38. "Newer" vintage Victory puzzles – London landmarks

Reports on two puzzles from the G.J. Hayter's Victory brand's later years, updated and expanded from my 2022 postings about them on Facebook. (about 5300 words; 32 pictures)

This is the first of two postings about vintage Victory jigsaw puzzles. After a new introduction and a brief new essay about buying used puzzles online, my reports on these two puzzles are basically edited and updated versions of messages I posted in 2022 in the Wooden Jigsaw Puzzle Club discussion group on Facebook. As with my other retro-reviews I am re-posting here so that there will be a more permanent and accessible record of my reaction to the puzzles and my research related to them.

Introduction about the Hayter company

Both of these puzzles were manufactured by G. J. Hayter & Co. Ltd in that company’s later years. Gerald Hayter made the Victory brand of wood puzzles from about 1919 to the late 1980s. In the 1930s its “Puzzle Works” in Bournemouth, England was the largest jigsaw puzzle factory in the world. Based on number of employees it is still the largest and longest-lasting wooden jigsaw puzzle company there has ever been.

Because of the sheer volume of Victory puzzles that were made in Britain at that time they are among the vintage puzzles that are most frequently available today. While the ones from the company’s “Super-cut” premium line are considered highly collectable, the others tend to sell for relatively modest prices.

As far as I can tell, Gerald Hayter may not have been the first entrepreneur to apply an assembly-line style of manufacturing efficiency to puzzle-making, as well as the one who invented the efficient grid cutting method. The style became a distinctive characteristic of all of his company’s puzzles except for his most expensive “Super-Cut” premium series.

Fully-interlocking jigsaw puzzles had emerged as the preferred style of puzzle shortly after it was introduced in the late 1920s and all of the manufacturers that emerged during the Great Depression’s “golden age of jigsaw puzzles” made fully interlocking puzzles using various distinctive styles of cutting. But Hayter’s grid cutting is the one that could be done most quickly and reliably by less-experienced or less-skilled cutters. Less cutting time meant lower cost, so they could be sold for a lower price than those made by the other puzzle factories

Ignoring the connectors, the horizontal and vertical grid cuts can be straight, curved or wandering but except when connectors are skipped it results in the distinctive four-sided pieces with an “innie” or “outie” knob connector on each side. Such pieces, with a straight line and connectors on every side have become emblematic of all jigsaw puzzles. That is because the same style is nearly ubiquitous for cardboard jigsaw puzzles (more about that below under Houses of Parliament.) Perhaps because of the iconic nature of the pieces, grid cutting continues to be used in making many wood puzzles today (especially in Britain) despite the fact that such efficiency is less important in the age of laser-cutting.

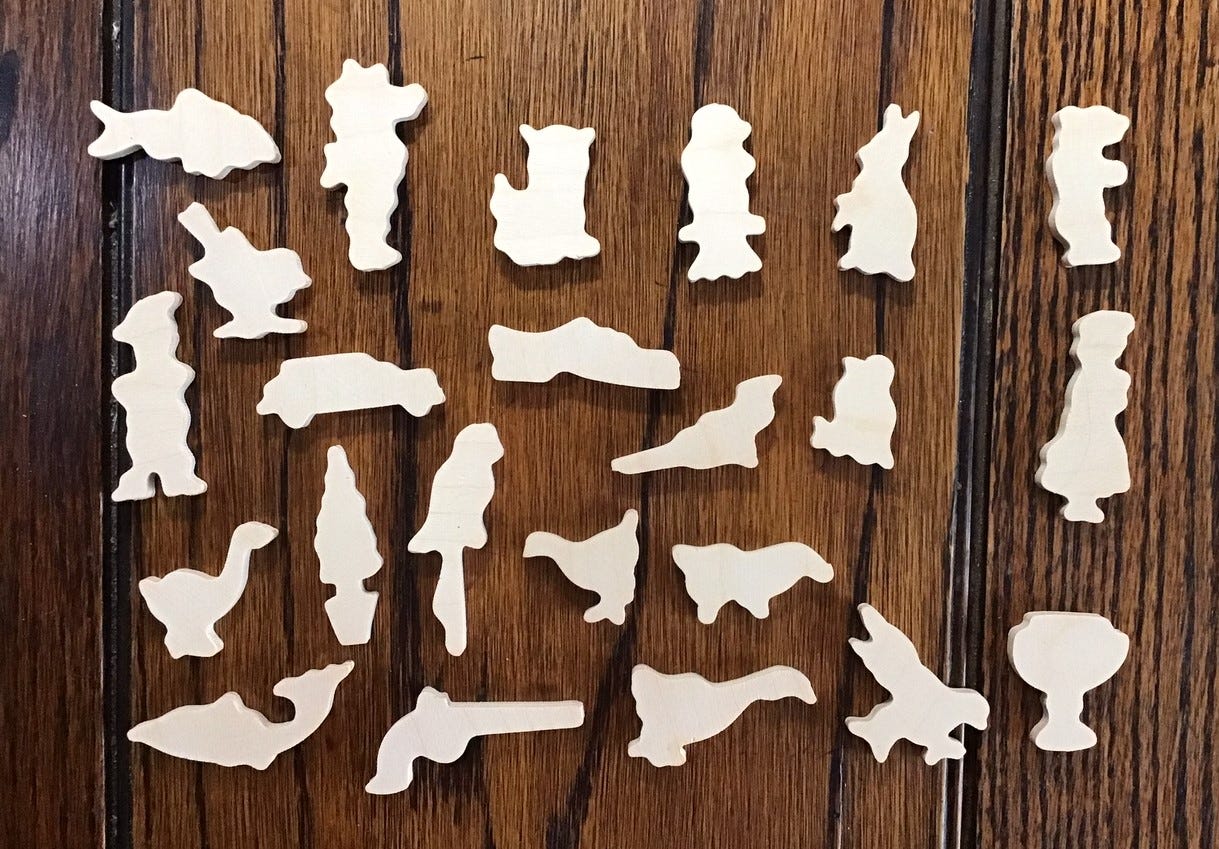

Hayter’s company was also a leader among the manufacturers (as distinct from the many artisan workshops that also operated during the Great Depression) in using figural pieces in its puzzles. The whimsies in Hayter’s gold boxed Victory puzzles were usually scattered within a matrix of grid-cut background pieces.

These two puzzles were made during the latter years of G.J. Hayter’s long career, during a time when the inexpensive cardboard puzzles dominated the marketplace. Wooden puzzles were still made by artisan craftspeople, and for children in factories, but in the 1960s and ‘70s all of the other puzzle-making had stopped making wooden jigsaw puzzles for adults.

The British wooden puzzle-makers had converted to wartime production during WWII and they faced a tough challenge getting back into puzzle-making when the war was over due to the rise in popularity of the much less expensive cardboard puzzles. Cardboard puzzles had been made as early as the 1930s the material’s poor quality at that time had limited their popularity. The technology of die-cutting puzzles has not changed much in the interim but the quality of cardboard had greatly improved.

In the postwar era, wooden jigsaw puzzles were still being made by individual craftspeople in small workshops but the other manufacturers’ attempts to revive their puzzle lines were short-lived and the former industry leader and sole surviving factory, G.J. Hayter & Co., struggled along and was a pale shadow of its former glory. Interestingly, none of the former wood puzzle-makers converted to die-cutting cardboard.

In 1970 Gerald Hayter retired and sold the business to the toymaker Spear & Sons. They kept it going in Bournemouth as a division of their own company until 1988 when the Puzzle Works” was closed for good.

For more information about G.J. Hayter and his company see this essay that I wrote about their history. Here are essays about two other vintage Victory puzzles. This posting I wrote about the recently re-established Victory brand (under different ownership but also with roots in Bournemouth) also includes additional information about the earlier company.

Buying vintage wooden jigsaw puzzles

I recognized early on after discovering wood jigsaw puzzles that at the pace I was assembling them I would need to find a strategy to make my new hobby more affordable. My first attempt was to alternate wood with cardboard. Cardboard jigsaw puzzles are cheap, but the experience also feels that way compared to wood. I then tried to alternate premium quality 5 and 6 millimetre thick puzzles with the inexpensive made-in-China 3 mm thick ones that are readily available online. That was better than cardboard but I still missed the luxurious look and feel of the premium puzzles. I then noticed that used vintage wooden puzzles are also available fairly inexpensively online, especially from British eBay auctions.

