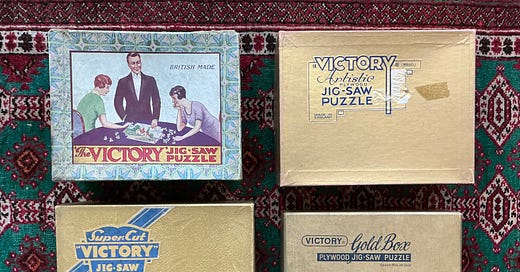

41. Vintage Victory puzzles - Part 1

First of a three-part series about the evolution of puzzles with figural pieces made by G.J. Hayter & Company from the late 1920s to the 1970s. (about 3600 words; 33 photos)

I have been on a vintage puzzle binge for the past several months. This three-part series is basically a continuation of my previous two-parter about the development vintage jigsaw puzzles without whimsies, except this one has puzzles that were made by just one manufacturer – G.J. Hayter & Company, Ltd. – and they are puzzles with figure pieces.

Part 1 (this part)

Introduction

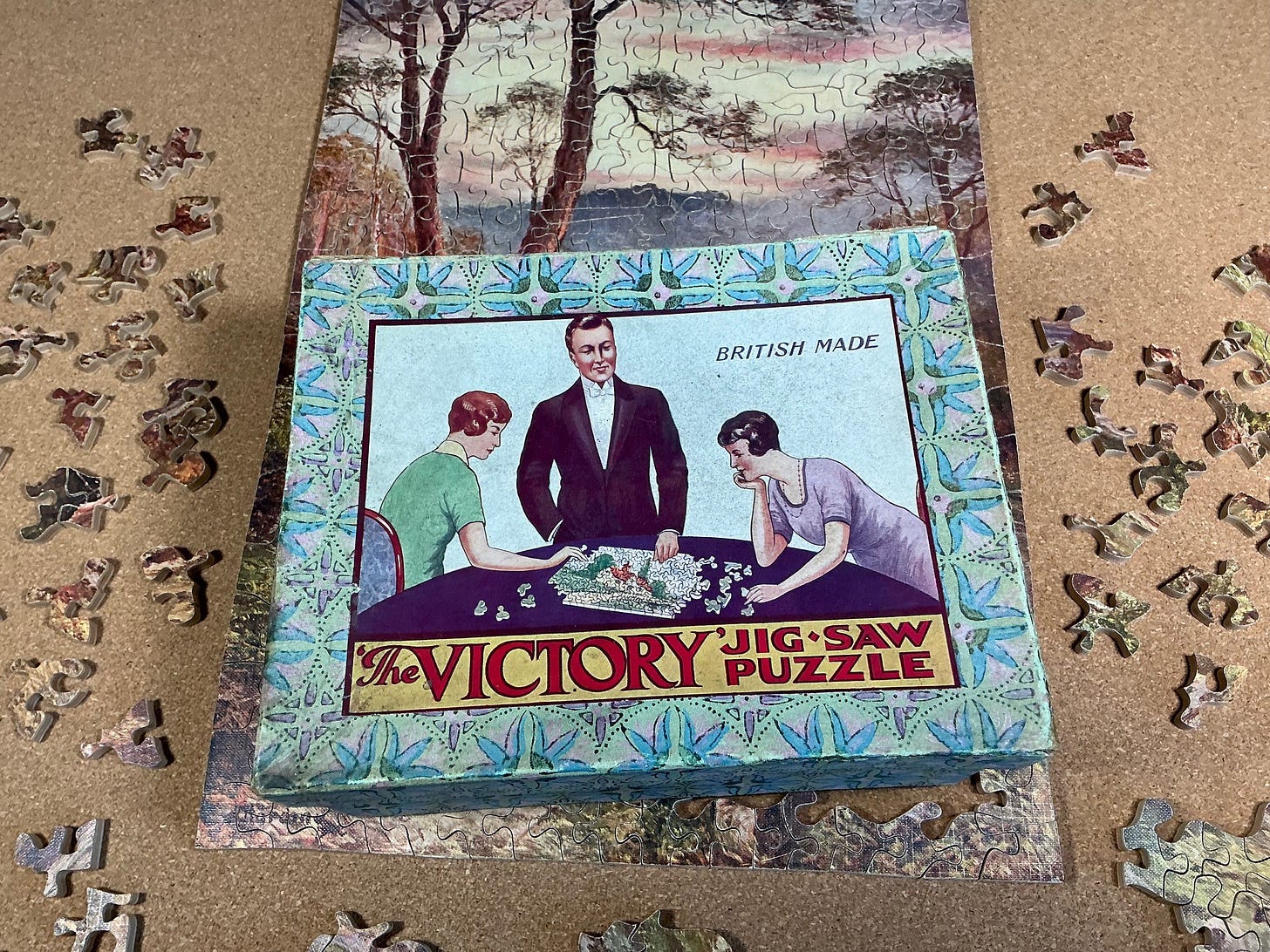

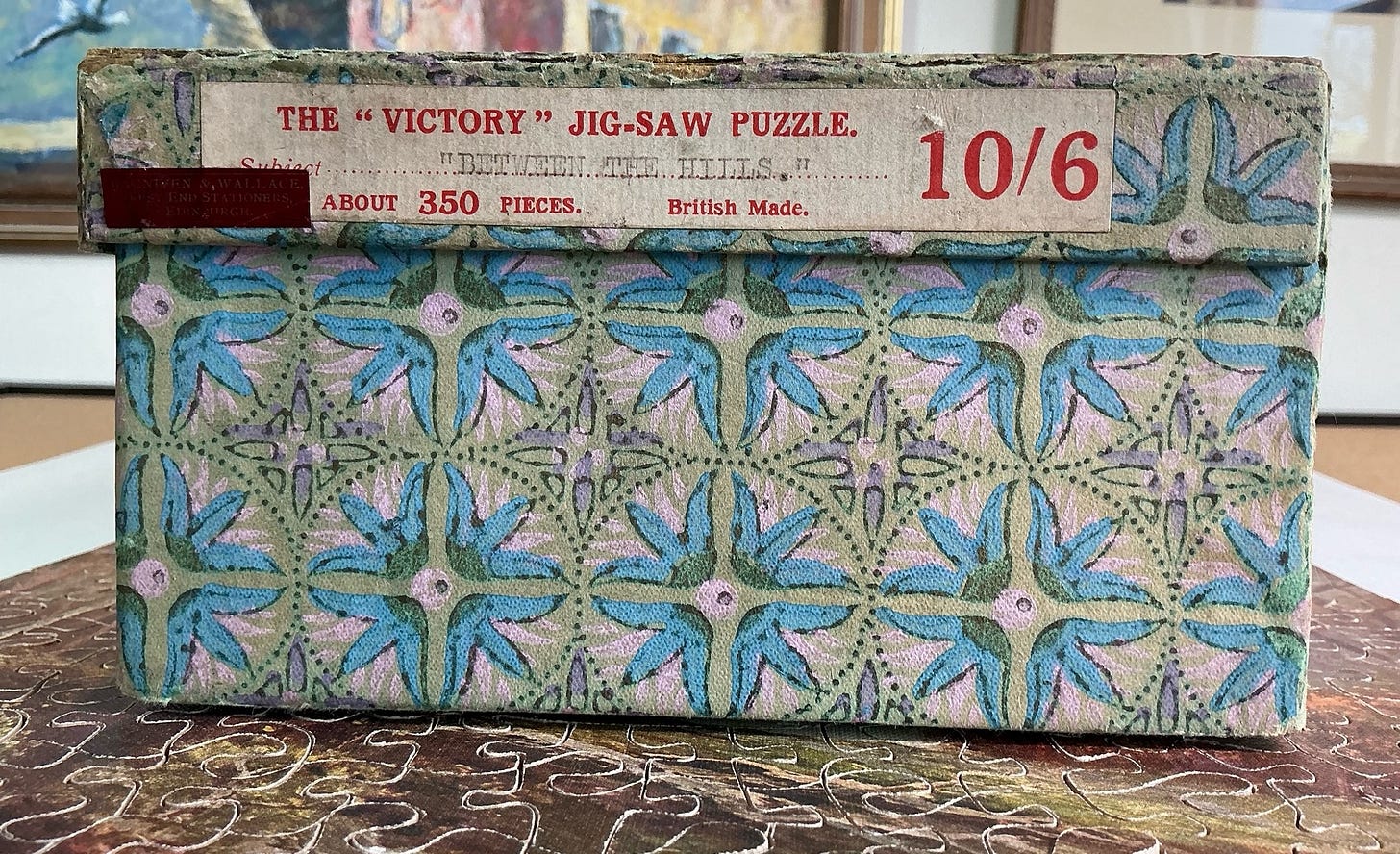

Between the Hills; “The Victory” puzzle made 1929

Jolly Good Old Ale; “The Victory” made ca. 1930(?)

Part 2

Caxton’s Workshops; Artistic series, made in the 1930s

Drawing the Covert; Super-Cut series, made in the 1930s

Part 3

Blossom Time; Artistic series, made ca. 1970

Jews House, Polperro; Gold Box (re-named Artistic series) made early 1970s

The Slave Market; Super-Cut series, made in the 1930s

Conclusions

Introduction

G.J. Hayter and Company Ltd., who made the original Victory brand of jigsaw puzzles, is well-known for making puzzles with figural pieces (AKA whimsies, figures or silhouettes.) But actually, over the company’s 70 or so years of existence they only made four series with that novelty feature – “The Victory”, Artistic, Super-Cut, and Gold Box (which was really just a re-branding of the Artistic series.) This is the first of three newsletters about those series. You can read about the history of the Hayter company in an essay specifically about that topic that I posted in this newsletter/blog in 2022, but I’ll give you a quick overview here.

Gerald Hayter began his jigsaw puzzle career as a Dorset teenager making push-fit puzzles with a hand fretsaw. He sold puzzles to friends in order to upgrade to a scroll saw. After he graduated from secondary school he moved to Bournemouth, and as a side gig to his £1 a week salary as a bank clerk he continued to make puzzles as an independent craftsman cutter. In about 1919, in honour of the Armistice after what was then called the Great War, Hayter decided to brand his puzzles as “The Victory” which later became just “Victory”.

Hayter kept up with the changing puzzle-cutting fashions which were evolving quickly at that time, making puzzles with interlocking pieces and figural pieces. His high quality puzzles became locally popular. Before long he began selling them to Beales, the largest department store in town, and trained his young wife (I don’t know her name) as his first assistant. You can tell that he already had big ambitions for his puzzle-making by the fact that he trademarked the Victory name and incorporated the business in 1927, naming it G.J. Hayter & Company Ltd. The next year he moved his workshop from a garden shed and their kitchen table to a rented workspace near the Bournemouth train station and trained more cutters. He still kept his day-job and his wife supervised production when he was at the bank.

