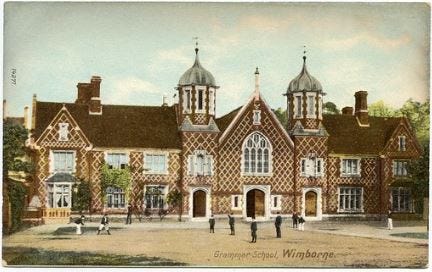

The evolution of this from being a hobby to becoming a part-time business would have taken the familiar pattern of an amateur cutter giving them as gifts to family and friends, and then evolving either through word-of-mouth reputation or self-promotion into becoming a professional puzzle maker. But progress on that path was slowed down by his young age and a very fortuitous development: In 1912 he won a scholarship to attend the nearby private Wimborne Grammar School (which had been founded in the 15th century.)

At that time the school (which is now known as the Queen Elizabeth’s School) had about 30 boarders and Gerald would have been one of the equivalent number of “day boys.” With his studies and homework, time needed for travelling to school and back, and doing his share of work on the family farm, young Gerald did not have much time for his hobby during those years. Even so, in 1914, at the age of 13, he made his first professional puzzle. It took about two weeks of his spare time to make a double-sided puzzle for a company called Toysinit, for which he was paid 7/6d (the equivalent of about £30 today.)

Hayter graduated from Wimborne in 1917. England was embroiled in the Great War war, but there were indications that the trench stalemate would soon be broken: The naval blockade of Germany was starting to show evidence of success, and America had entered the conflict on the Allies’ side. The war wouldn’t be over for another two more years but England could see the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel. In any event, at the age of 16 Gerald was too young to enlist.

We don’t know if he ever considered higher education, but it is obvious that the talented and ambitions sixteen year-old decided that a lifetime of farming was not in his future. I suspect it was because of the wartime staffing shortage that enabled the young farm-boy to get hired for £1/week as a junior bank clerk in Christchurch, in the suburbs of Bournemouth. That required setting out on his own and moving from the farm to the city.

Young Gerald brought his scroll saw came with him to supplement his meagre initial bank salary. He invested in adapting it to be powered by a motor and set up a small workshop in a small shed on a neighbour’s property. At first his puzzles would have been in the old push-fit style, but Hayter not only he kept up with other puzzle-makers when the interlocking style of cutting became much more popular he became a leader in figuring out how to cut them with maximum efficiency (see my analysis of that here.) Before long he had an open order to supply his puzzles to a London shop.

In the early days the images on his puzzles were frequently made from unsold calendars, which had well-printed colour images on good quality paper. Gerald became good friends with the owner and proprietor of Beales, the largest department store in Bournemouth. Beales would have sold Hayter’s puzzles and may have been one of his early sources of unsold calendars. Later, after the company expanded and larger quantities were needed, he obtained good quality colour prints by the gross from printers.

Typical subject matter for the images on jigsaw puzzles from all makers at that time were, and remained, country scenes and nostalgic genre paintings of rural life, fox hunting, gardens, seascapes, interior scenes with people in period dress, and maps. According to Brian Price: “It may be suggested that there was a certain gentility implied in the subjects of jig-saw puzzles, most things modern being ignored.”

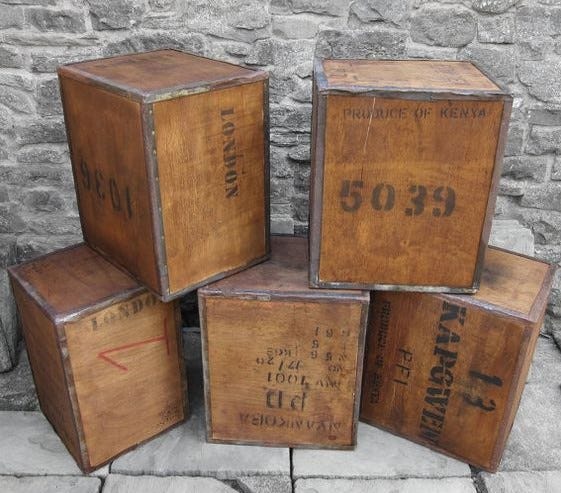

Initially his wood was recycled from tea shipping crates but he would have recognized that an important element in the quality of a finished jigsaw puzzle is based on the quality of the wood itself. A new material was becoming available and affordable – plywood. It was much better for his purposes than the warp-prone thin sheets of wood that came from used tea crates. I am sure that assessing which type of plywood was most suitable (he chose beechwood) and lining up a reliable source of supply for 3-, 4- and -5ply wood were important priorities in implementing Hayter’s business plan.

