30. Vintage puzzles made by Chad Valley

A brief history of the Chad Valley Company, two small puzzles they made, and digressions about puzzle libraries and packaging. (about 4100 words; 24 pictures)

The rise and fall of Chad Valley

The Chad Valley Company was the offshoot of a Birmingham-based family-run printing and stationery business that had been established in the early 19th century. In 1897 they spun off a subsidiary company that would specialize in making making high-end toys and erected a purpose-built headquarters and factory for the new company in the village of Harborne on the outskirts of Birmingham. The site had been chosen because it offered clean air while remaining close to the city, and because there was a branch-line railway that could be extended to both bring in raw materials and ship out the new company’s products.

Harborne is a very old village but in Victorian times it had evolved into a classy residential suburb on the outskirts of the expanding industrial city. The toy works would be the only factory there. It was located close to a small stream called the Chad Brook and the new building was christened the Chad Valley Works. Before long the toy company which was originally called Jones Brothers re-named itself the Chad Valley Company.

The Chad Valley Company designed and made many types of toys and games - from rocking horses, board games and toy trains to teddy bears and lead soldiers. They were mostly known for their high-end products: Brits soon began to refer to the company’s products as “toys for toffs.” What do I mean by “high-end”? Here is a description of their dolls from the Woolworth Museum:

What set the Chad Valley items apart was their exceptional detail. Dresses were in authentic materials, finished with lace and neatly pleated. Faces were designed with great care and hand-finished to a quality to rival Royal Doulton's porcelain 'Lovely Ladies'. Boy dolls proved very popular with the young ladies of the era, who loved their tweed sports jackets trimmed with felt collars, gun bags and of course neck ties. These were the types of clothes favoured by the country squires and aristocrats who bought the dolls. The popularity of the range rocketed when rumours circulated in 1937 that even the new Queen of England was a fan! source

Because the new company was focused on making children’s toys they missed out on the first boom in adult jigsaw puzzles that swept through the British upper classes and gentry in the first decade of the 20th century. But the Chad Valley company grew and prospered.

Surprisingly they even experienced a large growth spurt during the First World War because the government cut off the import toys and games to England for the duration. Previously, German companies had been the makers of the best toys and Chad Valley rushed in to fill that market vacuum. The Johnson brothers used their wartime profits to buy up the rival Wrekin Toy Company in Wellington, Shropshire, which greatly expanded their product lines, gave them the services of and experienced team of toy designers, marketers and workers, and gave them the capacity and tools to continue to ramp up production.

It was about 1920 when the company recognized that they were missing a big opportunity by not catering to the continuing popularity of jigsaw puzzles for adults. The jigsaw puzzle craze in the first decade of the century had abated but assembling jigsaws remained popular with adults not only as personal or family recreation but also as a form of social hospitality (much like inviting guests over for an evening of pinochle or bridge.)

So the company that made “toys for toffs” decided to begin making jigsaw puzzles for adults. But these puzzles wouldn’t be the like ultra-expensive children’s toys for which the company was famous. Instead, these toys for adults would be made from plywood just like their competitors, and their prices would be only a bit more expensive. Their Chad Valley puzzles would offer a form of recreation that was known to be popular among the gentry but to which middle-class people could treat themselves, their families and their friends to for only 2 shillings and a sixpence.