In 1931, when the Great Depression was really taking hold, Gerald and his wife made a very brave decision: He quit his bank job and they bought an empty industrial building in the nearby suburb of Boscombe. This wasn’t just for more space to accommodate more employees: Hayter planned to change his whole business plan from being a craftsman’s workshop to factory manufacturing. As discussed briefly in my last newsletter, Hayter totally revamped his product line to enable him to compete against Britain’s other established puzzle manufacturers for the rapidly growing demand for jigsaw puzzles from working class people who were very price-sensitive.

After over a decade of exclusively making high-end artisan puzzles Hayter’s company began making Popular and Topical series puzzles. They had a fully interconnected, grid-style strip style of cutting with knob-style connectors. It was a supremely efficient cutting style that Hayter appears to have invented, and puzzles in those series did not have figural pieces. The pieces in such puzzles had the iconic four-sided shape of ones in most die-cut cardboard puzzles today.

Hayter’s grid cutting style was simple to learn and cut, and puzzles could be made fairly quickly by newly-trained hand-cutters. These bottom-of-the-line Victory puzzles were made with relatively thin 3 and 4 millimetre plywood and sold in boxes that had a picture of the complete puzzle on the box-top. In lieu of selling through a wholesaler Heyter “cut out the middle man” and marketed them directly to merchants. These inexpensive Victory wooden puzzles sold very well.

[Note: Die-cut cardboard puzzles were beginning to be made in the 1930, but hydrolic presses at that time were not strong so either only relatively small interlocking puzzles could be made in the 1930s or they had to be made with thin cardboard. Also the quality of cardboard was very poor back then compared to today. Therefore although cheap cardboard puzzles were available then their shoddy quality limited their appeal. This changed after WWII when stronger hydraulic presses that had been developed for war production became available and cardboard quality had improved.]

Hayter also simplified the cutting style of his previous higher quality puzzles that had been sold under “The Victory” brand (with quotation marks - see above photo) during his artisan workshop days. These premium grade Victory puzzles were sold in a series that was called “Artistic.” They used Hayter’s grid style of cutting whenever possible but included simple, sometimes even crude, whimsies. They were packaged in classy gold boxes without any cover pictures. Despite their higher prices the Artistic series puzzles also sold very well because they were among the least expensive jigsaws with figural pieces on the market in those days.

Sometime during the 1930s the company added a “new” product to its offerings but it was actually a return to making a variation on the high-calibre of puzzles that they had formerly been known for during the workshop days. These higher priced Super-Cut series puzzles were made by Hayter’s most talented and experienced cutters. They had better figural pieces than the Artistic series as well as other sophisticated cutting features such as a wavy outside edge and colour-line cutting to make them more challenging.

