39. Vintage hand-cuts without whimsies; Part 1

Exploring jigsaw jigsaw puzzle cutting history and four examples of non-interlocking (push-fit) puzzles. Updated May 2025 (about 5600 words; 52 photos)

[Reminder: most of the photos in my postings are fairly high resolution and are quite zoomable.]

[Update: In May 2025 I added Gathering Water Lilies, another puzzle made by Peacock for Selfridges.]

Introduction

Interconnecting knobs are so ubiquitous in jigsaw puzzles these days, whether cardboard or wood, that most people think of them as being an inherent feature of this kind of puzzle. And since some companies call their whimsy-filled wooden puzzle creations “Victorian style” many people might think that whimsies and connecting knobs must have been abundant in old puzzles.

Actually, interconnecting knobs and whimsies only became common until the 1920s even though they had been included in a few puzzles in the 1800s. Before then, interlocking pieces had primarily been used for edge pieces to create a frame for non-interlocking ones in the middle, and good quality silhouette pieces were only found in particularly expensive ones. Before the advent of laser-cutting, incorporating figural pieces into a cutting design was risky: A mistake could ruin the whole puzzle. And cutting puzzles with effective silhouettes could only be done by the most talented and experienced cutters. Despite the tale that says they are called “whimsies” because they were included by the cutters “on a whim” they were carefully planned features of their puzzles.

This and the next newsletter feature vintage jigsaw puzzles without figural pieces that were mainly cut by workers in puzzle factories. After a brief introductory essay about jigsaw puzzle history this Part 1 focusses on puzzles that did not include knobs, and Part 2 will have ones that are interconnected. I will be sending out Part 2 about a week from now. Here is the Index for the two parts:

Part 1

Introduction

Jigsaw puzzle cutting history

An Interesting Story, made by William Peacock & Sons ca. 1908

Gathering Water Lilies, Made by William Peacock & Sons for Selfridges ca. 1914

A Sussex Village, made by William Peacock and Sons ca. 1910s

A Rough Sea, made by Raphael Tuck & Sons in the 1920s-’30s

Nativity Play, 13th Century, East Anglian Jigsaw Club 1960s-’70s

Conclusions regarding push-fit puzzles

Part 2

Introduction and more about puzzle history

Don’t Make a Noise, made by A.V.N. Jones & Co. late 1920s - 1930s

Shiptime at Pangnirtung, made by the Joseph K. Straus Co. ca. 1940?

Autumn Harvest Stored Away, made by the J.K. Straus Co. early to mid 1930s

The Torbay Express, made by the Chad Valley Works ca. 1928

Coming up

Jigsaw puzzle cutting history

This short essay expands on the historical overview that I posted over two years ago in this newsletter. Jigsaw puzzles were invented in the 18th century as an educational tool for the children of the aristocracy and very rich people. They began with maps that were cut following borders to teach geography. Later, biblical and historical scenes and other educational or morally uplifting images were also “dissected.”

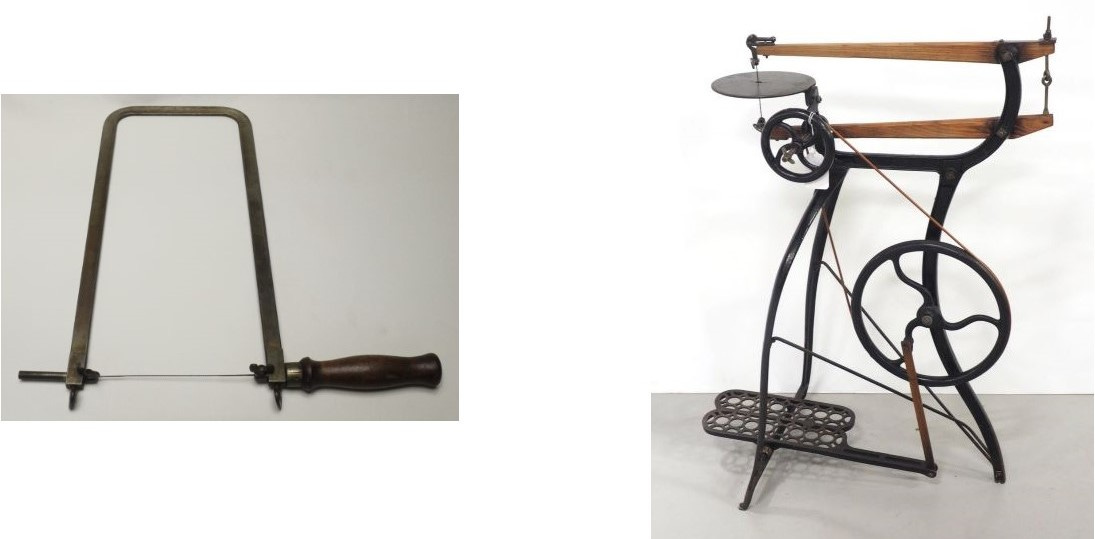

The substrate of the early puzzles were thin sheets of hardwood which were cut by highly-skilled craftsmen using fine bladed fretsaws. For jigsaw pieces to slide into place easily the saws needed to be kept perfectly vertical as the blade was moved up and down while the other hand kept the puzzle blank from moving. If the saw went out of vertical even by a little bit the pieces would not fit well.

In the mid-1800s the invention of the treadle scroll-saw enabled puzzles to be made more quickly and accurately. That tool had been invented in the mid-1800s to cut marquetry and the filigree-like architectural and furniture decorations that were popular during the Victorian era but puzzle-makers immediately saw their usefulness for their profession and began to use them.

Scroll saws enabled a stationary sawblade make perfect vertical cuts relative to a horizontal working surface, and because they were foot-powered both hands were available to feed the puzzle blank into the saw turning it to make the desired curves. This meant that less skill was required from the craftsperson: Anyone with good manual dexterity could be taught to be a cutter but the quality of that person’s work also depended upon having an artistic eye. Basically, although they are now electrified rather than treadle-powered, and much better saw blades and mechanisms to hold them are now used, modern scroll saws work exactly the same way.

As mentioned, at first jigsaw puzzles were just for children. It took over 100 years before less didactic pictures were dissected to provide recreation for adults, and another 50 years before the idea caught on. At first such puzzles were mostly sold as custom-made products (bespoke, as the Brits would say) from skilled craftsmen, and were still expensive and only popular among the wealthy. For most people, recreation time was limited to evenings six days of the week so I suspect the fact that only the wealthy could afford to have electric lighting may also have been a factor in that exclusivity. The name “jigsaw puzzles” had not become standardized at that time; they were usually called “dissected pictures”.

Because of their usefulness for builders and cabinet-makers, scroll saws were quite a common tool for wood-workers, and anyone who had a scroll saw could find a suitable picture and glue it to a thin board. Used scroll saws became readily and inexpensively available when the style of style of architectural decoration they were used for went out of fashion at the end of the Victorian era. In the late 1800s some woodworkers people began to make jigsaw puzzles as presents for their own family and friends, and some made puzzles to sell as a side-gig or while unemployed. Growth of this craft was slow at first but by 1900 interest in jigsaw puzzle, for adults as well as children, was increasing.

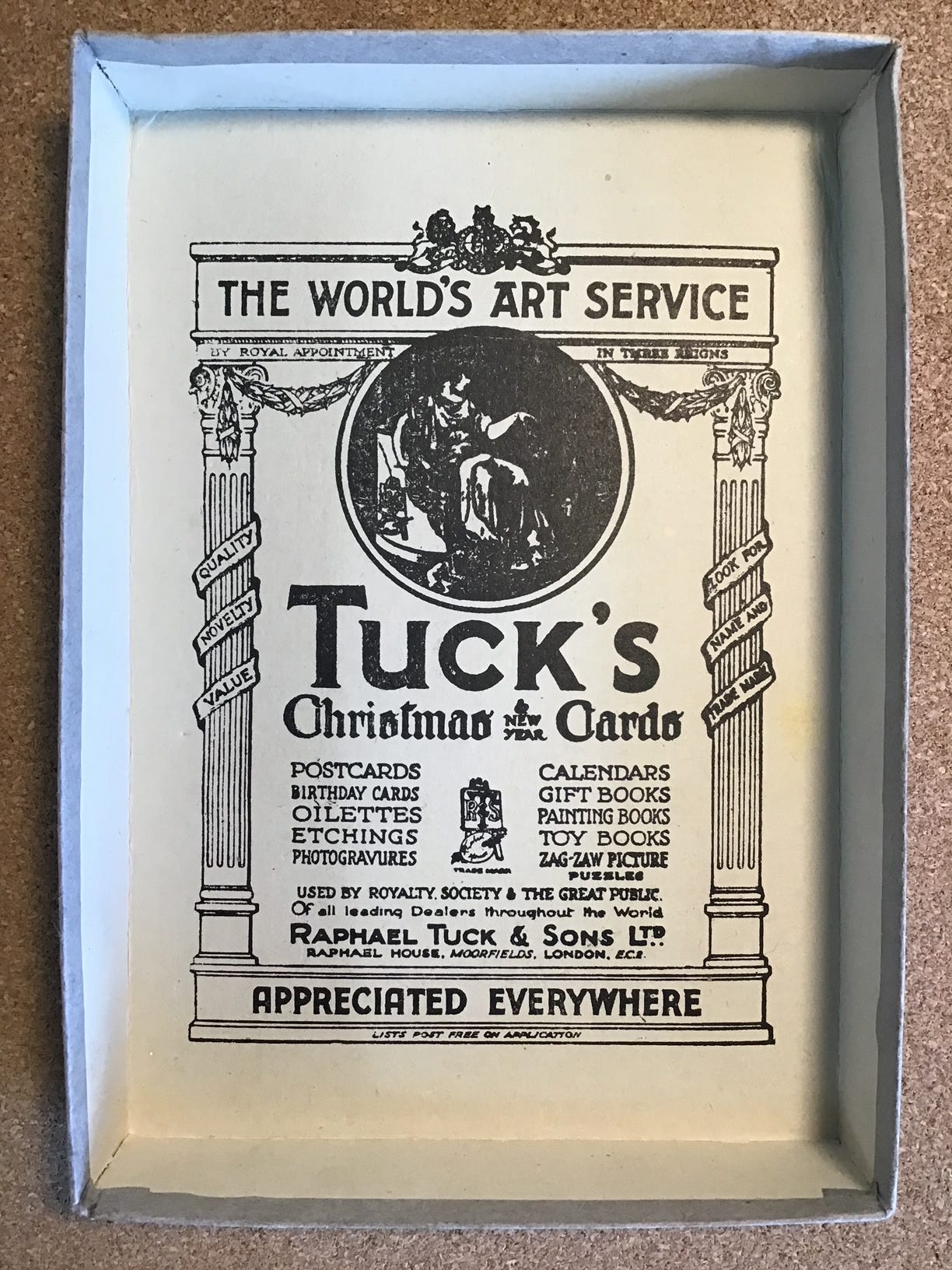

As demand for jigsaw puzzles from middle-class people grew entrepreneurs saw an opportunity to set up puzzle-making workshops that later grew into factories. As far as I know, the Raphael Tuck & Sons company was the first to do so, setting up workshops in Berlin and London as a side-line to their thriving printing business.

In the newly-emerging factory-workshop context the cutting of a puzzle was done by one person, with other people responsible for all of the other steps needed to turn an image printed on paper and a small sheet of wood and into a valuable finished product. These other steps included gluing the print onto the wood, sanding the cut pieces, and making the box in which to package them. Technically this wasn’t exactly assembly line work but division of labour, but it was more efficient than home workshops because this format required workers to only become skilled at their specific tasks. That, together with economies of scale, meant that puzzles could be made more efficiently and professional merchandising could be used to spur demand.

Cutting with a scroll saw was considered the main skilled job in such workplaces. The more highly skilled cutters who could do more ornate and imaginative cutting patterns were assigned to make puzzles for the companies’ more expensive series, and they were paid more. I don’t know about the other factory workers, but the cutters were paid by the puzzle with the rate dependent on how many pieces the puzzle had. Thus, cutters had an incentive to work quickly within their companies’ allowed cutting styles, but they still needed to avoid making any mistakes because a wayward cut could still ruin the whole puzzle.