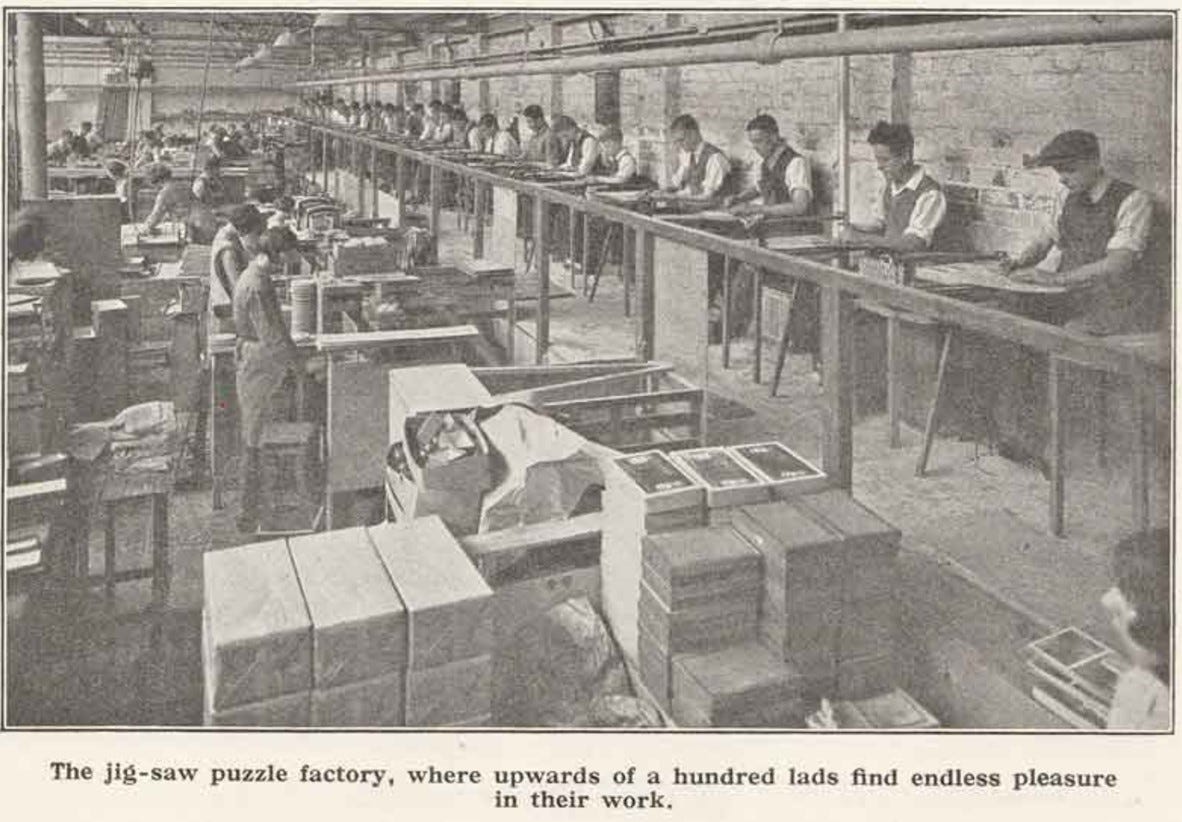

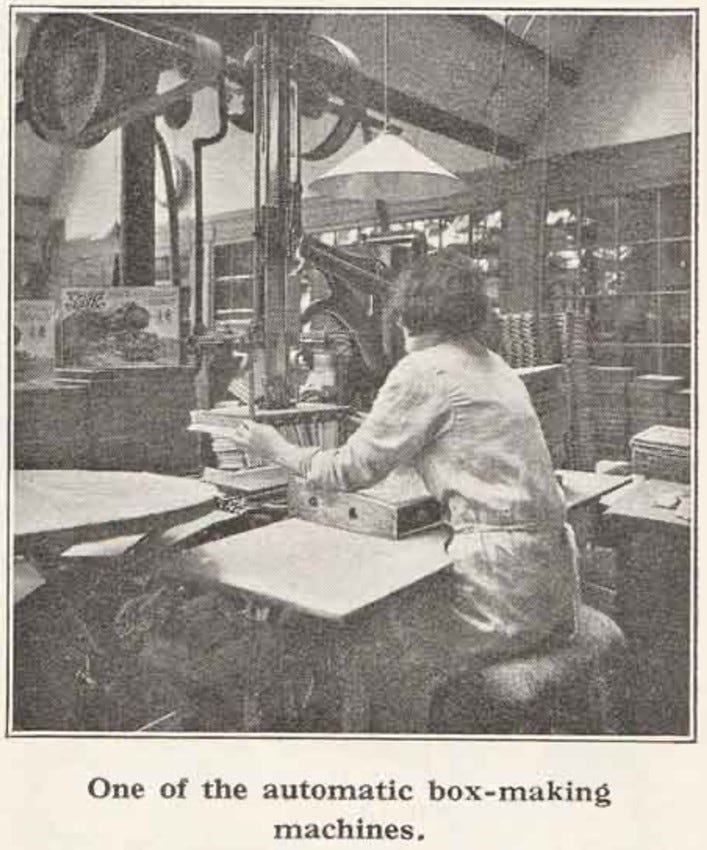

The company expanded the factory to set up its cutting shop. Making wooden jigsaw puzzles involves many steps. In an artisan workshop all of them are usually done by one person, perhaps with assistance from family members. In a factory all of the steps were done by employees who specialized in their various roles, from printing the image, cutting and preparing the plywood blank, gluing the picture to it, cutting the puzzle, inspecting them and putting the puzzles into boxes (which were also made in the factory), etc.

[Updated September 2024] The following photos of the Chad Valley shop floor and their captions are from a four page article in the September 1931 edition of the GWR Publicity Department’s Great Western Railway Magazine telling about a visit to the Chad Valley Works (images source):

I have suspicions abut these photos, especially the third one. All appear to be posed to feature GWR products on the shop floor. Why would the cutter in the third photo surrounded by boxes, unlike all of the other cutters in the previous picture. And is that really a working scroll saw? It has an incredibly deep throat and thin upper arm, and its huge work surface is only a flimsy thin sheet of plywood resting on a sawhorse. On the other hand, a jigsaw puzzle factory would need to have at least one very deep-throated saw to cut the blank of a very large puzzle (like the 26½” long puzzle The Torbay Express that I discuss in newsletter no. 40) into workable sized halves.

At the Chad Valley Company, like in all of the British puzzle factories at that time, the roles were gender specific. Only men did the printing and cutting, which were the higher-skill jobs, and mostly women did the other lower-paying factory assembly line work. Interestingly, in America those gender-roles were reversed and women were seen as the proper gender to be skillful cutters (since they were usually former garment workers who had experience using sewing machines swiftly and accurately.)

The company’s initial efforts at making jigsaw puzzles had quality control problems but by the latter 1920s their quality was excellent and Chad Valley was well-positioned to participate in jigsaw puzzles’ second boom that began in the early 1930s. During the Depression it was one of England’s Big Three puzzle-makers, along with G.J. Hayter’s Victory brand and J. Salmon’s Academy series.

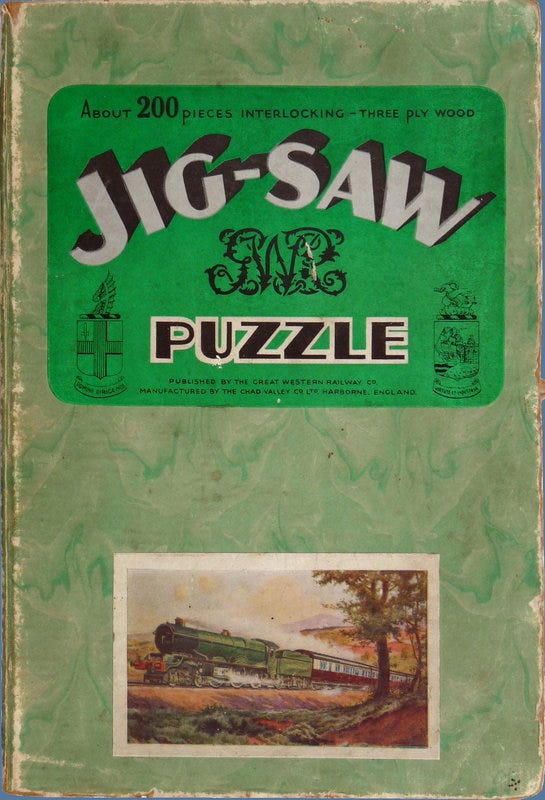

The company’s big break had come in 1924 when had been approached by the Great Western Railway (GWR) with a business proposition: The GWR asked Chad Valley to make puzzles for them featuring majestic images of the company’s iconic trains and ships. Chad Valley would sell them as GWR puzzles through their usual distribution channels and the GWR would then sell the puzzles to customers itself as souvenirs. Since they were to be a promotional product, GWR would subsidize their production so that they could be sold for the cost of production – 2s6d – a much lower price than other puzzles of their quality and size.

The first GWR puzzle made under this arrangement featured the Caerphilly Castle, the prototype of the railway company’s new Castle Class of steam locomotive. It had been designed to pull passenger express trains at the fastest allowable speeds. The magnificent new engine was to be the GNR’s feature attraction at the 1924 British Empire Exhibition, at Wembley. There it would be displayed for public nearly side-by-side with the London and North Eastern Railway’s famous Flying Scotsman and the GWR could tout (factually correctly in terms of tractive power) that it was the more powerful two. And only the GNR would have well-priced puzzles — made by the prestigious Chad Valley Company no less — available to sell to admirers as souvenirs of the event.

The puzzles were a huge success both for the GWR and for Chad Valley. 78,000 of them were sold. That led to many more orders for more puzzles from the GWR, and also to puzzles being commissioned under a similar arrangement by other firms like the Cunard White Star Line, the British India Steamship Company, and Dunlop Tires, who wanted to copy the same business model – puzzles made by Chad Valley but sold for the cost of production under their own names. Between 1924 and 1939 Chad Valley produced over a million such puzzles.

Besides contracting to make promotional puzzles, Chad Valley also frequently contracted to make puzzles for charitable fund-raising, and for branded or anonymous puzzles for department stores and other retail merchants. These were not Chad Valley brand puzzles themselves – simply puzzles that were made by Chad Valley – but in parallel to this Chad Valley also did make and sell puzzles under its own name and trademark. As far as I can tell Chad Valley made many more puzzles under these collaborations and contracts than they did under their own name and marque.

