37. Puzzly Part 2: Research inspired by the artwork

Three puzzles with three very different images led me down three interesting rabbit holes (about 3500 words; 12 photos)

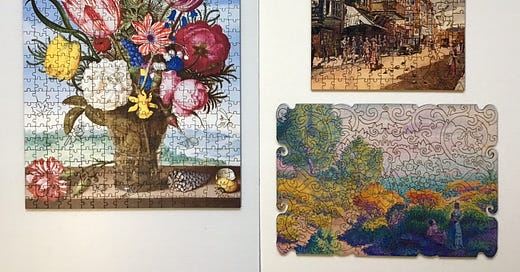

Despite the title of this newsletter, this essay is not about puzzles: It is about the artwork that was used as the images in the three puzzles that I reviewed in my last essay about Britain’s Puzzly Company.

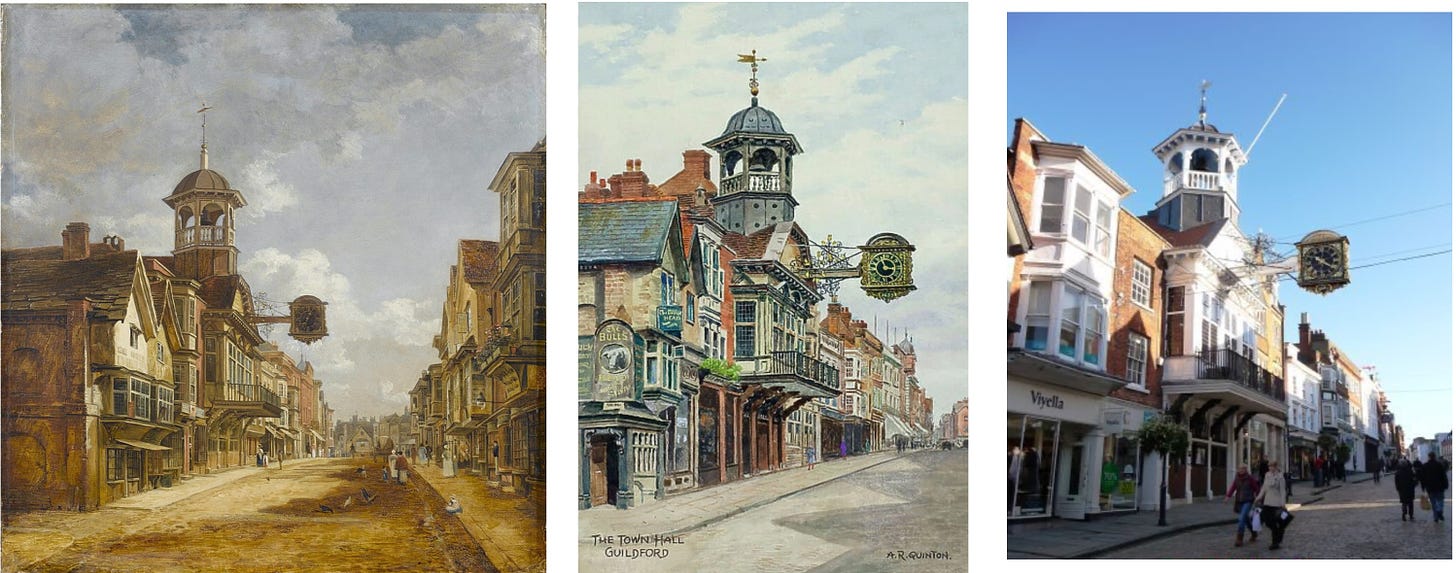

Guildford High Street

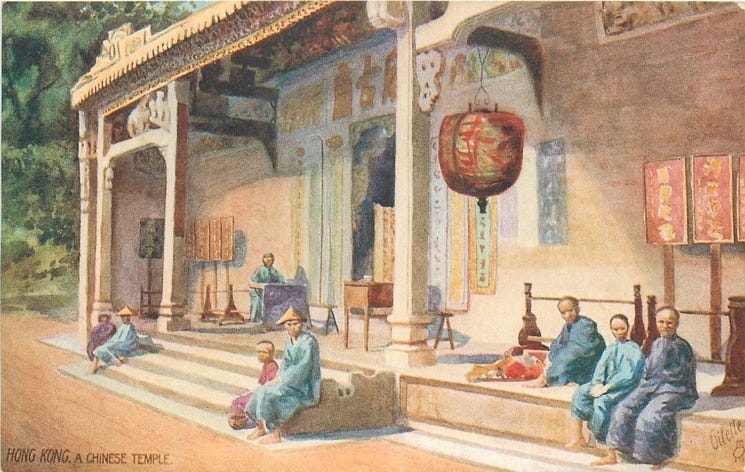

The artwork for this puzzle is a photo of a vintage “Oilette” postcard made by Raphael Tuck & Sons. I tend to think of that company as Britain’s leading jigsaw puzzle manufacturer during the early 20th century (prior to the Great Depression.) But in the late 19th and early 20th centuries they were more famous as a high-quality printing company. Raphael Tuck had started the company in Germany specializing in making art prints, but it really made its reputation when he went international, establishing branches in Paris and London, and branched out into Christmas cards.

Raphael Tuck did not invent printed Christmas cards but he was one of the first printers to sell them ready-made rather than as an item that had to be made to order, and his were the first ones that featured images of the religious aspect of the holiday.

It might be recorded as one of the ironies of history that a Jew, a respected Talmudic scholar, would be remembered as the chief exponent and promoter of the Christmas card. Raphael discovered that Christmas card designs were mainly secular; and in spite of the increased religious consciousness of the Victorian age, these cards featured the gaiety and revelry of the holiday season. In 1871 Tuck supervised the design of Christmas cards featuring the religious aspects of the season: Jesus Christ, the Holy Pair, the Magi, the Nativity scene, as well as the traditional Santa Claus, holly and mistletoe. (source)