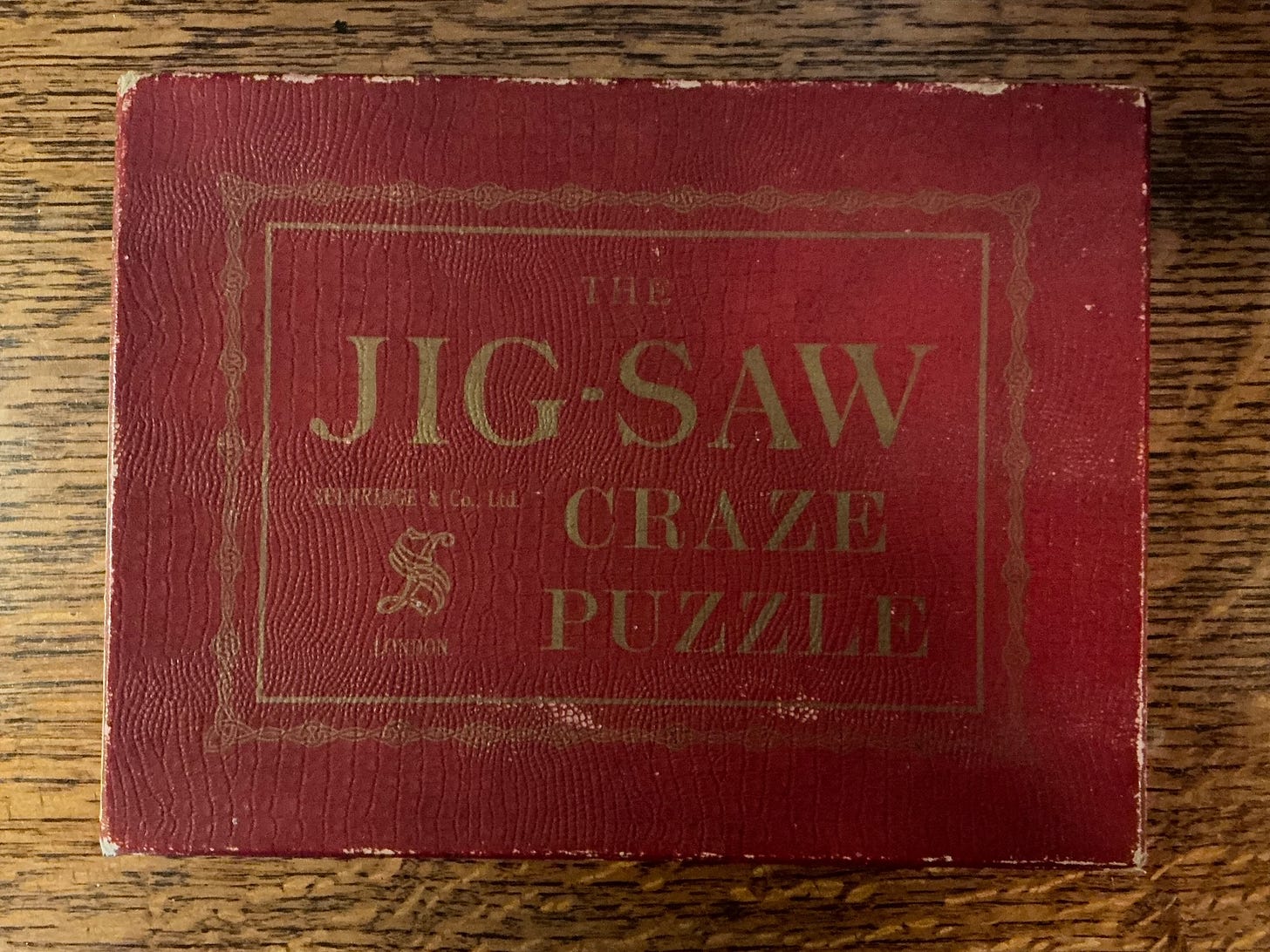

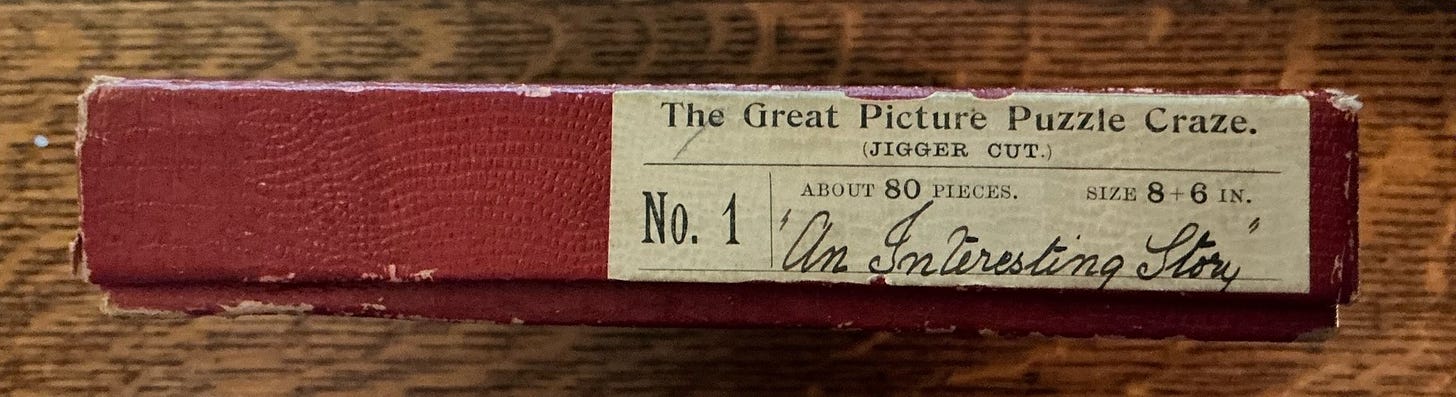

An Interesting Story, made by William Peacock & Sons

maker – William Peacock & Sons London, England

date – ca. 1908 push-fit cutting

74 pieces (count) 5¾” x 8” (14.5 x 20 cm) 3.9 cm²/pc 5mm solid walnut

artist – unknown

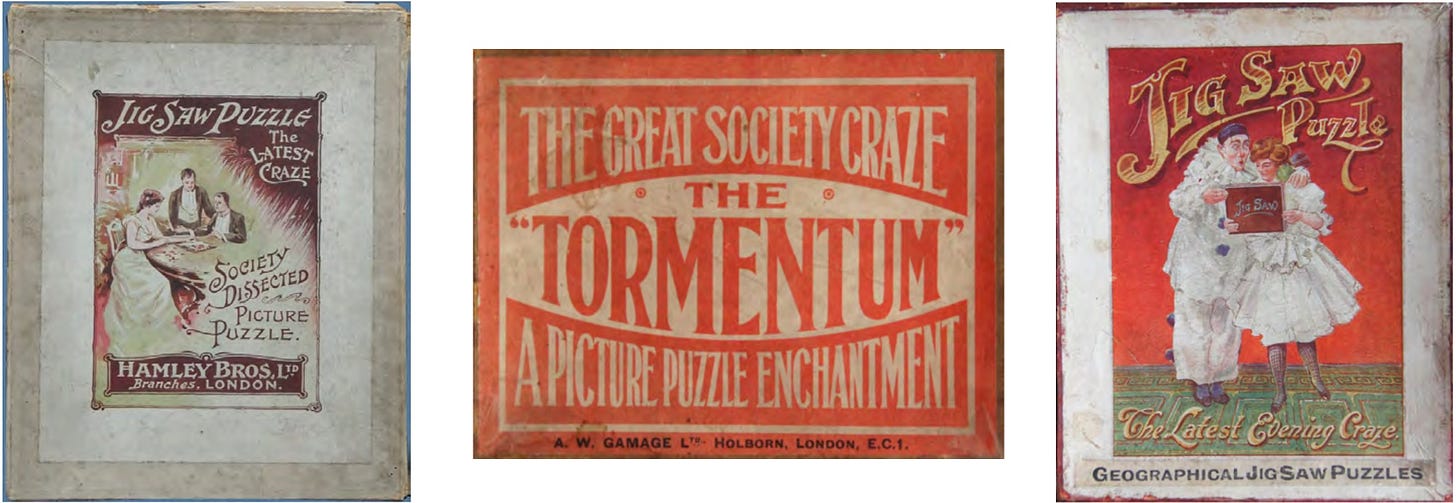

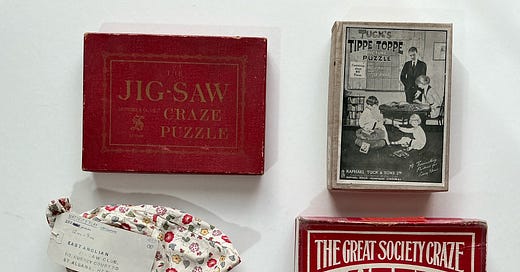

Beginning in about 1907, perhaps related to a major stock market crash causing a run on the banks and resultant recession, a fashion emerged among upper class people to assemble jigsaw puzzles with their friends as their centrepiece for after-dinner entertainment. Middle class people learned about this and began to emulate “better society.”

This new-found popularity of puzzles for adults coincided with the growth of jigsaw puzzle manufacturing by such firms as Raphael Tuck & Sons (who had branches in Berlin, Paris, London and New York), William Peacock and Sons in London, and the Pastime Puzzles branch of the Parker Brothers game company in Salem, Massachusetts. Dissected picture puzzles made by such firms became available as off-the-shelf products in high-end department stores, rather than as items that had to be commissioned from craftspeople. Thus the jigsaw craze, also known as the jigsaw jag, was born. It was big. In 1909 Parker Brothers ceased production of their board games to focus on trying to meet jigsaw puzzle demand.

This puzzle is from that era. In fact, it is probably from the early stage of the jigsaw craze because it is made with 5mm thick solid walnut wood. At the time, makers were transitioning to the use a new-fangled material called plywood because thin wood sheets are prone to warping, but not this puzzle.

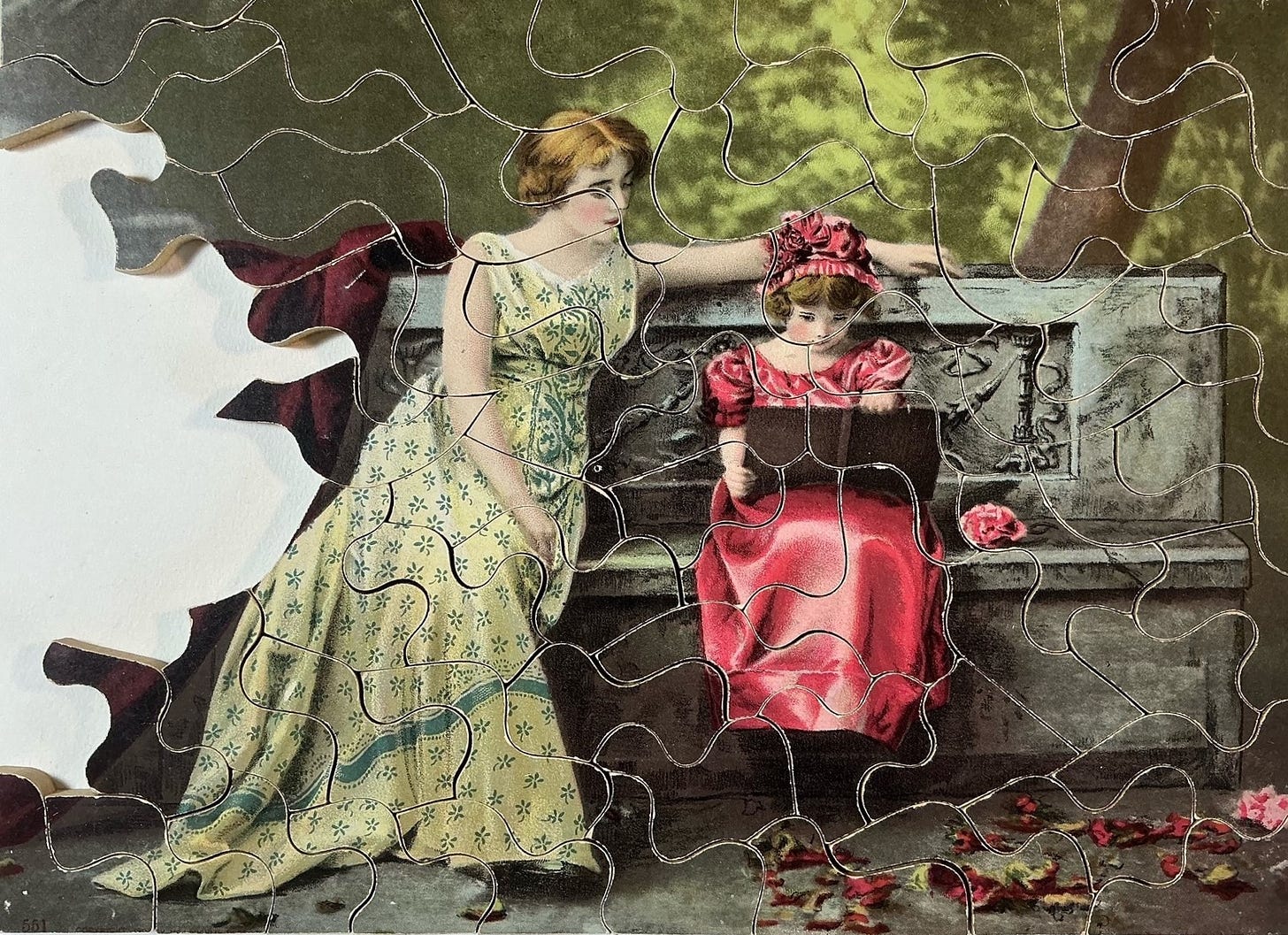

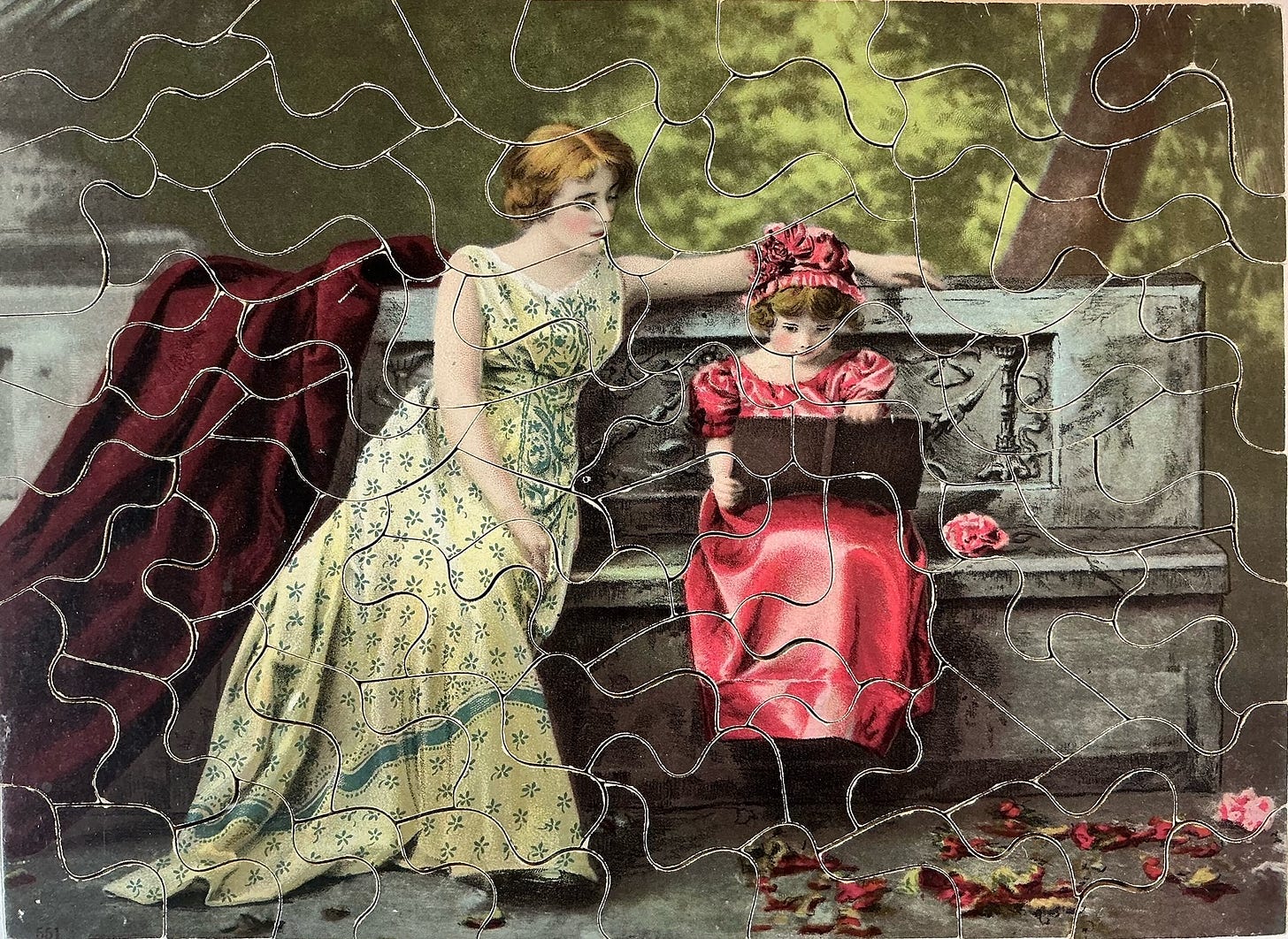

This is a very well-made puzzle indeed. My guess is that the wood has not warped because it had been kiln dried before it was cut into sheets. As you will see in the photos later the image colours are vivid and the paper was well glued down with no bubbles or wrinkles. After cutting, the sides of the pieces were sanded smooth leaving no saw-marks. As with all jigsaw puzzles back then, the style of cutting is push-fit because the technique of interlocking the pieces had not yet been invented.