Buying used vintage wooden puzzles, especially those that were factory-made in the 1930s, when literally millions of them were made every week, can often represent a less-expensive alternative to buying newly-made laser- or hand-cut jigsaw puzzles. Admittedly, printing technology has improved greatly since then so the colours will generally not be as vibrant as today’s puzzles. Also, the puzzles’ images may seem quite dated in the context of modern sensibilities. Add to that, factory hand-cut puzzles do not have the intricate whimsies that we have come to expect in laser-cut puzzles, and

On the other hand, remember that these are hand cut puzzles at astonishingly low prices for that format. And I have learned that puzzles with artwork that is unfashionable these days often sell for especially low prices at auction. The tactile feeling of their thick wood is as rich as todays premium-quality laser-cut wooden puzzles, and they have their own intangible benefits as an experience of rootedness experiencing history that comes from assembling puzzles made so long ago. That comes in spite of, or perhaps because of, the patina of edge wear that pieces may have, and the fact that many of them have out-of-style artwork.

On balance, I think that I still prefer high-quality new puzzles because of their vibrant colours and the fact that modern cutting designers are standing on the shoulders of giants, but vintage hand-cut puzzles have become my favourite “frugal alternatives.”

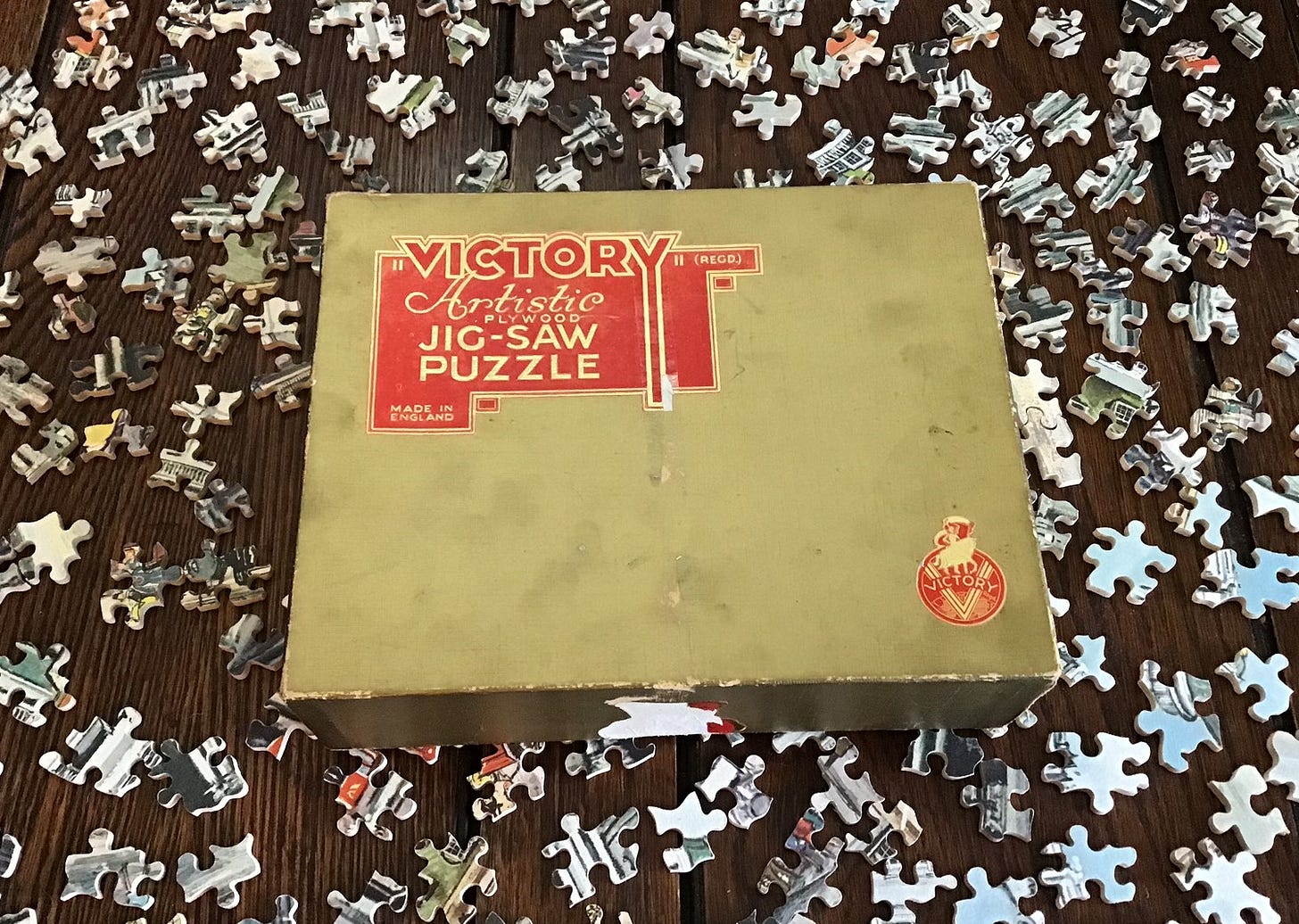

My first step in learning that came from buying St. Pauls (London Scene) as an experiment. It was my first vintage puzzle, and the first time that I bought anything from an online auction. In February 2022 it cost £41 ($49 USD or $63 CAN at the time.) The cost of shipping brought that up to $70USD (about $90CAN), which is quite a bit less expensive than a newly-made laser-cut puzzle of the same size.

I didn’t know it then but that auction price is somewhat more pricy than average for a 400 piece vintage Victory puzzle, probably because its artwork is more in tune to modern tastes than many vintage puzzles. I bought Houses of Parliament shortly thereafter for only £17 (about $20 USD or $26 CAN). That is much cheaper than today’s comparable laser-cut puzzles, and even the Chinese-made 3mm ones. But then, it is from the Hayter company’s less expensive “Popular” product line which are only 4 mm thick and it which do not include the figural pieces that may people want/expect from wood puzzles these days. So, a good tip for making a wooden puzzle hobby less expensive is to developing a taste for puzzles that do not have whimsies and which have out-of-fashion images.

Puzzles that are incomplete should be much, much less expensive than complete ones and even my desire for frugality doesn’t go that far. Unless you are willing to take your chances only buy puzzles that are identified as being complete, or better yet, which includes a photograph of the complete puzzle. In general, if the vendor has assembled the puzzle the posting will include at least one photo of it as complete.

Also, zoom in on photos to see the condition of the pieces. Vintage puzzles can have damage, and were printed on paper that was affixed to wood which sometimes become torn off. I haven’t encountered this problem yet but if an old puzzle was stored in damp conditions it may have mildew damage or an unpleasant odor. In my experience, vendors are good about answering questions posed to them through the auction or marketplace website.

Another good tip is to buy from vendors who are willing to hold puzzles until you have bought enough for a combined shipment, and who are willing ship by regular mail. Ask before you bid - some will and some won’t. I have been buying my puzzles from vendors who specialize in selling vintage jigsaw puzzles, or at least frequently offer such puzzles for sale. (On eBay, you can click on the vendor’s ID to see what other merchandise they have for sale.) The minimum basic charge of mail delivery of a parcel from Britain to Canada for example, is the same for any shipment up to two kilos. The price is £30, with tracking and insurance, and expect up to two weeks for delivery. But for that cost you can ship multiple wood puzzles adding up to more than 1000 pieces.

eBay’s default international shipping option gives very quick delivery but it is very expensive. I won’t get into my rant about it now but I personally find that shipping by mail is slower but much less expensive. Again, if the for-sale posting is defaulted to eBay’s international shipping you can ask if the vendor would be willing to ship by mail, and again, some will and some won’t.

