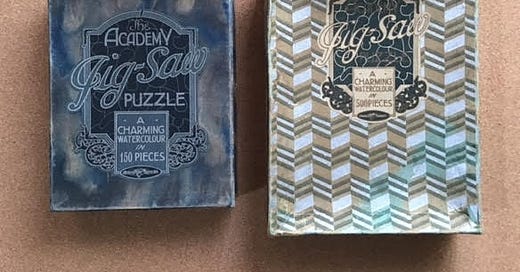

5. Jigsaw puzzle history and two J. Salmon "Academy" vintage puzzles

A history of jigsaw puzzles, and accounts of two vintage ACADEMY brand puzzles made by J. Salmon & Co. in 1927 and 1933. (about 4000 words; 21 pictures)

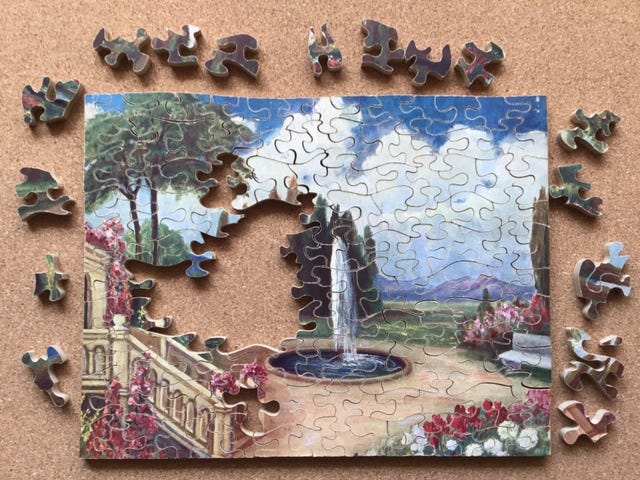

Garden & Fountain

factory hand-cut Academy puzzle made in 1927 by J. Salmon Ltd.

artist - unknown

150 pieces 8½” x 11” (21 x 27 mm) 5/16” (8mm) hardwood

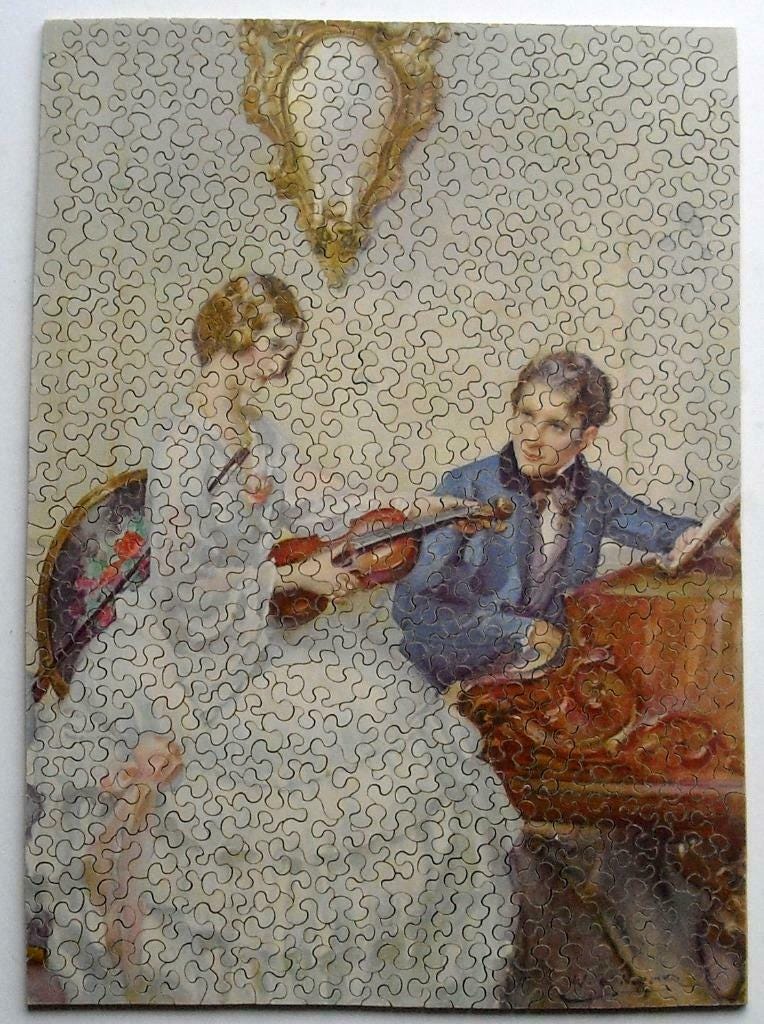

Perfect Harmony

Factory hand-cut Academy puzzle made in 1933 by J. Salmon Ltd.

artist –W. E. Webster

500 pieces 18” x 12” 5mm hardwood 3 ply

Since my last jigsaw puzzle was a newly-released one I thought I would go to the other end of the time spectrum next and assemble my oldest puzzle, a 150 piece one made in 1927. But assembling it went too quickly so I decided to pair it for this essay with another one made by the same company six years later. I knew that its 500 pieces would be a challenge, but I never suspected how big of a challenge that puzzle would prove to be.

These two vintage puzzles are from two stages of wood jigsaw puzzling’s brief “golden age” that lasted from the beginning of the 20th century until World War II. During that time assembling such puzzles suddenly became a very popular hobby for adults in all social classes in England, the US and other countries. Ironically, the peak of that golden age was during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Then, as quickly as the wood jigsaw puzzle craze had arisen, it died away. It takes a short history lesson to explain why.