Soon his side-gig was bringing him more income than his bank salary despite the fact that much of his “free time” involved participating in training programs from the Chartered Bankers Institute in order to pass its various certification examinations. He began a pattern of having a six day work-week that did not end until about 10:00 in the evening. After 1924, outside of his “banker’s hours” this was side-by-side with his new bride Nellie who also became his apprentice and business manager.

By the latter 1920s Hayter clearly had ambitions to grow his puzzle-making business beyond being a small family workshop. It is not clear when his company first began using the brand name The Victory, which later evolved to be just Victory, but I suspect that it goes back to about the time of the Armistice in November 1918. In 1927 he trademarked both names and incorporated his business as G.J. Hayter and Company.

Even before that time he had been expanding by getting orders from more stores and hiring and training more workers. Cutting was the job that required the most training and in keeping with the custom of the time that job was only done by men. They were paid piece-work by the puzzle so their take-home pay increased as their skills and speed increased. Other roles, such as gluing the printed pictures onto the plywood, sanding and inspecting the cut puzzle pieces, and making and labeling the boxes, and packing, shipping, etc. were less remunerative and were done by both men and women. I don’t know if some of that work was also paid on a piece-work basis.

As the company grew they had to relocate a couple of times to have adequate work space, first from multiple garden sheds to a rented loft above a coach builder’s workshop, and then to a small factory space near Bournemouth’s Central train station. Still, Gerald kept his day-job. His wife Nellie supervised production during the daytime when he was at the bank but the business was growing rapidly making high-quality puzzles. The Hayter company diversified, making children’s puzzles and other plywood educational toys for children, all branded under the Victory name.

Sometime along the way Hayter had a setback that could have doomed the fledgling company. Just as jigsaw puzzles had suddenly become a middle class craze in 1908, table tennis (AKA ping-pong) filtered down from being exclusively upper class leisure activity to becoming a popular middle-class craze in England in the mid 1920s. Hayter wanted to jump on the bandwagon. He used his growing understanding of how to fabricate with plywood and his reliable source of supply for that material, as well as his knack for designing attractive packaging, to diversify into also making table tennis sets.

He devoted a lot of time, and invested hundreds of pounds, into preparing a large order for one purchaser. Then the purchaser fell into severe financial difficulties and could not pay! Fortunately Hayter was able to eventually collect most of his money but he learned valuable business lessons from that near disaster.

Unlike almost all of his contemporaries, Hayter did not sell directly to the general public nor to businesses through a wholesaler. A 1928 advertising pamphlet listed about 150 puzzle images and had puzzles in sizes from 50 to 1000 pieces. The pamphlet was aimed at department stores and other retailers and touted both the sales appeal of his puzzles in their attractive packaging, and the savings that merchants would have by buying directly from the factory.

I don’t know what his earlier packaging looked like by by 1928 it was a hinge-topped box clad in wallpaper, and following the common practice at that time images of the completed puzzle were not put on the box. Instead it had a generic image of friends assembling a puzzle:

The puzzles’ cutting also reflected the rapidly-developing puzzle cutting trends of that time: Push-fit had been replaced by fully interlocking connectors, and since the company aimed to compete on the basis of quality not lowest price, the puzzles included the popular figural pieces (also known as whimsies or silhouettes.) See here for my detailed analysis of Hayter’s cutting style during the latter part of the 1920s.

The descriptions of the puzzles in the 1928 pamphlet, and the quoted prices as well as the image on the box-top, suggest at that time Victory products were targeted to middle-class customers. All of the puzzles were still typical English calendar fare – traditional and often genteel country scenes, hunting, gardens, seascapes, and interiors with people in period dress.

Throughout the 1920s, although the family-run company was growing rapidly and had become incorporated as a limited company, and was run with complete professionalism, I tend to envision the scale of G.J. Hayter and Company as still being more like a thriving craft workshop than as a full scale factory.

At that time I suspect that Hayter’s career objective probably still focused on rising in the world of banking despite the fact that his side-line was the more lucrative of his two jobs. Certainly, in class-conscious England his status as a banker would have been more prestigious than his being a successful craftsperson. I suspect his parents took more more pride in telling people that their farm-raised son was a banker than telling them that he had his own toy-making workshop in Bournemouth.