Now, on to my retro-reviews:

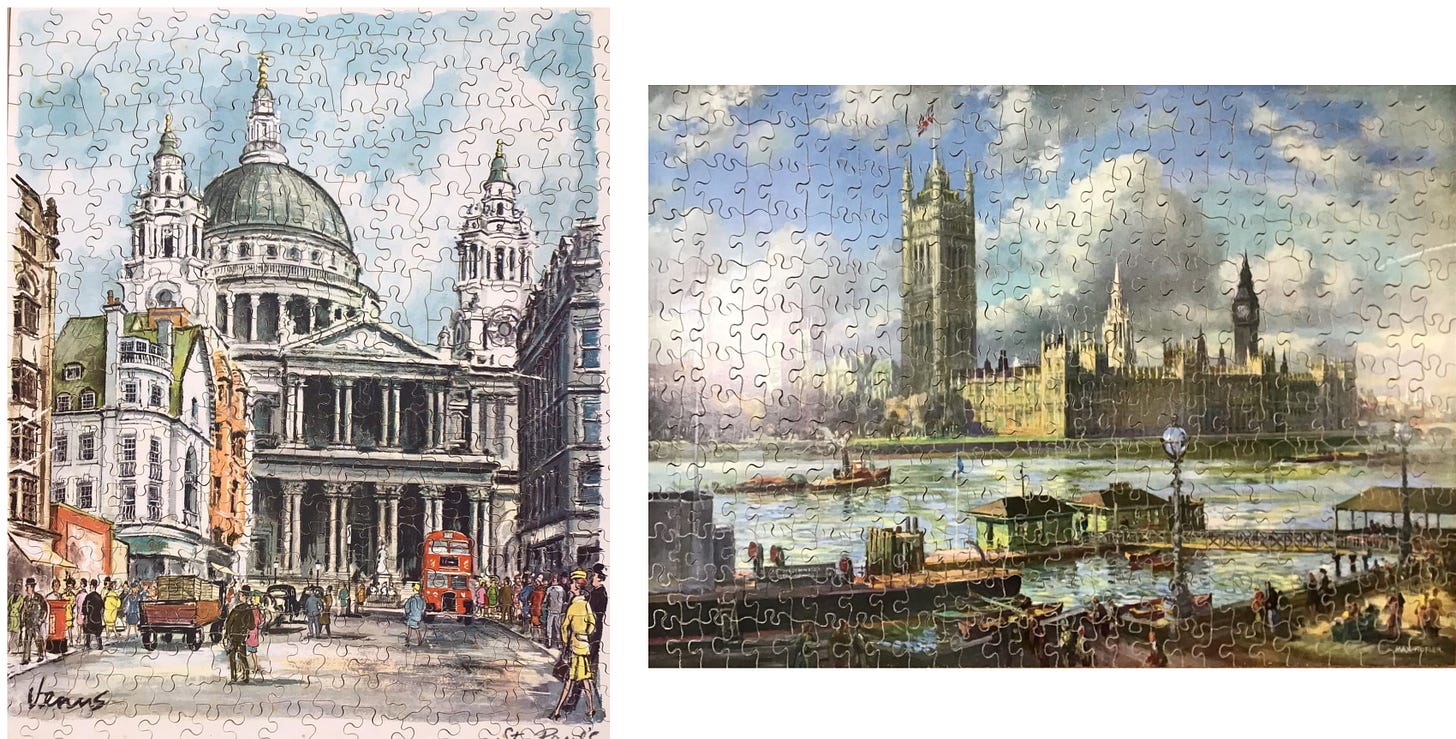

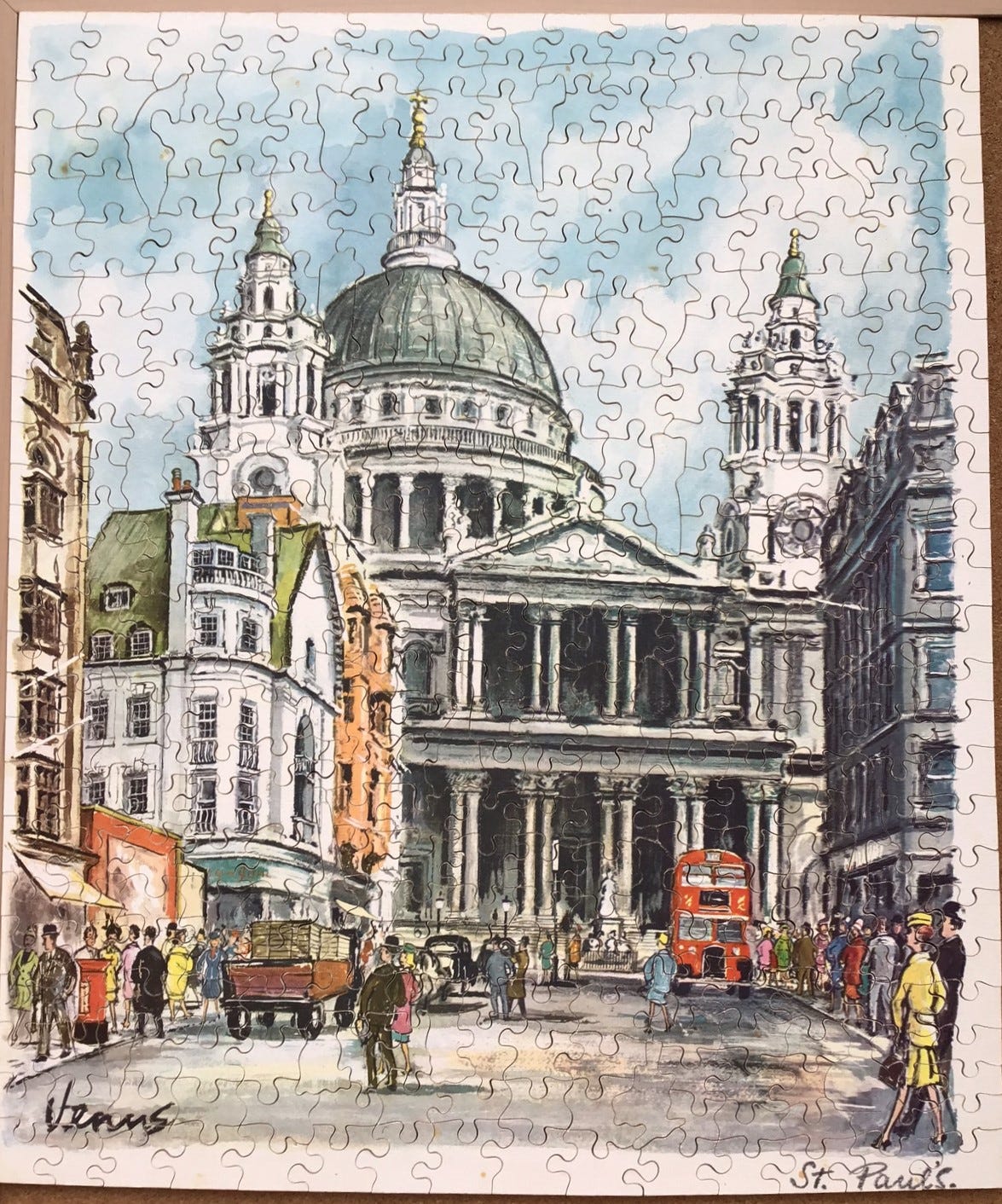

St. Pauls (London Scene)

I bought this puzzle in February 2022, less than a month after I had begun my new wooden jigsaw puzzles hobby. I assembled it in March and by then had already become an enthusiastic participant in the international Wooden Jigsaw Puzzle Club discussion group on Facebook. I was so excited about doing my first hand-cut puzzle, and first vintage one, that I decided to tell others about it in progress report format. These are edited and updated versions of the progress reports I posted there while assembling this puzzle.

First St Paul’s posting – March 18

After completing an inexpensive Chinese puzzle a few days ago, yesterday evening I began rebalancing my puzzling yin and yang by beginning my first hand cut one. But sticking with the “frugal options” theme this puzzle is a used 400 piece vintage Victory puzzle that I bought from an American eBay seller. I was so excited about doing a hand-cut puzzle that it jumped to the front of my assembly queue.