A brief jigsaw puzzle history lesson

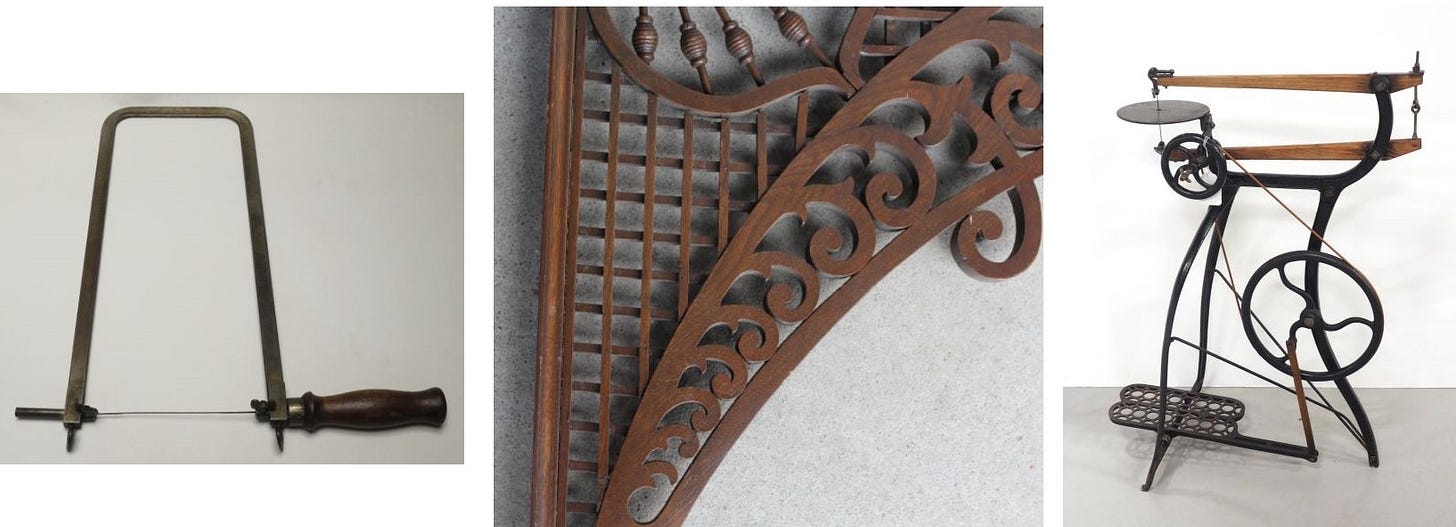

Jigsaw puzzles were first invented in the 18th century. There is evidence in old correspondence that many people in Europe were either suggesting or considering making cut-up maps as a teaching tool for the children of aristocrats. But the oldest examples of this having been done are by an English map-maker named John Spilsbury, a young engraver who was fresh out of apprenticeship with Thomas Jefferys, the Royal Geographer to King George III. Around 1765 he pasted a map of England onto a thin sheet of mahogany board and used a hand-held fret saw to cut it into pieces primarily along the borders of counties.

The resultant “dissected map” was intended to help Spilsbury’s wealthy clients’ tutors teach geography to the clients’ children. His dissected maps became a popular product for the young entrepreneur. Spilsbury himself died quite young, at the age of 29, but his idea caught on with the upper classes. Soon other printers in England and other countries in Europe began offering similar dissected pictures for teaching geography, history and holy scripture to wealthy customers’ children.

Over time the images became less didactic and dissected pictures evolved into a children’s toy or game, not just a teaching tool. But as hand-made items made from expensive materials they were still very costly (the equivalent of an average worker’s weekly wage) and they were thought of as only being suitable for children.

In the 1800s, decorative fretwork became very popular for residential architecture and cabinet making, and foot-powered treadle fret-saws (also called marquetry- or scroll-saws) were invented for the time-consuming job of making fret-work. They were possibly modeled after the also newly-invented sewing machines, although they were mechanically much simpler. Like sewing machines they greatly reduced the time needed for the task. Treadle fret-saws made the task of cutting intricate curves less tiring and much quicker. They were fairly simple inexpensive machines and before long most cabinet makers and carpenters makers owned one.

Those cabinet-makers, carpenters and other crafts-people quickly found that they could use these tools to make the previously-exclusive teaching toy that came to be called jigsaw puzzles for their own children and for those of their friends and customers. As I understand it, it was these working-class artisans not the high-end English puzzle-makers who first began to paste sophisticated art prints onto boards and cut them into smaller pieces to, thereby making puzzles suitable for adults.

I think it is an interesting twist that the next step was that this innovation by artisans was copied by the high-end English puzzle-makers. When they began making adult puzzles for their wealthy clients it started a recreational craze that swept through the social upper crust. Besides couples or individuals assembling them in the privacy of their homes, jigsaw puzzles soon became a prestigious alternative to Bridge and other card games as an indoor social activity for hosts to enjoy with their guests, especially during the long rainy days or dark evenings in wintertime. The most popular sizes were puzzles that had a number of pieces that could fit on a standard card table and could be completed by up to four people in a single sitting.

