1. The “Lightning Express” Trains. "Leaving the Junction."

A puzzle review/essay (about 2500 words; 12 pictures)

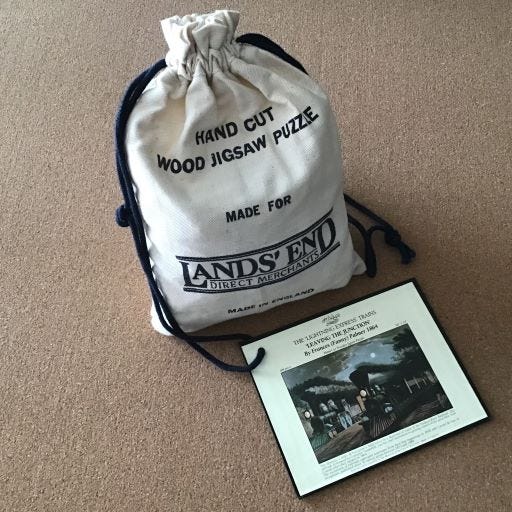

factory hand-cut Optimago Ltd, for Lands’ End Direct Merchants

artist – Frances “Fanny” Flora Bond Palmer; 1863

308 pieces 13” x 16” (32.5 x 41 cm) 5 mm plywood

This is a review of a previously-unassembled hand-cut puzzle that was made by the prolific London-based English company Optimago Ltd who were in business from 1979-2005. While assembling this puzzle I have come to think of that time period as having been the final dying days of jigsaw puzzling’s once-booming Golden Age. That era began in the 1920s and ‘30s, when cutters in factories made literally millions of inexpensive hand-cut jigsaw puzzles for the masses every week.

