20. December binge of small vintage puzzles

Short reports on eight hand-cut puzzles from three wood puzzle manufacturers (about 4000 words; 40 photos)

Throughout December I was preoccupied with my big pre-Christmas music project, completing the write-up of my 2-part review of the new Victory company’s puzzles, and by other distractions including the World Cup soccer tournament. But I found that I didn’t like not having a jigsaw puzzle going for the occasional break, so I decided to do a December binge of small vintage puzzles for which I did not plan to write detailed reviews or even take in-process assembly pictures

These mini-essays are in the order in which I assembled the puzzles.

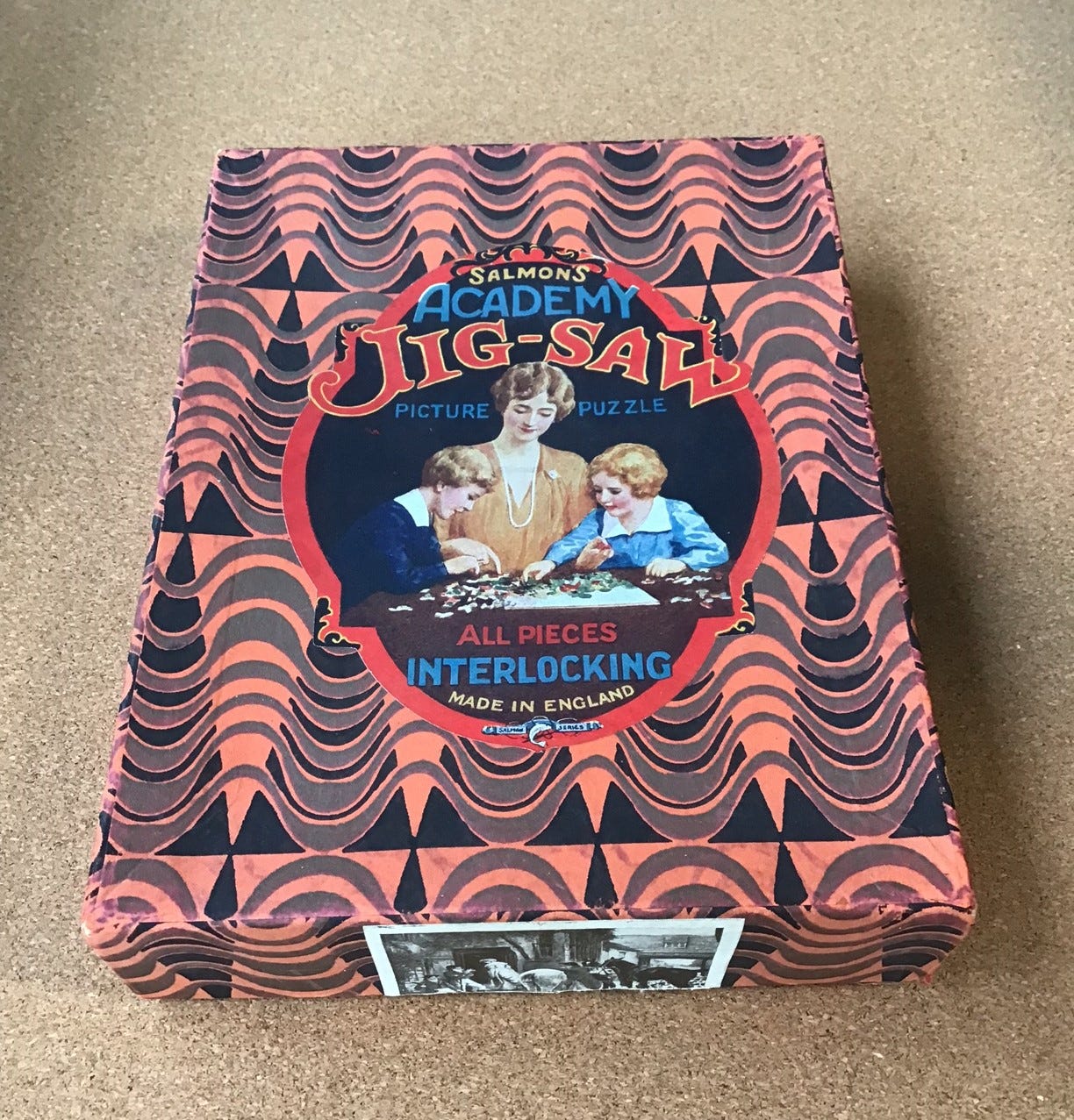

Before the Hunt

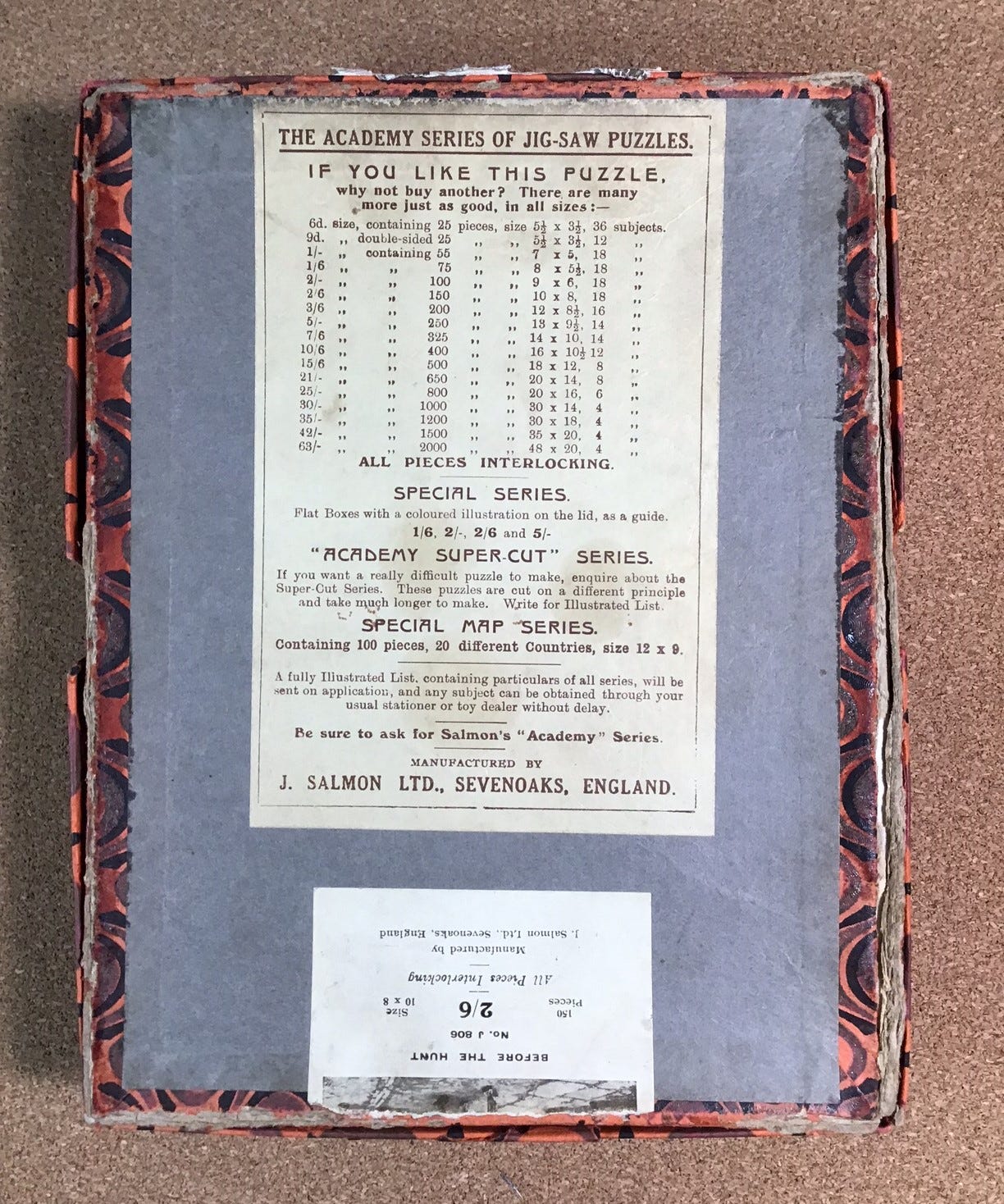

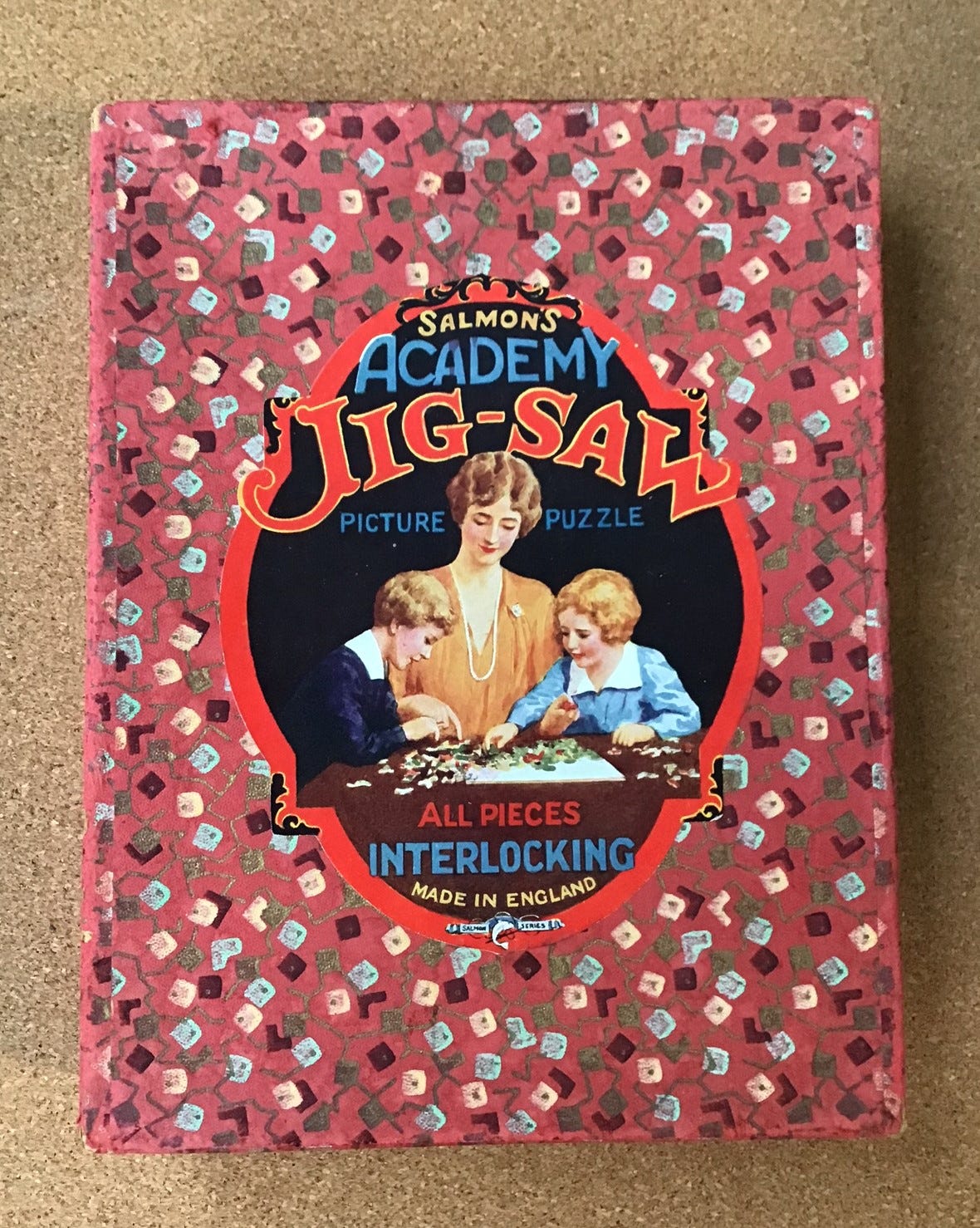

Maker – J. Salmon & Co. Academy brand Sevenoaks, Kent, England