Three more innovations from near the end of the 19th century are still hallmarks of good wood jigsaw puzzle design for adults. These are: colour-line cutting (cutting along the lines separating different colours in the image to make assembly more challenging); the invention of interlocking pieces, so that progress was less likely to be disrupted by a bump of the table or the brush of a sleeve; and entertainingly cutting some of the pieces into recognizable shapes (now called whimsies, figure pieces, or figurals.) [Note: of these, only interlocking pieces are common in today’s cardboard jigsaw puzzles. Figurals and colour-line cutting are difficult to do using die-cutting.]

Beginning in the early 20th century engraving and lithographic publishers recognized that a promising new business opportunity was emerging for which they were already making one of the most important components. They began to make jigsaw puzzles in their factories, applying assembly-line production methods, and they began using less-expensive materials and packaging. An important technological advancement that helped were improvements in the manufacture of plywood, including the use of softer, less brittle hardwood (especially birch) that made pieces less susceptible to chipping and warping. Although making wood puzzles were still very labour-intensive this brought down their price to make them more affordable for the rapidly expanding number of potential middle-class customers.

The fact that jigsaw puzzles were already popular among wealthy people and the aristocracy was an important marketing device: The manufacturers were offering middle-class customers a opportunity to emulate an aspect of the lifestyle of their social betters. For example, in both its British and American marketing the firm Raphael Tuck played on its Royal Warrant (for stationary) and aristocratic reputation to describe their puzzles as: “Incomparably the Best. . . . A most fascinating recreation, used by Royalty, Society and the great public.”

Besides being prestigious home-based recreation, unlike the very cheap but fragile newly-invented die-cut cardboard jigsaw puzzles that tried to jump on the same bandwagon, wood puzzles were durable and could be used over and over, and could be loaned or traded with friends.

It is ironic that the next big factor in expanding wood jigsaw puzzles’ Golden Age was the Great Depression. Through the 1930s the jigsaw puzzle craze moved further down the social ladder, from the middle-class to also include many working-class families. Wood jigsaw puzzles came to be seen by many people at all levels of society as being a wholesome, frugal, home-centred, enjoyable social activity. The sale of of wood puzzles of varying levels of quality boomed during the Great Depression. I suspect that for many people, listening to radio broadcasts accompanied their evenings’ puzzling.

Unemployed labourers found employment in the wood jigsaw puzzle factories, one of the relatively few types of manufacturing that was growing and hiring during the Great Depression. Also, with only a modest investment in equipment, individuals could start their own one-person jigsaw puzzle businesses. Many of the their puzzles recycled pictures from magazines or calendars for their artwork. It is not a coincidence that common sizes for jigsaw puzzles at that time were the dimension of the tops and bottoms of wooden cigar and tea boxes.

Business models for the larger companies included sales through department stores and drug stores, manufacturing commissioned advertising puzzles for such companies as the Cunard White Star Line and the Great Western Railway, and producing regular weekly releases of new puzzles to be sold at news-stands. Some of them even depicted images from the current headlines. For local one-person companies, besides selling their puzzles in local stores they could offer home delivery (often as a side-gig for milkmen.)

One limiting factor was that for many enthusiasts the appeal of a jigsaw puzzle came from its challenge. Once completed, those folks wanted to take on new challenges rather than re-assemble a puzzle they had already conquered. So many independent wood puzzle makers began to rent them as well as selling them. Also, jigsaw puzzle lending-libraries and clubs that had puzzles made by several cutters and companies were formed and they also flourished during those economic hard times. This was a distribution format that was (and still is) unsuitable for cardboard puzzles.

This golden age stayed strong though the Depression but puzzle makers faced significant difficulties during World War II. Demand subsided since family and social life was greatly disrupted since many people entered the military or assumed war-related volunteer roles, or they worked overtime hours in the very busy wartime production. Also, the skills needed for making jigsaw puzzles were similar to those that were needed for wartime production, and working for those firms was both better paying and considered more patriotic. It became difficult for puzzle makers to hire sufficient staff to meet even the newly-limited demand.

During the War and in the years shortly thereafter, jigsaw puzzle makers also experienced what we now call “supply chain problems” for the necessary materials. Good quality plywood in particular was essential for military needs and therefore in short supply. In Britain, fine paper itself became unavailable for production not related to the war effort. As a result, the companies that also made other products that qualified as wartime production focused on that side of the business and suspended or greatly reduced jigsaw puzzle production for the duration. A few companies, like G.J. Hayter who made the “Victory” branded puzzles, struggled through at a reduced scale. They emphasized patriotic themes in their images and publicly promoted the contribution they were making to the war effort by making puzzles for recovering patients in military and civilian hospitals.

After the War other factors ushered in a transition to cardboard jigsaw puzzles. Improvements in the technology of die-cutting, and reduction in the price and improvement in the quality of cardboard, made that less-durable alternative much, MUCH less expensive than the labour-intensive hand-cut wood puzzles could ever be. I suspect changing times and recreational interests, including the rise of television over the audio-only entertainment of radio, also contributed to the decline of jigsaw puzzling in general at that time.

A few wood puzzle factory companies limped along for a few years but all of the golden age companies stopped making wood puzzles for adults over the next few decades. Interestingly, none of them transitioned to making cardboard jigsaw puzzles. The realm of wood jigsaw puzzles for adults largely returned to its earlier roots – expensive luxury items individually made by skilled craftspeople, affordable only by the affluent.

A very recent technological leap has brought wood puzzles for adults back into a significant scale of production, and affordability, but that is a story for another time.