The artwork on this puzzle

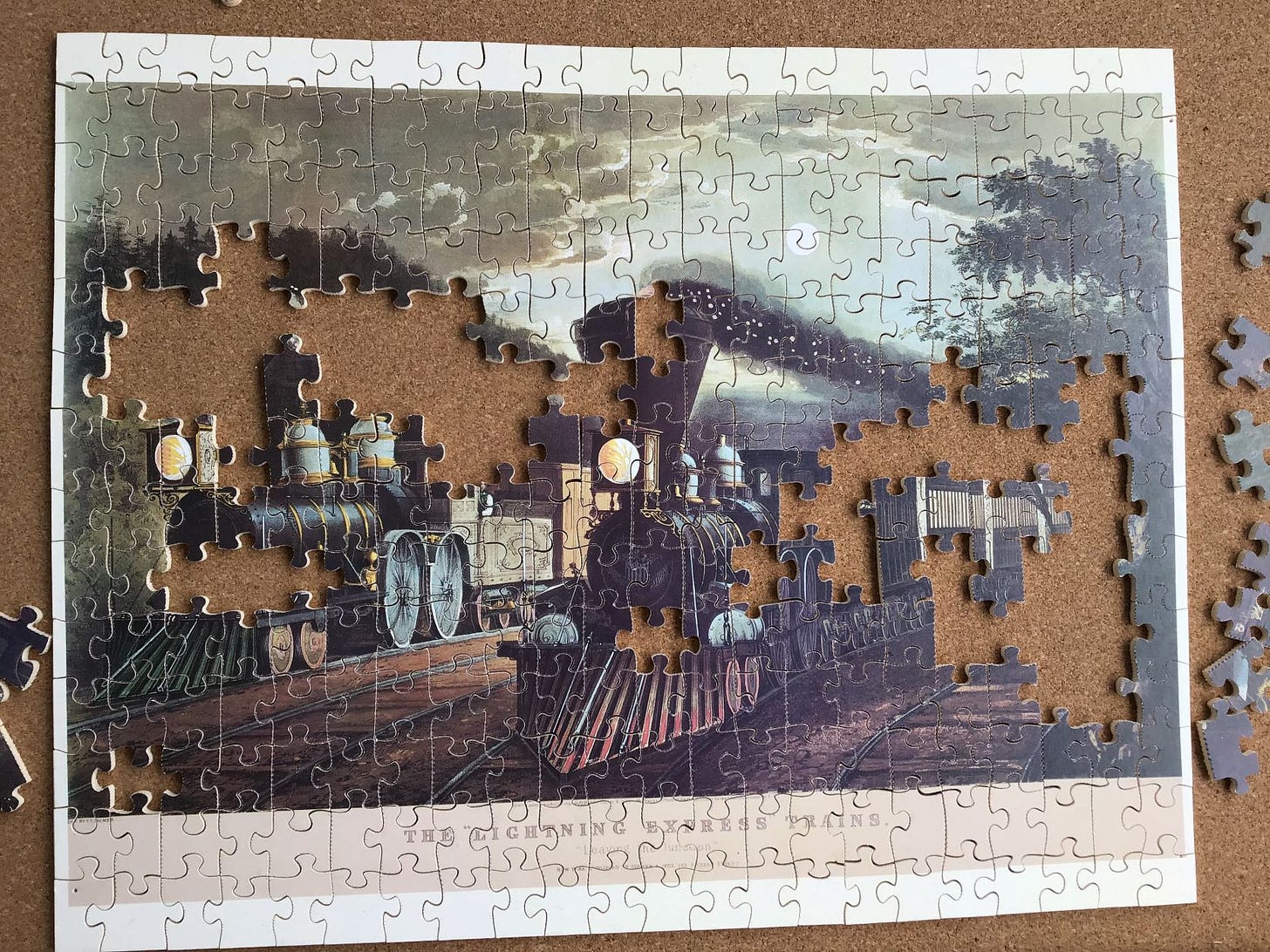

I’ll begin this puzzle-review/essay by discussing the picture and its back-story, this puzzle’s most positive features. The image on the puzzle is a good-quality modern reproduction of a famous Currier & Ives lithograph made in 1863 or ’64 (there is conflicting evidence about the exact date.)

Here is how a Currier & Ives advertisement described this picture:

Here we have an exciting episode on the rails. Two night express trains, leaving the junction, run side by side for a short distance before their roads diverge - the engineers are indulging in a trial of speed, the one locomotive coal, and the other wood. The huge monsters, with their reflectors like eyes of fire and belching forth flames and smoke, seem to be rushing on with lightning velocity and the first impulse of the beholder is to clear the track to avoid being run over. Meanwhile, the moon calmly looks down, bathing the landscape in a flood of mellow light.

As I see it (after being immersed in its details as a puzzle-assembler) this moon-lit image is a romantic view of then-contemporary early steam trains - that era’s most advanced means of transportation. And it is a lithograph. At that time, lithography was taking over from etching as the state-of-the-art way to print pictures in the finest detail. Thus, together, the image and medium constitute a Glorification of Progress, which was a very popular artistic genre during the 19th century.

The excitement and progress represented by railroads immediately captivated Americans when this new technology was were first introduced to that country in 1830. Because of their popularity, Currier & Ives published about 30 railroad lithographs between 1853 and 1884. This one is considered to be their most dramatic rendition. The depicted trains are believed to have been operated by Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Hudson River Railroad. For more perspective on the artistic merits and context of this image I recommend this interpretation of the lithograph from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Lithography

I did not know how lithography differed from other types of printing so I had to research that topic. Lithography had been invented in Bavaria in 1796 and was still in a state of development when this one was made. It is a method of printing in which a very fine-line drawing can be made on a stone slab and becomes affixed to it through a chemical process that is based on the fact that grease repels waters. The image can then be reproduced in ink onto paper from the stone with great accuracy, through the same chemical process.

If you want to learn more about stone lithography, here is a brief illustrated essay about the process and its history, and here is a five minute video that explains and shows it being done. And, of course, its Wikipedia article offers a much deeper dive into the topic and leads to other sources of information.

At the time that this lithograph was made colour lithography was yet to be invented, so for a colour print like this one the black-and-white lithograph print was hand coloured by means of watercolour painting. One of Currier & Ives’ innovations was applying assembly-line methods to this hand colouring, enabling good quality prints to be much more affordable for everyday people.

The colourists were mostly immigrant women who had artistic training or experience. Each colorist applied a single color to the print, and then passed it along to the next colorist on the assembly line. The best artists were at the end, adding the most difficult elements and touching up where needed to try to replicate the master colour image that had been painted by the artist.