I have not tried to develop a reference library for 19th century jigsaw puzzles (since I probably couldn’t afford any good ones anyway) but the maker that we know as William Peacock & Co. was originally founded in the mid-century by George James Peacock. According to this website:

… Peacock was a Baptist minister & a carpenter. He had managed the prominent children's education puzzle firm of Edward Wallis in London in the late 1830s and early 1840s. Then, in 1841, he took his family to Australia, where he was a policeman, missionary to the aborigines, school teacher and finally a postmaster. … He most likely went to the Australian gold rushes and according to Grace's Guide to British Industrial History, [in 1853] he "returned to the UK having 'made his pile' and opened Peacock and Co, making children's furniture, toys and ‘dissected maps’".

This website continues the story until the company’s end:

… In 1861, his son, William, took over the company, expanding it to become recognized as a leading producer of high quality wooden puzzles in distinctive wooden boxes with sliding lids. Cardboard boxes were introduced at the turn of the century.

William continued until 1910 when, on his death, the firm passed to his two sons William Edward and Albert Frank. William Edward was to turn the firm into a Limited Company in 1918, still working from the same address. Despite a major fire in 1926 the firm continued to expand, eventually outgrowing the old premises new ones were built at 175/179 St Johns Street in 1931. Peacocks introduced cardboard puzzles at that time and the toy side of the firm were producing an increasingly large range which now included Teddy Bears. William Edward Peacock retired in 1934 aged 64 with the firm being taken over by Chad Valley.

According to the introduction to Tom Tyler’s excellent British Jigsaw Puzzles of the 20th Century (self-published, 1997):

Peacock was a major producer of jigsaw puzzles during the last twenty-five years of the nineteenth century. He specialized in double-sided geography/history puzzles … Some had a map on one side … and a historical table on the other – kings and queens of England were a favourite. The puzzles, mounted on hardwood and in wood boxes, were of exceptional quality for the period.

But he goes on to say that Peacock’s 19th century puzzles were “somewhat dull”:

No-one could doubt their educational intention but there was no effort to provide a challenge or ingenious variations. Perhaps the fact that so many have survived intact indicates that once a child had done the puzzle it was put away and rarely attempted again. Nevertheless, because of his prolific output, Peacock signaled the way for jigsaw puzzles in the twentieth century.

See here or here for examples of Peacock’s double-sided educational puzzles. By the time of the jigsaw jag the company had branched out to offer more entertaining puzzles but not directly under the Peacock brand. As is common today, back then some merchants would commission companies to make products to their specifications to be sold under their store name. This puzzle is an example of such a product.

In this case the puzzle was made for the newly-launched Selfridges department store in London, which aspired to be as prestigious and up-scale as the famous Harrods store. Peacock & Sons is not mentioned on the box but I know that it was made by them due to this research. Selfridges was founded in 1908 so this may have been one of the store’s inaugural products. (I won’t go into it but the history of Selfridges is quite interesting in itself and the story of its founding is told in the television series Mr. Selfridge that appeared on PBS’ Masterpiece Theatre and is currently available on Netflix Other good starting places to learn more about the company’s history are from its Wikipedia entry and here.)

As with many fashions that crop up quickly it was not long before the jigsaw puzzle craze subsided. It reached its peak in 1909 but the phenomenon left many middle class and wealthy people with a lasting taste for jigsaw puzzling. Total sales remained much higher than they had previously been and they continued to grow through the 1910s and ‘20s. The craze that gave jigsaw puzzles momentum also foreshadowed a similar craze that erupted early during the 1930’s Great Depression, when stylistic and technical improvements as well as cut-throat competition greatly brought down the cost of puzzles and made them very popular among working class folks.

I bought this puzzle at auction from jigsaw puzzle collector David Shearer who hosts the very extensive and useful Jigasaurus website, and it is the oldest puzzle that I have so far. It wasn’t bought as a “frugal alternative” despite the fact that its push-fit style of cutting has definitely fallen out of favour for most assemblers. Puzzles of this vintage and by this maker are highly sought-after by collectors, but it is a small puzzle which they tend not to prefer (even though what we now call mini-puzzles have been around since the earliest days.) I was able to get this fine puzzle for £26.50 and I have really enjoyed assembling it. In fact, I have done so three times already, including just now as I write this:

This image does not depict a contemporary 1908 scene: It is a genre painting giving a nostalgic glimpse into upper class life during the Regency Period about 100 years earlier. The extravagance of the little girl’s attire supports this and because the woman’s dress seems to be cotton muslin it places her here as the girl’s governess rather than her mother. The bench they are sitting on appears to be on a gentry’s estate rather than a park bench. According to my friend Beth Skala, who is knowledgeable about such things, the dresses and hairstyles of both figures are authentic to the Regency period. This subject matter would have appealed to Selfridges’ target market of well-off British customers.

The look of rapt attention on the little girl’s face, and the fact that she is totally ignoring her companion, is very familiar to me. I often see that demeanor from my grandson Reid, but in his case he is usually staring at an iPad screen rather than a book.

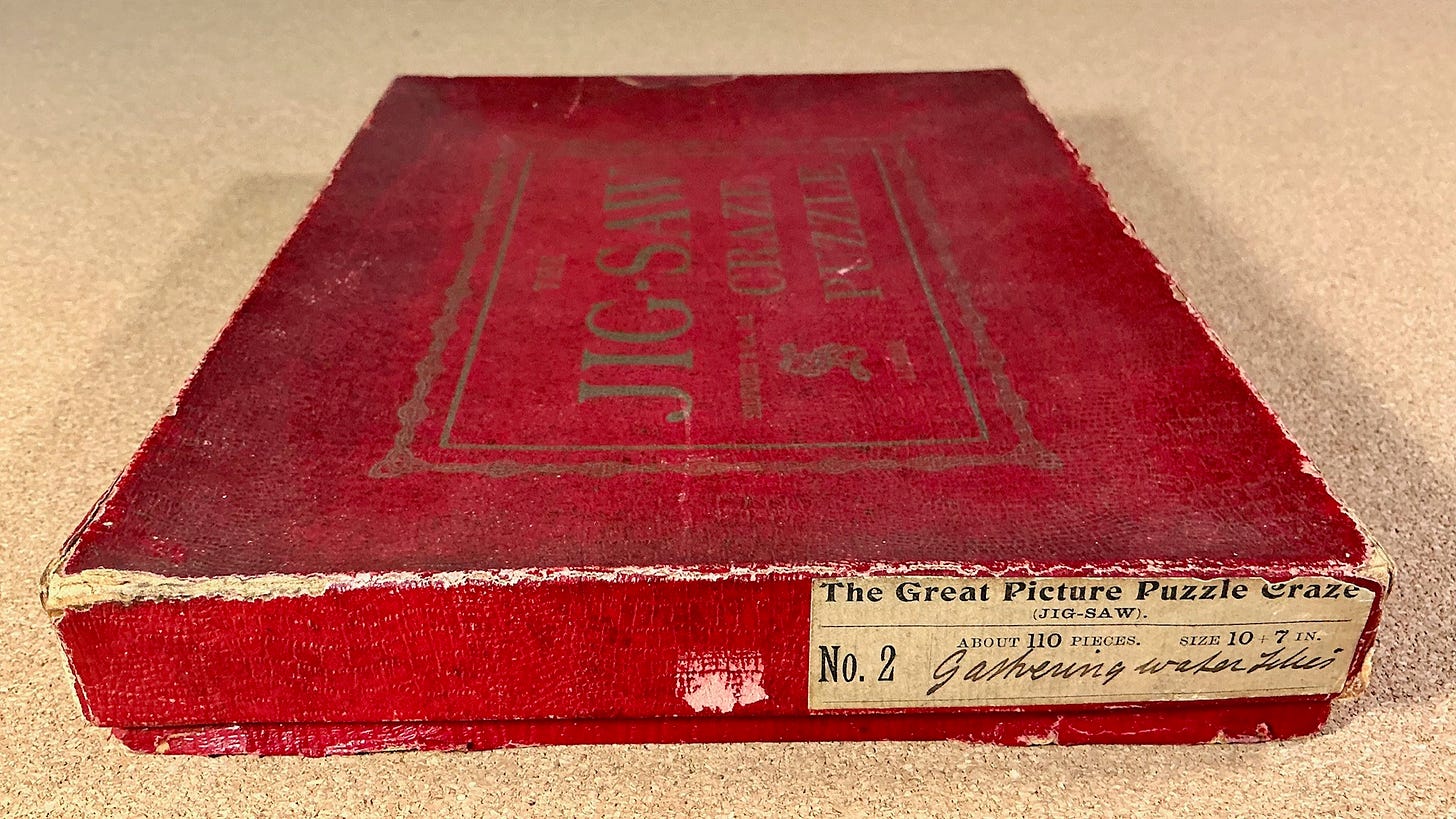

Gathering Water Lilies, made by William Peacock & Sons

maker – William Peacock & Sons London, England

date – ca. 1914 push-fit cutting

104 pieces (count) 17.5 x 26 cm (7” x 10”) ave. 4.3 cm²/pc 5mm solid walnut

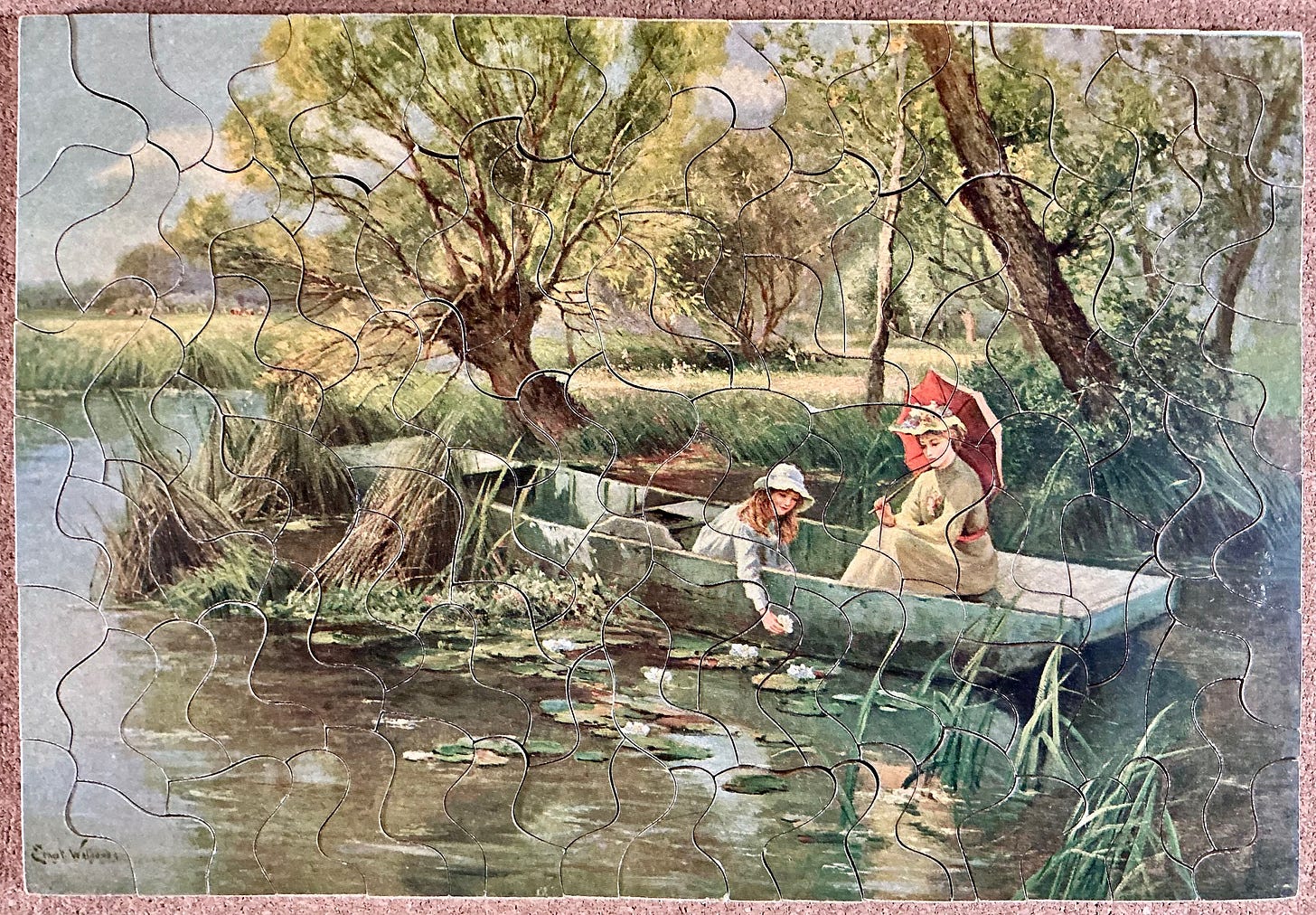

artist – Ernest Charles Walbourn (1872-1927)