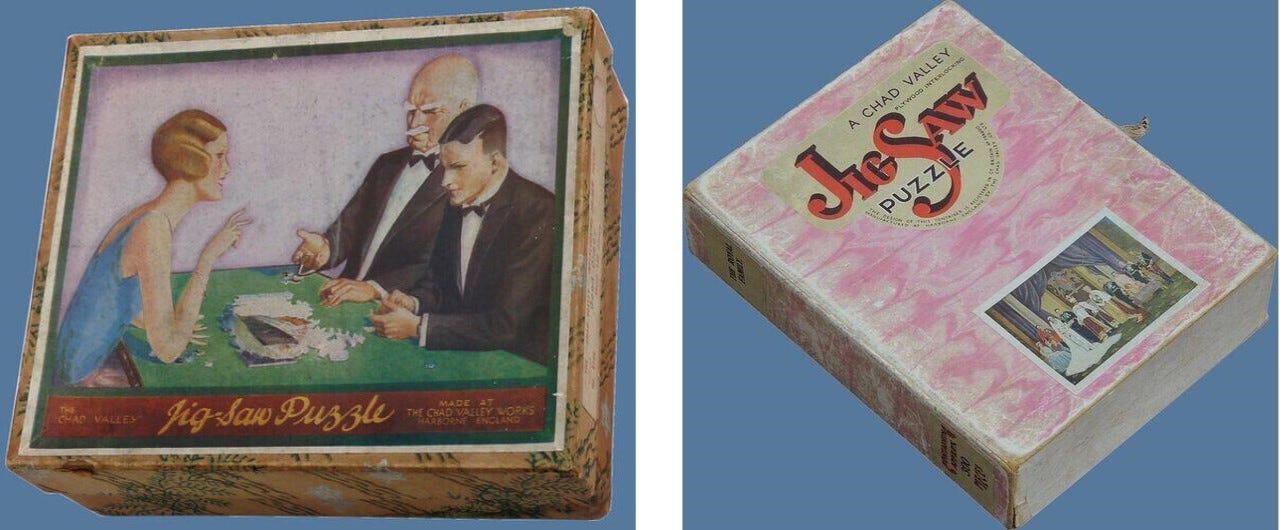

In the 1920s and ‘30s puzzle company’s generally had standardized styles of packaging to establish branding to help customers easily recognize their products or lines in different price ranges. The above two photos show Chad Valley’s packaging in the 1920s, and the updated style of box that they introduced sometime in the early 1930s. Note the swooping letter S in the second photo. It seems to reflect Chad Valley’s characteristic gently looping cutting style that created gracefully interlocking pieces (as distinct, for example, from the larger G.J. Hayter Company’s characteristic style of rather straight grid cutting with relatively small interlocking connectors.)

Chad Valley’s own puzzles included a wide range of types of artwork that were popular at that time. That included rural landscapes and nostalgic genre paintings as well as images celebrating sports (including fox hunting), technology, and patriotism. (You can see this range displayed on David Shearer’s Jigasaurus website.) Unlike the other companies they do not seem to have been big on fine art images or large puzzles, and they did not join the trend of including figural pieces in their cutting.

Puzzles of the Royal family and occasions were always big sellers for the company and they had another special reason to feature that topic. Chad Valley had exclusive permission to make dolls to make dolls depicting princesses Elizabeth and Margaret Rose. In fact, Chad Valley toy were indeed among the young princesses favourite playthings. And in 1937 the company was given a Royal Warrant as toymakers to the Queen (who was a lifelong jigsaw puzzle enthusiast.)

Despite that prestigious royal recognition, and being one of the largest and best of the factory jigsaw puzzle makers, the company’s puzzle profits were waning in the latter 1930s. That was due to rising labour costs and increased competition from so many other makers who had started up during the early-depression boom times, but perhaps most importantly, the public’s recreational attention was turning to other hobbies.

Chad Valley could have saved costs by allowing its cutters to use the more efficient grid cutting pattern that its arch-rival G.J. Hayter had pioneered. (You can read my essay about the history of that company here.) In that style the cutters make long continuous cuts (with periodic meanders to make connectors) across the the puzzle, and then make similar long cuts up and down that cross the horizontal cut-lines. This produces a rectilinear grid with a connector on each side of every four-sided piece. The result is a fully interconnected puzzle that is much cheaper to make than puzzles with a wide variety of piece shapes.

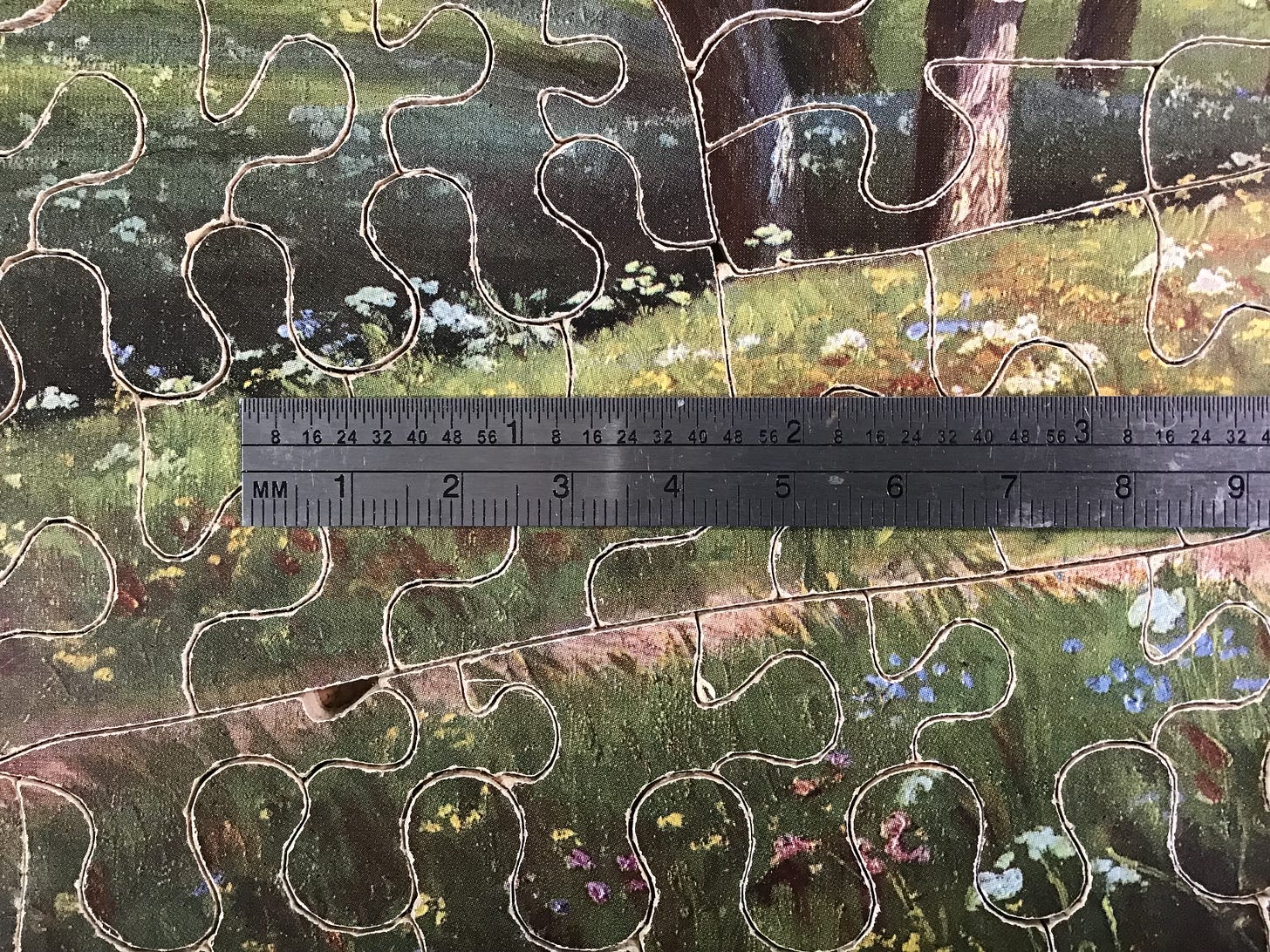

As you will see below, Chad Valley has a loopy cutting style in which cut lines very rarely cross each other, resulting in varied and interesting piece shapes. Chad Valley refused to compromise by dumbing down its cutting to cut costs, although they did reduce the number of pieces in their own various lines - for example their 2/6 puzzles went from 200 pieces down to 150. That lowered their costs somewhat but it did not stem the tide of declining sales. In fact, in a world that was slowly recovering from the Great Depression perhaps people resented paying the same price for puzzles with fewer pieces.