The Currier & Ives Company was not only one of the leaders in developing and improving lithographic processes, they were also the best American producer of high quality, relatively inexpensive lithographs at the time. While the ink image was always the same (from the same stone block) different degrees of care and attention to detail at the water colouring stage meant that they could be slightly, or even radically different from each other. (Compare, for example, the flames and sparks emerging from the smokestack in the above museum print to the assembled puzzle image later in this review/essay.)

That, as well as condition, is why there can be a wide price-range for original Currier & Ives lithographs. Because they were abundant, even if they are in good condition, many original C&E lithographs often sell for only about $100 today. But because this particular litho is famous and iconic, and was a larger-size more-expensive print when it was new (and therefore is more rare than most), originals of it are in high demand by collectors and museums.

The original lithograph stone still exists, and still works. New lithographs were made from it in the 1940s and 1970s, long after Currier and Ives ceased to exist, and even they command prices in the several hundred dollar range. In 2004, a slightly damaged but very high-grade version of one of Currier & Ives’ original lithographs of this picture sold at auction for $25,850 USD.

The artist

The artist who drew and refined the original sketch for The “Lightning Express” Trains. “Leaving the Junction.”, drew the picture in detail onto the lithograph stone, and painted the master coloured image that the assembly-line colourists tried to copy, was Frances “Fanny” Flora Bond Palmer (1812-1876.) She was the first woman in the United States to work as a professional artist, and to make a living for her family through her art.

Fanny was born in Leicester England. As the daughter of an attorney she received an excellent artistic education at a private school for young ladies run by a noted crewel embroiderer, before moving to New York as an adult. In both Leicester and New York she and her husband Edmund established lithograph companies based on her artistic abilities.

Both of her lithograph companies received acclaim from art critics, and in New York both her artistic abilities and lithographic skills caught the attention of Nathanial Currier, who contracted with her to produce art for his own company. When her company faltered (because Edmund was a drunken ne’er-do-well) Currier bought her out and hired her. She became and remained the only female member of his artist and lithographer staff (as distinct from the assembly line colourists who were nearly all female.)

The story of Fanny Palmer is a fascinating one, but I need to get back to this being a puzzle review. I highly recommend that you read more about her from this blog article. How important of an artist was she? Well she certainly doesn’t get much attention from art historians because she is seen as having been “only an illustrator” not an artist. The general public didn’t know her name, and even if they did look at the fine print below the image they didn’t know her gender – she was simply identified as F. F. Palmer. But it has been estimated that in the 19th century more American homes had pictures by her hanging on their wall than by any other artist in the world.

To show the range of Fanny Palmer’s work here are two of her other lithographs:

Puzzle design and assembly

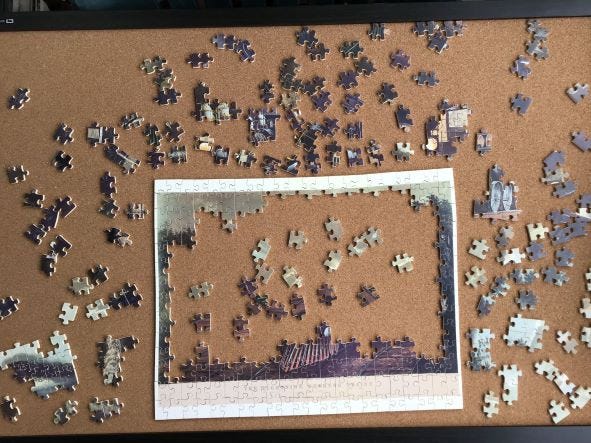

I wish that Optimago’s wood puzzle lived up to the standards that this image deserves. Unfortunately it doesn’t for a variety of reasons. The first is the simplicity of the cutting design.