[Note: Because the puzzles accompanying this essay were made by a British firm I have tended to focus this abbreviated history on that country. The history of jigsaw puzzles in the US and Canada parallels what happened in England, but only begins in the latter 19th century. For a brief overview of the American scene I suggest this account by Dr. Anne D.Williams, an academic historian who specializes in American jigsaw puzzles.]

J. Salmon & Co.

The British manufacturer of the two puzzles featured in this review/essay was one of those golden age factory wood jigsaw puzzle companies. The story of its rise and fall mirrors the story of its competitors.

The firm had been founded in 1880 as a stationary and printing company that specialized in making post cards and calendars. In 1920 the company recognized the increasing popularity of jigsaw puzzles and began producing them in their factory using foot-powered treadle scroll saws and sold them under the brand name ACADEMY.

By the 1930s J. Salmon employed thirty cutters and an equivalent number of other types of workers performing the various steps needed for jigsaw puzzle production. The company’s puzzles were in the same general price range as the industry leaders in Britain at that time - G. W. Hayter (maker of the Victory brand), Chad Valley, and Raphael Tuck (Zag-Zaw.)

As with most other British companies, J. Salmon & Co.’s production of puzzles was curtailed entirely during WWII. They re-started puzzle production right after the war in 1946 but it was clear that they could not compete with the price of cardboard puzzles (which required expensive equipment and had to be made in very large quantities but were by then of improved quality due to technical improvements in both cardboard-making and die-cutting.) The company discontinued making wood puzzles in the 1950s and re-focused back to its well-established publishing leadership in English calendars and postcards.

Fortunately, Brian Sulman, a collector of Academy puzzles, has researched and provided good documentation for the over-1400 puzzles that were issued by the company during the thirty or so years that it made them. Based on studying the company’s occasional catalogs, and the evolving designs and prices on their labels, he is able to give production dates for most of the puzzles they released.

In recent years, smart phones and the internet have greatly reduced demand for both postcards and paper calendars. The company tried to retrench into cookbooks and travel picture-book guides but it was too late. In 2017 J. Salmon & Co. Ltd was forced to closed its doors for good. Through its entire 137 years the company had remained a family-owned firm (five generations) and had operated from the same premises at 100 London Road, Sevenoaks, Kent!

Garden & Fountain

I bought both this Academy puzzle as well as its Perfect Harmony sibling from eBay auctions by a seller in Essex, England. The seller had reliable information about this puzzle’s 1927 origin date since it is included in Brian Sulman’s “encyclopaedic work” The ACADEMY series of Jig-Saw Puzzles.

I have been unable to identify the artist who painted this picture. According to Tom Tyler’s 1997 book British Jigsaw Puzzles of the 20th Century, J. Salmon sometimes commissioned artists to produce original pictures for them. As far as I can tell, even when their puzzles’ artwork was the reproduction of a famous painting (as is the case for this puzzle’s companion) their packaging did not identify the artists.

This puzzle is from before J. Salmon followed other puzzle-makers’ lead and transitioned from using thin hardwood board to using plywood as their base material. Normally that would make such a puzzle quite sought-after by collectors. But I remember thinking at the time that because the subject matter of the artwork is rather bland, and it is only 150 pieces, that this one might attract less attention from them. It turns out I was correct. I was able to buy it for £27.

The first thing I noticed after opening the box is how thick the pieces are. It was only more recently that I noticed that they also vary in thickness from about 7 to 8 mm across the span of the puzzle. J. Salmon’s advertising (on the inside of the box lid) says that all of their puzzles are made from the “best quality satin walnut wood.” It is clearly hardwood but the colour of this wood is not the rich colour that one associates with walnut: It is more like the colour of maple or birch. (Satin walnut sapwood is light in colour but not this light.) I speculate that when this puzzle was made while the company was experiencing a “supply chain problem” with their favoured wood.

As you can see, the assembly proceeded in a rather routine manner, beginning with the edges and following blocks of colour and distinctive features.

J. Salmon described this and their other puzzles at the time as “all pieces interlocking” but as you can see many of the horizontal cuts do not interlock. I am not complaining about that. Because of the limited number of pieces in this puzzle, and the distinctive regions of colour in the image, this was the easiest and quickest puzzle that I have assembled so far. That limited interlocking was about the only feature of this puzzle that made it challenging.

Despite the fact that this was not a very challenging puzzle and its artwork is rather uninteresting, this was an enjoyable puzzle to assemble. Much of that came from the fact that the thick hardwood pieces were a constant reminder that this is a 95 year old puzzle, made when the jigsaw puzzle craze was still in the ascendency and that it still reflected elements of the earlier pre-factory era when they were a luxury item. The thick, large pieces did evoke that time, and the colours were also fairly bright (although not anywhere near the vibrancy that is now routine with modern UV printing.)

Perfect Harmony – the artist

In the case of this other Academy puzzle I was able to identify the artist even though J. Salmon & Co. didn’t identify him. I ran the image of the completed puzzle (that had been in the eBay posting) through Google’s image search. I was somewhat surprised that it worked because the puzzle piece lines are so prominent in the photo.

The artist was the British painter and illustrator Walter Ernest Webster (1877-1959) who had been trained at the Royal Academy Schools and the Royal College of Art. Webster specialized in portraits and figure paintings (clothed and unclothed) of young women using a flattering soft, fluid style. He exhibited at all of the major British art institutions as well as at the Paris Salon where he won a gold medal in 1931. Webster was commissioned by the British Government Art Collection to paint two portraits of Queen Elizabeth, a watercolour when she was still a princess and an oil painting shortly after her coronation in 1953. (Neither image seems to be available online.)