Then came the World War II. Unlike during the first War, when Chad Valley’s toy production boomed, in 1939 English industry went onto a full war-production footing. According to Tom Tyler’s very informative book British Jigsaw Puzzles of the 20th Century when discussing the company:

The Second World War brought a halt to puzzle production and it is interesting to note the company’s output during the war years. The woodwork factory produced items ranging from small instrument cases to boxes for gun barrels, from hospital tables to tent poles. . . . Children’s clothing was made in the soft toy factory, and charts in the printing works. By arrangement with the government, one factory staffed by the firm’s oldest employees, continued limited production of games and toys, including jigsaw puzzles for military hospitals together with draughts, solitaire, chess and dominoes for use by the Forces all over the world.

After the war Chad Valley faced a double challenge. The war had disrupted all business and the costs of wooden jigsaw puzzle production were prohibitive. The company had experimented with card puzzles but were not able to make the necessary investment in large presses for the manufacture of cardboard puzzles. In the immediate post-war years some wooden puzzles were produced but, by the early 1950s, jigsaw production had ceased.

Since its beginning Chad Valley had been a private family-owned and run company, but in 1950 it issued shares to raise more working capital. That backfired. Being a public company made it susceptible to unfriendly take-overs, first by Palitoy and then in turn by General Mills. In 1984 Hasbro acquired the rights to use the Chad Valley name and began to license its use for various products. In the 1990s cardboard puzzles began to appear bearing the Chad Valley name, but I don’t know where they were manufactured and as far as I know they are no longer being made.

You can find more information about the history of the Chad Valley Company here, here, and here.

Royal Route to the West

Maker – Chad Valley Co. Ltd (Harborne England, near Birmingham)

for the Great Western Railway Company

Made from 1933-’37

207 pieces; no figural pieces 10½” x 18½” (5.9 cm²/pc) 4½mm 3ply

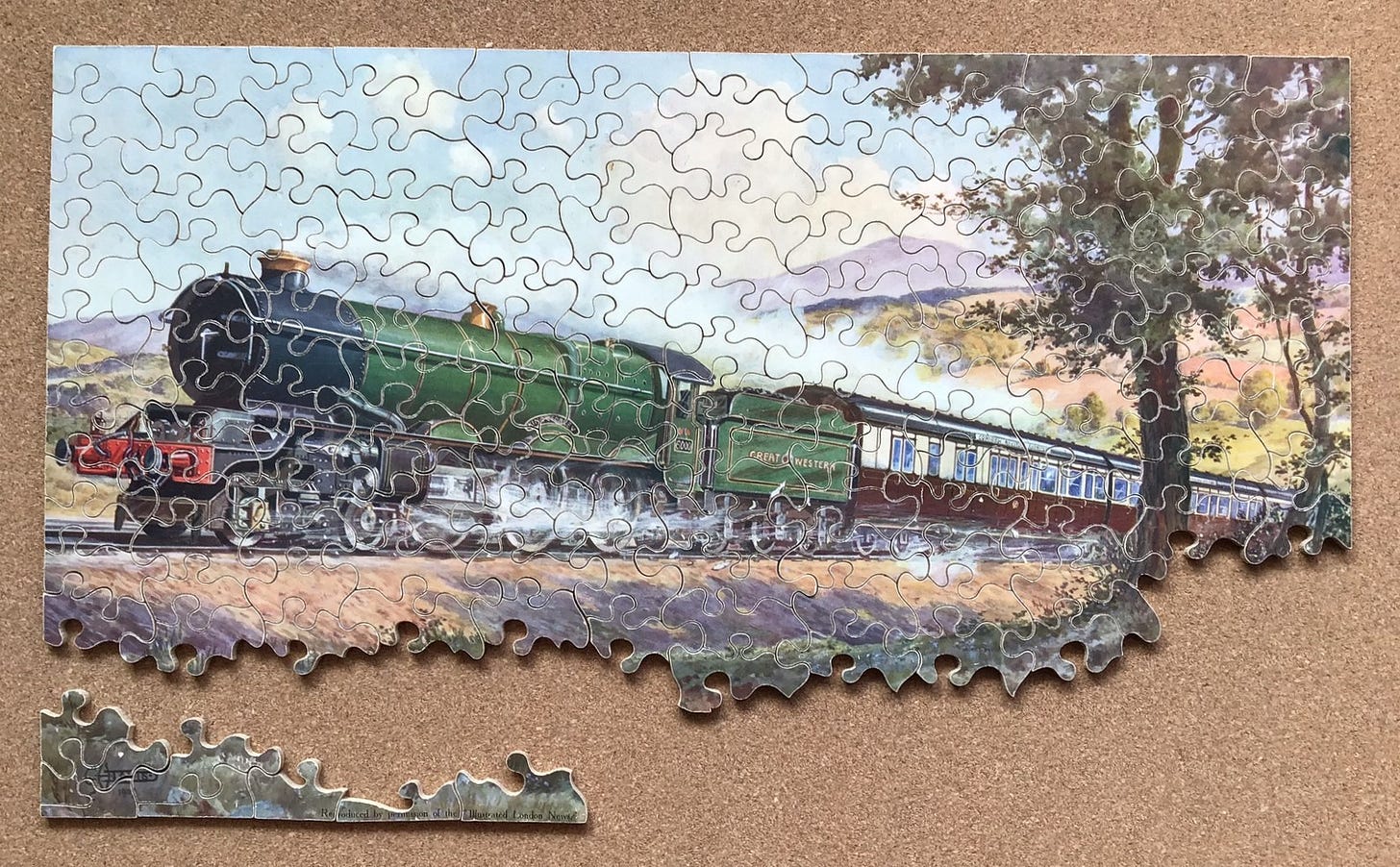

This was my first puzzle made by the Chad Valley Company. As you can see in the above photo the printing is quite bright and it has have that swirling non-grid cutting style that you know I like. The puzzle has no figurals, but frankly, sometimes I appreciate a break from whimsy-laden puzzles. Because of the free-flowing loopy cutting each piece in this puzzle seemed like an abstract figural piece. It isn’t apparent in the photo but at 10½” x 18½” this is a fairly large puzzle for one that only has about 200 pieces. The large pieces 1/4” thick pieces have a very rich tactile feel.

With only 207 pieces, this puzzle was quite easy to assemble although I got considerable enjoyment from seeing and handling the baroque shapes of the pieces. I began with the straight lines in the image and distinctive colours of the train itself and I worked out from there:

This puzzle is from Chad Valley’s collaboration with the Great Western Railway and it features an image of the first engine in that railroad’s next class of top-speed locomotives – named after the then-reigning monarch no less.

King George V was a very popular sovereign and this locomotive was clearly the most powerful locomotive in England by any measurement standard when it was introduced. (The Flying Scotsman remained the fastest in regular service because it ran over relatively straight and level tracks while the GWR’s routes to the west of England included more hills and curves which required the train to run slower. If there had ever been a side-by-side race between the Flying Scotsman and King George V (the locomotive, not the monarch) there is no question which would have won!)

This is one of several Chad Valley GWR puzzles that featured images of the King George V. The one on this puzzle is a 1929 painting by George Horace Davis (1881-1963), an acclaimed technical illustrator who was the long-time lead artist for the Illustrated London News.