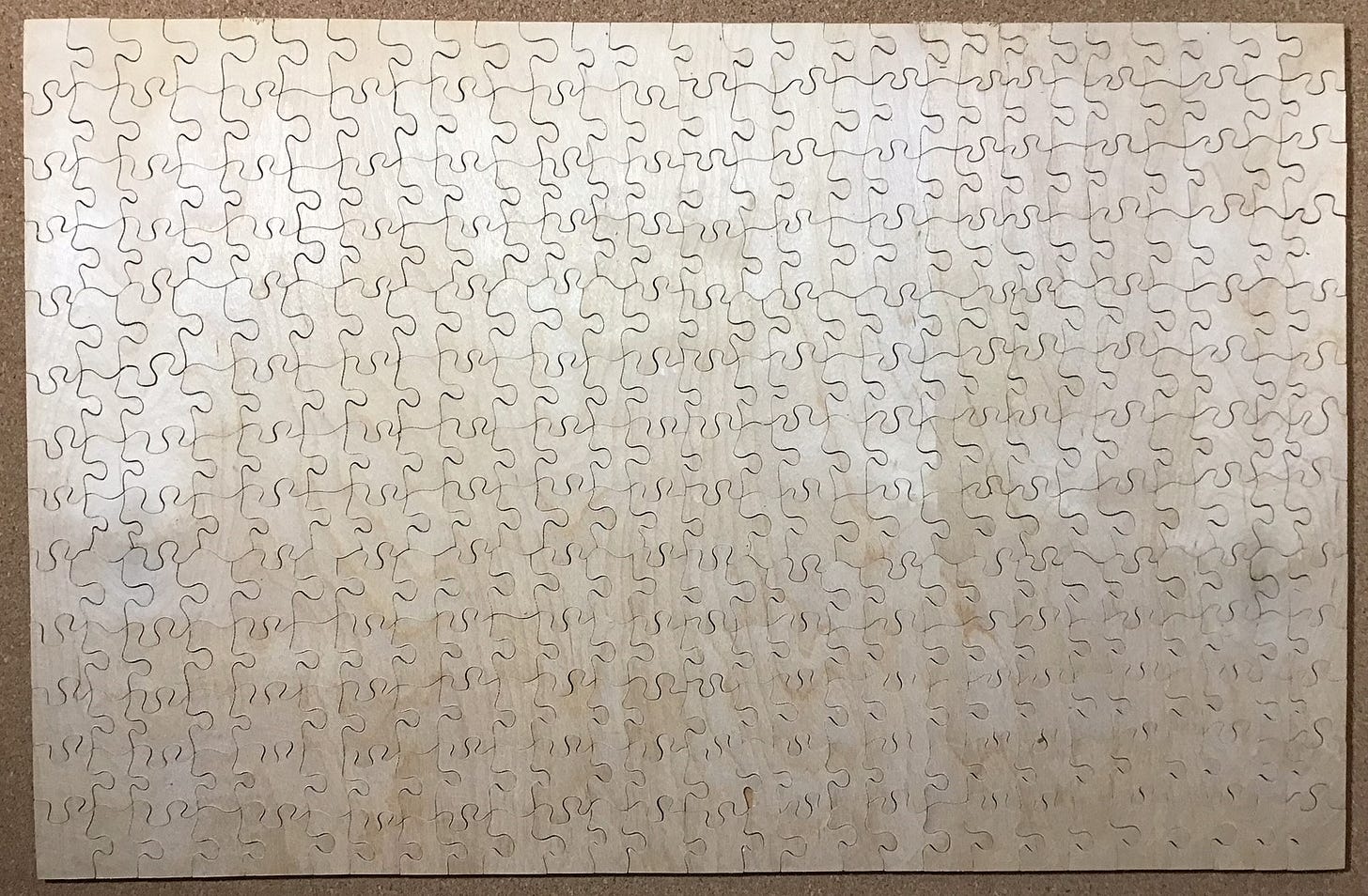

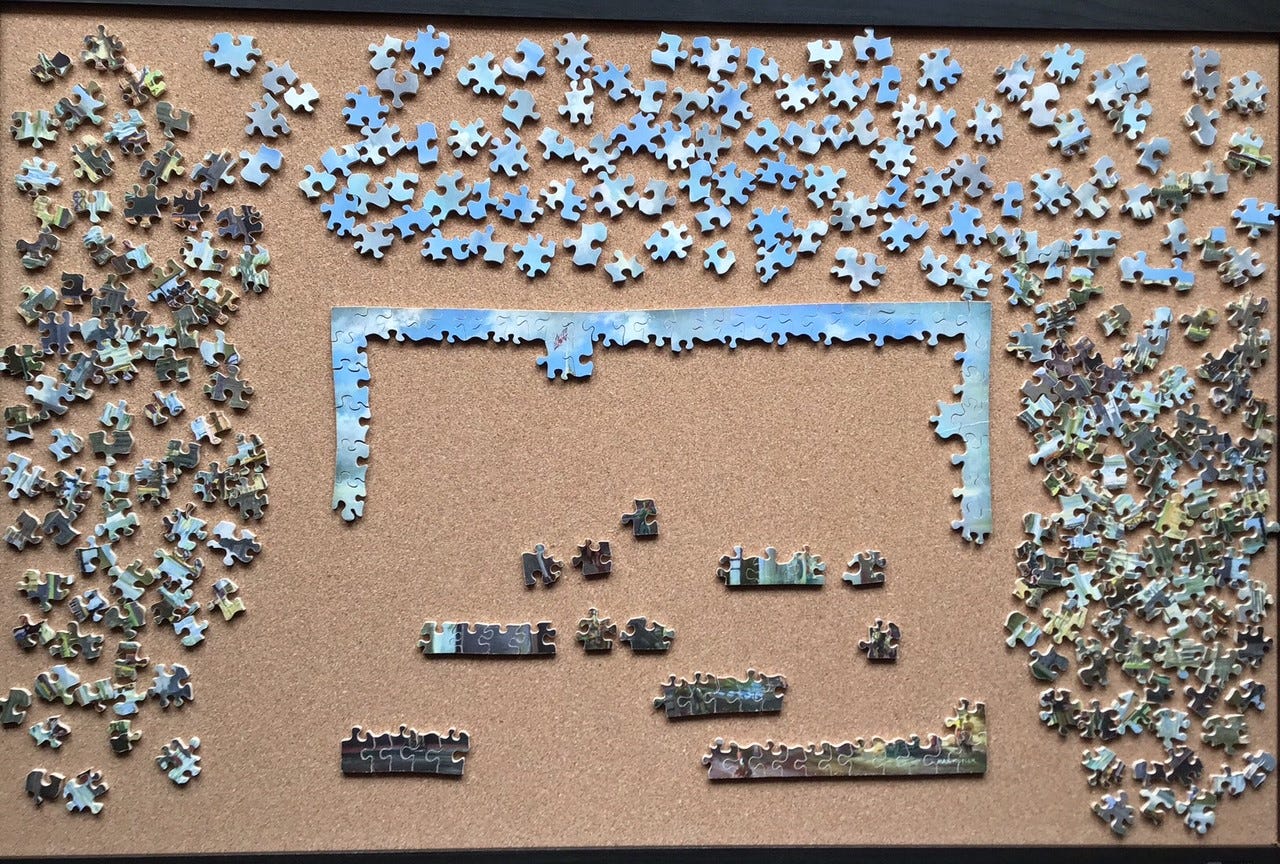

As you can see from the above photo, I began by using the classic edge-first assembly strategy. [Update: I almost never do puzzles edge first anymore. I prefer to build the image’s focus of attention first. In this case, not knowing what the final image would be, I would probably start with the brightly coloured pieces that become the bus, orange building façade and the green roof, and and the people.]

The wear and tear of the box is not indicative of the condition of the puzzle: The pieces are in great shape! I wouldn’t be surprised if it has only been assembled by the original owner and then again by the fellow who I bought it from second hand. I expect it is going to continue to be a real treat to assemble.

In respect for the puzzle’s English roots I am drinking tea with milk and sugar while I put it together, and aim to assemble it no-peek (although its image won’t be a complete surprise – I did see a photo of the completed puzzle about a month ago when I bid for it.)

I know from Wikipedia that this puzzle was made by G.J. Hayter & Co before the company was sold to J.W Spear & Sons in 1970, so it must have been made before that time. Can anyone here provide any more information about when it was made based on the box design or labeling? [Update: In the ensuing discussion Rob Coy told me that the packaging looks very much like similar puzzles he has that were made in the early 1960s.]