The painting used for this puzzle was an illustration commissioned by The Etude music magazine, published by the Theodore Presser Company from 1883-1957.

Webster’s paintings are sometimes described as impressionist. I can’t see that in this puzzle’s image, but I can see it in some of his other paintings.

Perfect Harmony

Because the assembly of Garden & Fountain had gone so quickly, and I had so little to say about it, I decided to pair it for this essay with another vintage puzzle from J. Salmon’s Academy series. Because a number of them have come up at action recently I had a few to choose from. I decided to contrast it with this much more difficult one that was made in 1933 (again, the date is based on Brian Sulman’s research, and in particular, the price label.)

I had bought it for only £36. Even with my limited experience with vintage puzzles I knew that was a very good price for a complete 500 piece puzzle of that era. I also knew that its size would make it a challenge for me, and that the artwork would present its own complication: After I completed the more colourful regions I would be left with large areas with very little colour differentiation in various shades of blueish-beige. But after such an easy puzzle I felt ready for a challenge.

I knew from when I had bought it that, like Garden & Fountain, there are no figure pieces (AKA, whimsies) in this puzzle. Only after pouring out the pieces did I become aware that the pieces are much thinner and that its cutting style is very different from the other puzzle. At 7-8 mm thick, and with mostly smooth languid curves, the wood pieces for Garden & Fountain seemed robust but graceful. By contrast, the tight swirling curves of the 5 mm thick plywood pieces in Perfect Harmony seem delicate and rather frantic. They were both from the J. Salmon cutting designer(s?) but comparing their cutting is like comparing a mature English sheepdog to a chihuahua puppy.

In retrospect, I should have recognized at this stage that I was taking on a bigger challenge than I wanted. After an unusually cold, wet Springtime, Summer was finally arriving here on the west coast of Canada. Gardening, more time with my 6 year-old grandson, and lawn bowling season is not the time to take on a time-consuming indoor task. And there are a LOT of bluish-beige pieces in this puzzle. Summer isn’t the right time of year for beige.