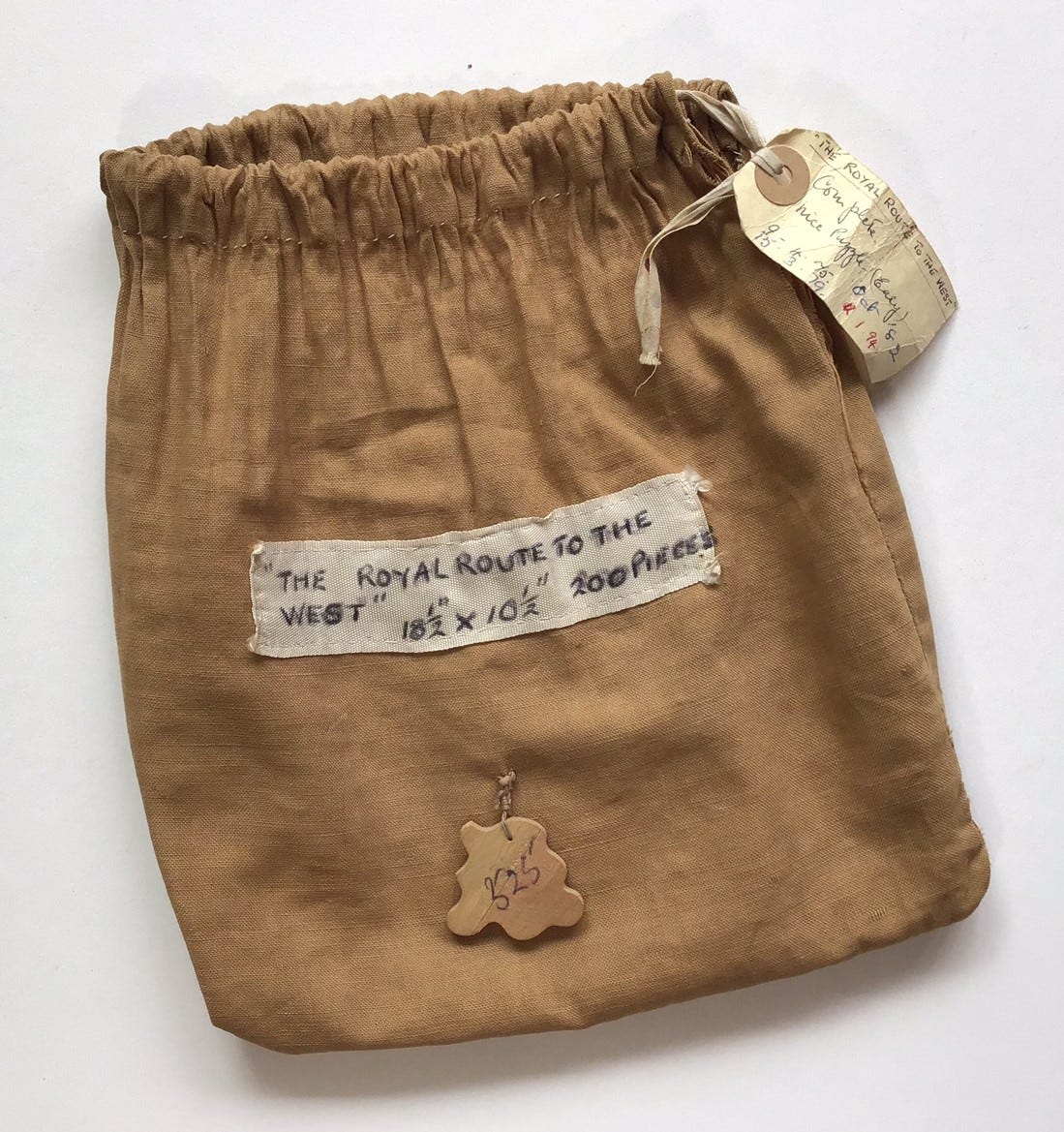

Chad Valley’s GWR puzzles are highly-sought collectors’ items among age-of-steam train fans and puzzle-folk alike. My 7 year-old grandson has train-brain and I have been out-bid in many auctions trying to get one. I was able to afford this puzzle only because it doesn’t come with its original box. The already-vintage jigsaw puzzle was repackaged in the 1970s by an unnamed British jigsaw puzzle library.

[Digression about puzzle clubs: Puzzle clubs or libraries were a business model that began during the jigsaw jag puzzle craze of the Great Depression. Independent home-workshop puzzle makers would supplement their sales by renting out their jigsaw puzzles. That led to accepting puzzles made by other cutters in trade for a store credit, thus expanding the number and styles that they had to offer. While they were usually called clubs or libraries they were actually small private businesses.

This puzzle was bagged up by the puzzle library in the 1970s. At that time the only Depression-era wood puzzle manufacturer that was still in business was G.J. Hayter (Victory brand) and “jigsaw puzzle” pretty much meant die-cut cardboard ones. Those of course are too fragile for very many assemblies and therefore not suitable for the puzzle library model of business. New wood puzzles were still being made by a few individual craftspeople, but like today, hand-cut puzzles were quite expensive to buy and out of reach for most people. Some British puzzle-makers (who had the technical skills to make replacements for lost, broken, and dog- or cat-chewed pieces) survived by continuing to run puzzle clubs or libraries.

With the advent of laser-cutting, wood puzzles have a made comeback on both the affordability and popularity fronts, but they are still very expensive compared to cardboard. For that reason the business model of wooden puzzle clubs is also making a comeback, although the current format involves national organizations that deliver their puzzles by mail rather than by local pick-up or hand delivery.

The United Kingdom still has the longstanding nation-wide British Jigsaw Puzzle Library, established in 1933, with its collection of over 3000 hand-cut puzzles. Another format has evolved there too that has been enabled by social media. I know of it because of another Facebook group of which I am a member called British Wooden Jigsaw Puzzle Group. It was established to provide a vehicle for buying, selling and trading used puzzles but soon also became a means for organizing “Travelling puzzles.” Such puzzles are ones that are donated by individuals or companies to be freely passed along from person to person by hand or by mail. People sign up in the group to be future recipients and the only cost is that of mailing the puzzle forward. Currently they have at least 20 wood and acrylic puzzles in circulation that way.

The leading puzzle library in the US is the Hoefnagel Wooden Jigsaw Puzzle Club, established as a spin-off by Artifact Wood Puzzles, one of the leading laser puzzle-makers. Also in the US, the Waterford Puzzle Company, whose cutter/designers make some of the finest hand-cut puzzles around, has established a puzzle rental program as has Stave Wooden Jigsaw Puzzles who make the world’s most expensive ones (and their rental prices reflect that.)

Canada doesn’t have such a commercial puzzle-library, a rental program or travelling puzzles yet and I’m not holding my breath expecting any – our domestic postage costs are much higher than those in Britain or the US. End of digression]