Growth during the Great Depression

By 1930, business was booming. The company needed to expand from their crowded downtown workspace, and also, Gerald saw an opportunity for a new business strategy. The Great Depression was just beginning but Gerald (and, I hope, his wife) were confident about the future of their puzzle business. In 1931 the 28 year-old Hayter quit his job at the bank to run the company full-time, and they purchased an empty industrial building in the nearby suburb of Boscombe on the opposite side of town. (It must have been a very large building because the company continued to operate out of the same location until its very end.)

The timing of their further expansion was certainly good. As the Great Depression began a craze for jigsaw puzzles was just beginning. Rising unemployment (or fear of it being ahead) caused belt-tightening and a change in people’s recreational tastes. Except for the growth of inexpensive cinema many people replaced evenings out on the town with evenings at home with friends and family.

It certainly didn’t hurt that everyone knew that jigsaw puzzles were among the favourite forms of recreation for the Royal Family and other members of the upper crust. And people found that they were also made good complement to listening to the radio. (That state-of-the-art entertainment had just recently become much more affordable, at least for those who still had jobs. Radios now had speakers instead of headphones that had to be passed around, and there were more broadcasters and programming diversity.)

The transition to being a puzzle factory during the dirty thirties rather than a craftsman workshop during the roaring twenties brought another big change that is a testament to Gerald Hayter’s business acumen. The company made an abrupt shift from making highest quality puzzles to offering product lines that were efficiently cut and inexpensively priced. More about that later.

As the 1930s progressed, G.J. Hayter & Co. expanded its distribution to include other countries in the Commonwealth as well as in Europe and North America. They grew to become one of the largest wooden puzzle manufacturers in the world. I have read various estimates of how many employees the company had at its peak, ranging up to 400 but I suspect that at least 200 is a pretty good approximation.

By the mid-1930s the “Jigsaw Craze” was already beginning to fade as peoples recreational and entertainment interests evolved and people turned to newly-invented board games like Scrabble and Monopoly. But demand for Hayter’s puzzles was less affected than some of its smaller and less efficient competitors: They had become the indisputable industry leader.

Victory series during the Jigsaw Craze

In 1932, now working out of his new factory, Hayter reorganized his offerings into several series reflecting different subject matter and differing price-points, and he introduced new packaging. All of his puzzles were still under the Victory brand name however their packaging now reflected their place in the company’s hierarchy of quality and price. Like all puzzle companies, Hayter distinguished between puzzles made for children and those intended for adults. Adult puzzles ranged in size from a mere 30 pieces up to 2000, but with 100-300 being the most popular sizes. Although the company did accept commissions most of the Victory puzzles continued to be sold through department stores and other merchants.

In response to the rapidly growing demand for adult puzzles from the working classes and unemployed people Hayter made inexpensive puzzles called the Popular Series. They had traditional nostalgic English images. Following the example of successes by other companies he also established the Topical Series that were similarly priced but featured more contemporary subjects like modern trains, aircraft and ships. There was also a variety of other lower priced topic-specific series, such as Cathedrals, Old Prints (fine art), and the Royal Family.

The puzzles in these lower priced series were fully interlocking and made from 4mm thick plywood. They did not have figural pieces which would have significantly added to the time needed to cut them and therefore to their cost. Instead they had a very efficient strip-grid cutting style (that Gerald Hayter may have invented.) Each piece had four sides, so the interlocking pieces in these series look similar to what most die-cut cardboard puzzles look like today.

As anyone who has assembled a cardboard puzzle knows, such puzzles can still be challenging but the degree of difficulty is largely due to the size of the puzzle and characteristics of the puzzle’s image rather than any trickiness in its cutting pattern. I suppose that it was in response to market demand (or perhaps a low opinion of the working class?) that these less expensive puzzles included a reference picture on the box cover, unlike the company’s more expensive puzzles for adults.