The company went on to create new markets by introducing such items as printed birthday cards, Valentines, and other pre-printed greeting cards. Among the famous people at the time who found such greeting cards handy for correspondence was Queen Victoria. She knew that people highly prized receiving correspondence from her, but had far too many friends and acquaintances to be able to write out individual personal greetings at Christmastime and other holidays. In 1883, Raphael Tuck & Sons was granted the Royal Warrant as “Art Publisher to Her Majesty the Queen.” Later British monarchs also granted the company a royal warrant for their printing.

But the Tuck company, under Raphael’s son Adolph, really hit it big as a maker of picture postcards. Again, they did not invent postcards, and in fact they were rather late to get into that field. The history of postcards goes back to the 1860s in Germany. But in the 1890s the company was well-positioned to make high quality ones because technical advancements had made colour printing more economical and better quality. In 1899 the Royal Mail (finally!) followed other countries’ lead and changed its postal regulations to make them less expensive to mail than letters, and they began to allow short messages to be included on the address side of the card. The next year Raphael Tuck & Sons began making picture postcards.

They, of course, weren’t the only printing company that capitalized on this opportunity, and arguably they didn’t even have the best artwork. Compare, for example, the middle image below that depicts exactly the same buildings as the image on my puzzle. It was commissioned for J Salmon Ltd, another postcard printer who also happened to be a wooden puzzle maker. But Raphael Tuck & Sons was the only British postcard maker who had the prestige of a royal warrant (which they displayed on every postcard) and they also had a technical trick up their sleeves.

The main reason that postcards proved to be a big success for Tuck wasn’t only because people were mailing them, although doing so was extremely popular from about 1890 until the Great War and remained popular until the recent decline in “snail-mail.” Early on, people took to buying them as inexpensive souvenirs. In fact, postcards began to be treated by working-class people as an affordable miniature art collection whether they featured fine art or exotic places. For many years postcards were the world’s third most collected item (after stamps and coins.)