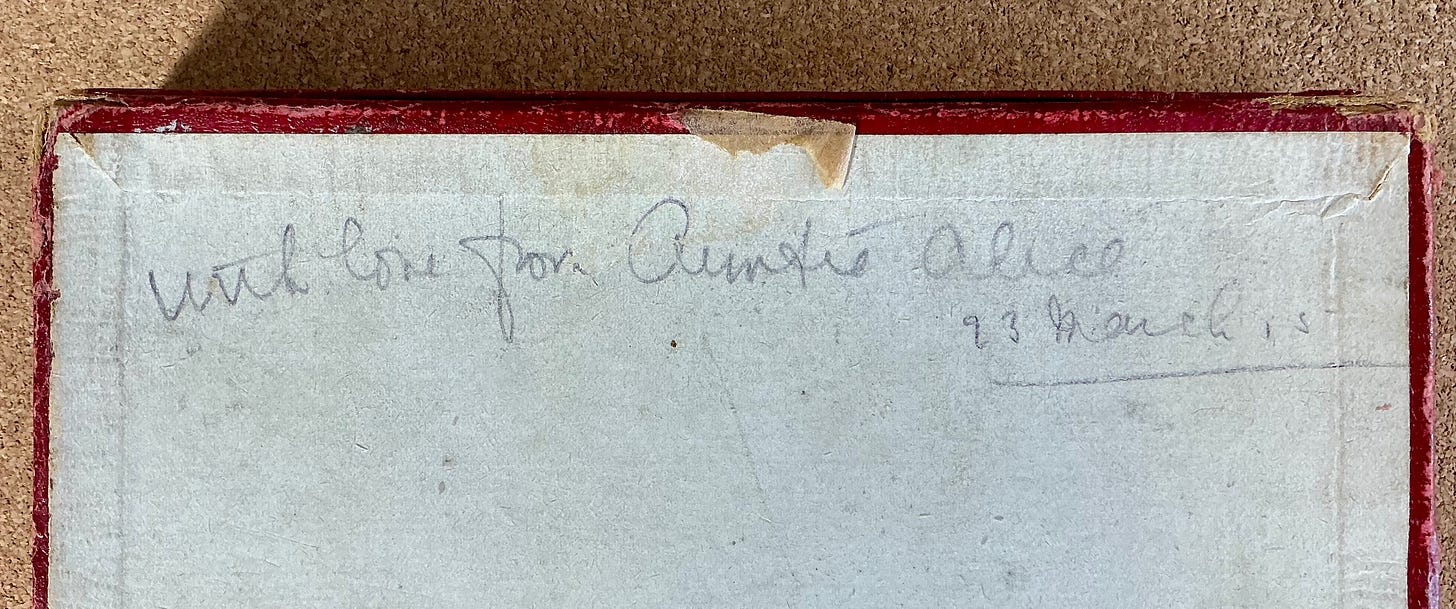

This is another “Jig-Saw Craze Puzzle” made by William Peacock & Sons for Selfridges. The label is slightly different than that of An Interesting Story, saying “Jig-Saw” instead of “Jigger Cut.” That suggests to me that it was made later, after jigsaw became standardized as the commonly accepted name for this kind of puzzle. That seems to be confirmed by a handwritten note on the bottom of the box that says it was given as a gift to someone by Auntie Alice in 1915:

The image is signed. It was painted by British artist Ernest Walbourn who specialized in rural genre scenes. According to this website:

Walbourn's work was in the classic tradition of Victorian landscape painting and earned him considerable popularity within his lifetime. He painted almost exclusively in oils and even his preparatory sketches were in this medium, such was his skill. His subjects were taken from the English countryside which he knew so well, and in particular from the Southern Counties, Wales and the West Country.

The cutting style of this puzzle seems to me to be nearly identical to that of An Interesting Story.

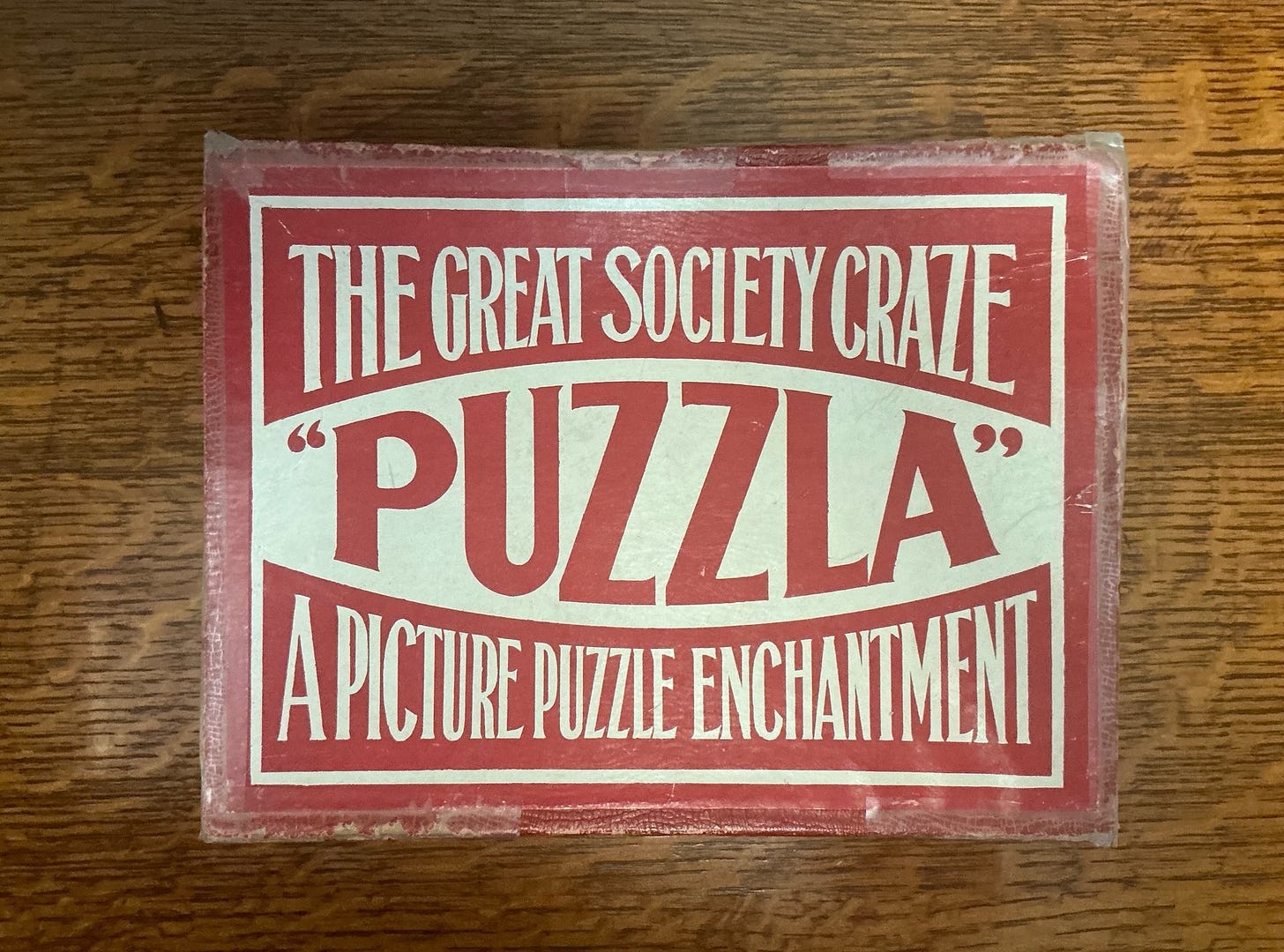

A Sussex Village, made by William Peacock & Sons

maker – William Peacock & Sons London, England

date – ca. 1910s? push-fit cutting

157 pieces (count) 12” x 7½” (30 x 19 cm) 3.6. cm²/pc 5mm solid walnut

artist – unknown

This is another puzzle made by William Peacock & Sons to be sold anonymously, but this time under its own generic “Puzzla” brand rather than identified with a particular department store. I don’t know why the company didn’t just sell them under its own name: As with An Interesting Story it is extremely well-made and has a substrate of solid walnut wood instead of plywood. Perhaps it was because the name “Peacock” was firmly associated with rather boring educational puzzles and the Puzzla brand as well as Peacock’s semi-anonymous (because it had a peacock as a logo) “Toys to Teach” brand were intended for recreation.