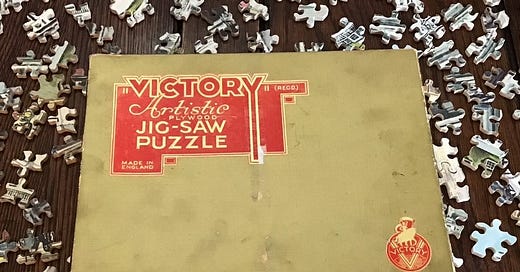

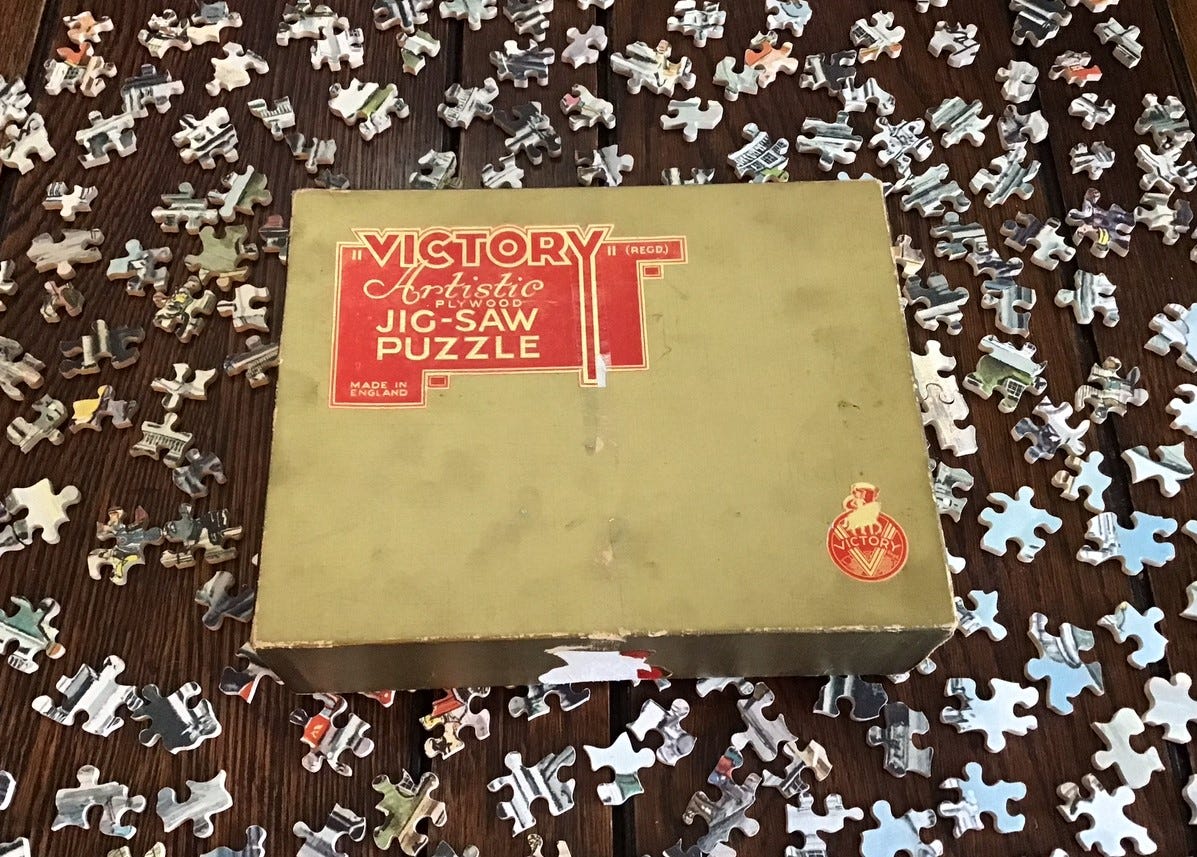

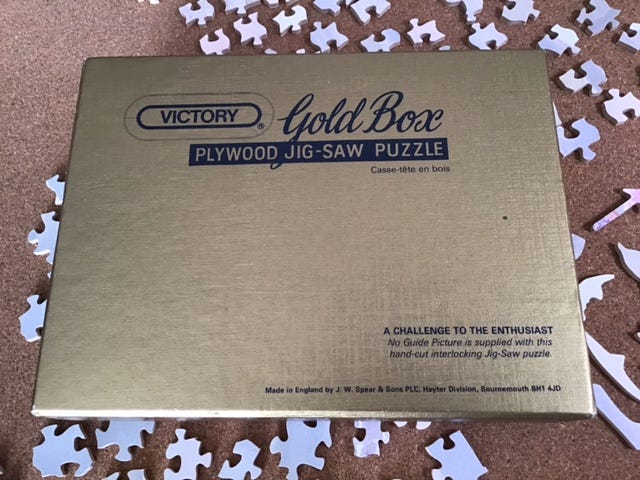

The company also made higher priced puzzles that included figural pieces. They were called the Artistic series and people instantly recognized them as such because they were packaged in a distinctive sturdier gold box. Well, at least they were more distinctive when Hayter first began packaging them that way! They quickly became very popular and people began to call them “Gold Box” puzzles rather than Artistics. While Hayter had been able to trademark the name Victory he could not trademark the colour gold for their packaging. Soon other manufacturers were packaging their own higher-tier puzzles the same way and calling theirs “Gold Box.” (Until much later Victory puzzles were never referred to as “Gold Box” on their packaging.)