That is where “Oilette” postcards come into the picture. In 1903 Raphael Tuck & Sons developed and patented a new technology that made them their new top-of-the-line postcard product. Rather than hand-tinting photographs of exotic places the company commissioned artists and illustrators (often unidentified, as in this one) to adapt images from photographs into paintings. But just as importantly, what makes them “oilettes” is that this line of postcards were given a medium-glossy textured finishing coat using a translucent sealant (similar to current-day Mod Podge) that made them seem more like miniature paintings. That, combined with the royal warrant, made Raphael Tuck & Company’s oilettes the classiest postcards to collect, but still costing only a few pennies each.

The following photos compare a tinted photographic Raphael Tuck postcard to an oilette postcard painted based on that same photo (source):

According to this website:

The president of the Royal Academy, who visited the remotest corners of Scotland each year, expressed his opinion concerning Tuck's influence on art. He said, "Mr. Tuck's graphic productions were likely more effective than all of the art galleries in the world." Tuck postcards decorated drawing rooms in elegant mansions as well as country cottages with their uneven, smoky walls. This art connoisseur observed that the world's art galleries could only reach a few people while Mr. Tuck's postcards went to millions of individuals at every level of society.

The scene in the oilette postcard that was used by Puzzly for the image of this puzzle is of Guildford’s Town Hall on its High Street. It was built as a guildhall in the 1550s, and was restored and the iconic clock installed in 1683. As you can see in the above relatively recent photo, that streetscape remains largely the same today.

The cars and the fashions help to date the image on the postcard. Based on the cars I was able to narrow it down to between about 1905 and the beginning of WWI. My friend Beth Skala who frequently needs to date old photos as part of her genealogical research was able to narrow that down further. According to her:

Women’s fashions in 1900 to 1909 had trains and were fuller than in the puzzle picture. Silhouettes thinned down between 1910 and 1914 and hemlines raised to the ankles. I would date this puzzle picture as between 1910 and 1914, just before WWI. The ladies are certainly showing a lot of ankle.

Flowers in a Vase

This is another example in which the picture on the 51cm x 36cm (20” x 14”) puzzle is larger than the original painting. In this case it was an oil-on-copper painting that measures only 28 cm x 23cm (11” x 9”). As you can see, despite being enlarged to nearly triple its original size the image is very sharp and the colours are rich and vibrant with considerable variety of shades and tones. (Assembling this puzzle was a real treat after the darkness of Guildford High Street and it clearly demonstrates the high quality of Puzzly’s printing.)

I had not chosen this puzzle because of a fondness for still-life paintings. I liked the colours and thought that the way they were distributed would make this a good image for a 500 piece puzzle. Being over 400 years old this is the oldest image on a puzzle that I have assembled to date, and I like the fact that it is a painting genre that was once extremely popular but is now quite out of fashion. I also thought that since I knew absolutely nothing about 17th century Dutch floral genre paintings it would make a good learning opportunity for the research that my ignorance would inevitably spark.

The painting is called Bouquet of Flowers on a Ledge and is by Dutch artist Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1573-1621). It was painted in 1619 during the final but very productive years of that artist’s life, during the early years of what is now often called the Golden Age of Dutch Art.

This was painted during a time when Dutch exploration and prosperity introduced many exotic flowers to Europe from around the world, which became highly treasured collectables in the Netherlands. It is not a bouquet picked from the road-side or from the artists own garden. The varieties of flowers it depicts were very expensive rarities at that time suggesting that this may have been a commissioned “group portrait” of the private horticultural collection of a wealthy client Alternatively, it might be a “best of the best” painting of exceptional specimens that Bosschaert had been able to sketch from life in various gardens where he had visited.