Vintage – 1933

165 pc (count) 8”x 10” (3.1 cm²/pc) 5mm 3ply

I previously reported on two puzzles made by J. Salmon & Company here, and there will be three more puzzles from the same company in this posting. A feature of Salmon’s Academy puzzles that I particularly appreciate is their cutting pattern. Although there are no figural pieces, the constantly-curving cutting gives every piece a rather interesting baroque shape that quite appeals to me. In fact, I think that I prefer the factory-made vintage puzzles when they don’t have whimsies, because their figural pieces were often pretty crude back then.

J. Salmon & Co. was founded as a fine art company in 1880, based in Sevenoaks, Kent, in England. In 1920 it branched out into jigsaw puzzles which they branded as Academy Jig-Saw Picture Puzzles. They employed up to 30 cutters who worked on cast iron treadle scroll saws. During the 1930s Great Depression, which ironically was also the Golden Age for jigsaw puzzles, they competed in Britain in the same price-range and catered to the same general tastes as the Chad Valley toy company, G.J. Hayter’s Victory brand puzzles, and Raphael Tuck & Sons.

J. Salmon & Company received a Royal Warrant as “Toymakers to H.M. The Queen” in 1938. That timing was unfortunate because, like most jigsaw puzzle makers in England, the following year they were forced to discontinue toy production and turn to wartime priority products.

They restarted making wooden jigsaw puzzles in 1946 but found that the marketplace for jigsaw puzzles had changed due to the introduction of much less-expensive cardboard puzzles. The company’s wartime production had not included any need for the giant hydraulic presses needed to make cardboard puzzles, so their wooden puzzle-making increasingly focused on making children’s puzzles.