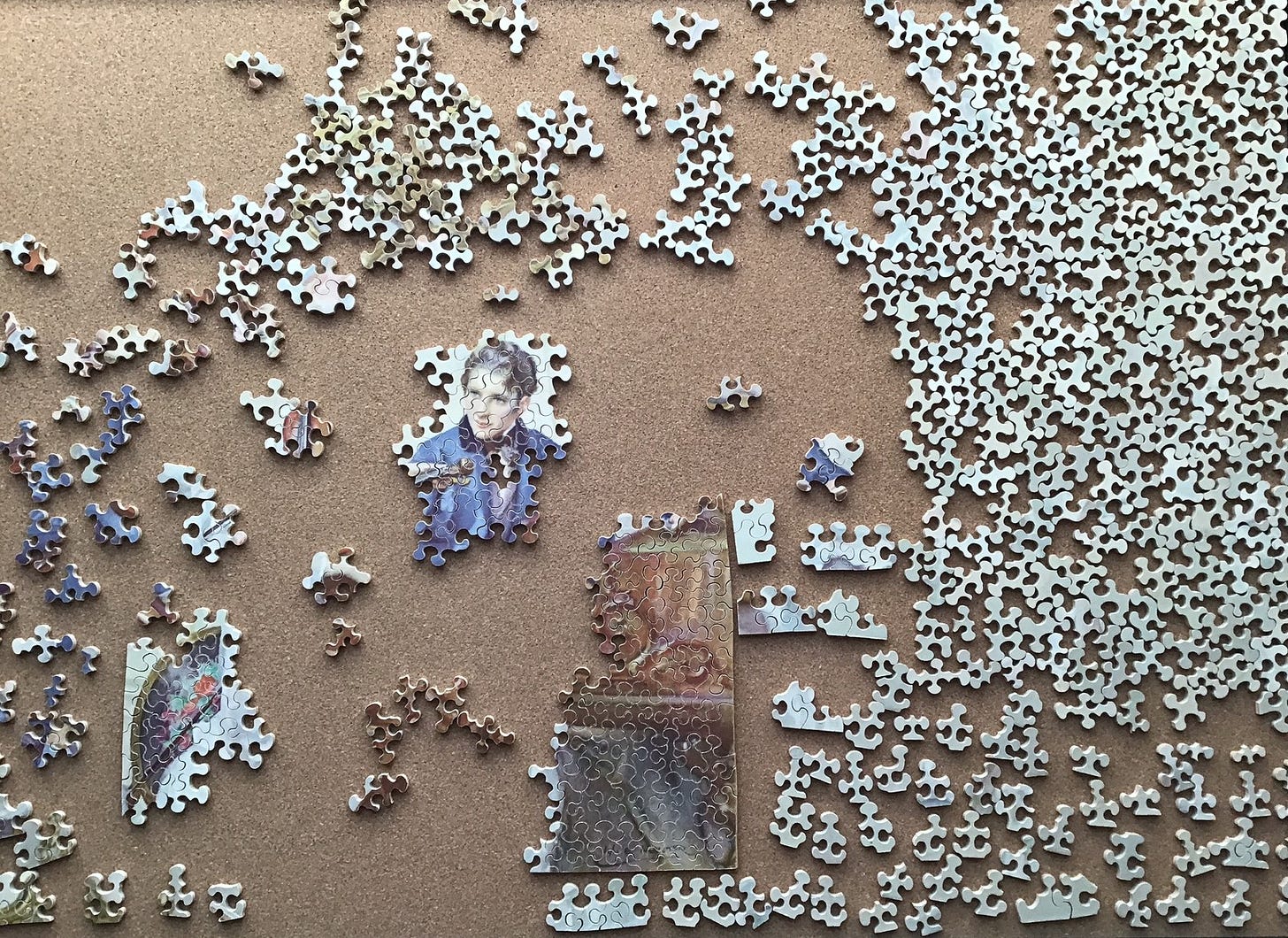

Perfect Harmony - assembly

As was typical at that time, J. Salmon did not put the picture on the box or include a reference image so I didn’t have any accidental recent glimpses of what puzzle would look like. But I had bought it about a month earlier and still had a vague memory of its composition from the photo of the completed puzzle in the posting. I remembered that most the brown pieces were probably the piano or harpsicord, and that the dark blue pieces were the jacket of the man who was playing it.

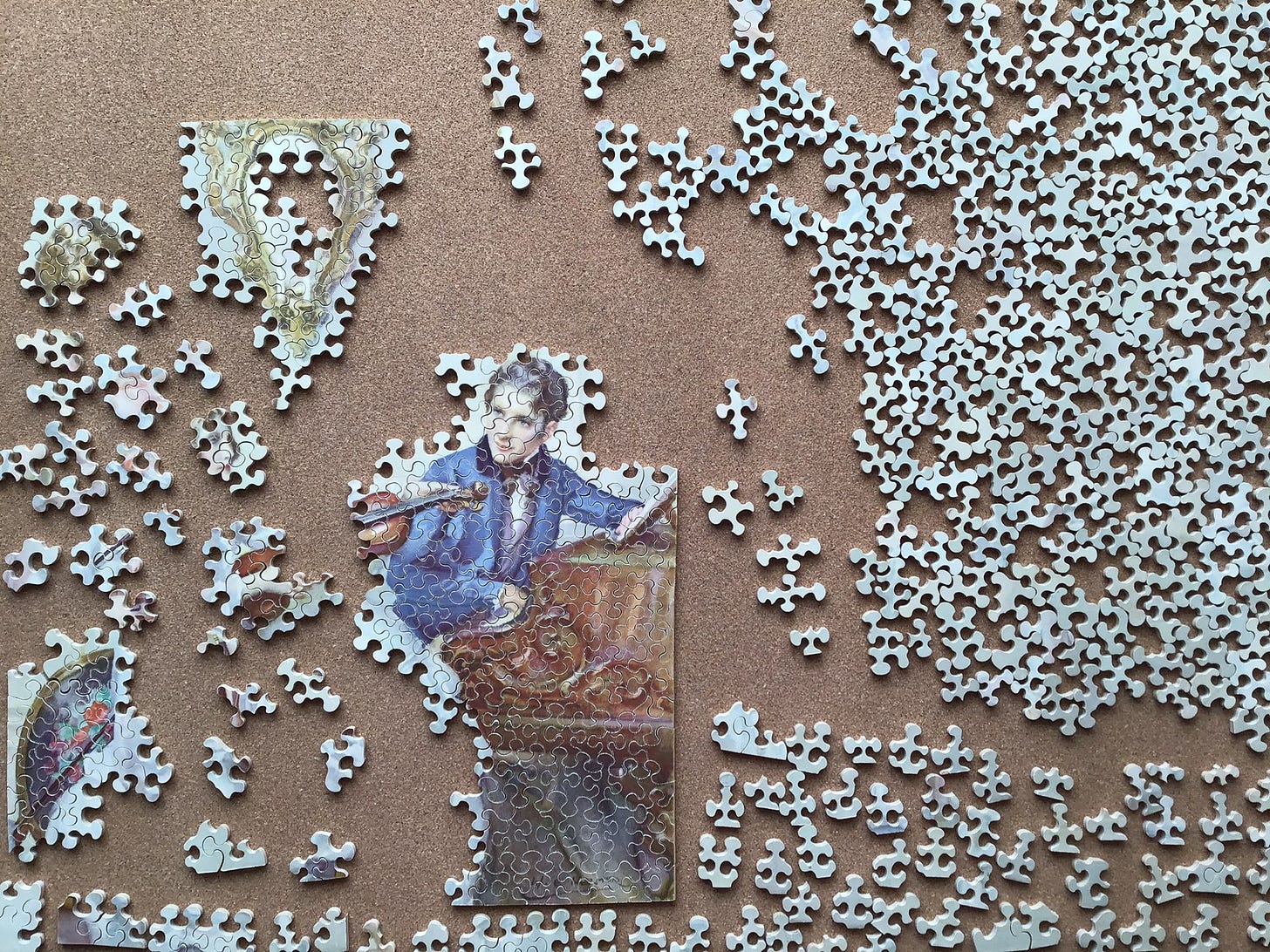

I began with the brown edge pieces and then worked my way through the other adjacent brown ones. As a break from that I worked on the man’s face and the blue of his jacket. The other dark pieces turned out mostly to be the shadowed area under the piano, and a mysterious fan-shaped thing that I did not remember being in the image..