In 1619 when this was painted the Netherlands was near the end of a 12 year truce in an 80 year war to free itself from control by Spain. But despite that multigenerational conflict Holland was still an incredibly prosperous country. The Dutch East India Company had been established in 1602 and its monopoly on trade with the Orient was making Dutch merchants and investors among the most wealthy in all of Europe. This explosion in international commerce brought enormous fortune and power to the Dutch merchants, and unlike other European countries that were controlled by hereditary landed nobility the Netherlands came to be ruled by an urban merchant oligarchy. Among the Dutch nouveau riche’s most fervent passions at that time were collecting and displaying rare exotic flowers in their gardens and realistic paintings of Nature in their homes.

The year 1619 was 18 years before the crash of the famous tulip mania speculative investment bubble which has gained some fame in recent years due to perceived parallels with the crash in the values of “dot-com” stocks at the turn of the millennium and speculative cryptocurrency investments more recently. (For a different perspective on that era’s tulip fever read this article.) But the spectacular rise in the value of tulip bulbs had already begun. Individual bulbs of some two-toned hybrid varieties like the ones shown in this painting would eventually be worth as much as a mansion in the most fashionable neighbourhood of Amsterdam.

Bouquet of Flowers on a Ledge is now owned and on display at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) where it is part of the most significant collection of Dutch 17th century paintings in North America. Most of them were gifted to LACMA by Edward and Hannah Carter, who had been instrumental in establishing that institution. Edward William Carter was a businessman who had founded the Broadway Stores group, which had prospered by being an early adopter in the post-WWII movement of running chain stores in suburban shopping malls. Dutch “Golden Age” paintings had been collected by them from 1956 to 1985.

According to a 1981 catalog of LACMA’s Carter Collection called A Mirror of Nature this painting is one of the highlights of their collection. Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder was one of the first Dutch artists to specialize in floral paintings, and played an important role in establishing Utrecht as the Netherland’s centre for that genre. It is not clear who may have influenced his personal painting style or his selection of floral still-lifes as his specialty. He was probably familiar with the works by Jan Brueghel but he never studied under that Flemish master. But in the end he was highly influential in making this type of still-life bouquet a very popular subject for Dutch art at that time.

Actually, rather than think of this image as a bouquet it might be more accurate to think of it as a group portrait of individual flowers, rendered with the kind of precision that one associates with scientific illustration. Each flower in the painting is as accurate of a depiction as the artist could make of a particular flower painted at what would be considered its peak of perfection. This would especially apply to the two hybrid striped tulips and the yellow bearded iris that are given pride of place in this composition. Dutch art at that time was obsessed with realism but like most of the floral still-life paintings at that time this is not a snapshot in time: This is a fantasy bouquet that depicts flowers that bloom during different times from Spring through Autumn.

This was long before the 18th and 19th century conventions for “the language of flowers” which associated particular standardized meanings with different species of flowers and their colours. But in the 17th century flowers in general already had a symbolic meaning for artists – they were included in paintings as vanitas: protestant reminders of life’s transient nature, the futility of pleasure, and the certainty of death. Unlike many artists, Bosschaert did not rub his client’s noses in such a depressing morality lesson and his flowers show few explicit signs of being vanitas. There are no wilted flowers marring this floral perfection.

But to qualify as “fine art” reminders of transience had to be there, so this painting has dew drops on the leaves on the lower left, and a notoriously short-lived dragonfly on the yellow bearded iris. Even the most explicit reminder of death in the painting is quite subtle: The tiny bug on the white rose (lower left) is a doodgraver, or burying beetle, which digs holes under the dead bodies of mice and other small animals to make nests for its larvae.

The LACMA catalog, written by John Walsh, Jr. and Cynthia P Schneider, notes that one of the most important features of this painting is that the bouquet is not on an indoor table or in a niche like almost all of the other floral still-life paintings of that time period. It is placed on a window ledge, backed by a partly cloudy blue sky. The brightly lit softly-rendered background highlights the minute detail of Bosschaert’s brushwork, and lets the subject matter take on a “brilliance and clarity of color and light unrivaled by his contemporaries.”