When Princess Elizabeth acceded to the throne in 1952 the company’s Royal Warrant was changed to read “Toymakers to H.M. Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother.” The Queen Mother is well-known to have been a huge life-long fan of wooden jigsaw puzzles. But that wasn’t enough: J. Salmon & Co. discontinued making puzzles in the mid-1950s. They continued to make other types of toys until 1978 when they were bought out by Palitoy.

The person I bought this puzzle from had been able to identify the date of its manufacture as being 1933 because puzzle historian Brian Sulman has published an “encyclopaedic work” on the Salmon’s Academy series. This puzzle appears in the their 1933 catalog, and that date is confirmed by the price label.

Although this was sold as a 150 piece puzzle the actual count was 165 pieces. Assembly was pretty straight-forward, but enjoyable because of the swirling cutting design. The artist of this genre painting is not identified and an image search bore no leads as to the artwork’s origin.

The only other research that this assembly inspired was to learn more about the reason for the red coats that are iconic for English fox hunting. I began wondering if they were to make it easier to find unconscious or dead bodies of fallen hunters but found no support for that theory. I did find theories relating them to military origins. It turns out that the cut of the coats (called “pinks” and never to be called jackets) is quite standardized with their swallow-tail backs, and that there were protocols governing the number and arrangement of their buttons, determined by individuals’ level of hunting experience and role in the hunt.

A Precious Load

Maker – Raphael Tuck & Sons Zag-Zaw brand London, England

Vintage – estimated 1920s

151 pc (count) 7.5” x 11.75” (3.8 cm²/pc) 4mm 3ply

German-born Rafael Tuck emigrated to London, England in 1866. He started out as a furniture maker, but began specializing in picture frames. That led to making and selling fine art prints, which in turn led to becoming a stationer whose products included printing that was of sufficiently high quality that he received a Royal Warrant from Queen Victoria.

Rafael Tuck & Sons was also very innovative, including being the first company to make picture post-cards and the first to commercially produce Christmas cards. Shortly before he retired in about 1882, Raphael Tuck’s company began making jigsaw puzzles.

The company proved innovative in that field too, and they were apparently the first to expand the subject matter of puzzles’ artwork so that they became a popular hobby for adults, and not just a teaching device for children. They are also credited with having invented the inclusion of figural pieces in the cutting design, using plywood instead of expensive and warp-prone hardwood sheets, and they pioneered making small die-cut cardboard puzzles (that used Tuck’s postcards as their artwork.)

As far as I can tell, when this family company was in its second and third generation of leadership they appear to have been the first company to mass-produce jigsaw puzzles in a factory format (as distinct from being a small craft studio) in response to an exploding fashion for jigsaw puzzle parties among the wealthy and upper-middle class in the first decade of the 20th century.

Rafael Tuck was the largest of the early makers and therefore had a head start going into the 1930s depression-era “Jigsaw Jag” in which teh puzzles became a very popul;ar form of entertainment among all levels of British society. But perhaps because they continued to offer only very conservative styles of artwork, they were soon eclipsed in England by Hayter’s Victory puzzles, J. Salmon’s Academy series, and the Chad Valley Toy Company during those booming times. I’ll write a more detailed essay about the Rafael Tuck company someday when I have more time.

This was my first push-fit puzzle. That means that the pieces do not interlock. In retrospect I wish that I had saved this puzzle for when I could have documented my progress in assembling it because it presented some interesting challenges for such a small puzzle (only 151 pieces.) But this is a case of my puzzling superpower of forgetfulness backfiring on me. I did not remember that this was a push-fit puzzle until after I had begun assembly.

The basic form for making pieces interlock in those years was to cut knob-shaped protrusions so that once adjoining pieces were assembled they would not become dislodged from each other. Initially, only the outside edge pieces were cut to be interlocking (possibly since cutting the interlocking knobs significantly slows down cutting on a scroll saw.) Having an interlocking edge creates a frame within which push-fit pieces are somewhat more stable. (I think that I recall reading that Tuck introduced the technique to the UK from Germany, but offhand I can’t find the source for that to confirm my memory.)

In the early 20th century makers began making fully-interlocking puzzles and featuring that as being a premium feature (see the photo of the Salmon Academy box for the previous puzzle.) Now, having at least a high degree of being interlocking is the standard expectation, and in most countries (except France) making push-fit puzzles has gone out-of-fashion except for some wooden ones that are still made by hand-cutters for fans of that style.