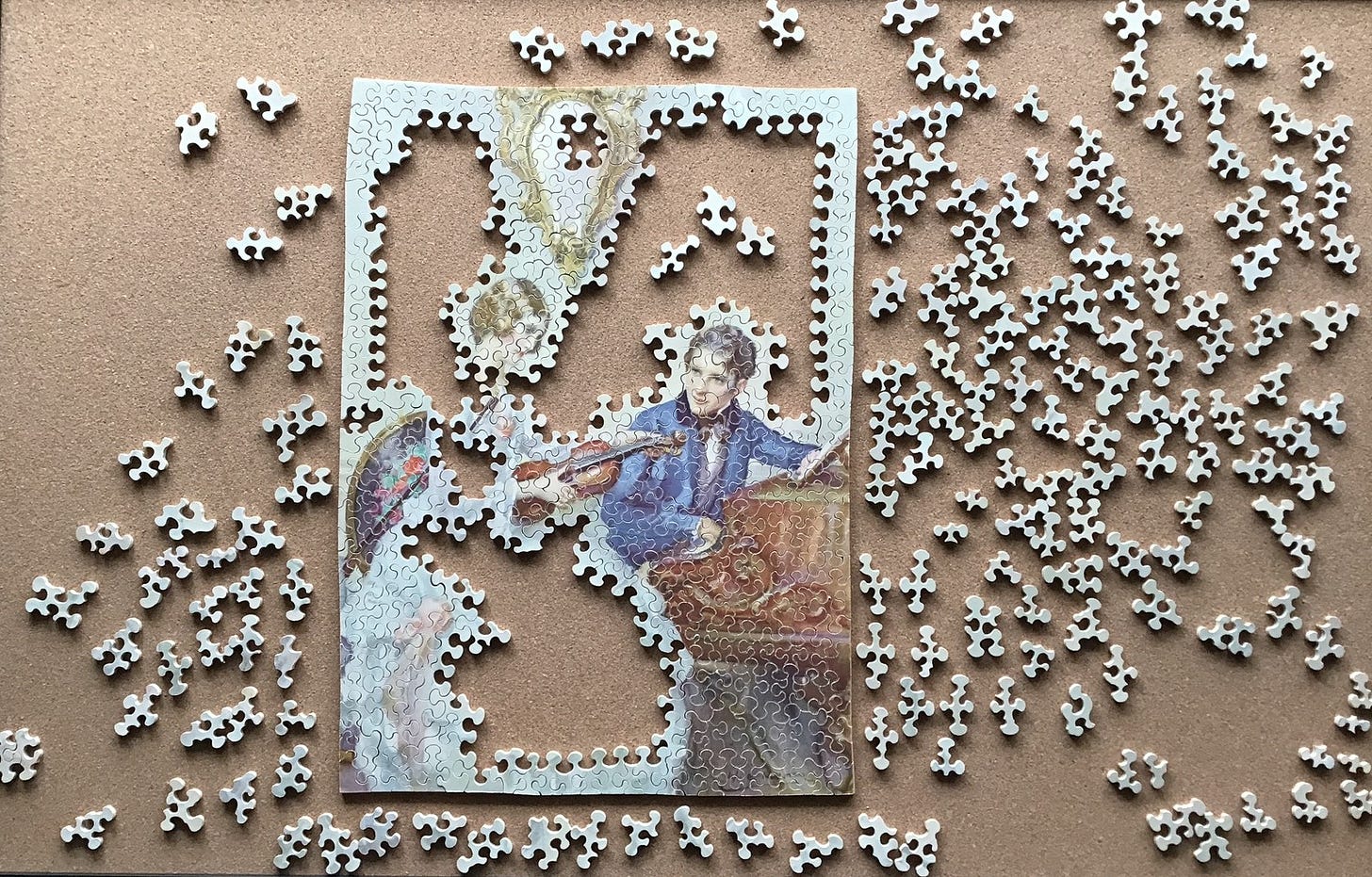

I continued with what targets of opportunity the coloured pieces gave me and the edge pieces that included colour. I recognized that there was a baroque gilt mirror behind the young woman. This drew my attention to the fact that this nearly 90 year old image has fugitive colours – i.e., some colours fade differently than others. In the puzzle things that were obviously supposed to be 24k gold-leaf looked a pale yellowish-green. Even parts of the piano were a pale greenish-brown shade.

The whole image has a very soft focus look to it with few distinct lines.