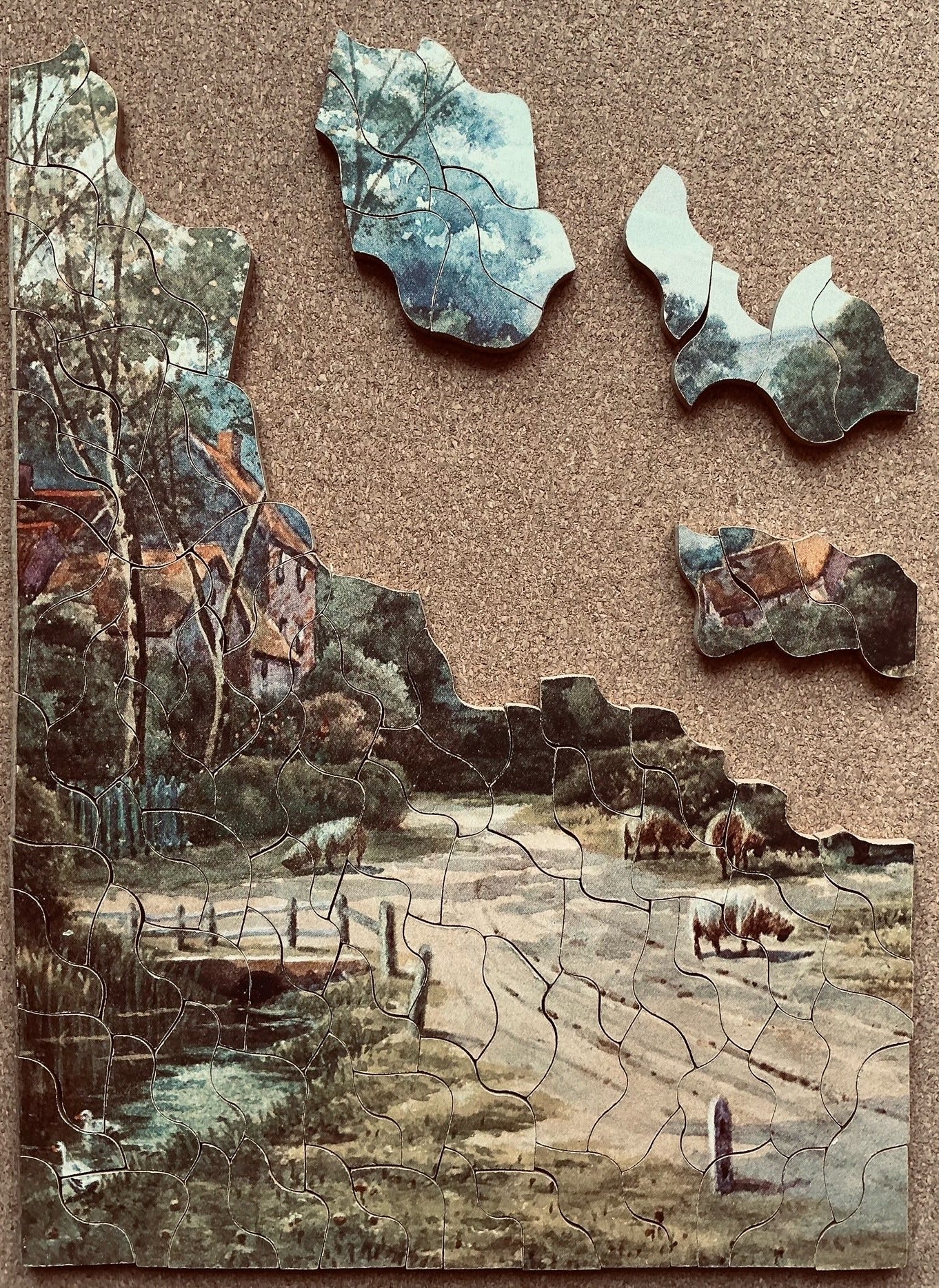

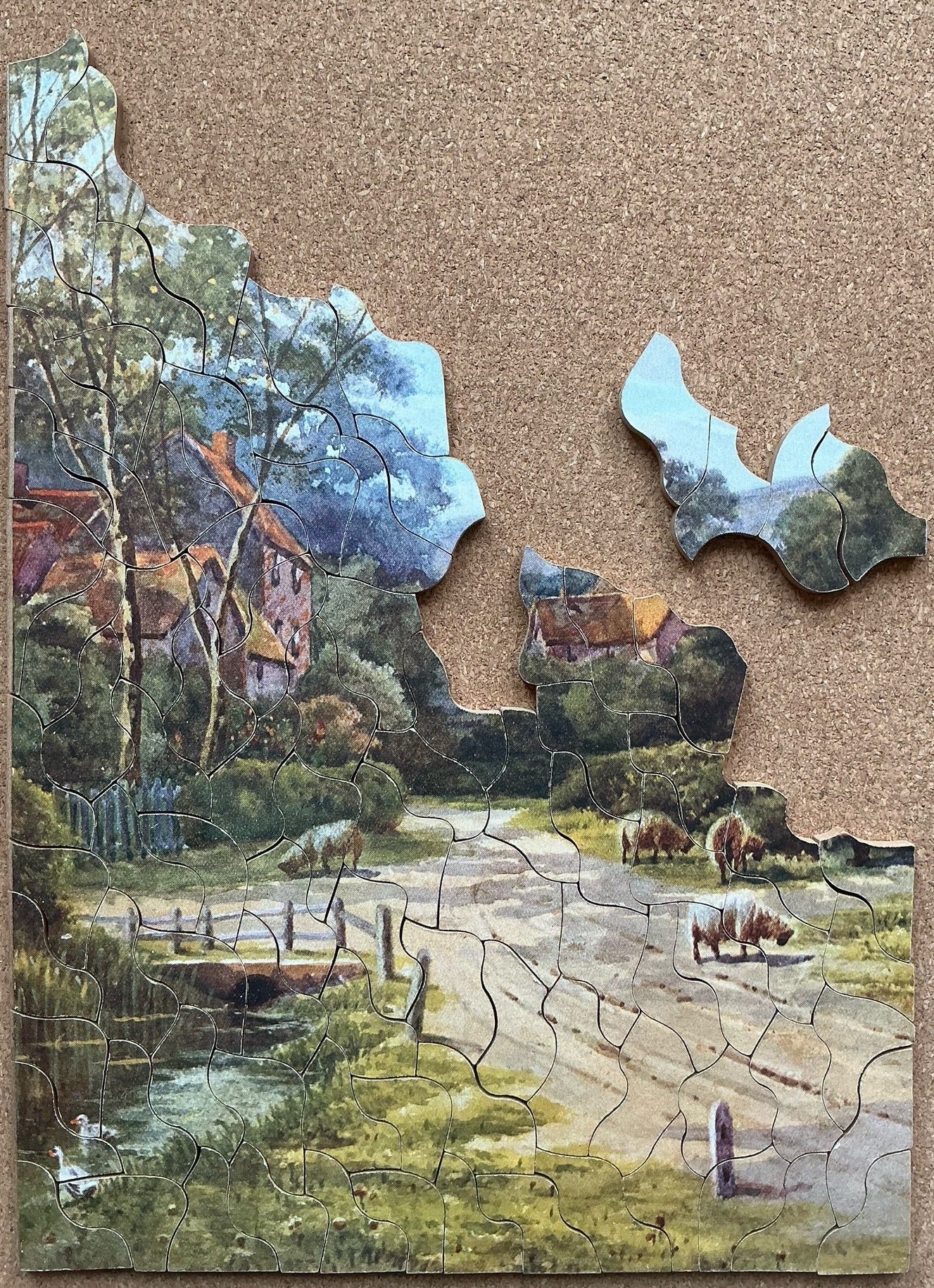

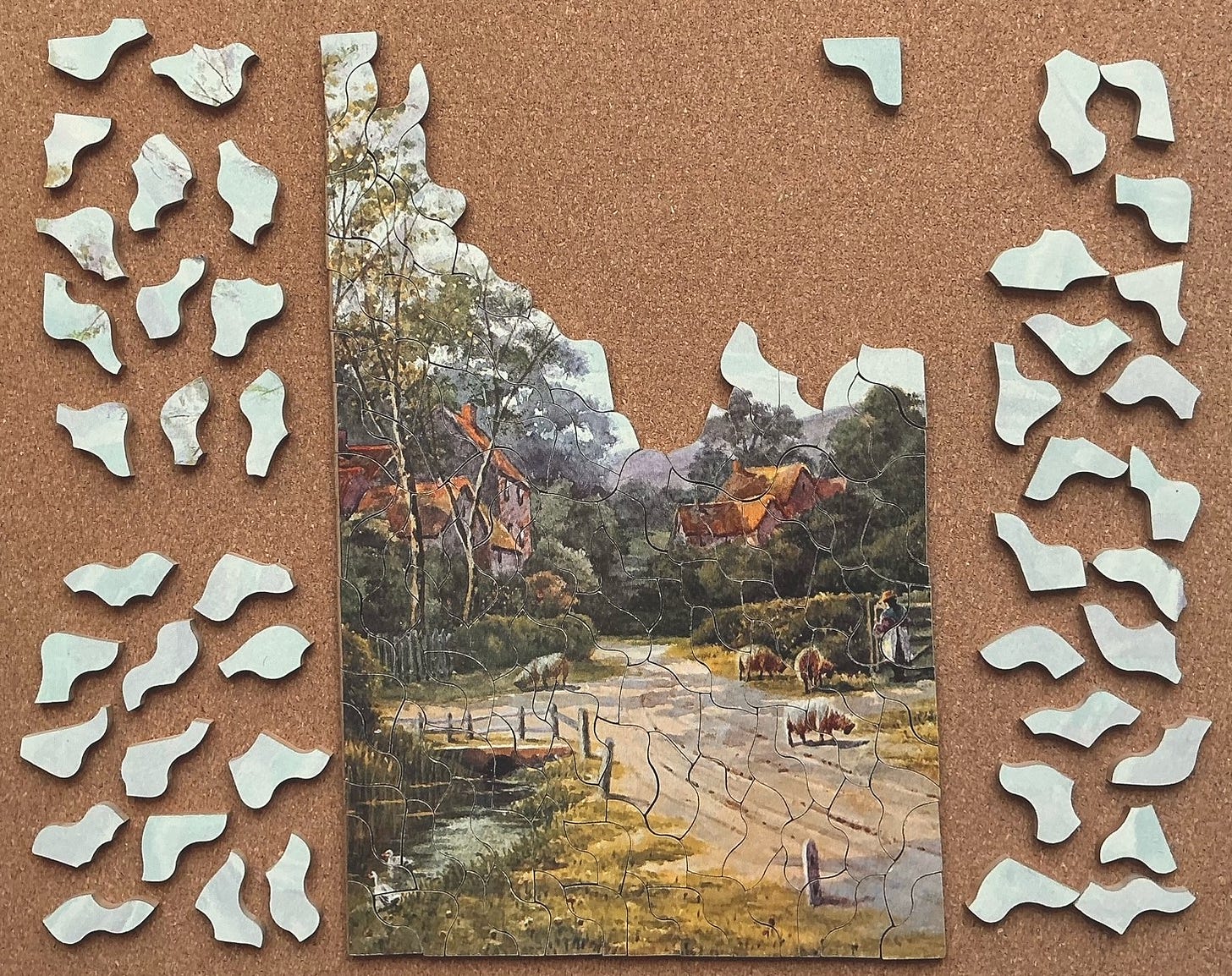

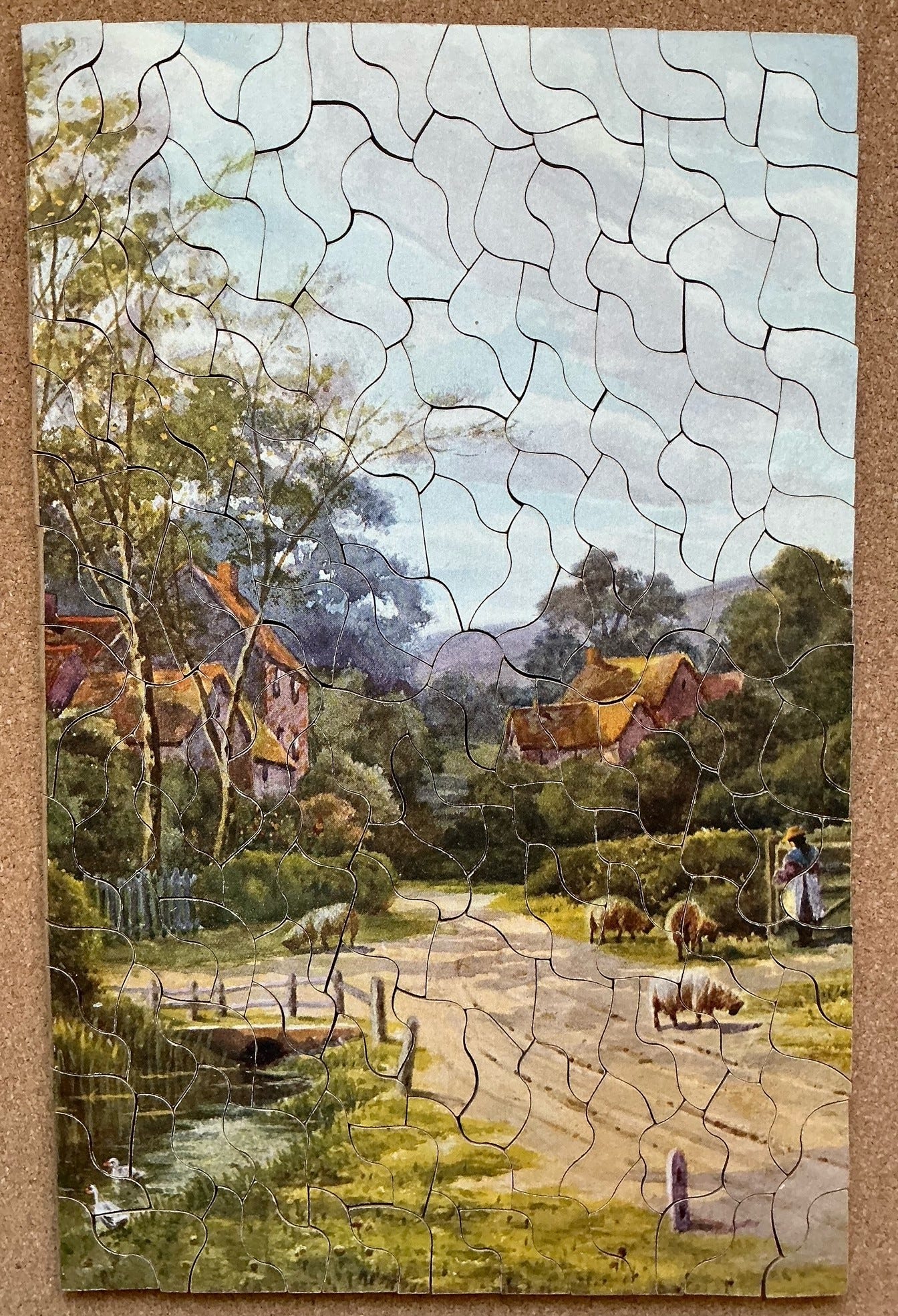

Just for added challenge, in preparing for assembly I decided to sort this 157 piece puzzle differently than usual and to assemble it on one of my small corkboards. I crowded all of the whitish pieces together along the top planning to save them for last, put the green woodsy ones on the left and khaki-tan ones on the right, and spread out the other pieces in between. I thought that I might be able to begin by building a focus of attention for the image with that latter group of pieces.

Given that this puzzle is named A Sussex Village I was surprised that there did not seem to be pieces that looked architectural. Then I remembered that when I bought it I had thought that the picture looked more rural than village-like. But that is about all that I recalled about this image: My amazing puzzling superpower of forgetfulness aided me again!

Assembly began with scatter-shot targets of opportunity. I had not planned to begin with the edges but the puzzle led me in that direction. The biggest opportunity came from the fact that, as in An Interesting Story, there is a thin strip down one side of the puzzle where the wood had been slightly larger than the art print. The strip of exposed wood was only about 1 mm wide but that was enough to let me know which potential edge pieces belong on that side, and two ducks in the bottom corner told me that it was the left side. My second largest early subassembly also turned out to be mainly edge pieces.

It was the sheep, and then the tan/khaki pieces that I was able to develop next:

Then the pale green led me westward with quite speedy progress, and to the discovery that I had put in a misplaced piece next to the ducks:

I reorganized the loose pieces and subassembly islands on my puzzle-board and turned my attention to the left side. The Sussex village finally appeared:

The right location for two of those subassemblies had been staring me in the face. This next photo is only two placements after the previous one. Making rapid progress like that is very satisfying! But the fact that I had missed them before taking the previous photo is also a bit embarrassing.

The rapidly diminishing number of pieces that have colour continued with the very quick progress but I knew that would change when all that are left were sky pieces.