Other than that addition, the company’s products remained surprisingly unchanged for about 35 years as the company struggled to compete against the post-WWII rise of cardboard jigsaw puzzles. The images on the puzzles kept changing, following contemporary puzzle tastes, but the cutting styles and durability of the wood material remained the same. Thus, even Victory’s bottom-of-the-line Popular and Topical puzzles became premium puzzles when compared to cardboard.

In 1970, after over 50 years in business, Gerald Hayter was ready to retire. He sold the company to the established board game maker J.W. Spear & Sons (who owned the exclusive rights to produce and market the board game Scrabble outside of North America.)

The puzzles continued to be made in the factory that Hayter had founded in Bournemouth, and Spear continued using both the Victory Brand and the G.J. Hayter & Co. name, identified on the boxes initially as a subsidiary and later as a division of their own company. Within a few years Spear reorganized the company’s offerings, discontinuing the highest quality Super-Cut series and re-branding the Artistic series as “Gold Box” (which is probably what everyone had already been calling them.) Spear continued to make Victory puzzles until 1986 with (as we shall see) very little change from the company’s 50 year old house styles of cutting.

During the company’s long existence many, and perhaps most, of its jigsaw puzzles merely had strip grid-cutting with no whimsies, but it is the puzzles with figural pieces that this 3-part series will feature: These are the early 1920s workshop era “The Victory” ones, the 1930s and later Artistic and Super-Cut series, and finally the puzzles made in the company’s final years when the Spear company rebranded the old Artistic series as Gold Box.

I will present the puzzles in the chronological order in which I think they were made.

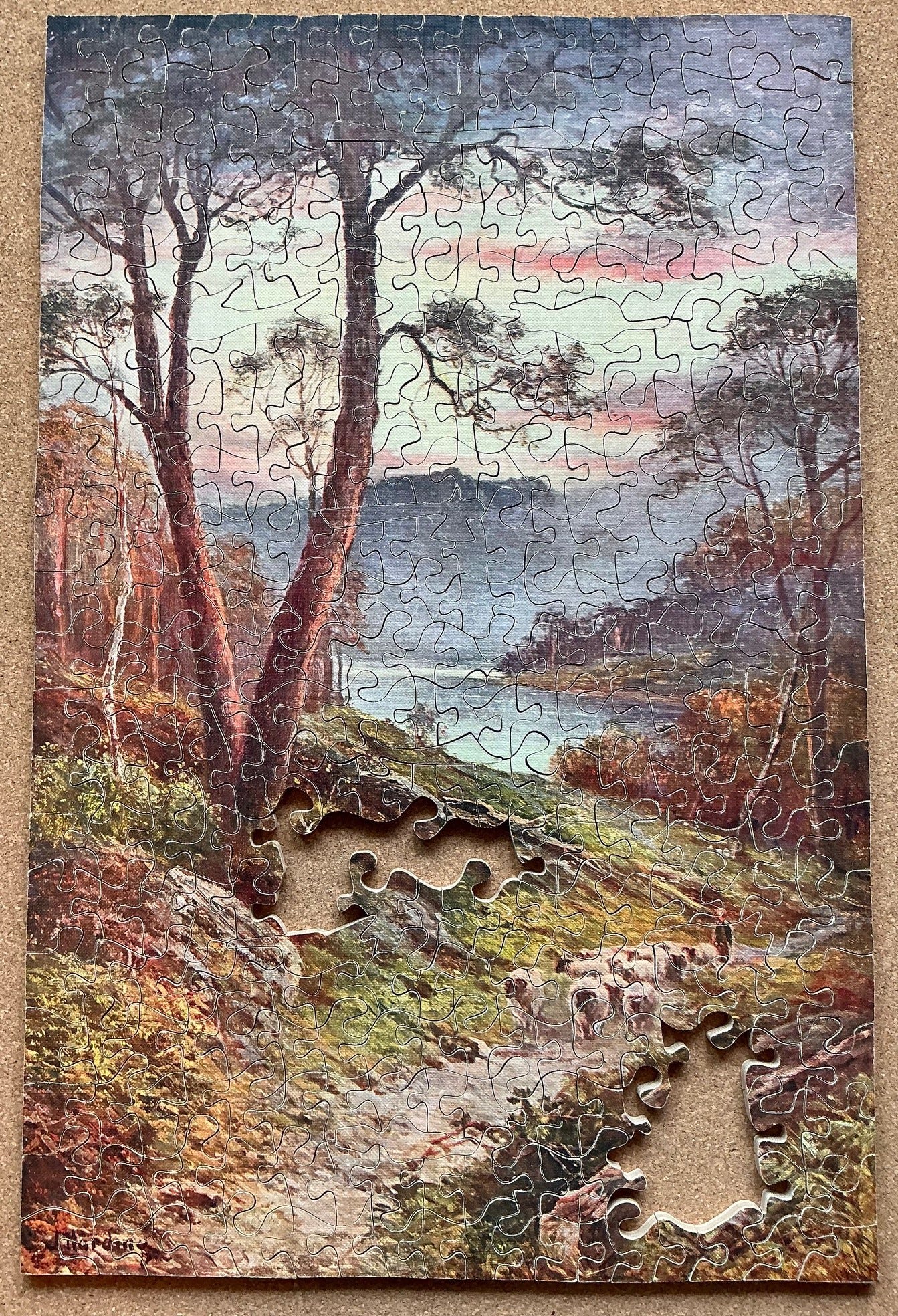

Between the Hills; “The Victory” made in 1929

maker – G.J. Hayter & Company, made in 1929

artist – not identified

about 350 pieces 17¾” x 11¾” (45 x 29.5 cm) average 3.8 cm²/piece 6mm 3ply

8 figural pieces; wave-like continuous horizontal cut-lines with “glides”;

fully interconnecting vertical cuts

I bought this 350 piece, quarter-inch thick puzzle for slightly less than £30 (about $50CDN or $40US.) That is considerably less than new comparable size laser-cut puzzles, meaning that even though it is high quality it fits into my idea of a “frugal alternative” category of wooden jigsaw puzzles. I think that it would have sold for more at auction if it didn’t have a landscape painting as its image: That style of artwork was once very popular but is now largely out-of-favour as puzzle images (except for impressionist paintings.) I would probably have gotten it for even less if the image did not include a shepherd herding sheep.

I suspect that I also benefitted from the fact that the vendor’s headline only listed this as a “Victory puzzle” leading many collectors not to look through the photos and see the distinctive box that indicates it was made the artisan workshop phase of Hayter’s career. As mentioned above, most Victory puzzles were originally marketed at a low price point and they were very popular, hence they are among the most common vintage wood puzzles to be found. In general, because of their abundance and simplicity (except for the Artistics and Super-Cuts) Victory’s factory-made puzzles do not have as much appeal for most collectors as puzzles from other vintage manufacturers, let alone ones made by highly-regarded independent hand-cutters.