Progress report – March 19

Here’s a progress report on my first hand-cut puzzle. I am getting a lot of enjoyment from putting this 50+ year old puzzle together without having a reference picture. The 5 mm thick 3 ply pieces are comparable to the 5 or 6 millimetre (1/4”) 5 ply wood that seems to be the standard now for North American jigsaw puzzles, but thicker than the 3 mm thickness that seems to be common for new European- and Asian-made puzzles. The look and feel seems like a premium puzzle.

The stylishness of the then-contemporary passers-by is a treat. This image appears to have been painted when I was a teenager. From my meagre knowledge/memory of women’s fashions I am guessing that the artist, Venus, painted the watercolour in the early 1960s. I presume that it portrayed a contemporary view of London when this puzzle was made. But I doubt that there will be many more such clues coming since this is probably primarily an architecture picture.

The big difference from modern wooden puzzles seems to be in the paper and printing, and it really brings to my attention how much our technology has improved in the past half-century. The uncoated paper is soft and subject to edge fraying. The upper right hand corner of the puzzle has occasional little brown specks, as if the original assembler sneezed and sprayed some of his or her Tetley on it. I carefully tried to clean one tiny spot off but that just made it worse, so now I think of the tea spots as patina.

I am obviously spoiled by the substantial improvements in printing technology that have been made in the past 50 or 60 years. The overall impression from this print is that the image seems dry and indistinct when one studies the details, as puzzlers must constantly do. This really makes me appreciate the vibrant colours now available to modern printers and puzzle-makers.

Does anyone know if these paper and printing drawbacks are inherent in old puzzles, or limited to the inexpensive puzzles such as the Victory brand? [Update: I have since learned that both the printing and the cutting of this puzzle is quite good as vintage puzzles go, and that too may be part of the reason why this puzzle was more expensive than is usual for vintage puzzles of this size.] Also, I would appreciate if anyone can give me a more accurate estimate of when this puzzle was made based on the design or labeling on the box.

Please don’t take these critiques as griping. I am having a lot of fun with this 400 piece puzzle, and for $70(USD) including shipping it was a good value.

Progress report – March 20

I promise not to post progress reports for all on my puzzles, but the artwork in this vintage one really has me fascinated, and it is my first hand-cut puzzle.

More skinny-legged ladies have appeared, portrayed as in fashion designers’ sketches. Assuming that this weekly-released puzzle was made soon after the eponymous Venus painted it, that would seem to confirm it was made in the early to mid-1960s. That is also consistent with the labels on the box. (Thank you Rachel, Jim and Roy!)

[Update: Shortly after completing this puzzle I remembered that my friend Beth Skala would be able to date this image based on the fashions. She often needs to date old photographs for her hobby of genealogical research. Also, she was raised in California and her mother was very up-to-date about fashion. I sent her an email with the above close-ups and my speculation that the image is from the early 1960s. Here is her reply:

I think you have this properly pegged at early 1960s. Hats died out toward the later 1960s, but Jackie Kennedy made the pillbox hat popular in the earlier part of the decade. See this link.]

I’m really coming to appreciate Venus’ painting, with its contrast between the crisp clarity of the foreground street scene and the soft washes used for the architecture. It really gives the painting depth. Puzzling sure does draw one’s attention to painterly details. I tried to track down Venus’ identity, but to no avail. But she was the artist for a number of other Victory puzzles of London street scenes around that time. I hope that I can find more of them in online auctions.

I am getting to the hard part now - all in soft edges and greyscale. I should be finished later today but will be distracted by TV broadcasts of the beginning of the F1 racing season and the Canadian team has two games today at the World Curling Championship. There is no actual legal requirement that Canadians must watch whenever our curling team plays in the World’s, but that is probably because there doesn’t need to be one. I understand that the Americans also have a big sporting event going on now too (that they call March Madness.)

Final St Paul’s post – March 20

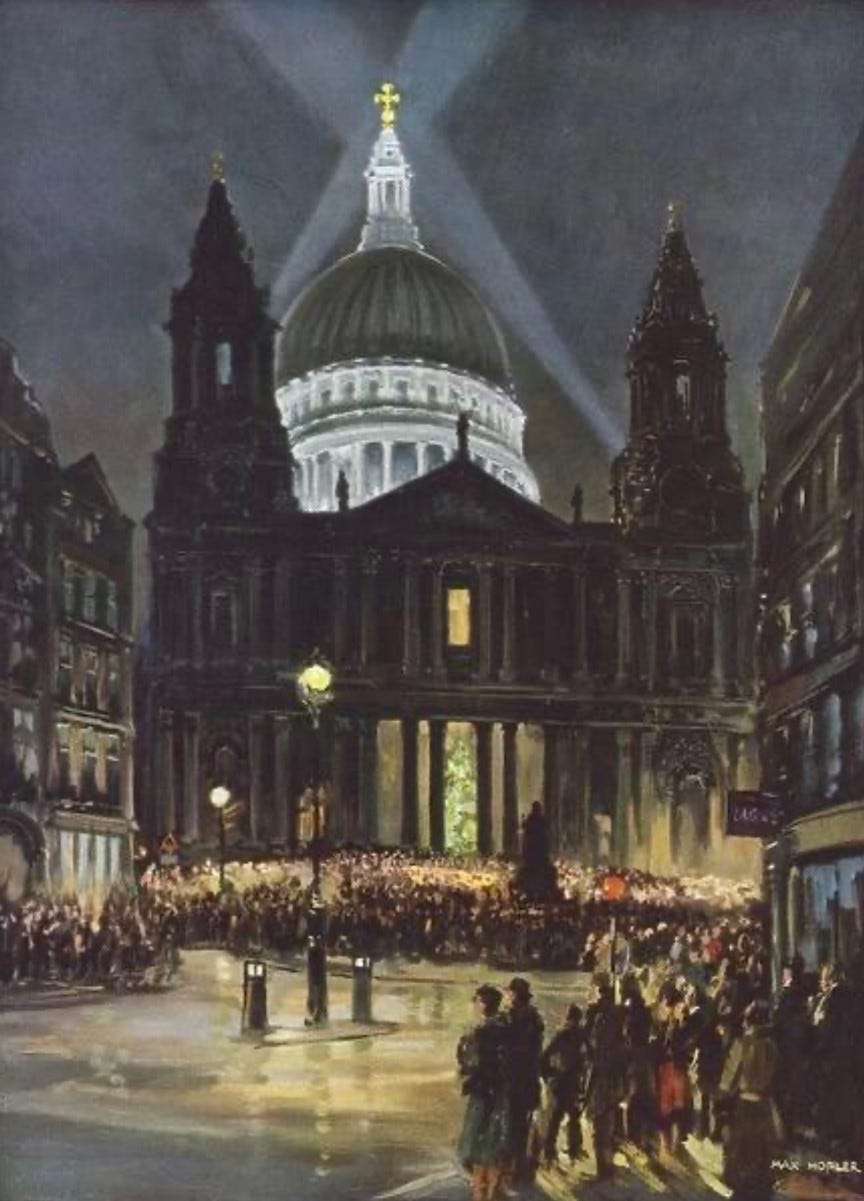

It’s finished! As I expected, this 400 piece vintage Victory puzzle wasn’t too difficult so I was able to complete it without referencing the photo in my eBay account records. After I was done I looked online for photos of St. Paul’s. I wanted to see the architectural details of Christopher Wren’s masterpiece, since the artist gave more attention to the street scene in front of it than to the building.

As I was working on this puzzle I became more and more appreciative of this commercial artist’s work. The buildings in this watercolour are mostly done as a soft wash, compared to the dry-brush foreground street scene images. (This distinction is very evident when studying the details as one does when assembling a jigsaw puzzle.) I thought that was interesting considering that this picture falls into the general niche of being an architectural puzzle, but for me it was the foreground street scene that was the highlight, set against an architectural backdrop. The result is rather like a photograph in which the focus is set on the foreground rather than on the cathedral.

I’ll definitely keep my eyes open for more Victory puzzles with artwork by “Venus” as well as other vintage wooden puzzles. They do offer a reasonable frugal alternative to intersperse with premium quality laser-cuts. (While working on this puzzle I have been on a spending binge getting a bunch of both kinds.) New hand-cuts are indeed expensive, but quite reasonably so given the amount of labour involved and the feeling of luxury that they give. I have come to appreciate that puzzle design is a work of art in itself, quite independent from the image on the puzzle, and that art seems to be currently enjoying a renaissance.