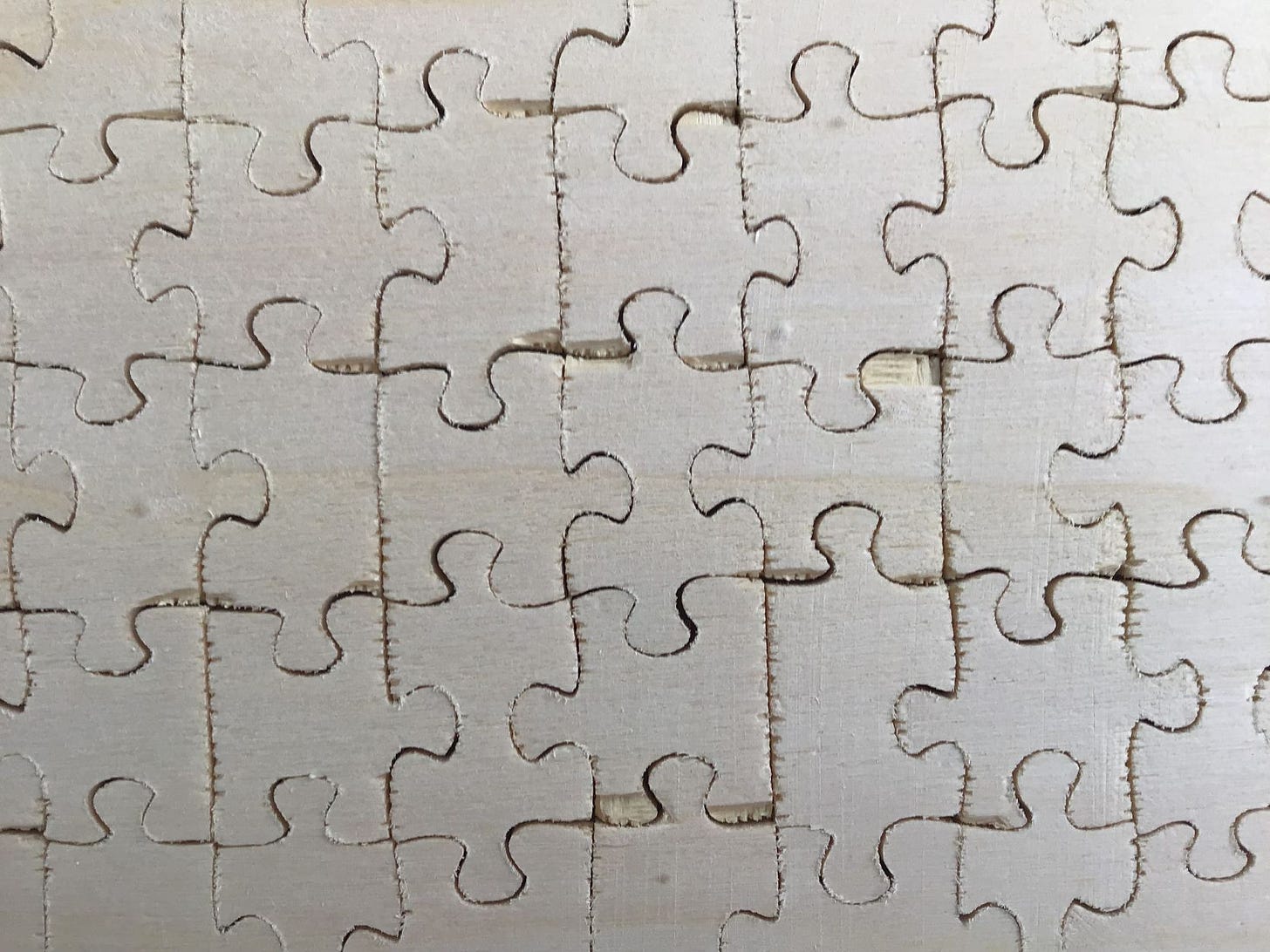

As you can see, this is about as simple as cutting can get. Vintage puzzle collector and restorer Bob Armstrong has developed a classification system to describe cutting styles and calls this one strip (grid) cutting with interlocking round knob connectors. This cutting is similar to a rather poor die-cut cardboard jigsaw puzzle. As Bob notes about another wood puzzle with such a cutting design: “One wonders why the maker took the time to hand-cut the puzzle in the first place. Probably it’s because that’s the easiest and least imaginative way to cut a puzzle and reflects the maker’s objective to produce one as quickly as possible.”

I have since learned from the Optimago gallery on David Shearer’s very informative The Jigasaurus website that this simplicity was a house characteristic of most Optimago puzzles (except their premium “Fancy cut” and “Enigma” lines.)

This puzzle’s cutting does include one trick usually intended to make a puzzle more challenging (as well as quicker to cut.) Note that the vertical cutting between 1/3 of the interior pieces is a straight line rather than including an interlocking knob. This creates an abundance of false edge pieces. But any extra challenge this could present is totally undermined by the image’s obvious beige margins on the actual outside edges.