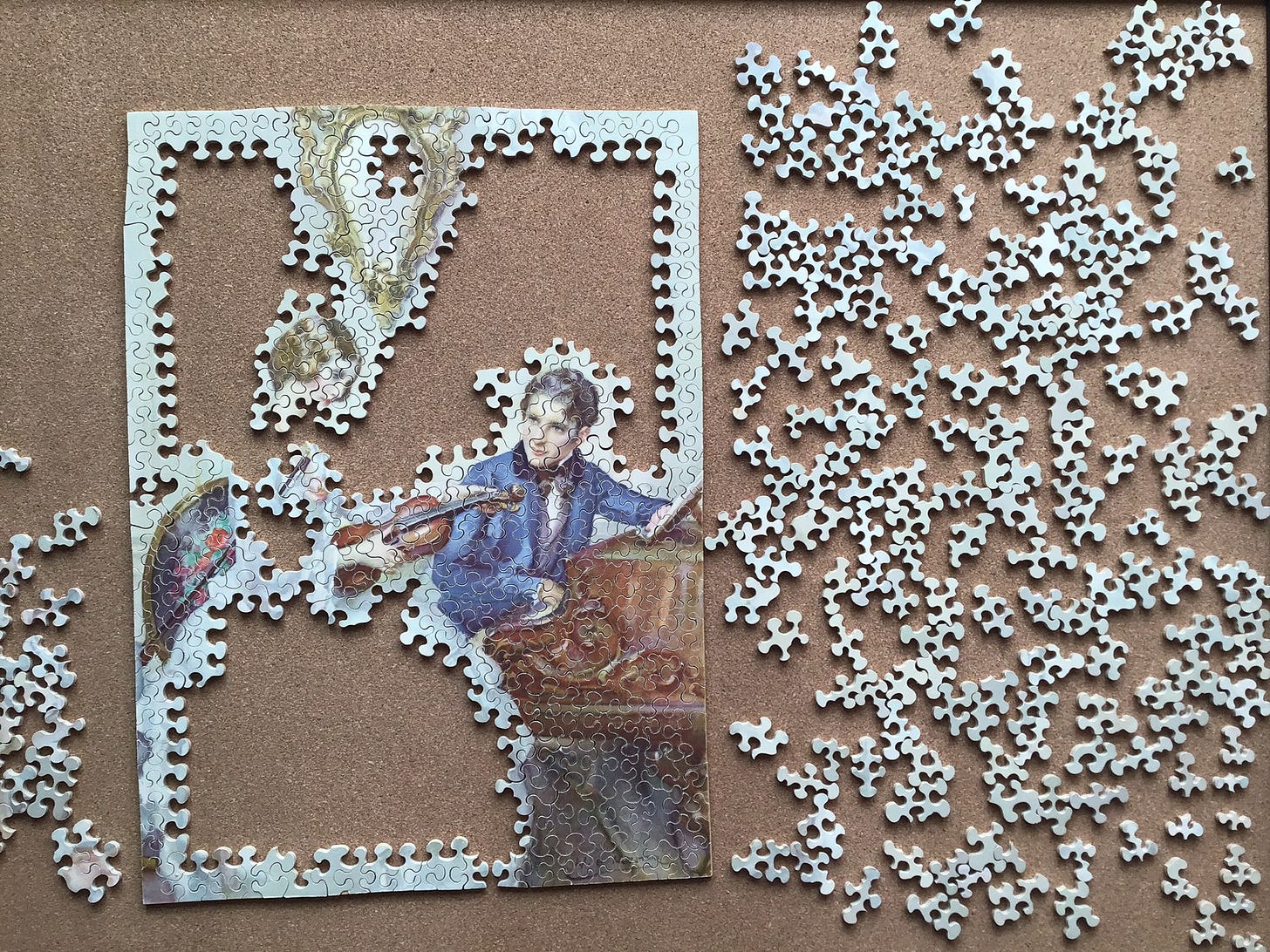

At this stage it was still a tough slog. I began to recognize why. The mirror and piano aren’t the only baroque elements in this puzzle. The cutting pattern has the perimeter of each piece almost entirely made up of knob type connectors of about the same size, giving the cutting a very complex, swirly, baroque feel. In my array of loose pieces the sharp outlines of the pieces visually dominated the gentle gradation of shades.

Running out of pieces with colour I turned to the edge pieces. There was no attempt to disguise them, and because of the swirly cutting pattern there were no false edges. Even so, the cacophony of connectors and having so many bluish-beige edge pieces to hunt through made completing the outside slow going.

The only pieces left that had any colour at all had tinges of very pale pink. I knew that was part of the dress. As I put them into place I became more and more aware that assembly was feeling tedious. I wasn’t having fun with this puzzle.

I counted the remaining beige pieces. There were 174 of them. In terms of number of pieces I was nearly 2/3 finished. But I knew that the tough time I had already been having was the easy part, with some colour differentiation to help me. In reality I figured that I was less than halfway there.

I knew that with time I probably could complete the puzzle by focusing on the dress first, and looking for connectors with slightly odd shapes or sizes. But I weighed the satisfaction that I would eventually feel from completing this VERY challenging puzzle against the long amount of time that tedious beige task would take. I decided to give up on assembling the puzzle.

In retrospect I don’t think that I made a mistake in choosing to buy this difficult puzzle. Actually, I think that the swirling baroque cutting pattern is both effective at making a challenging puzzle and suits the image. I will keep the puzzle to return to conquer it someday when my puzzling skills develop, but only when I feel that I am in the mood for a beige challenge. For now, my next puzzle will be VERY colourful.

Thank you for describing the process for cutting wooden puzzles and their popularity in the 1930s. Do you know if the folks who started their own one-person jigsaw businesses during the Depression would have used a treadle fret-saw or would they have had something powered by electricity then?

In the early 1930s two things happened - jigsaw puzzles became very fashionable and a lot of people were unemployed. As I understand it, most of the craftspeople who started jigsaw puzzle businesses in the 1930s were people who already had a scroll saw and skills from when that style of cutting was popular for architecture and cabinet-making. That would be mainly be in the Victorian era but continued up to about 1920. I think (but am not sure) that electric scroll saws were available but pricey by then but most of the puzzle-makers probably were using treadle machines. But I suspect a few inventive cutters may have modified their treadle machines by attaching a motor and a foot-powered speed controller (like the new-fangled electric sewing machines were beginning to have at that time.)

In fact, there are at least two puzzle-makers who still use old treadle scroll saws - Simon and Claudia Stocken (puzzleplex.co.uk) are the grandchildren of Enid Stocken, a renowned British cutter from the 1920s-'70s. The still make hand-cut jigsaw puzzles that feature their grandmother's old-school styles of cutting design and they make puzzles on old cast-iron treadle machines.