Hayter’s gold-boxed Artistic puzzles stayed with the longstanding tradition for adult puzzles of not including a reference image on the box. In later years they featured that absence as being an advantage that added to the puzzles’ appeal:

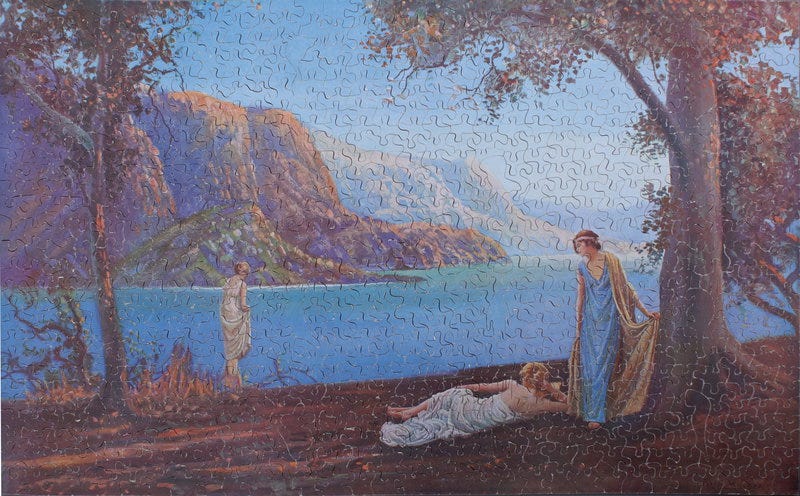

The Victory Artistic Series puzzles were made from full quarter inch thick (6mm) plywood. The cutting design usually was still mainly an interconnected grid pattern but in the Artistic series the four-sided pieces were interspersed with rather rudimentary whimsies. The puzzles were released in various sizes and their prices were proportionate to their completed size and number of pieces. Their images included a wide variety of subject matter although the styles of the images were all intended to appeal to mainstream tastes.

The company’s 54-page 1938/39 catalogue Hayter introduced a new more expensive higher tier of puzzles that it called its Super-Cut series, which were also packaged in the prestigious gold boxes. This series aimed to challenge not just their manufacturing factory-puzzle competitors but also the independent craftspeople who made bespoke puzzles for wealthy customers.

According to David Shearer, a major British collector who maintains the The Jigasaurus website (where most of these puzzle photos come from), the process for customers to buy Super-Cuts is uncertain. Only a few things are certain: Super-Cut puzzles were the most sophisticated puzzles that Hayter’s company ever made and compared to its other series the company did not sell very many of them.

Now this is just speculation on my part but it is possible that they were being sold before 1938. Hayter had a lot of customers for his very well-cut and more-expensive puzzles before he built his factory in Boscombe and trained up a lot of new cutters. I can’t imagine that during the depths of the Great Depression he stopped making puzzles for his established clientele from the craftsman workshop era, but at the same time his best cutters were probably busy training up the new hires. He might have had them continuing to make high end puzzles for those customers as special orders, and called them Super-Cut, but not listed them in his catalog which was aimed at merchants. Perhaps it wasn’t until 1938/39, when demand for jigsaw puzzles was slackening (because board games like Scrabble and Monopoly were the new craze) that he was ready to promote the slow- and difficult-to-cut high-end puzzles.

Super-Cuts required creativity from the cutter as well as a higher level of cutting skill. Their cutting designs interacted with the puzzle’s image and used other sophisticated cutting tricks. Besides having standard features like “random cutting” rather than a grid pattern, they included “colour-line cutting” - cutting along the lines separating two different colours or textures to make assembly more difficult. Other premium touches were particularly attractive and well-placed whimsies.

One distinguishing feature of all Super Cut puzzles was that rather than straight outside edges they had wavy edges (that some Super Cut aficionados call “pie crust.”)

The war years

It seems odd, but while the Great Depression ushered in good times for hand-cut wooden puzzles, the onset of the second World War marked the beginning of the end for almost all of the factories that made them. The war impinged on both family and social life, and demand subsided due to people entering the military or assuming war-related volunteer roles, while others worked long overtime hours in wartime industries.

Also, the skills needed for making jigsaw puzzles are similar to those that were needed for wartime production. Jigsaw puzzle workers left for jobs that were both better paying and considered more patriotic. It became difficult for puzzle makers to hire sufficient staff to meet even the newly-limited demand.

During the War, jigsaw puzzle makers also experienced what we now call “supply chain problems” for the necessary materials. Good quality plywood in particular was essential for military needs and therefore difficult for them to obtain. In England, fine paper itself became unavailable for production that was not related to the war effort.