I know from discussion in the Wooden Jigsaw Puzzle Club discussion group on Facebook that push-fits are very much a love-it-or-hate-it kind of thing, with most people falling firmly in the hate-it category. I had been shopping for vintage push-fits to see which category I fell into, specifically looking for ones that were small enough to be starter ones for me. It turns out that this small one with lots of figural pieces (26 of them!) was a good choice to be my first push-fit puzzle. By push-fit standards it would be considered to be a very easy puzzle, but as a beginner with this format it gave me plenty of challenge. I thought it was fun and am ready to try some more (but I’ll stick to small ones, at least for now.)

The artwork of this puzzle is by Nora Drummond (1862 – 1949) and this style of rustic genre painting is typical of her work. She was born in Bath, England and was the niece of the acclaimed animal portraitist Haywood Hardy (whose artwork was used for the Wentworth puzzle that I reviewed in this posting.) In 1893 she married Daniel Joseph F. Davies and the couple emigrated to Alberta. She was one of the artists from whom the Rafael Tuck & Sons company commissioned paintings for their postcards, puzzles, and other printed products. Later in her life she moved to Victoria, the town where I live, located on the West Coast of Canada.

It was only during assembly that I realized that the painting’s name – A Precious Load – has two possible meanings. A young boy, presumably the farmer’s son, is also on the overflowing hay-wagon.

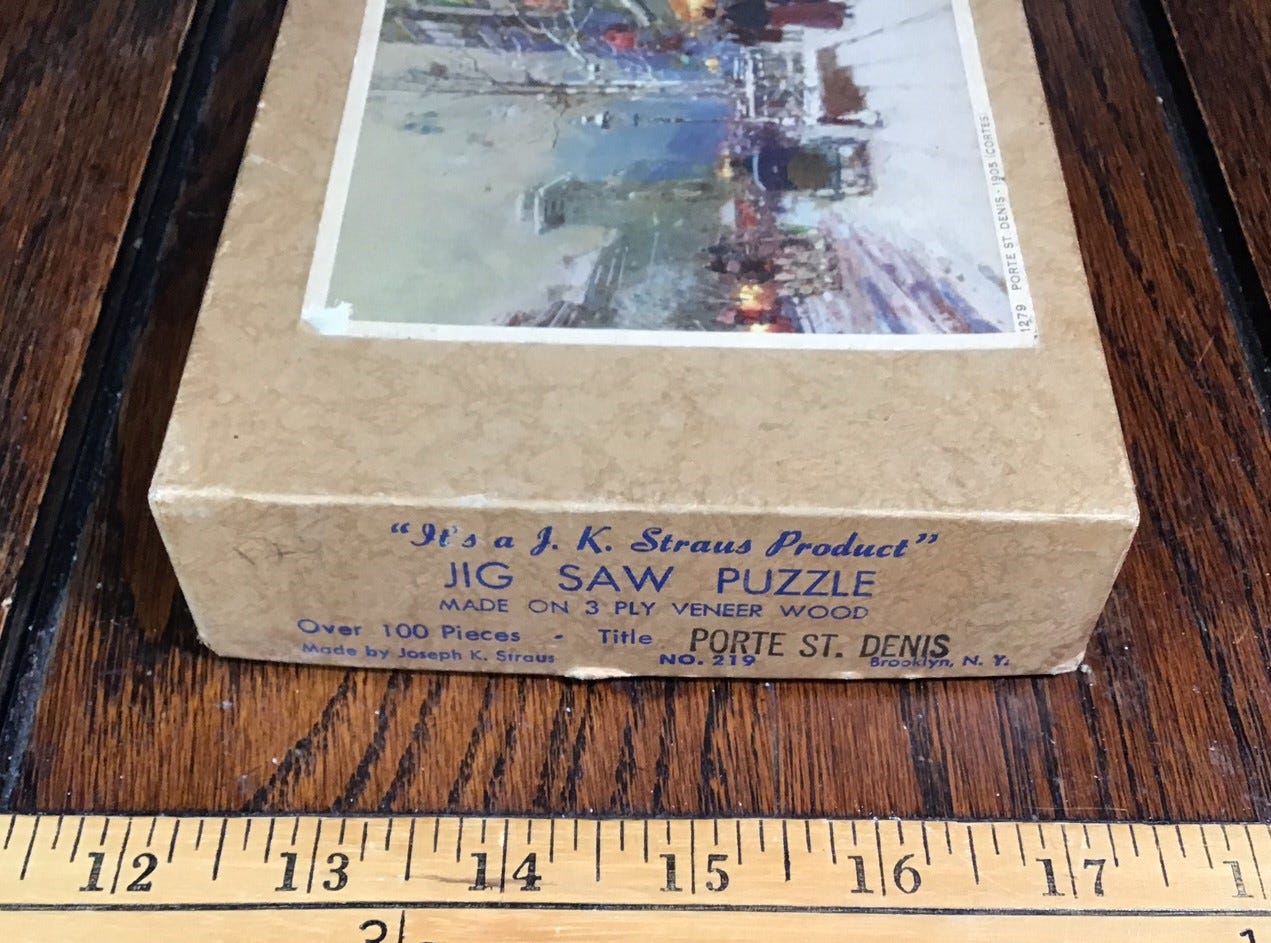

Porte St. Denis 1905

Maker – Joseph K. Straus Brooklyn, N.Y.