The nostalgia factor in the image on this puzzle was fun (painted when I was a teenager) but the picture has also brought to my attention to the fact that the technology of printing has improved by leaps and bounds since this was made. It is a great time to be getting into wooden puzzles.

So now, on to getting my nostalgia from the smell of a bonfire: A newly laser-cut puzzle made by Stumpcraft is calling me: Bursting Blooms.

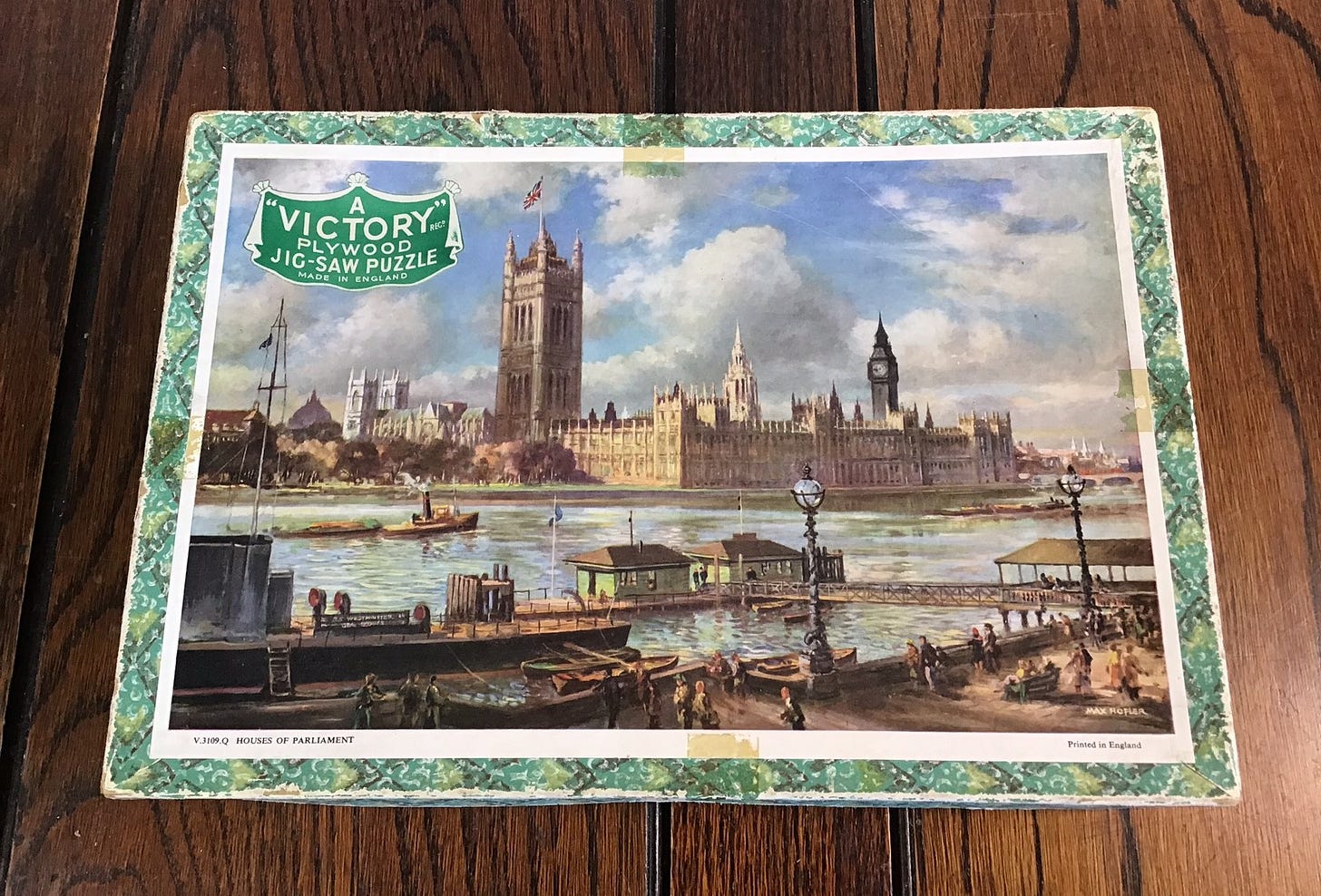

Houses of Parliament

factory hand-cut; G. J. Hayter & Co. Ltd.

Victory Popular Series (grid cut; no whimsies); made ca. 1960

17.5” x 11.4” about 350 pieces 4 mm plywood

Hayter made puzzles in various grades of quality and price, all under the brand name “Victory”. This puzzle is from one of the company’s least-expensive lines, called the Popular Series, which they launched in about 1931 when the company transformed from being a sideline family business into a factory style of manufacturing. Although the printing was up to the standard of their pricier puzzles, the 4mm thick plywood used in this puzzle is thinner than the 5 and 6mm (1/4”) thick wood used in their higher-quality puzzles that which were sold in elegant gold boxes with no picture on the cover.

The cutting of the Popular Series was also simpler, done purely in the interlocking grid style with no figural pieces.

The pieces of this puzzle are the same shape as stereotypical cardboard jigsaw puzzle pieces because such a grid was needed to make cutting dies more sturdy. To press-cut cardboard the crossed interlocking shaped blades need to be soldered or brazed together for strength. It is a lot more complicated make such cutting dies when the blades do not cross each other at every junction; hence, the four-sided shape of the pieces. (Although computer design is beginning to enabling that to be done so higher quality cardboard puzzles are beginning to look more interesting.)