But this 1920s style of packaging shows that this puzzle is from when Gerald Hayter’s Victory puzzles were still being made in his rented workshop near the Bournemouth train station and, as we will see, the company’s puzzles from that era were higher in quality than most of their later output. The puzzle appears in one of Hayter’s catalogs at the price of 10/6, which is how wood puzzle expert David Shearer was able to help me date it as being from 1929.

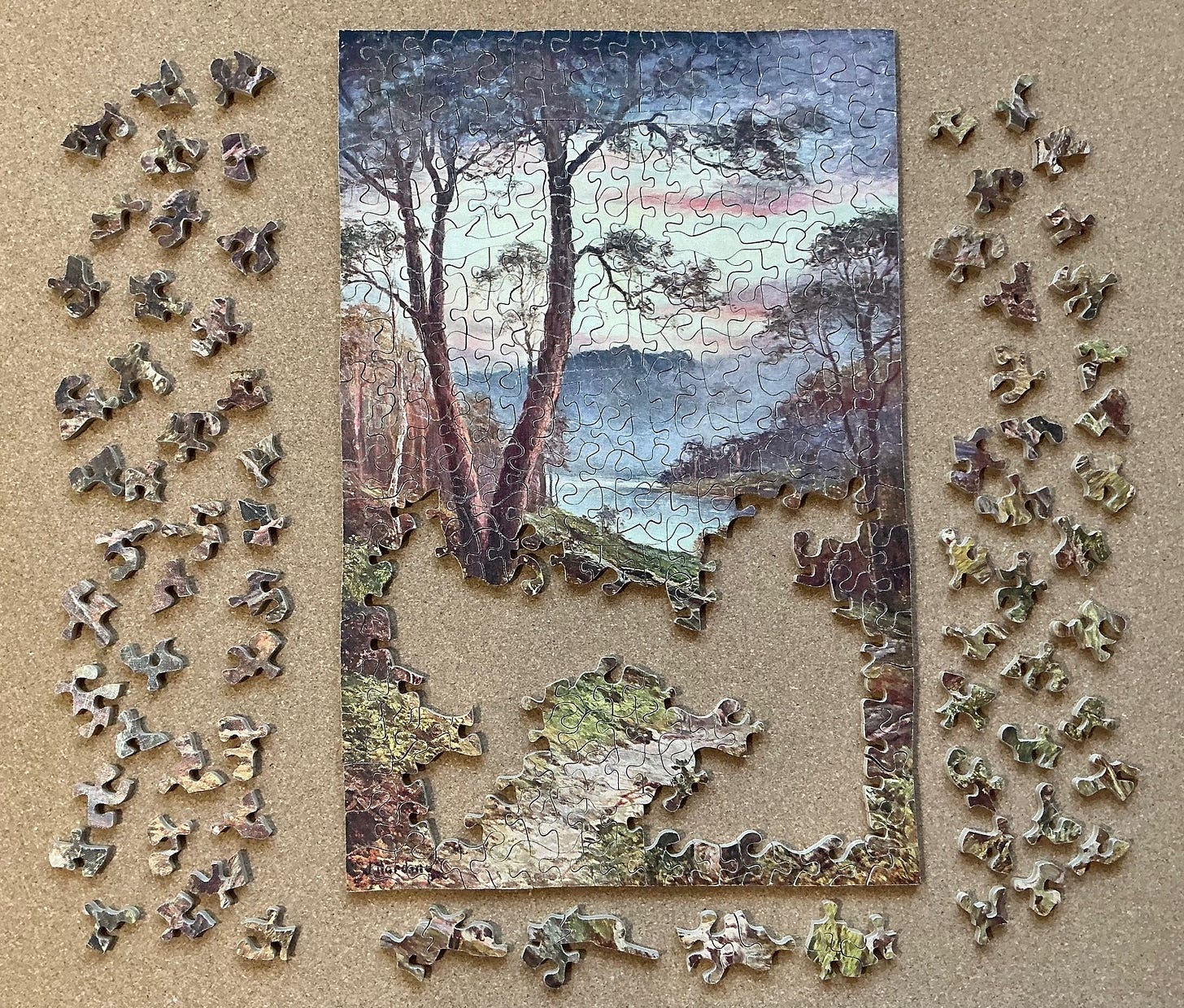

Here is how my assembly proceeded:

Since I remembered that this was a landscape picture I did not look for a focus of attention in the image. I began with the light-coloured sky pieces:

It wasn’t long before continuing with that approach got me to the left side-edge of the puzzle. I was surprised when following that edge upwards brought me to very dark pieces along the top where I expected to see more sky pieces. I was even more surprised when that top edge proved to be so short and I still a had a lot of pieces left. Obviously this landscape image is in portrait orientation. I had not remembered that oddity from when I bought it.

Up to this point, assembly had been going pretty easily because of the colour clues. But from here on it got a lot more challenging.

I was again surprised when the herd of sheep appeared along with their shepherd. They are such a small element in the picture that I had either not remembered them or had not noticed them when I bought the puzzle.

Tough slogging now, but never frustrating. Although the image is not especially to my tastes, the cutting design certainly is. It did not seem at all like a grid-cut Victory puzzle.

The cutting of this puzzle includes only eight very simple whimsies:

As I understand it, the cutters were given a minimum number of figural pieces that they had to cut into each size of puzzle, but they had considerable latitude as to which of the authorized template whimsy designs they could use as well as latitude as to where to place them. At Hayter & Co. they were not expected to match the whimsies thematically or in orientation to the image. In general, the workers chose ones that they could cut with minimal risk and expenditure of time. In this puzzle they are all in a horizontal orientation as if they are laying down rather than standing upright:

It was only after assembly when I was carefully studying the cutting design that I discerned the logic behind this placement. This is indeed grid-style strip cutting, but with the continuous side-to-side cut-lines done in what, to my eyes, is a rather elegant shape reminiscent of water waves (see photo below.) The upward-pointing connectors always lean to the right, and are spaced to provide some glides (i.e., periodically skipping the cutting of connectors.) The horizontally-oriented figure pieces minimally interfere with this continuous cutting. The overall effect is that the pieces do not seem at all like they were strip cut even though they had been.

Below is a photo of the only other “The Victory” puzzle in a 1920s-style box that I had done prior to Between the Hills, called Where the Garden and the River Meet. In fact, this is the puzzle that got me started on this vintage puzzle binge. Note that it has the same wave-like strip cutting, and that its whimsies are also oriented to maximize the number of potential continuous cut-lines, but the continuous cut-lines go up and down rather than from side to side.