Vintage – estimated ca. 1950

101 pieces (counted) 7”x 9¾” (4.3 cm²/pc) 5mm 3ply

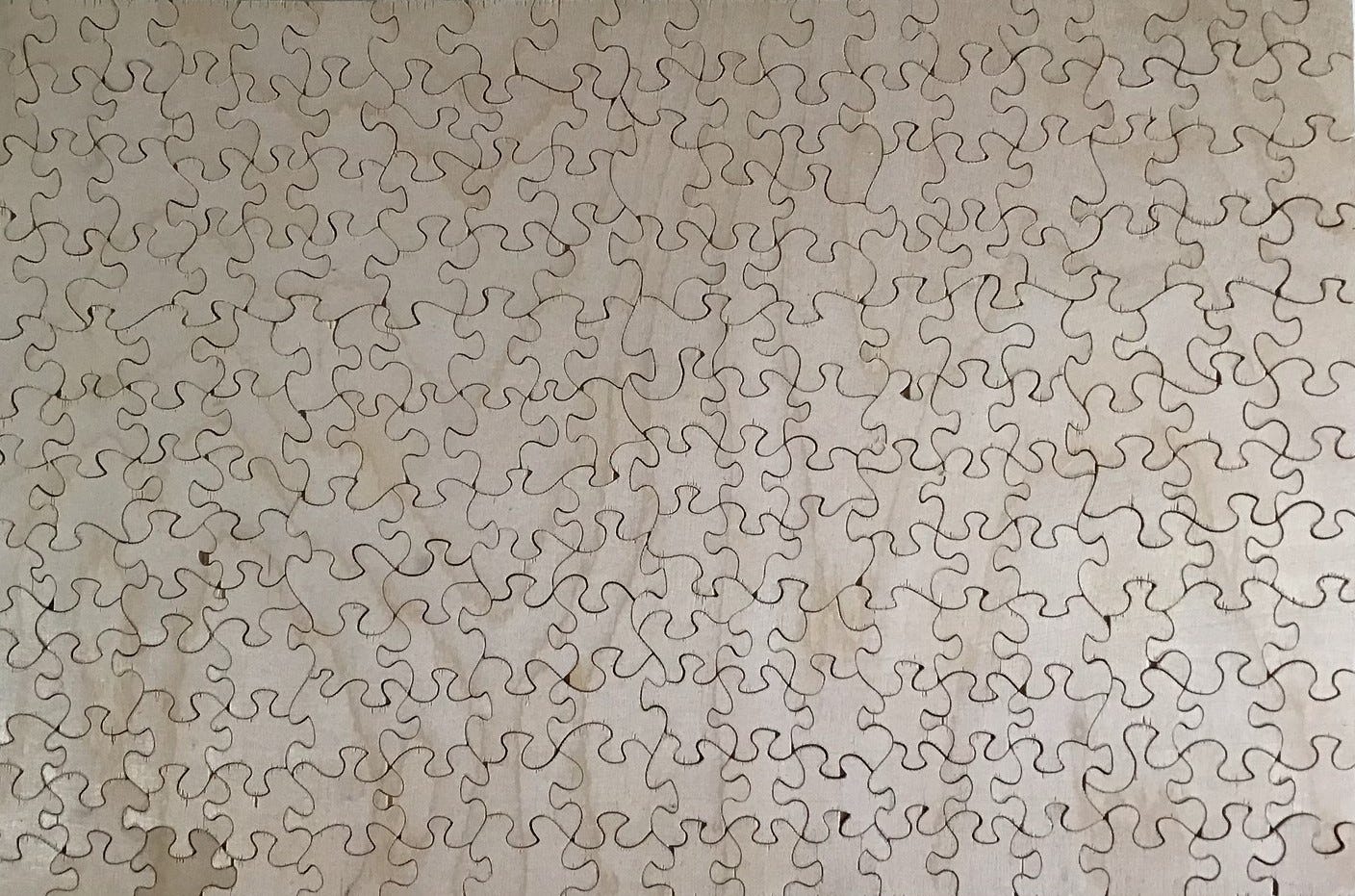

At only 101 pieces, and 7” x 9¾”, this urban winter scene is the smallest of the puzzles that I assembled during this midwinter-season vintage binge, and being strip-cut with continuous horizontal and vertical cut-lines (what in the world of cardboard puzzles is called random cut) it also has the simplest cutting design . Add in an image that gives lots of clues, and it was by far the easiest.