Early in the war, Hayter’s company would also have faced additional difficulties because its factory in the suburbs of Bournemouth was only a few blocks from a beach on England’s southern coast. There would have been many air raids, as well as extensive travel restrictions and security arrangements in that part of England, which was the region that was most vulnerable to infiltration by spies or attack.

As a result of this sudden shift, most of the jigsaw puzzle companies which made other products that qualified as wartime production focused on that side of their business, and they either suspended or greatly reduced making jigsaw puzzles for the duration. But G.J. Hayter & Company had no products except its jigsaw puzzles so it struggled through the war at a reduced scale.

Hayter shifted most of its production to children’s puzzles (at least partly because they were easier to cut and with their smaller sizes could be made from plywood that would otherwise have been scrap) and his puzzles for adults often emphasized patriotic themes in their images and whimsies. The company also publicly promoted the contribution it was making to the war effort by providing puzzles for recovering patients in military and civilian hospitals. The above whimsy of a diver was from a puzzle that I believe was made during this wartime era.

Post-war doldrums

After the War, supply chain problems continued in Britain and rationing continued for a few years. Because the jigsaw craze was over many of Hayter’s competitors never did return to making puzzles. Perhaps more importantly, the general public was now more prosperous and they wanted to put their depression-era culture lifestyles behind them.

As a hallmark of this, new consumer society people turned towards products that were short-lived and disposable. In the case of jigsaw puzzles that meant cheap cardboard puzzles which could be assembled once and then thrown away or passed along to others suited the new mindset better than durable wooden ones. Improvements in the technology of die-cutting and the quality of cardboard, as well as production techniques learned from the demands of wartime production combined to make cardboard puzzles much, MUCH less expensive than labour-intensive hand-cut wood puzzles could ever be.

The wooden jigsaw puzzle companies that did return to production after the war limped along for a few years but all of the Golden Age factories except Hayter stopped making wood puzzles for adults over the next decade. Interestingly, none of them transitioned to making cardboard jigsaw puzzles. For the most part, the realm of wood jigsaw puzzles for adults largely returned to its earlier roots – hand-made items individually made by skilled craftspeople in small workshops, affordable only by the affluent or through puzzle library rental programs run by such craftspeople.

Gerald Hayter’s company got a brief bump in 1952 when King George VI died and especially the next year when Britain used the coronation of the new Queen Elizabeth II as a symbolic celebration of both the nation’s heritage and the end of wartime austerity. Sales in royal family memorabilia boomed, and heirloom-quality wood puzzles suited the occasion much better than cardboard throw-away ones. Hayter issued thirty-five different puzzles depicting such subjects as the new Queen, Prince Phillip, the baroque Coronation Coach, and soldiers and guards performing Royal duties.

This time was the peak of G.J. Hayter & Company’s post-war production, employing about 100 people including 50 cutters, a significant drop from the 1930s scale of production. After the Coronation binge the company was back to a struggle for survival. Hayter stayed in the business longer than the others partly by focusing mainly on children’s puzzles and also by extending its Victory brand into other plywood toys for children like ping-pong paddles.

I suspect that the rise of television was also a very important aspect of the changing times and recreational interests. The audio-only aspect of radio meant that it could complement rather than compete with jigsaw puzzles as a family activity. However television is different: It is a magnet for both peoples’ ears and eyes.

The company continued to make puzzles for adults through the 1950s and ‘60s, dropping old images and introducing new ones to keep up with changing public interests. But each new annual Hayter catalog documents that the company was becoming more of a manufacturer of puzzles, games and toys for children, and fewer and fewer puzzles for adults were listed.

I know very little about what it was like to work in Victory’s Jigsaw puzzle factory in Boscombe, in the suburbs of Bournemouth, either during its heydays during the 1930s or after the war. However Andrew Knowles was recently able to find two photos that are dated circa 1965. This first one is of cutters turning the mounted prints into jigsaw puzzles:

I was surprised to see how closely the cutters are working near each other, since by 1965 the number of workers at the Boscombe factory was so greatly reduced from what they had been in the 1930s. There is also no sign of task lighting, and I can’t see any vacuum system to remove the sawdust.

My first job was in a factory in 1965, so having only male factory workers does not strike me as unusual for that time period, but I was struck by how young many of these employees look. Perhaps it is just my perspective now as an old coot, but most of them look like teenagers, and none of them look like the middle-aged and old men who constituted the majority of my co-workers in 1965 when I looked much like that young fellow in the middle of this picture.