There was one other feature that made Between the Hills stand out for me: The paper is embossed with a canvas-like texture. I have seen prints on paper like this before, but never as the image for a jigsaw puzzle, vintage or new. It makes this puzzle seem really classy.

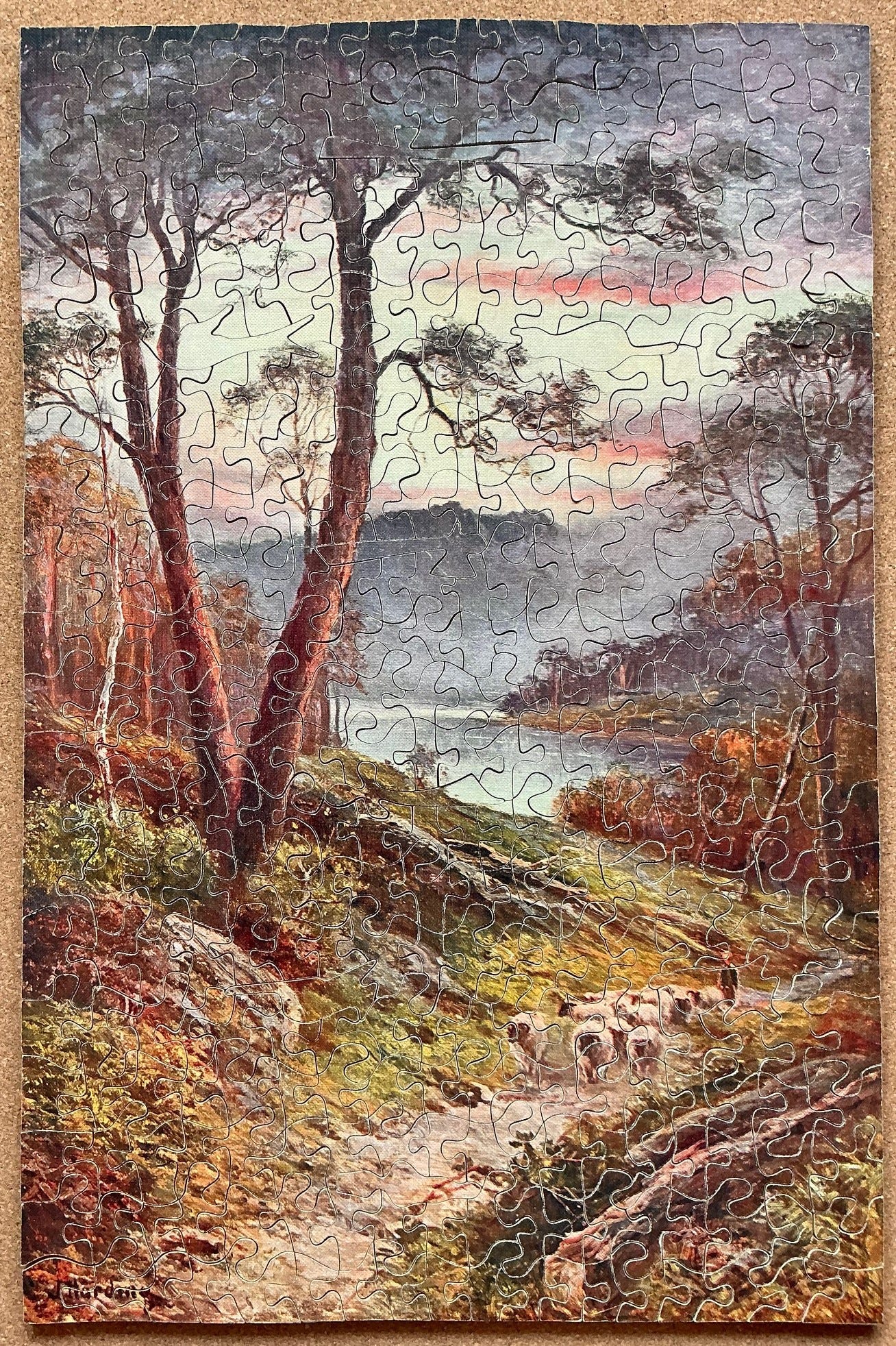

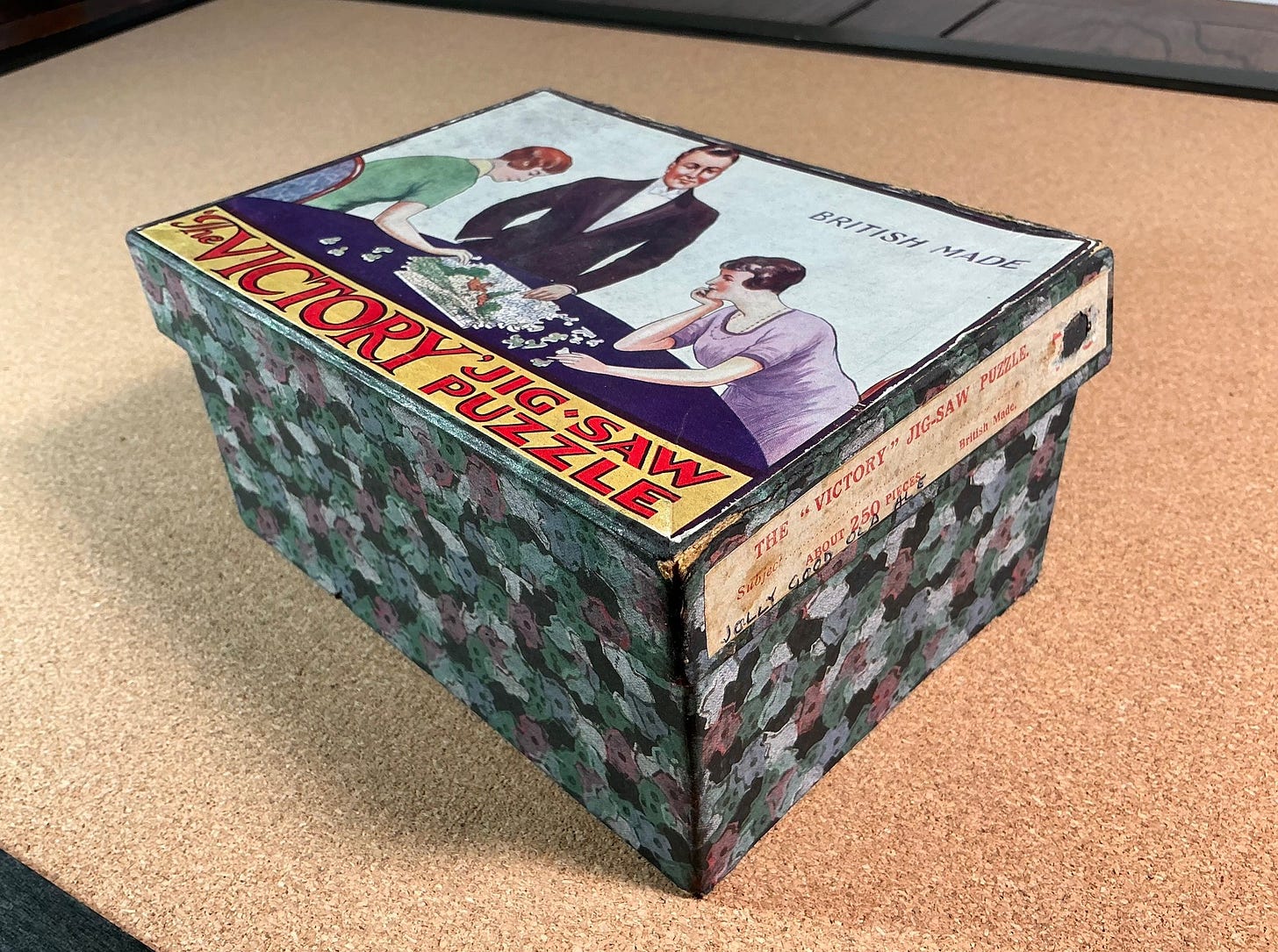

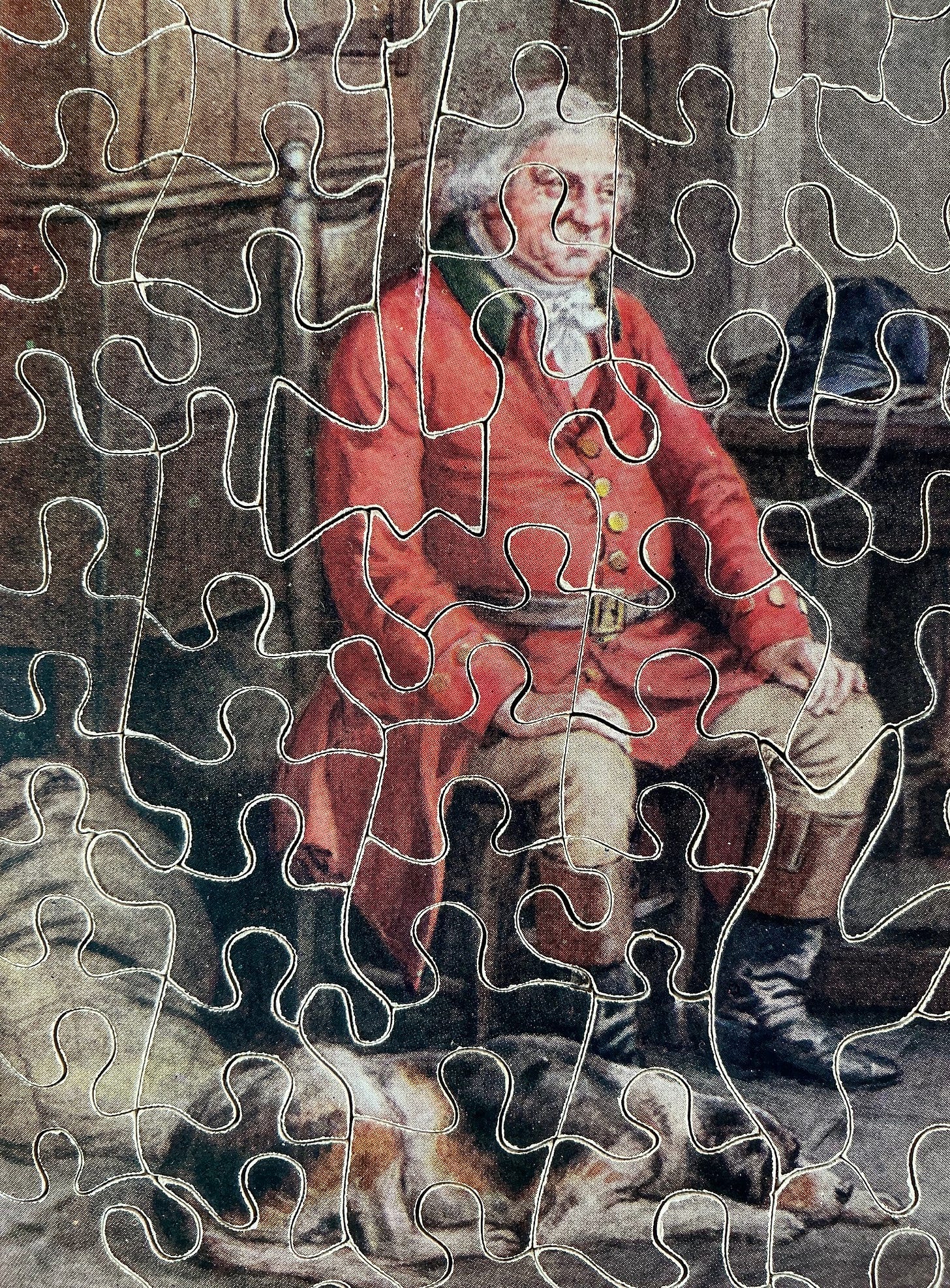

Jolly Good Old Ale; another “The Victory” puzzle

maker – G.J. Hayter & Company made in 1920s to very early ‘30s

artist – Frank Dadd (1851-1929)

about 350 pieces 17¾” x 11¾” (45 x 29.5 cm) average 3.8 cm²/piece 6mm 3ply

8 figural pieces; wave-like continuous horizontal cut-lines with glides;

fully interconnecting verticals

As you can see from this puzzle’s 1920s packaging this 250 piece puzzle is another one made during G.J. Hayter & Company’s craftsman workshop era. During that time they do not appear to have had separate series based on quality level. They did package lower piece-count puzzles with child-friendly images in boxes with a different 1920s-style artwork on the box-top in which the father is conspicuously absent:

During that time, when Gerald Hayter still had a day-job at the bank and his wife oversaw hired cutters during the day, the business plan seems to have been to make only high quality puzzles in accordance with Hayter’s house style of cutting. In the above 100-piece family-oriented puzzle the four figural pieces are placed to make a narrow line down the middle and five continuous cut-lines with connectors run parallel to them from top to bottom. In other words, it is essentially the same cutting design as Between the Hills and Where the Garden and River Meet except that there are no glides and the connectors stick out perpendicular to the continuous cut-lines instead of at an angle.

I found that Jolly Good Old Ale also follows this Victory house style. Before walking you through my assembly I’ll give you a sneak preview of its cutting style:

As you can see, the figural pieces are not placed randomly, but in such a way as to maximize the number of continuous vertical cut-lines. There are nine of them, with wave-like inclined connectors and glides. I didn’t know that this was a house style of cutting, at least for the latter 1920s, when I began assembly But I did look for the pattern because I had recognized it in the two other 1920s era “The Victory” puzzles I previously assembled, and had confirmed that this cutting was typical by checking the photos of other puzzles from that era on The Jigasaurus website.