It is possible that Bosschaert intended this setting to reference the totality of Nature by placing his impossibly perfect bouquet in the context of nature as a whole, a conception first set out by Petrarch. But . . . :

. . . while Bosschaert mav have known this tradition, it does not entirely explain the relationship of flowers to the extensive landscape with buildings and proud towers, which may have a further moral: that as beauty and decay can be observed in flowers, they can also be found as well in the world beyond.

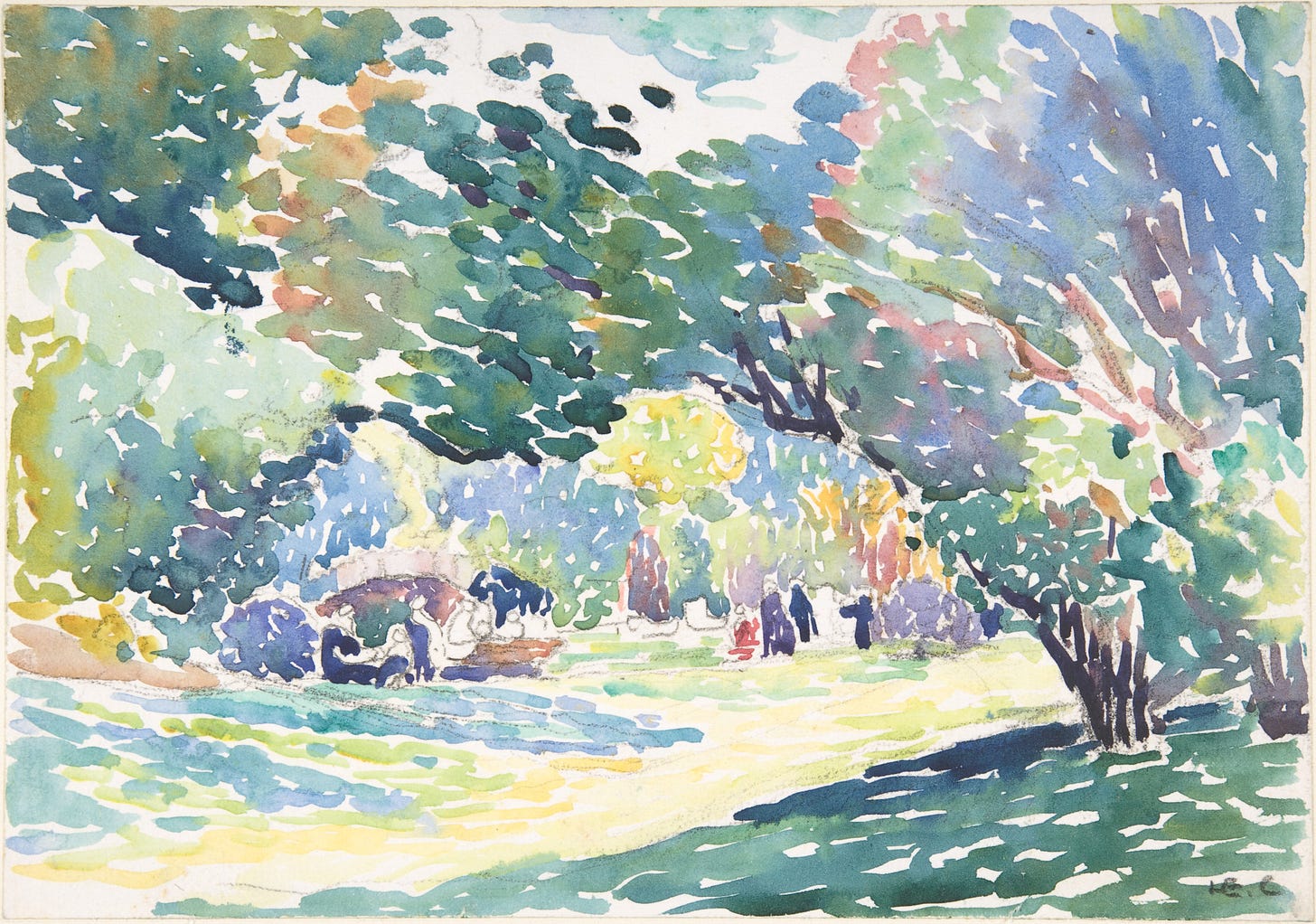

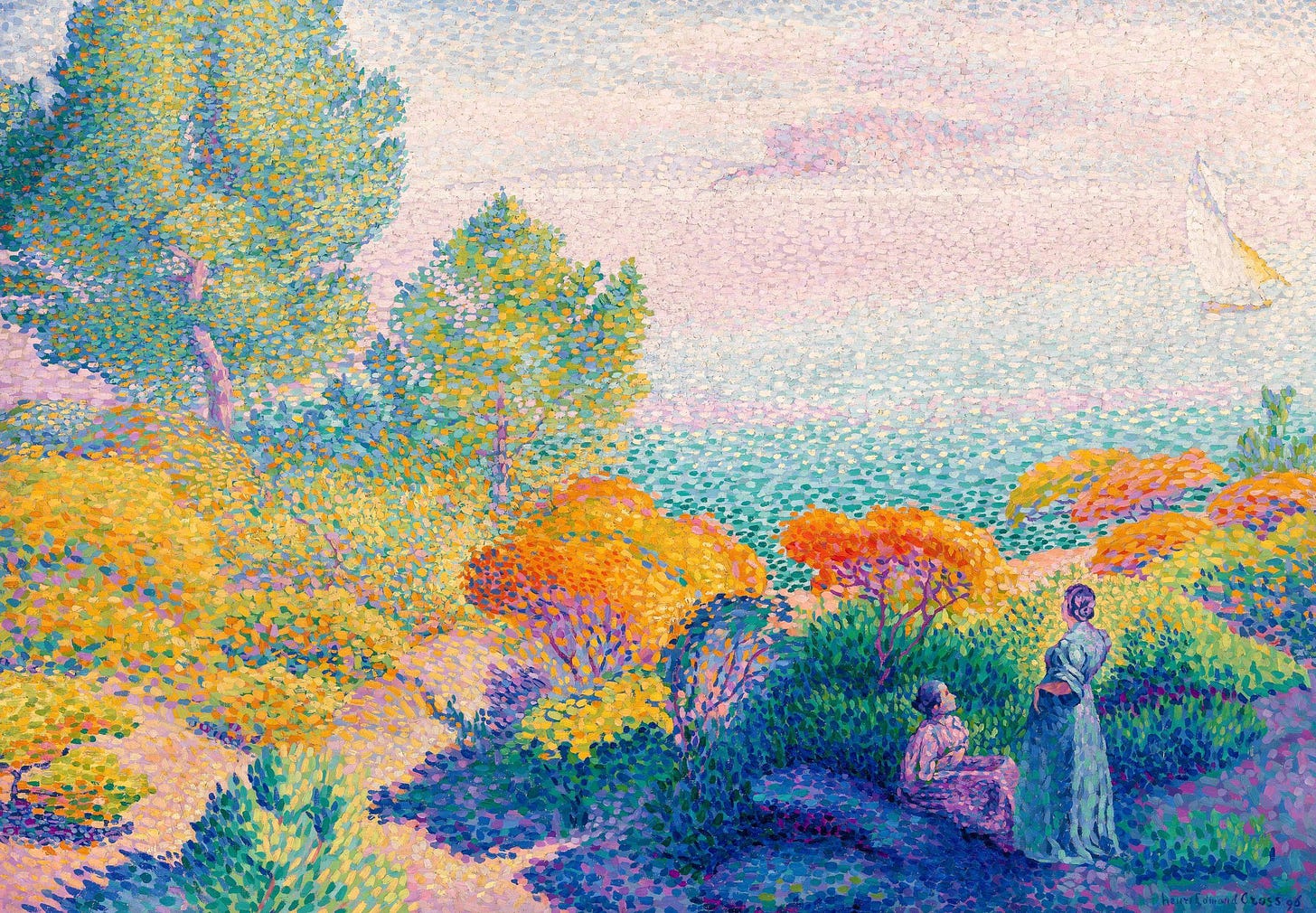

Mediterranean Summer

This is the image on the puzzle that Amelda sent to me for free and it turned out to be my favourite one, both as a puzzle and as an image. As an image side that may perhaps be because I am back to my more familiar artistic comfort zone of impressionism and post-impressionism. I had considered buying it but had trepidations, worrying that the lack of