This next photo is workers putting the pieces into their boxes:

Again, they are working in closer proximity to each other than I would expect, but the elephant in the room is that this job is done exclusively by women, as distinct from the better-paid young male cutters.

Elsewhere in the plant there would have been workers doing the many other jobs that are essential for making wood jigsaw puzzles and the boxes to put them in. Besides cutting and sanding the plywood blanks and gluing their images to them, and making the boxes, there would have been many ancillary roles such as warehousing of raw materials and finished product, shipping, and of course cleaning up all that sawdust. In the office in those pre-computer times there would have been workers managing the purchase of supplies, correspondence related to sales, bookkeeping, payroll, and all of the other paperwork that manufacturing entails.

Coordinating and managing all of this through good times and bad must have been hard work for Mr. Hayter, and supporting him must have been a challenge for his anonymous (to me) wife. [Note: You may have noticed that my account has been quite deficient regarding information about the Hayters’ personal lives. I don’t even know if they had children. I hope someday to learn more about them, as well as about the working conditions of the workers.]

Continuing under a new owner

In 1970, at the age of 69, Gerald Hayter sold his company to J.W. Spear & Sons Ltd., one of Britain’s foremost toy and game manufacturers. The Spear company is most famous for holding the worldwide rights to manufacture and sell the board game Scrabble in all markets outside of North America.

J.W. Spear & Sons has an interesting history in its own right. The company had been founded in 1879 by Jewish businessman Jacob Wolf Spier (1832-1893) near Nuremberg, Germany. Initially they made a variety of products but by the turn of the century, games had become their main focus.

In 1932, the company set up a branch factory near Enfield in Britain and the members of the family who moved there to run it Anglicised their name to Spear. Ostensibly the reason that they established this subsidiary was to avoid customs duties. But to give this decision context, the handwriting was on the wall in Germany for Jewish people. That is the same year that the Nazis became the largest political party in Germany’s Reichstag.

As the Nazis rose in power, and oppression of the Jews increased, more of the Spier family moved to England. In November 1938, right after Kristallnacht (The Night of Broken Glass), like many Jewish-owned businesses, the company’s German factory was forcibly sold at a bargain-basement price to a non-Jewish owner. Hermann Spier, the dispossessed director of the Nuremberg factory was jailed many times by the Nazis and later died in Auschwitz. Now commonly known as Spear’s Games, the English branch of the company remained a family-run business until 1994, when it was sold to Mattel after a fierce bidding war with Hasbro.

But back to 1970. Spear & Sons moved the manufacture of most of the Hayter company’s children’s products, including its children’s puzzles, to its own factory 124 miles away in Enfield, on the north side of London. But it continued to make puzzles for adults at the Hayter facility in Boscombe. At first, G.J. Hayter & Company continued as a subsidiary of its new owners but it was later identified on its packaging as being a division within the Spear company.

The Boscombe factory became a shadow of its former self. Besides having production of all children’s products moved to Enfield, Spear greatly reduced the production of adult puzzles, dropping the Topical series entirely and greatly reducing the number of puzzles made in the other series.

In 1980 J.W. Spear & Sons greatly streamlined the lines of Victory puzzles that the Hayter company had been making for adults, discontinuing ALL of the various lower-priced series as well as the higher-priced Super Cut one. All of the Victory puzzles were now called Victory Gold Box Plywood Jigsaw Puzzles.

The cutting design for these Gold Box puzzles was similar to what had previously been the Artisan series, having rather simple figural pieces within a matrix of more-or-less square pieces with tabs to make them interconnect. However as a way to speed up cutting and reduce costs, cutters stopped making a lot of the internal interconnecting tabs, replacing them with an easy-to-cut wavy line. Now many of the pieces only had tabs on two or three sides of the piece.

In my review-essays of one such puzzle here in which I observe that this cost-cutting measure actually seems to have been a win-win. I found that replacing some of the interconnecting tabs with a wavy side actually makes assembly more interesting and more challenging than when the Artisan puzzles had been fully interconnected.

These Victory puzzles continued to be packaged the old-fashioned way, in their classy gold boxes and without a cover picture or any information other than a title and brief vague description to indicate what the puzzles image would be. Over time the number of puzzles on offer grew fewer and fewer. The new organization of the product line grouped them into series according to their number of pieces. In the latter years even the most popular sizes only had about 12 puzzles available at any one time.

In 1988 the Spear company discontinued making puzzles for adults completely and closed the Bournemouth factory. After over 70 years of Victory puzzles, the company that began as a hobby and grew to become the largest and longest-lasting company from wooden jigsaw puzzles’ Golden Age seemed to have come to an end.