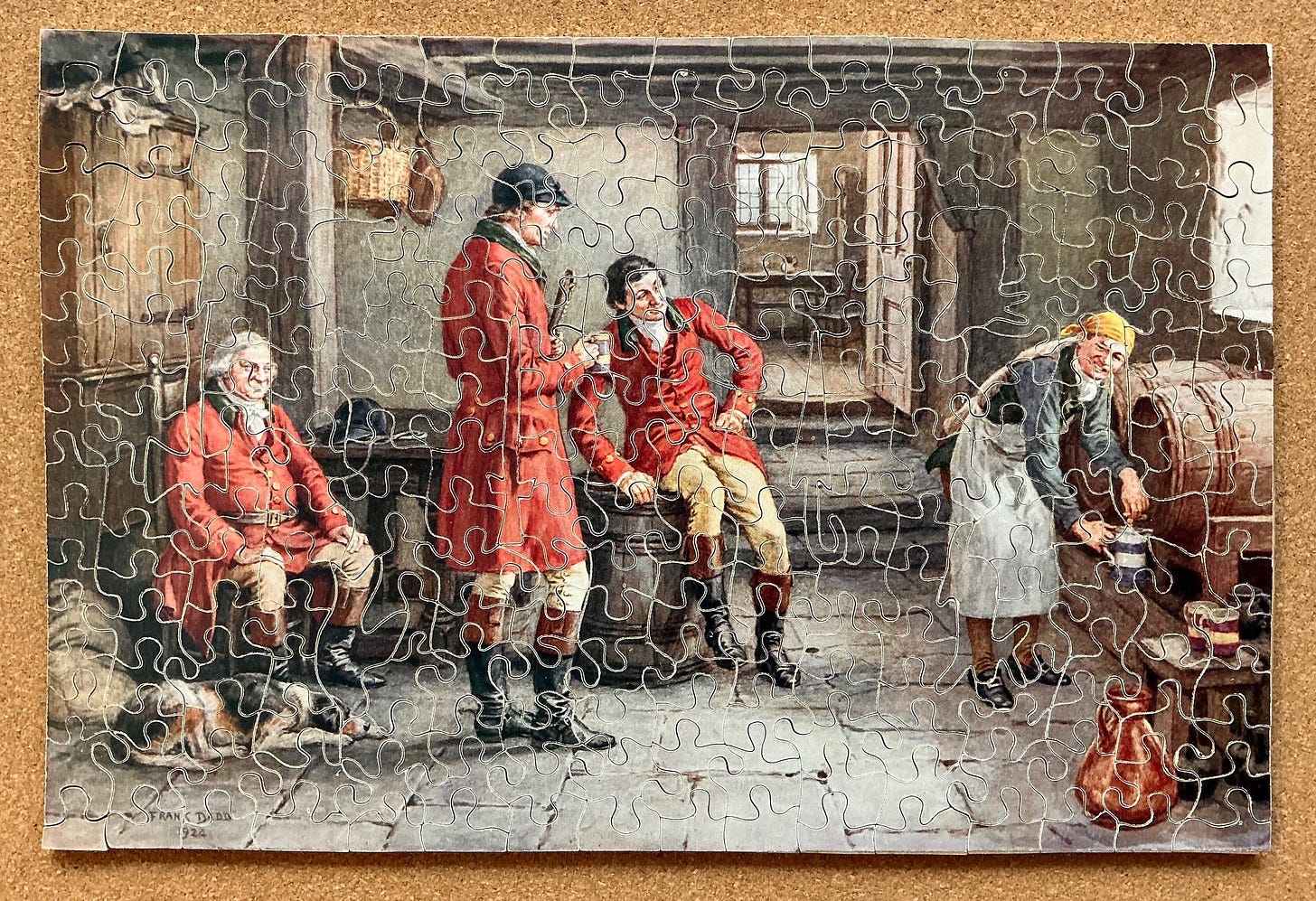

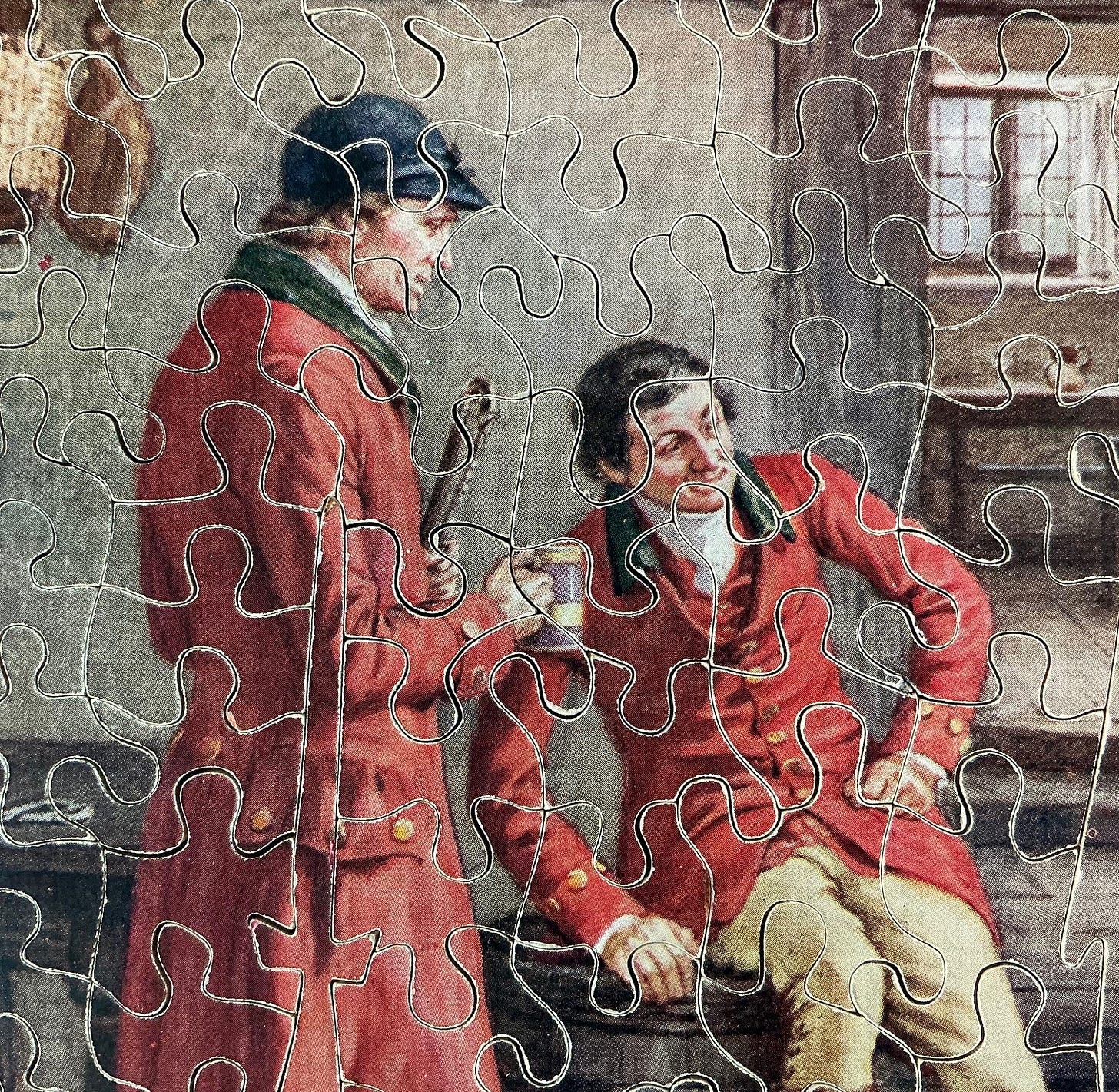

Since Jolly Good Old Ale is a relatively small puzzle I decided to do minimal sorting before beginning assembly. I had had a quick accidental glance at the image before I started and therefore knew that it featured three gentlemen in fox hunting attire apparently being served in a tavern by a serving wench. So the logical place to begin would be with those gentlemen. I selected out the pieces with red and what looked like clothes, hands and faces, as well as the figural pieces. There were also several apparent edge pieces that had dark parallel lines. I clustered those together too, but I did not bother to sort out other potential edge pieces at this stage.

The red pieces went together rather easily, with some help from two of the figure pieces. It looked like beginning assembly with a centre-of-attention strategy was going to work out well this time.

As I continued the fellows in red coats did look like they might be hunters resting after a fox hunt, but my remembered serving wench looked less like a wench and more like a pirate. I have often mentioned how my ability to forget is an asset for puzzle assembly. I can’t say the same thing for misremembering, which I am also quite good at. Perhaps someday I’ll find a puzzling use for that superpower too.

I next made progress growing the pirate/wench assembly island, which led me to doing white edge pieces, and then beginning a bottom edge sub-assembly.

I had reorganized my board to take the above photo and then focused on picture-taking. Right after I took it I realized that I could connect the sitting man on the left to the back of the man who is standing up, and that the white floor pieces could attach to the other seated gentleman’s boot. I love it when progress comes in a sudden burst like that!

Oops! I accidently deleted a progress photo here.

The fact that the portly seated gentleman has a hound resting beside him, and he is sitting in the only chair in the room, suggests to me that he is the lord of the manor. It was at this stage that I began to think of the setting for this image as being the ale storeroom of a manor house, and not a tavern. I also had to admit that the fellow tapping a tankard of ale is neither a wench nor a pirate, but probably a footman who had perhaps just returned from assisting on the hunt. He looks like he might be hoping that the master in a good mood and might let him have a taste of the jolly good old ale too. (There is an extra cup on the sideboard, just in case.)

[Digression: The young standing hunter already has a drink in hand. In such a circumstance I wonder if proper protocol would be for a servant to serve the master first, or to serve the guests first? If it is the former then my speculation abut the older seated gentleman being the master of the house would be incorrect.]

Next is the traditional edges-are-complete celebratory photo. About here I was absolutely convinced that there were some pieces missing from my puzzle. I thought I knew exactly what shapes were needed from the loose pieces to fill some of the voids, but couldn’t find them. I checked the box; no pieces there. In other words, the situation was totally normal for me at this stage of assembly. I wonder if knowing that pieces are missing, and at the same time knowing that I am wrong, might be another puzzling superpower for which I will someday find a use? But that doesn’t seem too likely.