clear lines would make puzzle assembly too difficult. That turned out not to be the case and in retrospect I wish that I had bought it in its larger 36cm x 51cm size (14” x 20; 420 pieces) puzzle size rather than this 200 piece one that is half its size. That would have given me both twice as large of an image to enjoy, and also the larger piece-count would probably have given me more than four times the amount of time to enjoy its image unfolding before my eyes.

The artwork is an 1896 painting by the French artist Henri-Edmond Cross (1856-1910) and is known as Two Women by the Shore, Mediterranean. Its artistic style is pointillism, also known as neo-impressionism, divisionism or scientific impressionism, and Cross was one of that artistic movement’s foremost practitioners.

According to this website:

… Henri-Edmond Cross produced an array of work in the final two decades of his life that played a pivotal role in the development of early twentieth century modernist painting. Initially drawn to naturalism and then Impressionism, he eventually adopted the Pointillist technique pioneered by his friend Georges Seurat, the leader of the Neo-Impressionists. However, the strict precepts of Pointillism did not appeal to Cross's predisposition for individual expression and, alongside Paul Signac, he began to develop a Neo-Impressionist technique that was more intensely colorful and varied in its application. The abstracted forms and dazzling colors that the artist displays in these paintings promptly paved the way for Fauvism.

[Note regarding capitalisation: There is no consensus among art critics and historians as to whether or not the names of artistic movements should be capitalized: In fact, it is a subject of serious philosophical debate in artistic circles. I am trying to standardize my own usage as non-capitalising their names, but to respect that some scholars have strong feelings about this topic I retain capitalization if it is in a quotation.]