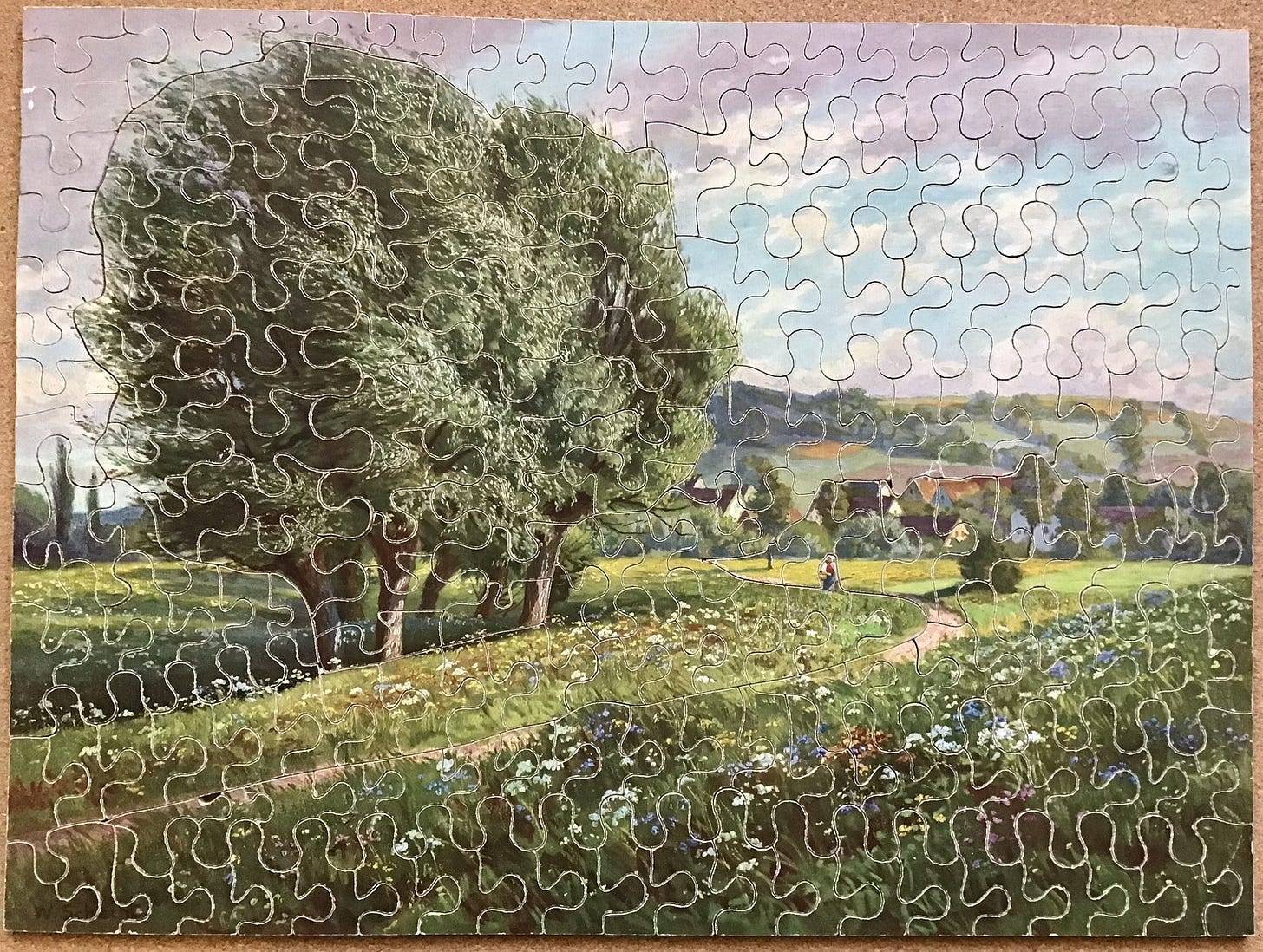

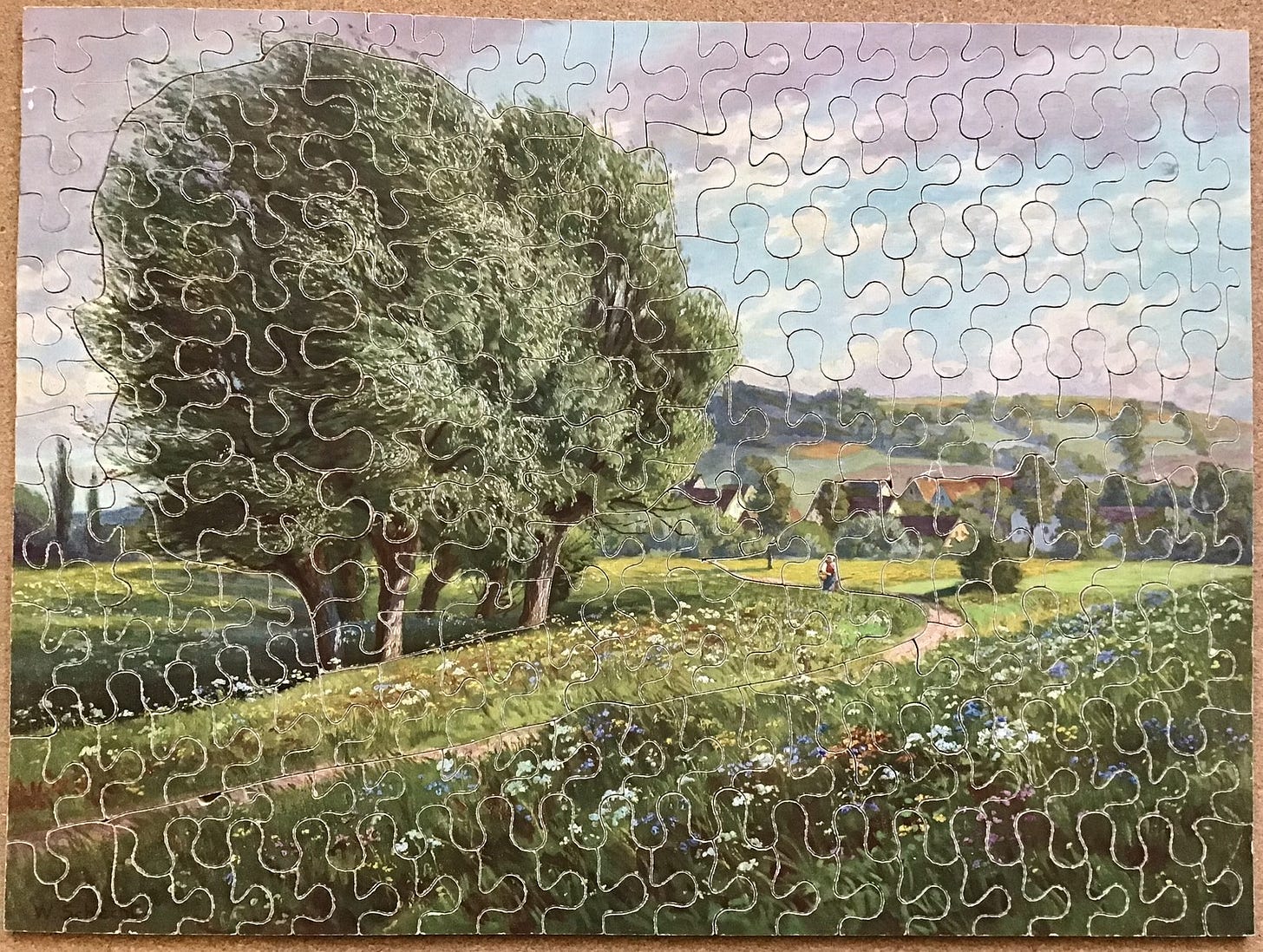

Sweet Summertime

(Note: This puzzle has a replacement piece. See if you can figure out which one it is. I’ll give you a clue at the end of of this essay.)