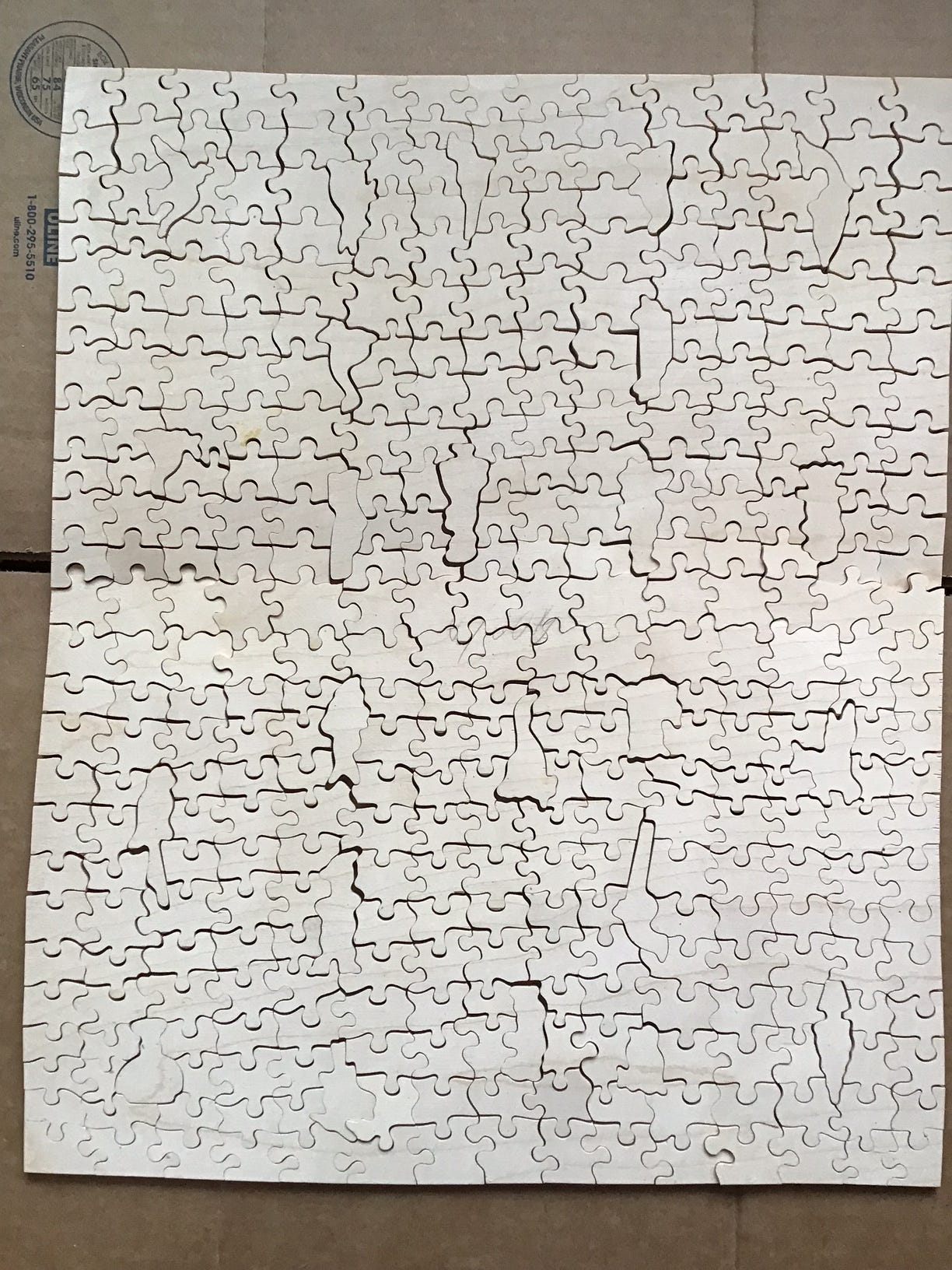

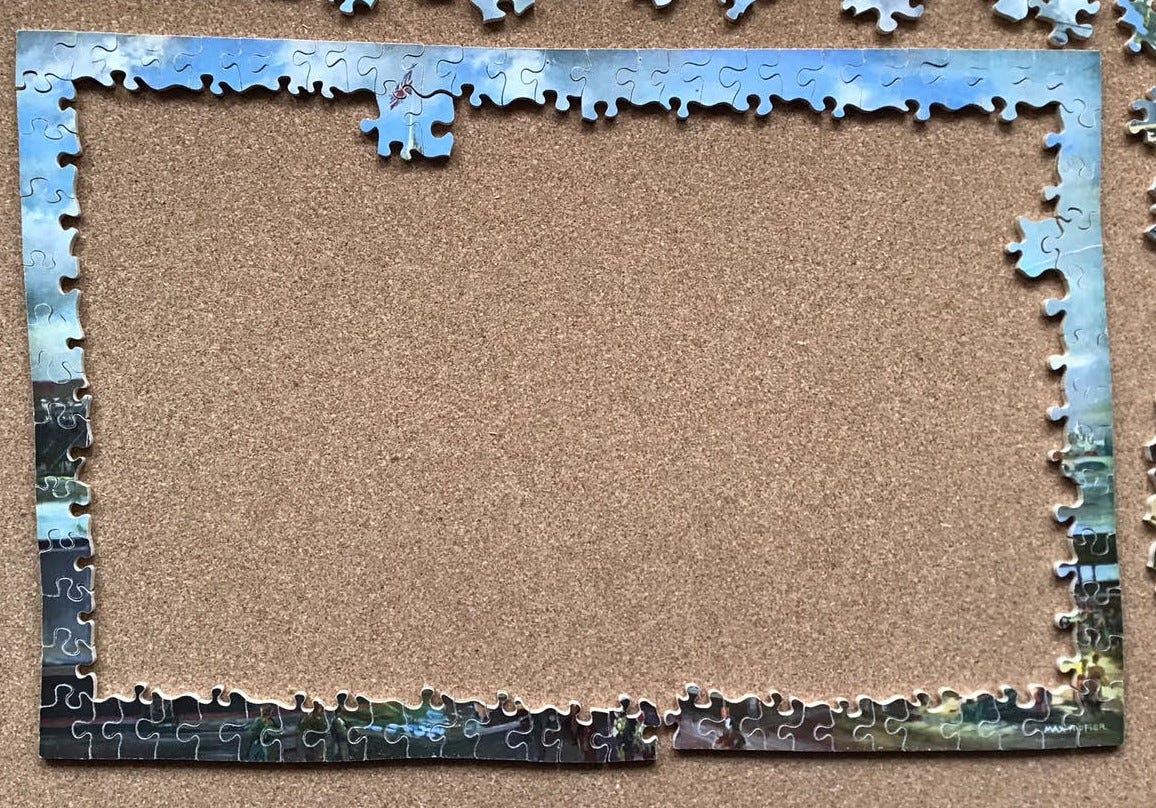

Here is how I assembled this puzzle. As with St. Pauls (London Scene) I began with the edges:

I don’t know if this is a general characteristic of the Popular Series, but like the Optimago brand puzzle that was the subject of my very first essay in this series, the sides of the pieces of this puzzle are very coarse. [Update: I now know that this means that the puzzle was cut with saw blades that had large aggressive teeth. Such saws enable faster cutting on the scroll saw. That meant that the cutters, who were paid by piece work, could make more puzzles during a shift, but the overall effect is not as pleasing as using finer-tooth sawblades.]

Other than that, and the fact that there is one place where there is a slight wrinkle in gluing the paper to the plywood, I have no complaints about the fabrication of this particular puzzle. I did have a more enjoyable experience from assembly of the three G.J. Hayter gold-boxed puzzles that I have assembled so far. But I can see that the Popular Series was reasonable way for working-class people to be able to afford a genuine wood puzzle back when this was made in the 1960s. Because such puzzles are less in demand from collectors, the lower auction prices they command online still make them a good “frugal alternative” for assemblers now.

[Update: I didn’t know when this puzzle was made but when I posted my review of this it on Facebook in 2022 the above photo gave readers more knowledgeable than myself some important clues. Peter Biddlecombe noticed that the price says “including purchase tax.” That tax was introduced as a war measure in 1940 and the name was changed to VAT in 1973. Rob Coy noticed that the box style and price are identical to another Popular Series puzzle of the same size. Puzzle expert David Shearer dated that one as having been made circa 1960.]

[Update: Usually one only turns puzzles over to look at the back side to see if there are any surprises with the figural pieces (which sometimes can be previously-unrecognized multi-piece figurals or whimsies that relate to each other in interesting ways. But in this case it was only by looking at the back while doing this repost that I recognized that the cutter had skipped some of the connectors on the horizontal cut lines. This trick both saves time for the cutter and also adds more interest for the assembly than a pure grid cutting strategy.]

All in all, this was a fun puzzle despite the lack of entertainment from figural pieces. I’ll happily do this one again someday when I want a simple and fun puzzle. But actually, as I often find, I got even more enjoyment from doing my post-assembly research into the artist who painted the image.

The painting and the artist

I didn’t buy this puzzle because I liked the picture. I bought it because it sold at auction for such a good price for a vintage 350 piece wood puzzle, and I had already won an auction that weekend from the same seller in England who could combine it in the same shipment. As it turns out though, while assembling it I developed considerable fondness for this image and my post-puzzle research has proven to be very interesting.