The strip cutting format was frequently used for puzzles made by the company that Joseph K. Straus and his wife ran for over four decades, from 1933 until 1974. Straus originally worked for Ullman Manufacturing, a fine art publisher and manufacturer of “framed pictures and art novelties,” including some jigsaw puzzles. In 1933 he set up his own puzzle business, renting space from the Ullman company. In their later years, Straus’ products included die-cut cardboard children’s puzzles, making them the only hand-cutting company that I know of which adopted that technology.

From my research I have been able to get no sense of the scale of Straus’ operation as a maker of adult puzzles. Jigsaw puzzle historian Anne D. Williams describes them as being one of the largest of the American wooden puzzle makers. But that may be more due to the company’s longevity and the popularity of their children’s puzzles than their size as a maker of adult puzzles. It was only later in 1957, when they were primarily making children’s puzzles, including die-cut ones, that they incorporated. This puzzle was made prior to that incorporation; the box merely says “Made by Joseph K Straus”.

The whole time that I was assembling this puzzle I assumed that Porte St. Denis was a Port town, and I wondered whether it was in the US or France. Also, since this appears to be an urban location I wondered why I had never heard of the place. Actually, the name is a reference to 17th century arch known as Porte Saint-Denis, seen rather inconspicuously in side-view on the left side of the puzzle’s image. It is a prominent landmark in the city of Paris.

Porte Saint-Denis was the first of four triumphal arches that have been erected in Paris over the years. The 25 metre tall arch was built in 1672 by King Louis XIV to commemorate victories over Holland under his reign. It is located where the northern gate into the City had once stood, though walls built by Charles V in the 14th century. Those walls had only recently been torn down under the reign of Louis XIII to be replaced by new walls around the expanding City, and the name of the old gate stuck to Louis XIV’s arch. (There have been seven successive rings of walls around Paris over the years.) From the Sun King’s perspective I suppose that is unfortunate since now hardly remembers the reason for the arch or who had it built (although he still is remembered for other accomplishments.)

The image for this puzzle is an early painting by the renowned Spanish-French artist Édouard Leon Cortès (1882–1969.) Cortès was born in France but his father had been a painter for the Spanish Royal Court. The younger post-impressionist Cortès is known as "Le Poète Parisien de la Peinture" (the Parisian Poet of Painting) because of his many Paris cityscapes in a variety of weather and night settings. There are other biographies of him here and here, as well as his Wikipedia entry, and here is a gallery with over 200 of his paintings.

The artist was a life-long pacifist, but also patriotic and lived during a time when his country was twice besieged by war. During the Great War when the front approached his home, Cortès joined the retreating French infantry regiment and was immediately sent to the front lines. There he was wounded by a bayonet and ended up in the hospital. After his recovery the Army found a more appropriate use for him drawing maps. Despite his obvious love for France, throughout his life he turned down all military and civilian recognition, including refusing to accept the highest French order of merit, the Legion of Honour.

By the 1950s many of his Paris streetscapes still showed horse-drawn carriages and styles of clothing long-vanished from the real streets of the city. When asked why, he stated that he wished simply to halt history at 1939, before the trauma of the Second World War changed Paris irrevocably.

The Band of the Life Guards in State Dress

Maker – Raphael Tuck & Sons London, England

Vintage – early-mid 1930s

220 pieces 9¾” x 15” (4.2 cm²/pc) 4mm 3ply

This puzzle was made by Raphael Tuck & Sons, the same company that made A Precious Load (above.) But you will notice that its packaging looks quite different with bright colours and a picture of the artwork (actually, as postcard glued down) on the cover. Also, this one isn’t push-fit and doesn’t have figural pieces, and it doesn’t have the brand name Zag-Zaw like its earlier sibling.

That is because, like its competitors, the Tuck company expanded during the early years of Great Depression and began to produce less-expensive puzzles to fill the booming demand for jigsaw puzzles from the lower-middle and working-classes. Rather than put the reputation of its traditional Zag-Zaw brand at risk, but still capitalizing on its reputation as a longstanding maker, this is now just a Tuck’s Picture Puzzle. Tuck still made Zag-Zaw branded puzzles, but they were its higher-end product. Those included the figural pieces that slowed down cutting and made the puzzles more expensive, and Zag-Zaws continued not to include what many of their customers considered to be an unwanted indication of what the puzzle would look like when it was completed.

I wouldn’t normally buy a puzzle with military imagery but this one is more musical than military, and besides, it is so colourful that I couldn’t resist. This is #5 in a series of six puzzles with ceremonial images called Soldiers of the King. Dating of the puzzle is aided by the dress uniforms bearing the insignia of King George V.