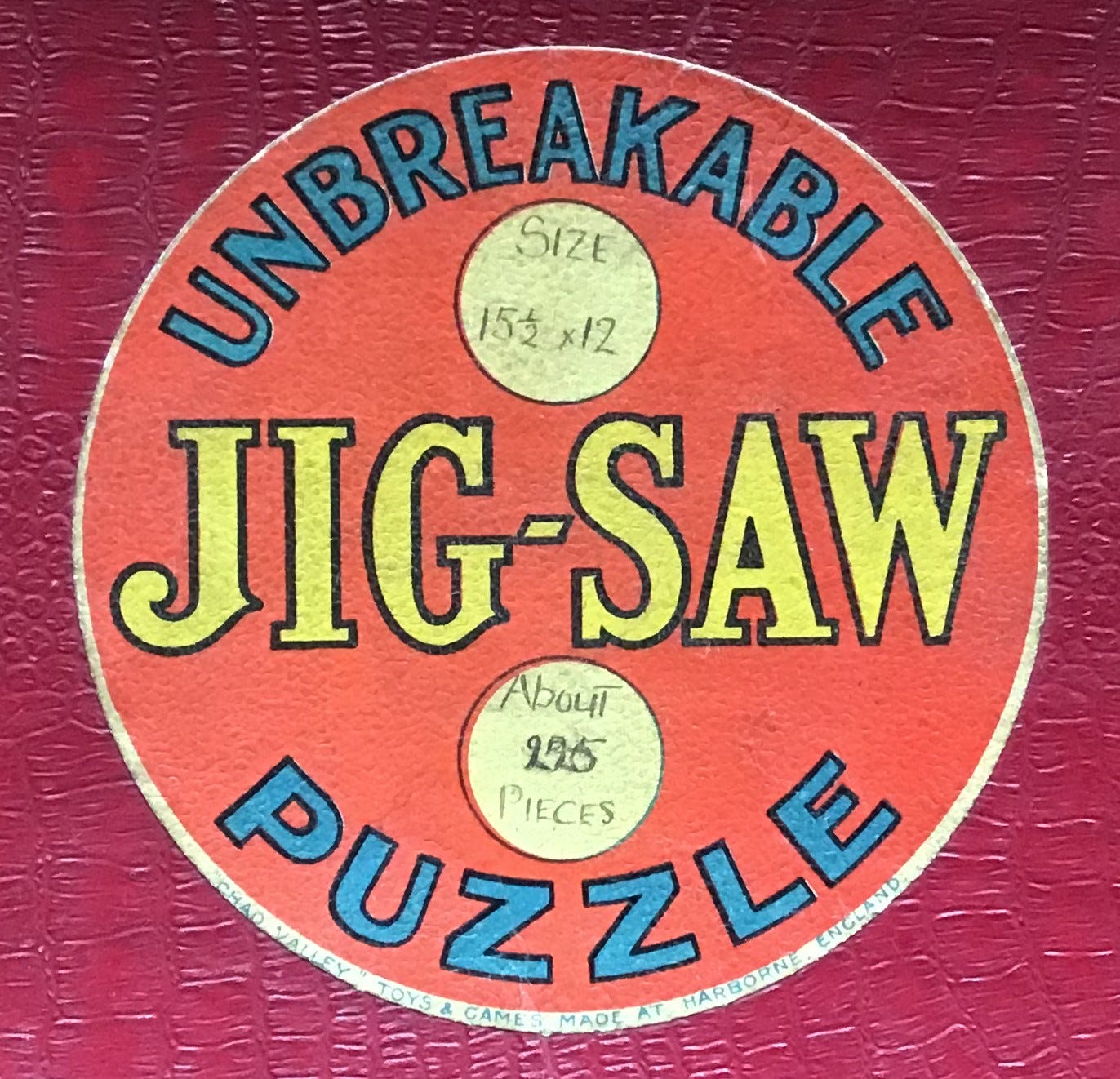

Brand – Unbreakable Jigsaw Puzzle (made by Chad Valley Co. Ltd)

Made sometime in the 1930s

188 pieces; no figurals 11½” x 15½” (5.9 cm²/piece) 4 mm 3ply

Sweet Summertime was also made by Chad Valley, as the label says in very fine print, but I don’t think this is a Chad Valley line of puzzles. It appears to be one of those that were made by the company under contract for a department store or a distributor. The name “Unbreakable Jigsaw Puzzle” does not seem to be as much a brand name as an intended descriptor of the product inside of a very fine box.

This was more challenging than I had expected from a puzzle of its size. Since it was made by Chad Valley I had expected its looping interlocking cuts. But I did not noticed in the eBay images when I bought it that it also includes some colour line cutting (or sometimes just called line-cutting.) This type of cutting is not typical for Chad Valley.

Besides the extra difficulty created by cutting along the places where colours in the image change, such cuts do not interlock. That makes this an only partially interlocking puzzle. Many parts of it assembled more like an old-fashioned push-fit puzzle, requiring extra care not to nudge the pieces and greatly adding to the difficulty of moving sub-assemblies. Not that I am complaining, mind you! The line cutting made this small puzzle both more challenging and more fun than its drab predominantly green image and cloudy blue sky otherwise would have been.

The image is an oil painting by the German artist Wilhelm Schacht (1872-1951.) Schacht identified himself as a follower of the Barbizon School even though that romantic landscape painting movement had mainly thrived in the 1830s-60s, before he was born. Participants in the Barbizon School had included Jean-François Millet, Camille Corot and Théodore Rousseau.

A major characteristic of the Barbizon School is that they considered nature and the landscape itself as being a suitable focus for painting and not simply as a background for the subject matter. Their paintings depicted a realistic portrayal of the scene but were executed with loose brushwork and softness of tonal qualities and form. The Barbizon School participants all lived in and around the town of Barbizon, on the edge of the Forest of Fontainebleau, sixty kilometres southeast of Paris, and considered themselves to be followers of the English painter John Constable. They critiqued each other’s works and learned from each other, and all tended to resist the mainstream government-backed Salon de Paris’ standards for what constituted fine art.

The next-generation movement of French avant-garde painters, the Impressionists, acknowledged their debt to the Barbizon School. They were inspired by its perspective of nature itself as subject matter and style of portraying it, its collaborative approach of learning from one another, and its resistance to the dictates of the Salon. All of those things became characteristics of Impressionism and they were all modeled after Barbizon.

But Wilhelm Schacht was not avant garde, nor was he French. His career was entirely in Germany, and it began after Barbizon itself had fallen out of fashion in artistic circles. In fact, his career was mostly after even impression itself was no longer considered to be avant-garde. But although he continued to self-identify with the Barbizon movement over time his paintings took on more Impressionist characteristics. The dates of his paintings are largely unknown but when his they are sold at auction now it is those works, not his probably-early romantic paintings like this one, that tend to sell for the highest prices (up to $2000 USD.)

But back to the puzzle. Aside from the line-cutting, what I found most interesting about this puzzle were oddities about its packaging and marketing. According to David Shearer, who has considerable expertise as the former proprietor of the former proprietor of the British Jigsaw Puzzle Library (referred to above), as the President of the BCD (The Benevolent Confraternity of Dissectologists), and as the person behind The Jigasaurus website, such puzzles appear to have been made by Chad Valley for only a brief time in the 1930s. I don’t know why a puzzle like this – especially one with line cutting – was sold largely incognito and under such a bland brand name, but at the same time packaged in a very high quality box reminiscent the packaging used for Raphael & Sons’ high-end Zag-Zaw puzzles.

The only thing that would make this puzzle “unbreakable” is that it was made of wood instead of cardboard. But wood ones were still the most common kind of jigsaw puzzle back then. And in those days, except for the occasional cutting error that put too narrow of a neck on a connector or too fine of a point on a piece, wood puzzles were not considered to be particularly susceptible to breakage. The only thing that would make this puzzle worthy of being called “unbreakable” would be if particular care had been taken to avoid cutting that created weak spots. But in fact this puzzle does have two places where small bits are broken off as shown in this photo:

The missing bits are not large, and they did not interfere with my enjoyment of the puzzle, but both breaks appear to have been the inevitable result of weak spots that were made in the cutting process. That seems like a very strange thing to do in a puzzle that was to be marketed as unbreakable!

An explanation of this being poor quality control in a factory where the workers were paid by piecework rather than hourly might seem to be confirmed by the fact that it has only 198 pieces while the box label promises “about 225 pieces.” I don’t know that this size claim is necessarily a purposeful exaggeration. But combined with the slight breakage that the puzzle exhibits those are exactly the kind of easily-discovered shortcomings that would be detrimental if the vendors wanted “Unbreakable Jigsaw Puzzle” to become a reputable brand name.