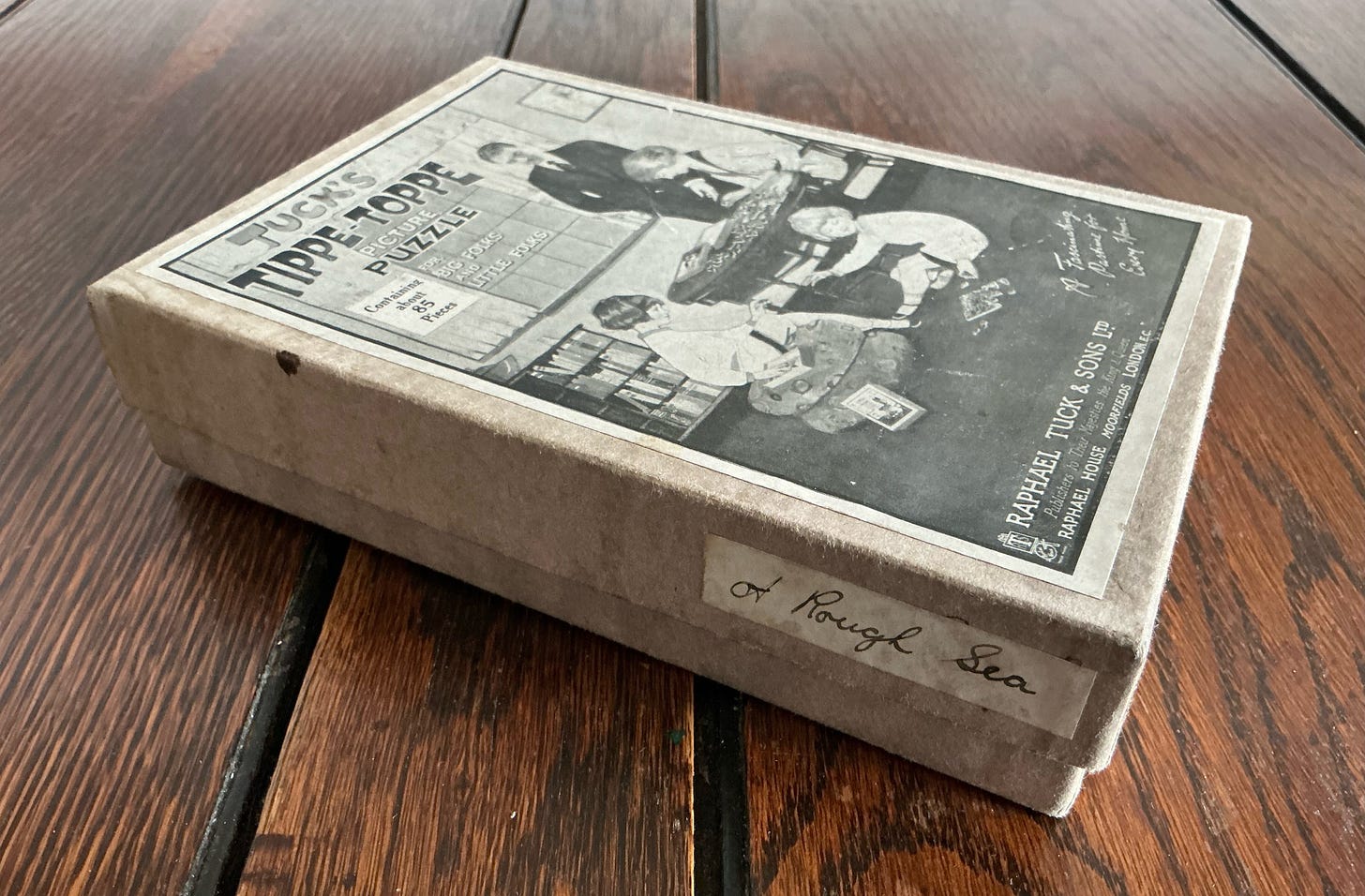

A Rough Sea, made by Raphael Tuck & Sons

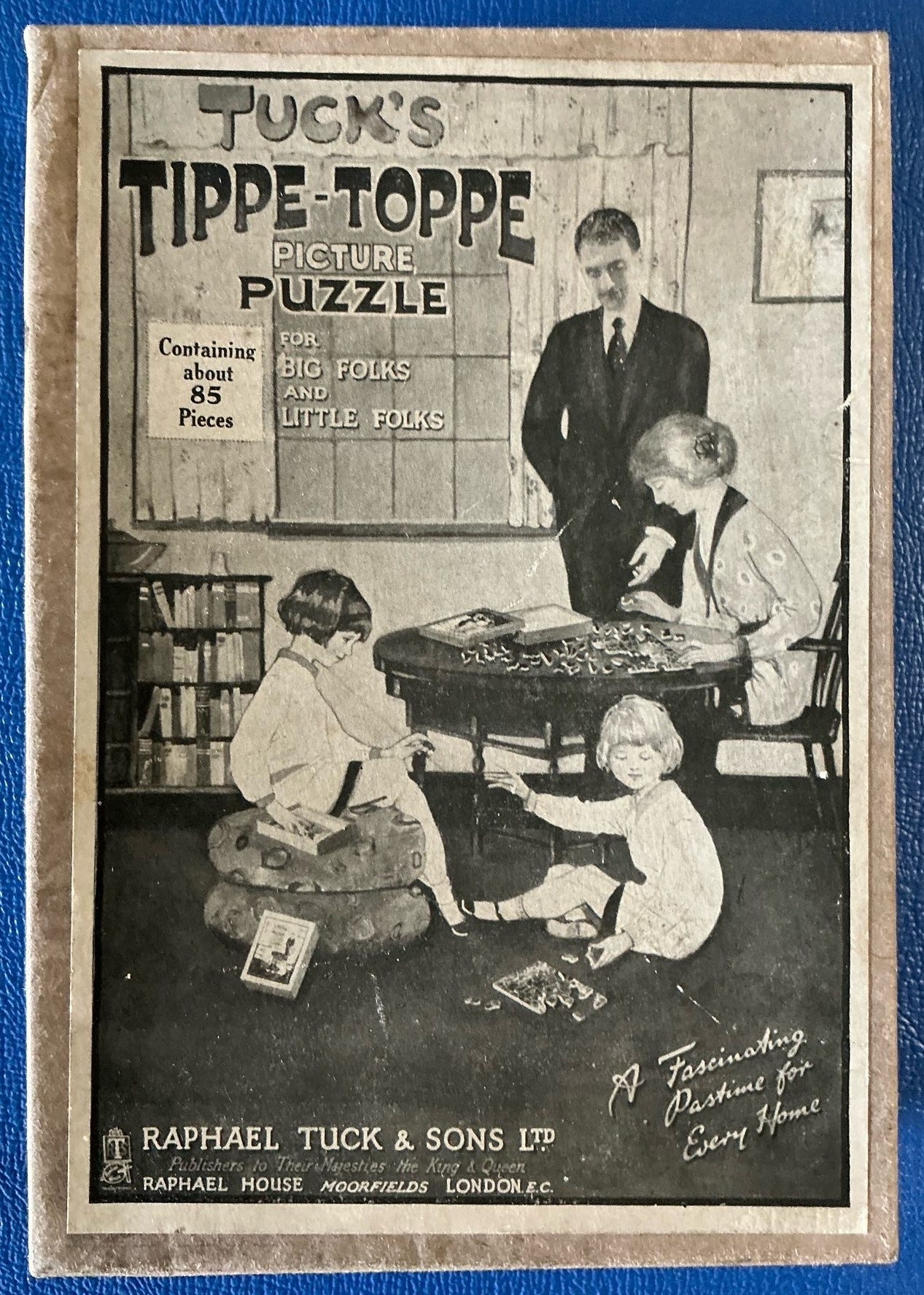

maker – Raphael Tuck & Sons – Tippe Toppe product range London, England

date – 1920s-’30s push-fit cutting

85 pieces (count) 8¼” x 11” (21x28cm) 6.9 cm²/pc 3.5mm 3ply

artist – possibly William Joy (1803-1865)

This is another small push-fit puzzle, but this one is not as high end and is probably from a few years later. It was made by the Raphael Tuck & Sons company. Tuck was actually quite a renowned firm (with a Royal Warrant no less!) and was the major puzzle producer during the first jigsaw puzzle craze and the Great War that followed it soon after. It was still a respectable brand during the second jigsaw craze in the early 1930s but its market share withered because its offerings failed to keep up with modern tastes when faced with intense competition from G.J. Hayter (“Victory” brand), (J. Salmon & Co. (Academy), and Chad Valley, all of whom grew and thrived during those hard times.

Like many makers, Tuck stopped making puzzles and turned to wartime production when WWII began. Actually, printing rather than puzzles had always been what they were primarily known for, and they never even tried to return to making puzzles after the war. You can learn more about the history of the company from my reports about their A Precious Load and The Band of the Life Guards in State Dress puzzles here, and from my write-up about the image of Guildford High Street (here).

This small 85 piece puzzle is from the company’s Tippe Toppe line, which is something of a misnomer - they were a less expensive series of relatively small puzzles aimed for older children and families. That is probably why I was able to buy it for only £10. Raphael Tuck puzzles, even small ones, usually sell for much more than that at auction but collectors of old children’s puzzles are an even smaller market niche than collectors of ones for adults. (The fact that half of the pieces are sky probably also helped.) But I’m glad I bought it because it was another good stepping stone for me into the challenging world of push-fit puzzles.

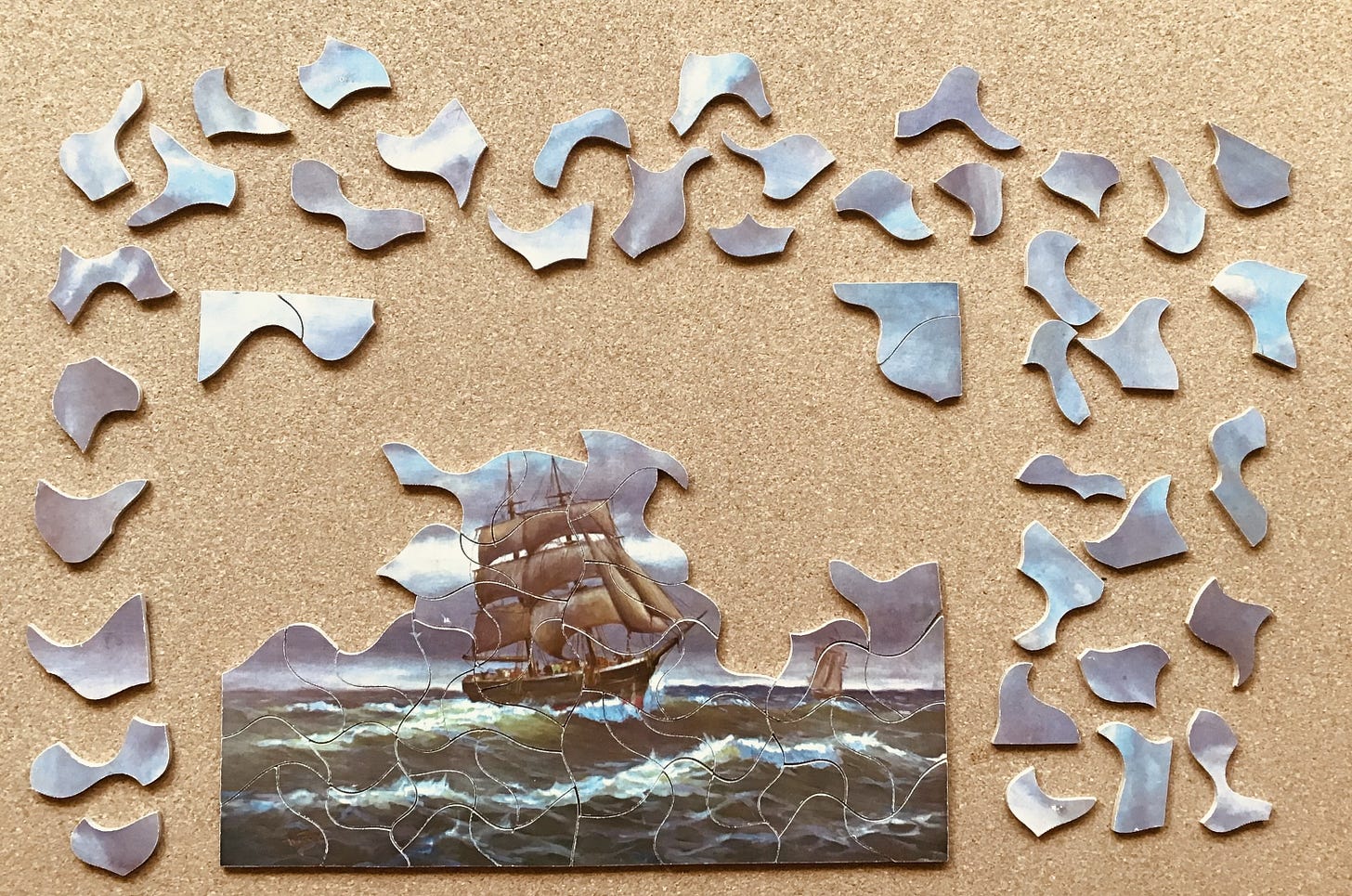

Above is the only in-process photo I took. I should have included a ruler in the photo to show you how large these pieces are. They average almost seven square centimetres each, compared to the 3-4 centimetres that we now expect in most adult jigsaw puzzles. The shape of such languorous cut-lines is called “crescent” in Bob Armstrong’s classification system but technically they are interrupted long-period sinusoidal (sine wave) curves. They dissect the puzzle into interesting lovely-shaped pieces, and are also easy, intuitive and quick to cut. The one thing they don’t do is interlock. Not at all.

As mentioned, Tippe-Toppe was not one of Tuck’s top-of-the-line puzzles. The bottom layer of the 3.5 mm thick 3ply was split but that did not affect assembly. Looking at the puzzle from this side it is easy to see how the cutting of this one proceeded. The cutter started with a blank – a piece of wood cut-to-size to which the paper-printed image had been glued on by someone else. The blank was cut into halves from top to bottom with a gently curving continuous sine wave, then each half was cut from side to side in the same manner. Each of those quarters were quartered again, and finally the remainders were cut into approximately equal sized pieces, always with the same gently curving cut-lines.

After cutting, the pieces would have been passed along to someone else who was responsible for counting them, reassembling them for quality control, and sanding, especially to remove the rough burrs that the sawblade left along the bottom side of the cut-lines. The pieces would then be put in an appropriately-sized box and the handwritten label with the puzzle’s name applied.

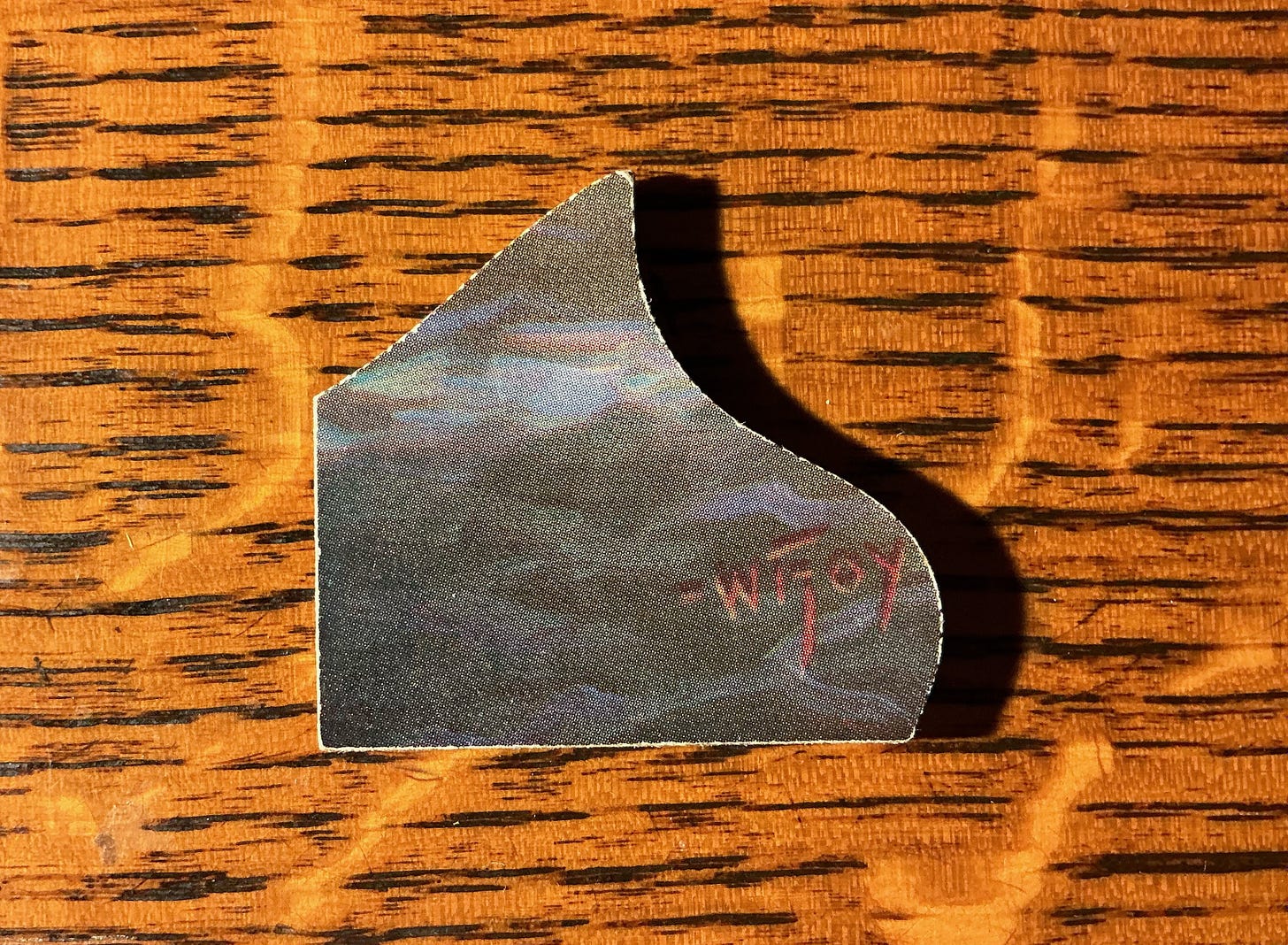

The image on this puzzle has the artist’s signature:

It is hard to decipher but the painting is possibly by the acclaimed 19th century British maritime artist William Joy (1803-1865). The painting certainly seems to be in his style to my eyes. He and his brother John Cantiloe Joy lived and worked together their whole lives, although William is the more highly acclaimed. They had been born in the fishing and shipbuilding village of Southtown, or Little Yarmouth, which was across the Yare River from Great Yarmouth in the English county of Norfolk on the North Sea.