As you can guess, this puzzle proved easy to assemble. The only real challenge was that, because there are areas with little or no colour differentiation, the uniformly sized and shaped knobs caused me to make incorrect fits (especially along the edges) that needed to be tracked down. While false fitting would normally be irritating, in this case it was a welcome bit of assembly challenge.

Quality control problems

Another issue detracted from the aesthetic experience of seeing the image develop as the puzzle was assembled, and from the appearance of the finally assembled puzzle. The sawblade that was used, especially for the vertical cuts, seems to either have had particularly aggressive teeth or some teeth sticking out to the side. They gouge into the pieces creating little notches, accentuating the visibility of the cutting lines.

Another quality issue is that the wood of this puzzle seems to be soft, more so than in any other puzzle I have assembled so far, vintage or new. This means that it is prone to splintering and chipping on the back of the puzzle.

The front of the puzzle pieces were not affected by this, and the splintering was only noticeable while I was doing my initial sorting and after the puzzle was completed (when I turned it over to see and photograph the back side.) However, the soft wood, together with their 5 mm thickness, meant that the pieces did not have as much heft to them as those of a birch ¼” (6 mm) plywood puzzle. They also did not make as satisfactory of a clicking sound when they were put into place.

I inquired to other participants in the Facebook Wood Puzzle Club as to whether they also had experienced these sawblade and splintering/chipping issues with Optimago puzzles. The replies were mixed. A few people reported that they had not seen this in the Optimagos that they had assembled, but others said that such problems were common with that brand.

These quality issues caused me to have occasional dark thoughts during assembly. I found myself reminded that, as with the many puzzles that were made in the “Golden Age” of wooden puzzles, this one was cut by a factory worker, not by a craftsperson. Did that person get satisfaction from producing puzzles at this level of shoddy quality control standards? How were the workers at various puzzle factories treated by their employers? What were their working conditions like? Were the puzzle factories as bad as the garment industry’s well-documented sweatshops? Or were workers treated compassionately and happy to have a job?

[Note: I could not find answers to these questions online, so was motivated by these questions to order a couple of out-of-print jigsaw puzzle history books; one by Anne D. Williams, Jigsaw Puzzles, an Illustrated history and Price Guide, 1990 (primarily about the American scene), and Tom Tyler’s British Jigsaw Puzzles of the 20th Century, published in 2006. Perhaps they will cover this aspect of jigsaw puzzle making, or include leads to where I can find answers.]

Similarly, I wondered about the pressures that Optimago’s London-based owners and managers were under during a time when jigsaw puzzles in general were at a low ebb in popularity. They must have faced fierce competition from the makers of much-cheaper die-cut cardboard puzzles. And in the final decade of the company’s 25 years, competition loomed from that new upstart in the north of England, Wentworths Wooden Puzzles, who were using a new laser-cutting technology that gave them a big price advantage over hand-cutting. It must have been a challenge for the company to last as long as it did.

Overall impressions and final thoughts

I wouldn’t want to end this puzzle review/essay on those dark notes, and fortunately I don’t need to. Despite what I have just said, overall I did enjoy assembling this puzzle. (It helped that I had only spent $30 US buying it.) I learned that even an unchallenging puzzle, with no whimsies or cutting tricks, and with mostly drab dark colours, can be a fun build.

The image of this puzzle includes interesting details on the early-vintage steam engines that were fun to discover. As the image developed it was like looking at another world – I saw these trains through the eyes of a mid-19th century woman who seemed marvelled by their beauty and technological elegance. The picture is about the machines themselves; the human drivers seem inconsequential. And passengers and cargo are not shown at all; they apparently are irrelevant. Although many of Fanny Porter’s illustrations relate to the nostalgic side of country life, I could tell from this one that she also shared in her era’s enthrallment in the concept of Progress.

And finally, as you can see by the length of this review/essay, this puzzle gave me a lot to think about.

Bill

PS Did you enjoy this long-form jigsaw puzzle review/essay? If you are not already a subscribe, that’s okay. Bookmark this page and come back anytime to see the newsletters that you’ve missed. See the About section of this website for more details.

Thanks for your research. I was especially pleased to see the race between a wood-fired locomotive and a coal-fired locomotive. I saw that picture long ago, though not used on a jigsaw puzzle.