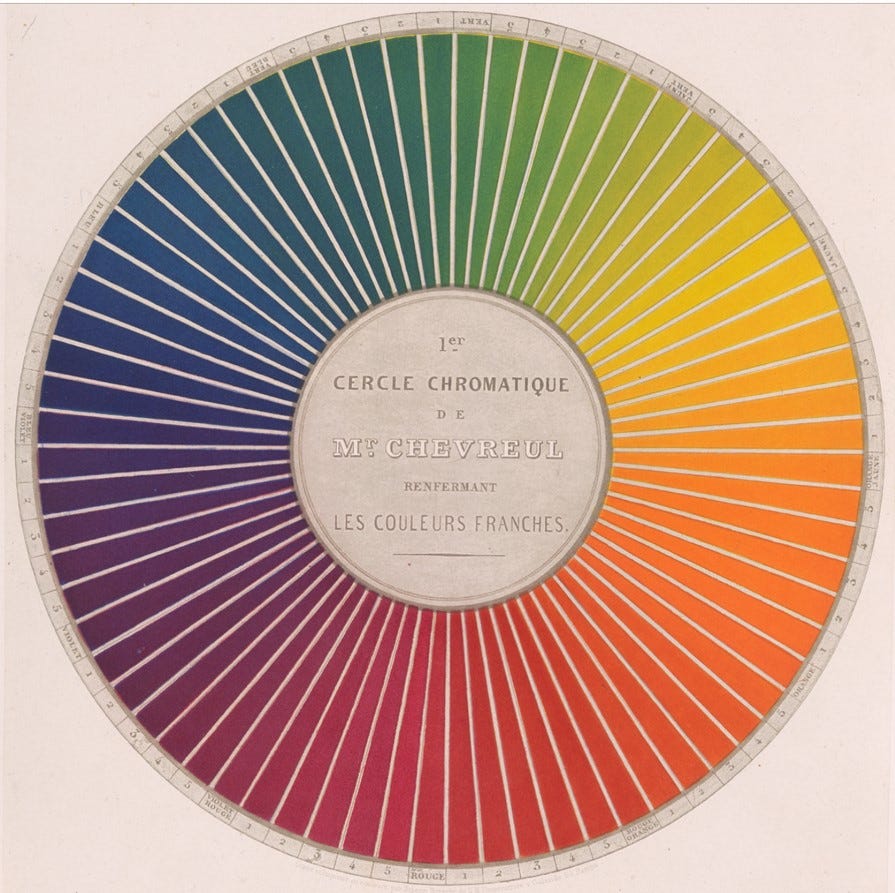

Unlike impressionism which began a very widespread and long-lived revolution in the art world, pointillism was always a small movement almost exclusively comprised of French artists, and only fashionable for about 20 years. In effect, it replaced conventional oil painting’s approach of creating the desired colours by blending paint on the palette with the technique of putting small dabs of unmixed colours onto the canvas, thus leaving it to the viewer’s eyes to blend adjoining colours together.

As with the classically trained realist/academic artists and most of the impressionists, pointillist artists’ colours were carefully chosen based on the latest advances in optics and colour science and theory. Based on the work of such colour theorists as chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul and librarian Charles Henry dabs of complementary (opposite) colours were often placed adjacent to each other to intensify the final effect causing the correctly-chosen colours and shades to vibrate with energy and emotion. But for this effect to work the painting must be viewed from a distance, sufficient for the colours to blend, not examined close up (as one does when assembling a puzzle.)

Painting with little dabs is very meticulous and analytical. It was done in a studio based on impressionist-style field sketches that recorded the fleeting lighting effects and composition that the artist wanted to capture. That is unlike impressionism, where the finished paintings of outdoor scenes were usually done out in nature (en plain air) spontaneously and rapidly.

The pointillist technique was first introduced by Georges Seurat in the mid-1880s and by Paul Signac was one of his early followers. All of the impressionists, including the pointillists, aimed to capture moments in time. The impressionists preferred to paint spontaneously and quickly, directly recording their immediate responses to their subjects. But the pointillist process was very slow, methodical, and based on colour science rather than on spontaneous impressions. When well done the process gives paintings an unparalleled sense of vibrancy. And by leaving glimpses of the primed white canvas showing between the dots the paintings have more light and brightness, it arguably better captures of what natural landscapes look like on a bright sunny day.

Despite these very significant difference in their techniques the pointillists did not see themselves as breaking away from impressionism. They thought of themselves as a refinement or advancement within that movement. In fact, some of the first pointillist paintings were displayed at the last Impressionist Exhibition in 1886. Hence the name neo-impressionism (although its founder Seurat himself favoured the name divisionism.) But pointillism is the name that has stuck. Ironically, as with the name impressionism itself, the name was first used by an art critic to indicate his undisguised disdain for the new format of painting.

Actually, although Cross was a long-time friend of both Seurat and Signac, and had co-founded a new artist co-operative with them to host modern art exhibitions after the impressionist circle had run its course in 1886, he did not adopt this style of painting immediately. In fact, he did not start painting this way until 1891, the same year that Georges Seurat tragically died at 31 years of age. It was as if there had been a passing of the torch, and Cross soon eclipsed the early-adopter Signac in bringing advancements to this style of painting. For example, Cross began using small ovals and rectangles rather than round dots to give the paintings more texture (as in this painting.) Other pointillists including Signac quickly adopted this new technique which came to be called second wave pointillism.

Thanks for this great essay, Bill. I'd have liked it in any case, but it also pleases me because it is quite different from your usual postings, in that this one goes into extra detail about the art work you've found being used by puzzle- and print-makers. I particularly like your comments about pointillism. Also, the picture featuring flowers was my favourite from your previous posting, anyway, but now I know more about it. You are absolutely right that there is great variety and nuance in the varied colours of the work, more variety than I consider usual when presented as a jigsaw puzzle. Thanks again. —Greg