The bothers came from a working-class background and both were expected to become tradesmen, but the author and inventor George William Manby recognized their artistic talents and became their patron and mentor. In 1818, he provided them with a studio and trained them to become skilled maritime artists. By the 1820s their paintings were being displayed by the Royal Society of British Artists, the Royal Academy and at the British Institution. For further information, Wikipedia has a long entry about the brothers.

Both branched out into various other styles but are still mostly known for their maritime paintings. William enjoyed depicting powerful, raging seas and storm-tossed ships, while John’s works were usually less dramatic. I wonder if Tuck selected this image for the puzzle because the Tippe-Toppe box-top says “for big folks and little folks” and this scene would have been less scary than most of William Joy’s other paintings.

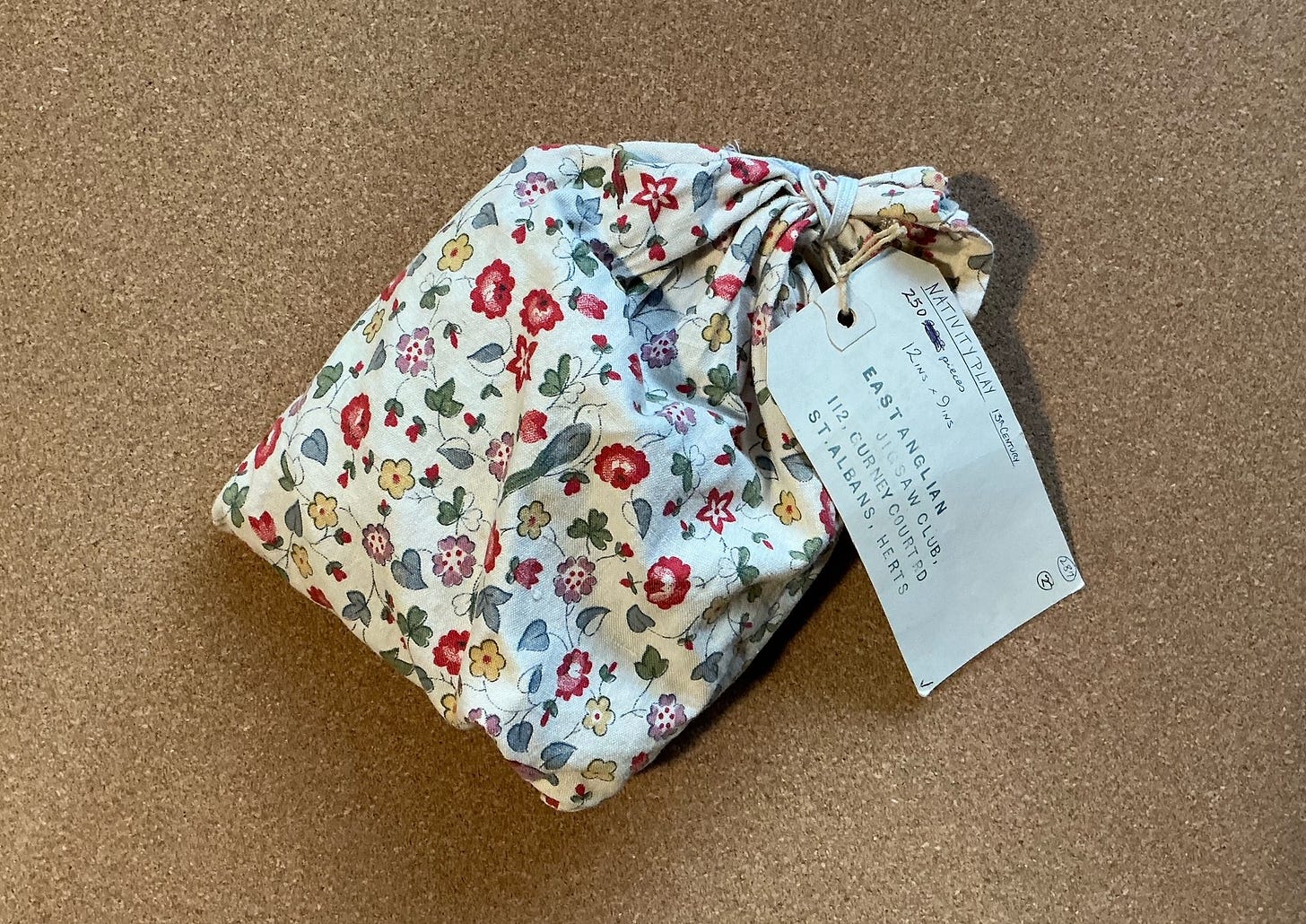

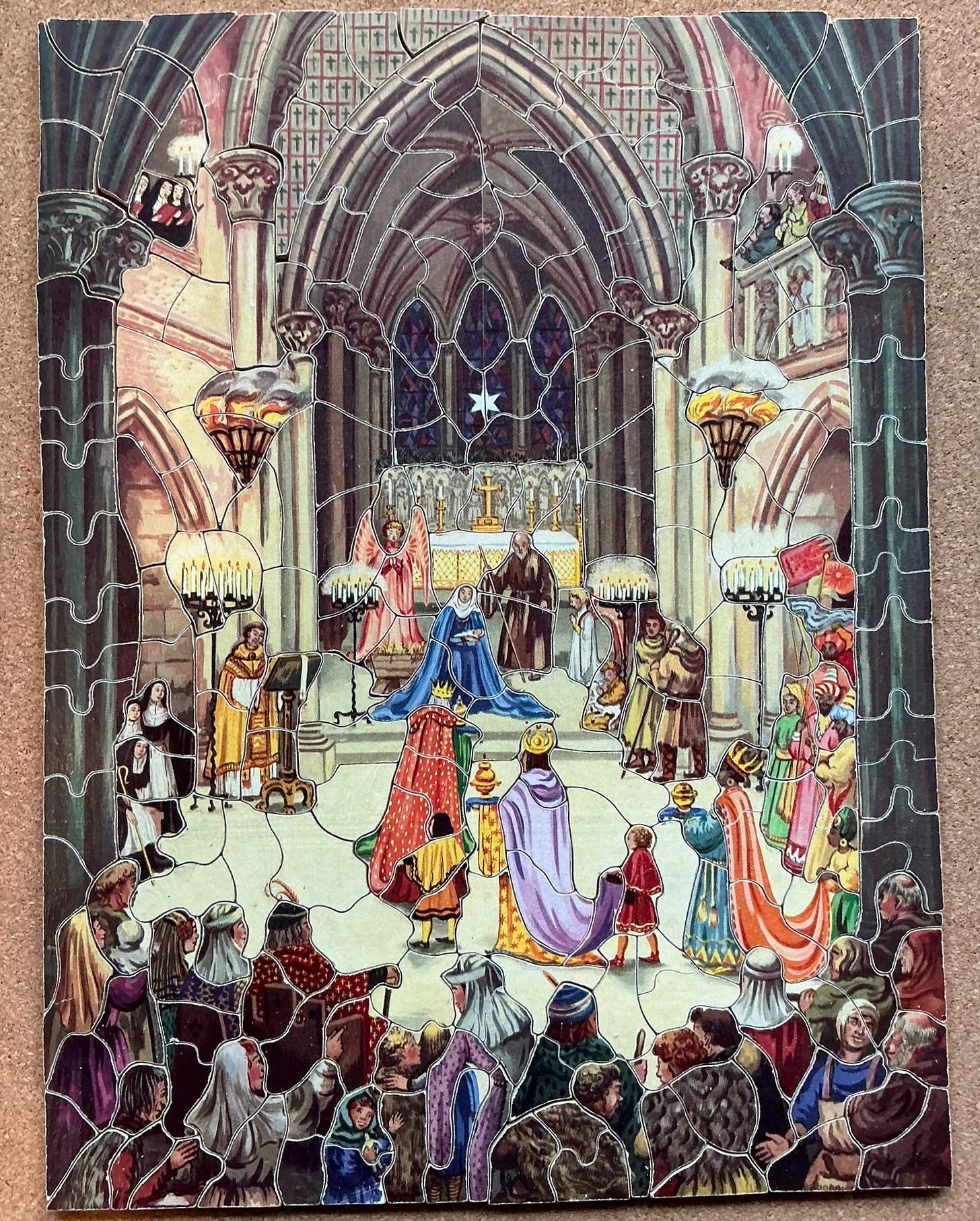

Nativity Play, 13th Century – East Anglian Jigsaw Club

puzzle-maker – unknown (but my guess is Dolly McDougall)

date – unknown (1950s - ‘60s) artist unknown

250 pcs 12” x 9” (30 x 23 cm) about 2.7 cm²/pc 4mm 3ply

entirely colour-line cutting and push fit; no figural pieces

After the Jigsaw Jag subsided the various companies that had established puzzle-making workshops and factories competed for the still-significant demand for jigsaw puzzles. As previously mentioned, one way was by shifting from thin hardwood sheets to the less expensive and more warp-resistant plywood. The craze had not just been in North America and England, but had also erupted in Europe in such countries as France, Germany and the Netherlands, and it was from there that the biggest innovation came to maintain and revive interest in jigsaws – the invention of including interlocking knobs into the cutting designs.

Those interlocking knobs with which we are now so familiar were instantly extremely popular and it wasn’t long before almost all of the manufacturers were making their puzzles that way (and the ones that didn’t adapt did not last for long when even more competition emerged during the second Jigsaw Craze that erupted in the early 1930s.)

But there has always continued to be a few fans of the non-interlocking cutting from those who appreciate the extra challenge and delicate touch that is needed to assemble them, as well as their old school vibe. Often their demand is met by beginning cutters who are first learning how to use a scroll saw, but also by skilled cutters who have wanted to continue making puzzles the old-fashioned way. Among the latter were Rory McDougall, his wife Dolly, and their grandson Andrew Kershaw.

This puzzle is was made for the East Anglian Jigsaw Club puzzle library. British puzzle expert David Shearer, from whom I bought this puzzle, has this to say about that library on his The Jigasaurus website:

[The East Anglian Jigsaw Club] is a lending library set up in the 1950's by Dolly McDougall and which continued to operate until around 1969, the last three years being run by her grandson Andrew Kershaw from Beccles in Suffolk. The library began soon after Dolly's husband, the Rev. Rory McDougall, himself an accomplished cutter of wooden jigsaw puzzles, died in 1951.

Dolly went on to expand the stock of puzzles herself, by learning to cut and became highly skilled and utterly fiendish in some of her own techniques. When Dolly passed away in 1966 her grandson, Andrew Kershaw, took over the library and her fretsaw. He also became an adept cutter and added further to the stock, with his puzzles usually being housed in sturdy boxes, as opposed to the earlier cloth bags. …

My review about a Chad Valley puzzle called of The Royal Route to the West (here) includes a very long digression about puzzle libraries and clubs, which are basically like privately-run book libraries. As Tom Tyler puts it in his book:

Books and jigsaw puzzles had one thing in common – many people want to read or assemble them only once. … Once the puzzle is assembled and the challenge conquered most people lost interest in the puzzle though they may have a few old favourites. Often, however, they liked to be able to exchange the completed puzzle for another and this was the role for the libraries. The library or club would seek to build up a large stock of difficult wooden puzzles … without, as a rule, guide pictures. Members paid a yearly subscription fee plus the cost of postage and, usually, there was no limit for to the number of puzzles a member could borrow during the year.

According to Tom, the East Anglian Jigsaw Club “had about 70 members living as far away as Cornwall, Liverpool and Grimsby.” Puzzle clubs/libraries tended to be established by puzzle cutters. For one thing, that skill was needed to make replacement pieces for ones that have become lost or damaged, but like Dolly and Andrew they also cut new ones for their libraries. That would generate a stream of income after the puzzle was made rather than a one-time infusion of cash, and also make the products of their creativity available to people who would never be able to afford to buy them.