I had recognized about halfway through assembly that this cutting design is indeed what I now think was Hayter’s house style for puzzles with whimsies during the late 1920s. But knowing that any glides would go up and down, and that the connectors from the vertical cuts would go out obliquely from the cut, while the pieces in which the connectors stick out straight, did not help me much until I got to this very final stage …

… when those last few pieces did go in very quickly:

Putting together a jigsaw puzzle draws assemblers’ attention to little details in the image, and this one was a real treat in that regard. Scenes of the gentry in fox hunting attire are quite common in vintage British jigsaws because they were a popular subject in British 18th and 19th century paintings. They are a subset of genre paintings, which are nostalgic depictions of aspects of everyday life in which ordinary people engage in common activities.

I especially like the depictions of the people and the dog in this puzzle. The hound looks very tired, reinforcing my impression that this scene is taking place after the hunt, not before it.

The artist is Frank Dadd (1851-1929.) According to artnet:

Frank Dadd was born on the 28th March 1851 in London. He studied at the Royal College of Art and at the Royal Academy Schools, where he won a Silver medal for drawing from life. He commenced black and white work in about 1882 and worked as an illustrator for the Illustrated London News from 1878-1884 and then at The Graphic.

He specialised in historical and genre paintings, and in addition illustrated several books …

He was honoured to have his paintings chosen for exhibition at the Royal Academy from 1878. He was elected to the Royal Institute of Painters in Water-colours in 1884 and the Royal Institute of Oil Painters in 1888.

He lived at Wallington in Surrey and later at Teignmouth in Devon where he died on 7th March 1929.

Coming up: Part 2 has a puzzle from Hayter’s popular Artistic series and one from the company’s highest-quality Super-Cut series, both made in the 1930s. Part 3 will have another Super-Cut, and one from near the end the Artistic series as well as one from near the beginning of the Gold Box series, both made in the early 1970s.

Thank you, Bill, for another richly informational essay.

Meaning to be helpful (not nit-picky). I'll mention to you that you posted your earlier essay about the Hayter company in 2022, not 1922—you may want to correct that date.

I always get a kick out of reading about the home-based settings of some of the really excellent puzzle-making—in this case, I see, in my mind's eye, Hayter's craft work being done in a garden shed and at a kitchen table even before official business incorporation!

Good to read about Hayter's "inventions" that came before he got into figural pieces. "Between the Hills," which does include eight figurals, is a particularly lovely puzzle. It's interesting to me that, during assembly, you were able to figure out the placement logic for those eight. I don't guess that it would have occurred to me to notice that; but, of course, you are passionate about all aspects of your wooden-puzzle hobby. Surmising that the scene in "Jolly Good Ale" comes after, rather than before the hunt, and also that the serving of ale is likely taking place in a manor house, rather than in a tavern—these are also nice points, Bill.

Always a good read . I have a large collection of the GJ Hayter wood Jigsaws Thanks Barbara Tapp