Shortly after they closed the factory Spear licensed the Victory name to Waddington and the next year that company sold a series of eight laser-cut “Waddingtons Victory” puzzles. They were made of wood but their fully interlocking ribbon cutting design (no whimsies) was exactly like their cardboard puzzles and all 8 puzzles had the same cutting pattern. I don’t think that anyone considers these puzzles to be “canon” Victory puzzles although that brief episode may deserve a place in wooden jigsaw puzzle history: As far as I know these were the first commercially-made laser jigsaw puzzles, coming to market about five years before Wentworth’s inaugural puzzles.

A new Victory

On September 21, 2022, Bournemouth-raised Andrew Knowles announced that he, his son Aidan, and friends James and Toby Martin have formed a new company that will revive making Victory brand wooden puzzles in that City. Since the name Victory is considered abandoned they have been successful in registering trademark of it for their new company, which is called Victory Wooden Puzzles.

Like Gerald Hayter before them, they began as a small workshop-scale operation but using the new computer-controlled laser-cutting technology that Gerald could never have even dreamed about. In doing so, at the time they took on a David vs. Goliath challenge. While laser-cut puzzle companies had become fairly common in other countries (Canada alone had 6 of them) in England the giant Wentworth company absolutely dominated the laser-cut wooden puzzle marketplace.

Their new company was launched with ten puzzles with varying styles of artwork in their initial offering. Artistically trained Aidan Knowles was their inaugural cutting designer, and James and Toby Martin, who also ran a printing business, made the puzzles in their workshop which is less than 10 miles from the location of Gerald Hayter’s former factory in Boscombe.

Within a few years they found it more efficient to contract the actual puzzle-making side of the operation to a manufacturer in China. At at the same time they increased the thickness of their puzzles from 3 mm to 5 mm (to compete with Wentworth which, within a few months of the new company’s founding had raised the thickness of their puzzles from 3 mm to 4mm. But the new Victory company is still true to its predecessor’s roots, primarily making puzzles at the more frugal end of the wooden puzzle marketplace.

Most of their currently-available puzzles appear to be designed to reflect the general style of Hayters’ Artistic puzzles, although updated with interesting twists on the grid-cutting of the background pieces, and more-elaborate whimsies that (unlike in the Hayter era) are thematically linked to the puzzles’ images. More recently they have launched their own premium series that they call Artisan, which are 7 mm thick laser-cut replicas of puzzles that are designed and cut by the highly-respected American master hand-cutter Mark Cappitella.

In one sense these Artisan puzzles are a return to Victory puzzle’s roots when all of Hayter’s puzzles were hand cut, but in another it might be more accurate to describe them as building on that foundation. They are more reflective of just the old Super-Cut series, and unlike that company’s cutters Mark is under no time pressure to cut efficiently so there is no need to stick to efficient strip grid-cutting. He can cut free-hand and include whatever inefficient design tricks, like colour-line cutting, the image inspires in his artistic spirit. Being hand-cut, the whimsies are less intricate than the ones that Aidan designs digitally (but personally I prefer such artistic silhouettes.)

For more information about what fans are calling Victory 2.0 or Victory Reboot, and to order their puzzles, go to their website.

Great stuff, Bill. Just a footnote about the end of Victory. After Spears & Co folded in 1988, the Victory name was purchased by Waddington's, and they put out a series of 8 laser cut wooden jigsaw puzzles under that name in 1989. This was a short-lived experiment though. You will find some examples on Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/140550140@N03/29100976892. Best wishes, Wout, Groningen, Netherlands.

The Hayter/Victory history is interesting. I feel amazed by the depth of your research. Often, when I feel motivated to research something on the Internet, I quickly get sidetracked because some unusual phrase will remind me of a song recorded by, say, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, and I will then spend the subsequent hour tracking down and listening to golden oldies! However, I admire your level of research. The photo of the table tennis set looks awfully familiar. I don't recall the brand name on the box that was "archived" in my parents' home, but it was the set with which I learned that game/sport. It may well have been a Victory product. Besides a few minimal-piece, cardboard-tray jigsaw puzzles with images such as Donald Duck or Mickey Mouse, the first "serious" jigsaw puzzle I can remember was given to me at Christmas the year I was five. It was a plywood puzzle of perhaps 100 pieces made by Knightsbridge. I can see that vintage puzzles by that company are still advertised on-line. I haven't yet seen any history of the company, though. Thanks for your latest posting, Bill.