In any event, despite being inaccurate the name of this short-lived line of puzzles appears to be intended to distinguish these puzzles from the cheap cardboard ones. But the high quality box seems to be trying to place it in competition with top-of-the-line jigsaw puzzles rather than the cheap ones.

At the time, except for Chad Valley all of the other wood puzzle factory companies made various lines or series of puzzles for various price points. Sometimes the different lines had different brand names. The higher-quality more expensive puzzles (like Victory’s Artistic, and the J. Salmon Company’s Academy series) were aimed at upper-middle class people and higher. They were always packaged in tasteful, high-quality boxes.

This puzzle has such a box. It is made from thick and apparently archive quality cardboard (it hasn’t yellowed with age) that is covered with a rich red alligator-skin textured outer paper. In fact, it is the sturdiest and most elegant packaging that I have seen to date from the 1930s.

Besides the quality of the box itself is the fact that it doesn’t have a picture showing what the completed puzzle will look like. With traditional British class-consciousness, the people who could afford premium-grade puzzles were believed to be more discerning in their preferences for classier styles of artwork and demands for higher quality of fabrication and trickier cutting designs (for example, by including some line-cutting.) It was also believed that these discerning upper-class customers did not want to have an image to aide in assembly. In the 1930s almost all high-end puzzles from various makers, factory or artisan workshop, were sold without an image on the box or with only a very small one.

The puzzles for the lower classes, which of course included the cardboard ones, were sold in relatively flimsy boxes that almost always had an attention-getting large and colourful picture of the puzzle’s image adorning their covers. By the mid-1930s the boxes Chad Valley’s own branded puzzles seem to have been compromise with this dichotomy, with their covers featuring a small picture of the puzzle’s image. G.J. Hayter, on the other hand, followed the normal expectations. It used picture-less sturdy gold boxes for both their middle- and high-end puzzles, and large images dominated the tops of flimsy boxes for their lower-end ones.

Thus, although the brand name Unbreakable Jigsaw Puzzle seems to suggest that this line was intended to compete with the cheap puzzles, this box looks like it was designed to stand out on a department store’s top shelves as being in the same league as the best puzzles. I don’t have an answer for the contradiction but I have a few speculations.

One is that this was in fact a way that the Chad Valley semi-anonymously packaged its own factory seconds or one-off cutting experiments, which can be expected to have been priced inexpensively. But in that case the simple name “Wood Puzzle” on the label would have made more sense, as would packaging them in an inexpensive box.

Another speculation is that the vendor was trying to emulate the look of one-off puzzles hand-cut by independent artisans in home workshops. Independent craftspeople frequently branded their puzzles with something that sounded like a company name. The following photo is the packaging (hosiery boxes covered with wallpaper) of two small “Leisure and Pleasure” puzzles made by Enid Stocken, considered by many to have been one of the very best English puzzle-makers in the 1930s to ‘60s. But if that was the case why were puzzles made by the highly-respected Chad Valley company given such a low-brow name?

My third speculation is the most likely: Someone made a poor marketing choice (which might explain why Unbreakable Jigsaw Puzzle was a short-lived series.)

____

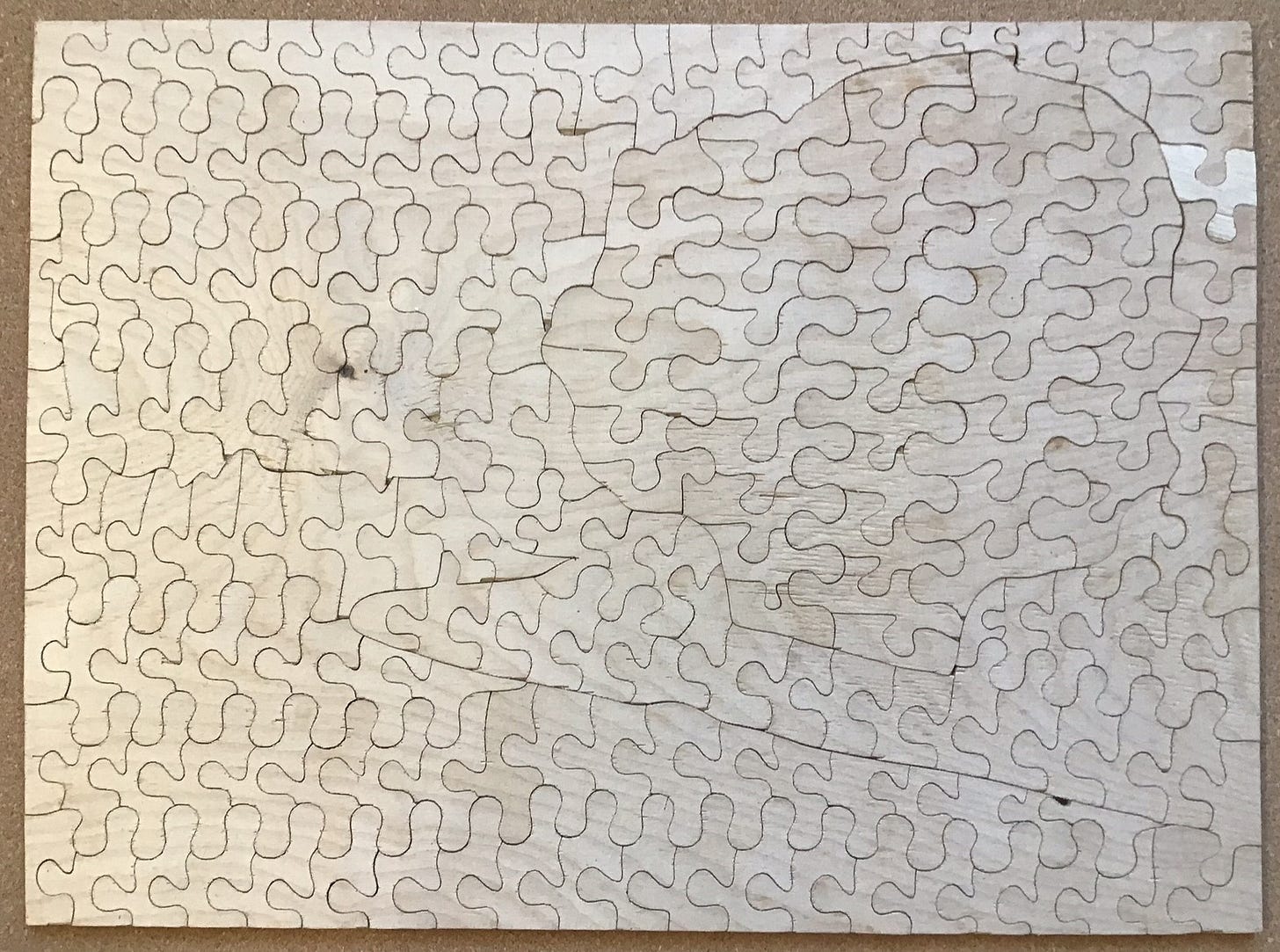

Here is the hint that I promised you in the digression about puzzle libraries regarding the replacement piece in Sweet Summertime. The following photo is the back-side of the puzzle. Remember that the back is a mirror-image of the front. Pretty well done replacement, eh!

As always, Bill, your research is impressive, as is your devotion to this hobby. I must admit, though, that I find the more present-day puzzles and their backstories to be the most engaging. Among the Chad Valley productions, I did like best "Royal Route to the West." I could see myself enjoying assembling and owning that one. I was also surprised by how large the Chad Valley operation became— that photo of their factory was something else! Thanks for your work.

Best regards, Greg