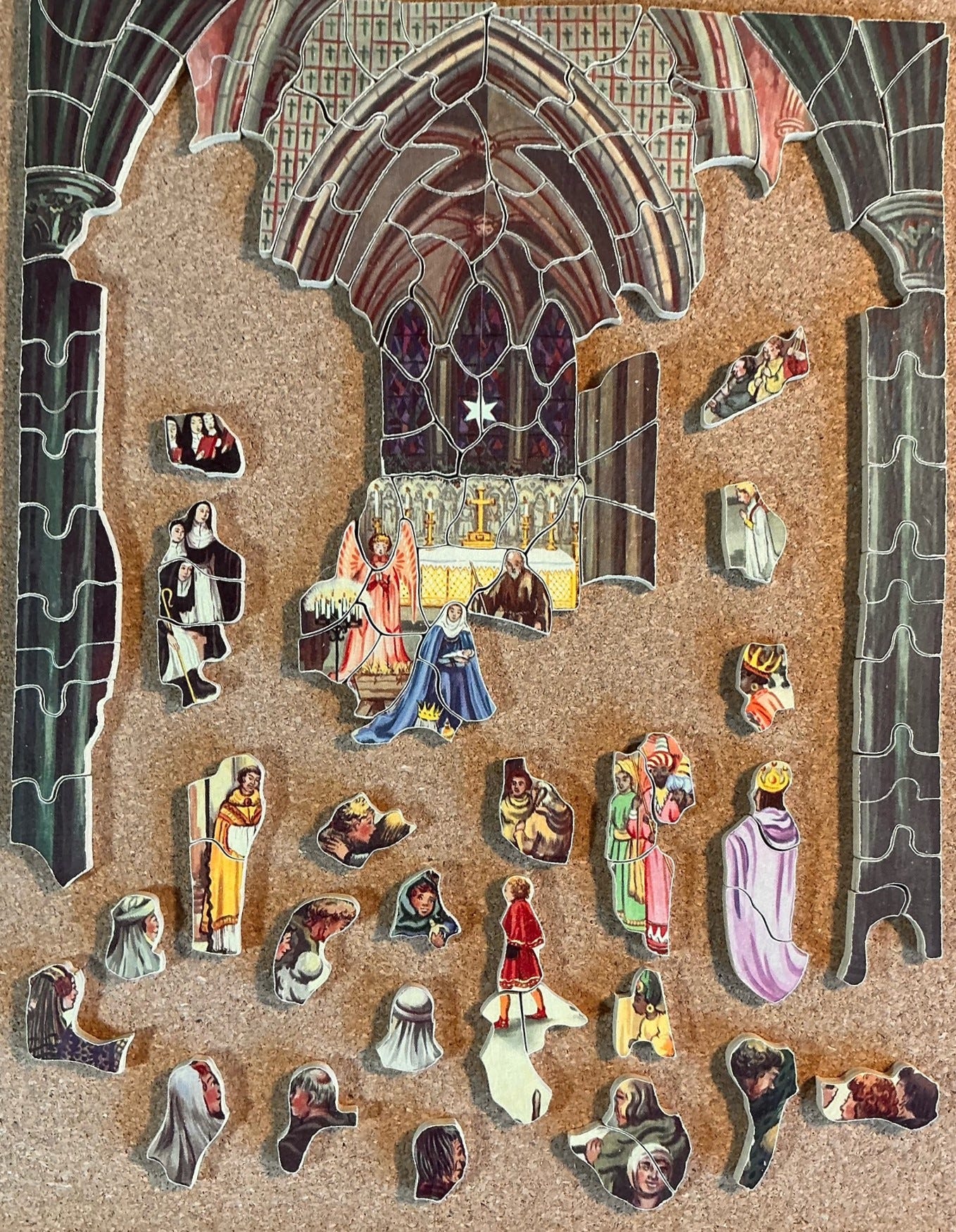

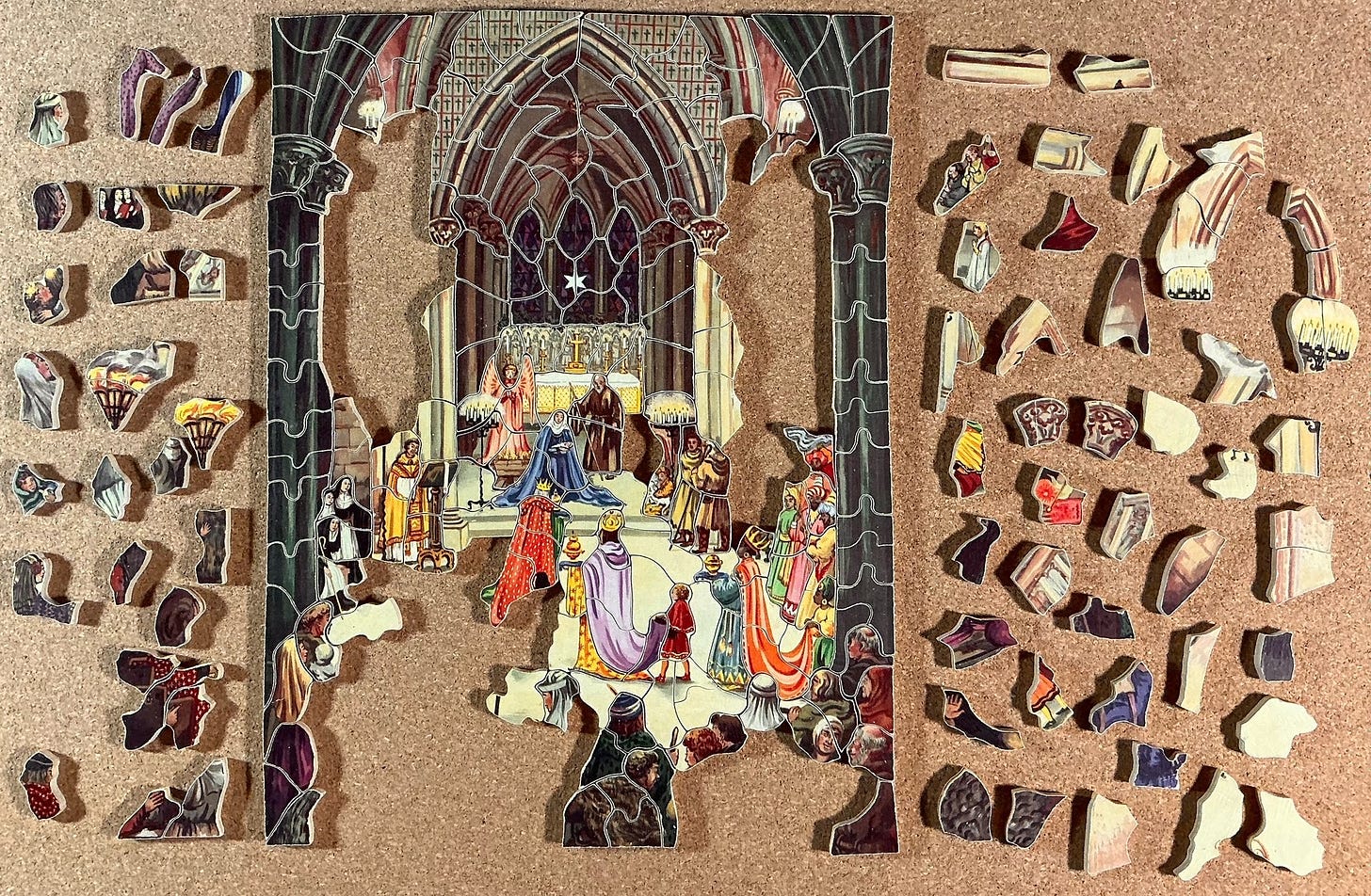

I knew when I began assembly of this puzzle that its 250 pieces would present quite a challenge. My previous experience with push-fit puzzles had only been with small ones (like the previous ones in this report) or ones that were only non-interlocking within a frame of interlocking edge pieces. And besides being push-fit, I remembered from when I had bought it that it would have very extensive colour-line cutting, with which I also had limited experience.

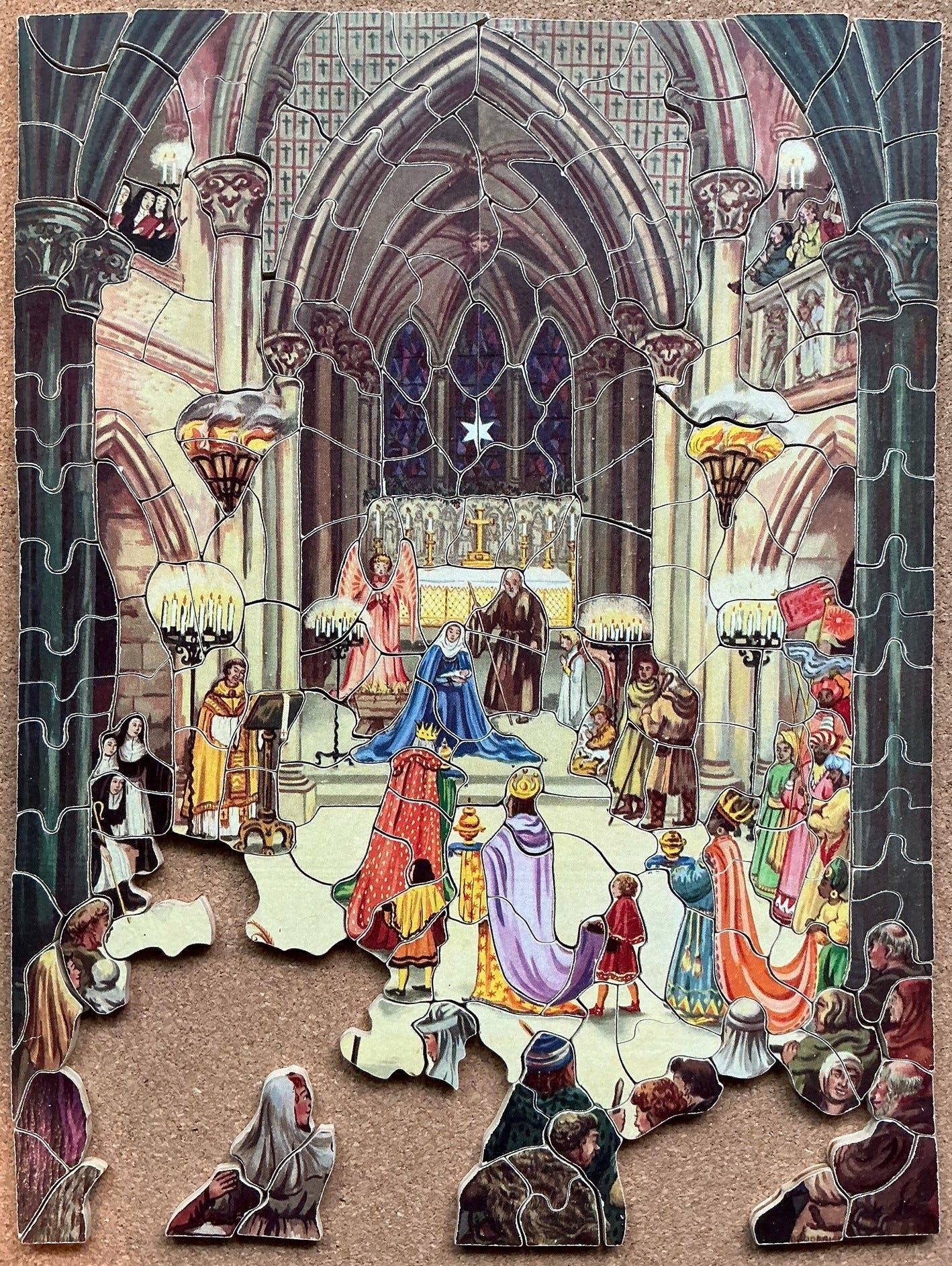

The only other things that I remembered were that the image looked like a Nativity pageant scene inside of what looks like a Gothic cathedral, and that Mary and the baby were central to the composition. I’ll let you discover the image the way I did, although I didn’t think to take as many photos as I should have – I got too engaged in assembly. The first step, as usual, was to do an initial sorting. The pieces are small (averaging well less than 3 cm²) so I had a lot of room on my board to work with.

I had mainly sorted the pieces that looked like people on the bottom centre-left of my board, the other ones that looked like architecture around the sides and top, and the unknown ones in between. That led to two parallel assembly streams – people and architecture.

You might think that I got to the above stage rather quickly but you would be wrong. Even those dark architectural linear runs with protruding (but not interlocking) bulges that obviously were going to be edges were tougher than usual edge assembly. I began to wonder: Was this because my puzzling skills had suddenly deteriorated, or because this cutting is particularly devious? As you can guess, my ego preferred the latter scenario, and subsequent assembly fortunately showed that to be the more likely explanation.

There were times during this assembly when I was tempted to look at the photo that I had printed off from the eBay auction site when I bought it. But I was able to finish it no-peek and was rewarded for that both by a feeling of accomplishment and by enjoyment from having my attention drawn to all of the interesting little details that this image has to offer.

When I had been doing my initial sorting I noticed several ink marks on the back sides of the pieces. Like many home-based jigsaw puzzle cutters of their day, Rafe, Dolly and Andrew all made puzzles from used tea crates so that is probably what the stenciled marks were. But this is what happened when I tried using my usual method to turn the puzzle over:

This is another puzzle that I bought from David Shearer but I did not discover his entry about it on his The Jigasaurus website until after I completed it. I fully concur with his description as it being : “A very challenging little non-interlocking plywood jigsaw puzzle” and that “excellent colour line cutting throughout made this a very enjoyable task of assembly.”

Conclusions regarding push-fit puzzles

The pieces of push-fit puzzles seem determined to dislodge themselves from their neighbours with even the slightest touch of the pieces or bump of the puzzle-board, and moving sub-assemblies to put them into place often involves reassembly for someone like myself who is more-than-a-little-bit clumsy. But while doing these push-fit puzzles I have developed some techniques to lessen the recurring need to realign dislodged pieces. The main one is not to assemble on a slippery surface; another is to brace the heel of my hand on the puzzle-board before trying to very gently slide a new piece into place.

Mind you, I still have to do a lot of repair work but it seems like a reasonable price to pay to enjoy the truly old-fashioned style of this type of vintage puzzle. Their being so out-of-fashion is what makes them distinctive and a nice break from interlocking puzzles, just as many other vintage hand-cut puzzles make a nice break from the ubiquitous whimsies found in laser-cut puzzles. And speaking of “reasonable price”, most puzzle people are not into them at all so with some exceptions they usually sell at auctions for much less than other wooden puzzles of comparable size and condition. In other words, they are an ideal “frugal alternative”.

These have whetted my appetite for more push-fit puzzles but for now at least I think I’ll remain inclined to buy and assemble only relatively small ones.

Dear Bill,

Wow! You must have done a lot of research for today's posting. I'm goint to list, in point form, some of my reactions to your essay:

1. I am one of those people who did not know that knobs of jigsaw puzzles were not especially common before the 1920s.

2. I especially liked the five photos showing the progression of assembly for that oldest of the puzzles in your collection.

3. The treadle scroll saw reminds me of a treadle sewing machine that I saw my mother, aunt, and grandma use during my childhood.

4. Reading what you wrote about the 1907 financial panic in regards to the subsequent jigsaw-puzzle craze that developed seems like an interesting coincidence to me because my wife and I recently finished studying a history course on DVDs which featured details of that particular financial crisis.

5. The boxes pictured in your posting are almost as interesting to see as are the puzzles.

6. "A Rough Sea" is another puzzle today that particularly catches my eye.

7. The further information about whimsy pieces is continuing my education, because I hadn't even thought much about such pieces until you began analyzing wooden puzzles and loaning some of yours to me in recent years!

8. My friend Al is from East Anglia, and I'm going to direct his attention to what you've posted about Tom Tyler and the East Anglian Jigsaw Club. I know that he is aware of your wooden-puzzle blog, but he is also in the midst of renovating an old house, so he may need my reminder to get him to look at today's posting.

9. I don't personally feel patient with push-fit puzzles, though I got pleasure out of reading about them today.

Thanks,

Greg