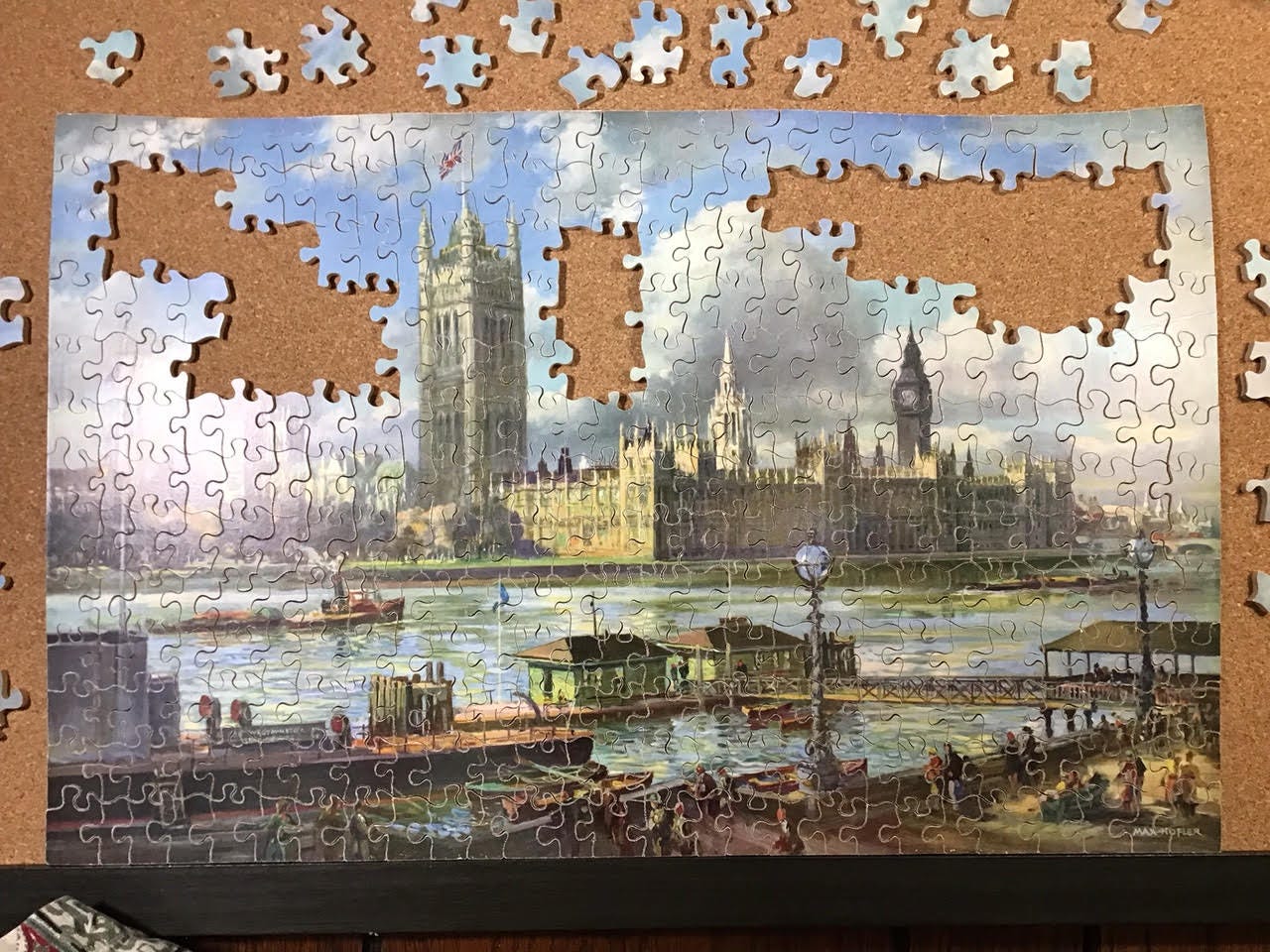

I’ve never been to London, but I have seen my share of pictures of the Houses of Parliament. When I first saw this puzzle I thought that it didn’t resemble my memory of what the building looks like. It turns out that is because most of the tourist pictures of the famous landmark feature its façade and the famous Big Ben Clock Tower (now re-named the Elizabeth Tower.) This painting is of the back-side of the building formally known as the Palace of Westminster. This foreshortened view from across the Thames highlights that tower’s just-as-old and just-as-tall (but far-less-famous) sibling called the Victoria Tower. It also shows off the gleaming white gothic octagonal Central Tower above the core of the building, and includes the neighbouring gleaming white towers of Westminster Abbey and the dark dome of the Methodist Central Hall.

From the Google map of London I was able to determine that the vantage point for this painting was from the Albert Embankment on the south side of the river, with the Lambeth Pier (built in 1860) in the foreground. That pier is still in use today, mainly as an embarkation point for tourist boat excursions on the river.

The painting is by Max Hofler (1892-1963.) He was born in Middlesex, England to Australian immigrants who were not financially well-off. As a child Max was drawn to painting and had a talent for it. At the age of 14 he was granted special permission (and possibly a partial scholarship) to attend Heatherly’s School of Fine Art, and later the St. Martin’s School of Art. I read one account that after secondary school his parents refused to continue to pay for his education unless he studied something useful and more financially promising. Young Max chose architecture and that became his “day job” for half his adult life.

But he still loved painting (especially, as this one, oil-on-board paintings of maritime and architectural subjects.) After his architectural training he articled with a London architecture firm and became a Fellow of the Royal Academy of British Architects.

Somewhere along the way he took five years of evening classes at the Royal Academy Schools. In the late 1930s a few of his paintings were accepted to be shown at the Academy. Sometime during his career Max stopped working as an architect and became a full-time painter. But that architectural training was not wasted: Although he also painted rural landscapes, depiction of architecture became a strength of Max’s paintings. Interestingly, my online research found many of his paintings, but absolutely nothing about any of the buildings that he designed or participated in designing as an architect.

Hofler was one of the founding members of what came to be called The Wapping Group of Artists. It began in 1939 when some members of the Artists Society and the Langham Sketching Club began to meet together after club meetings at the Prospect of Whitby Pub in Wapping (on the east side of London.) They decided to organize weekly (rain or shine) en plein air sketching/painting outings along the London shores of the Thames River from May through September. Their outings were soon discontinued due to the War but they re-formed in 1946. The club continues to this day (although the range of their outings now has expanded down-river to the estuary and up-river to include a few of the Thames’ tributaries.) Here is their website.

I do not know if the painting used as an image for this puzzle resulted from one of those painting excursions but its riverfront location certainly fits within their scope. Besides famous landmarks such as this (a subject matter that had better prospects for licensing or sale) many of their paintings are of the gritty, working harbour aspects of this part of London. And even if it was a result of such an excursion I don’t know whether this is an en plein air painting or was a studio painting made from field sketches made with the group. The members used both formats. Either way, collectively the Wapping Group’s work over such a long span has left a valuable documentary record of evolution of London’s Thames waterfront.

I cannot find any information about this particular painting and therefore can also only conjecture regarding when it was made. We know that it was painted sometime before 1954 because the image had been published as in an unknown magazine and David Shearer’s The Jigasaurus website shows a puzzle with the image that was made by Dolly McDougall in that year. Judging by the many other Max Hofler paintings I found online my guess is that this may have been one of his earlier works with the Wapping Group.

I intuitively thought that both this picture and the puzzle could have been made shortly before WWII. The steam tugboat would be consistent with the painting being from that date, and (possibly) so would the hemlines of the ladies in the foreground.

Judging by the way folks on the embankment are dressed, it looks like a cool day and they are prepared for the cloudbursts the ominous sky suggests might be coming. In the symbolic language of art, as a Royal Academy-trained artist would know, that is a foreshadowing of danger. Although WWII did not begin until September of the Wapping Group’s inaugural year concerns about an upcoming war with Germany were rising in England throughout 1939 as it was becoming apparent that Neville Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement was not working.

On the other hand, if this painting does include such a foreshadowing of war one might expect at least one of the foreground figures to be in uniform. And the threat in those clouds is rather subtle. Max Hofler certainly knew how to portray a more threatening mood in his clouds if that was his intention:

Foreshadowing or not, the Wapping Group’s weekly field trips began in that same summer and this vantage point, which is within easy walking distance of Wapping, seems like a perfect location for a painting/sketching a group excursion by a new group of artistic comrades.

Doing all this research led me to appreciate Max Hofler’s artistry, especially his attention to architectural details. He continued to paint right up to the year that he died. His paintings tend usually to be oil-on-board and they are often quite small, suggesting to me that he did indeed paint en plein air even when he was not on a group excursion.

My impression is that his painting style was quite conservative for his time, and his choice of subject matter for most of his non-waterfront paintings seem to have an eye towards commercial viability. His waterfront paintings, on the other hand, include a high proportion of gritty working locations that do not seem to have as much potential for a commercial painting. That suggests that he enjoyed painting with the Wapping Group wherever they chose to go.

There are many more to see online but here are some of his other paintings:

Thanks, Bill for today's posting. I particularly enjoyed the paragraphs about your strategies to indulge in you hobby somewhat frugally, and the tradeoffs involved when it came to acquiring less expensive used puzzles that were were still enjoyable but may have lacked some of the benefits of modern cutting and colouration. I appreciated the wealth of photos included, too. My favourites among those were "Gathering Storm," "Dock Scene," "Christmas Carols at St. Paul's," and "Hyde Park Corner, London." I even have a soft spot in my heart for the Victory box cover from the puzzle that you said you had not primarily bought because of liking the picture. By the way, based on y own limited experience with wooden jigsaw puzzle pieces, I share your opinion that thicker pieces are most enjoyable.

Regards,

Greg