There is an apparent signature in the lower right-hand corner of the puzzle – “Carfax”. That isn’t the name of the artist but is an indication that the image was provided by The Carfax Gallery in the fashionable St. James’ district of central London. Carfax exhibited both Old Masters and contemporary art, but is best known for exhibiting work by the members of the New English Art Club and the Camden Town Group, and for making licensing arrangements like this for their paintings.

While the Carfax Gallery is now long gone, that type of anonymous licensing for anonymous use of painters’ and photographers’ artwork continues today. That is why the identity of the artists who make many new puzzles’ images is often not stated, and why such an omission should not necessarily be interpreted as an indication that the artwork has been pirated. It is still a stigma for artists to be considered to be seen as “only commercial illustrators.”

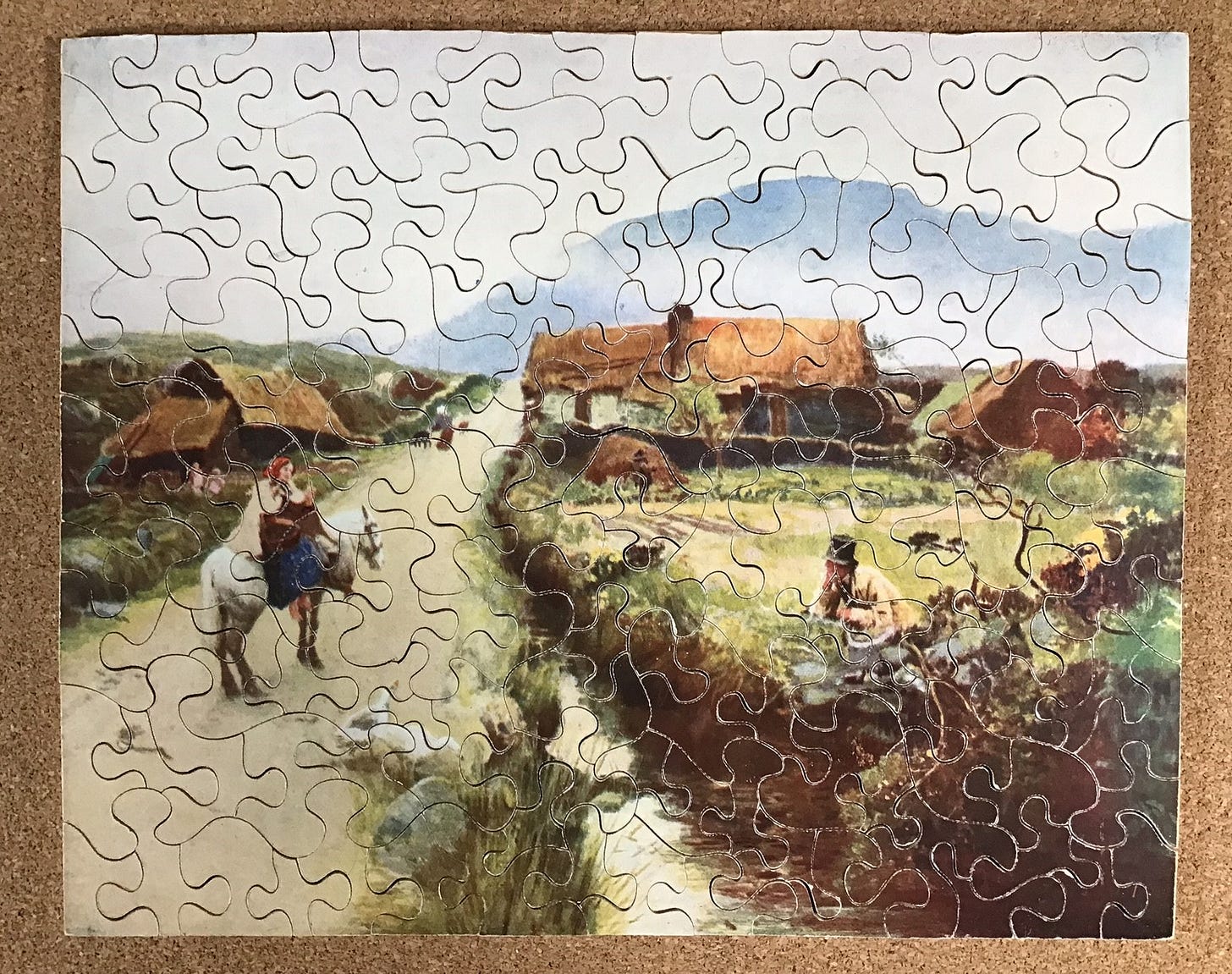

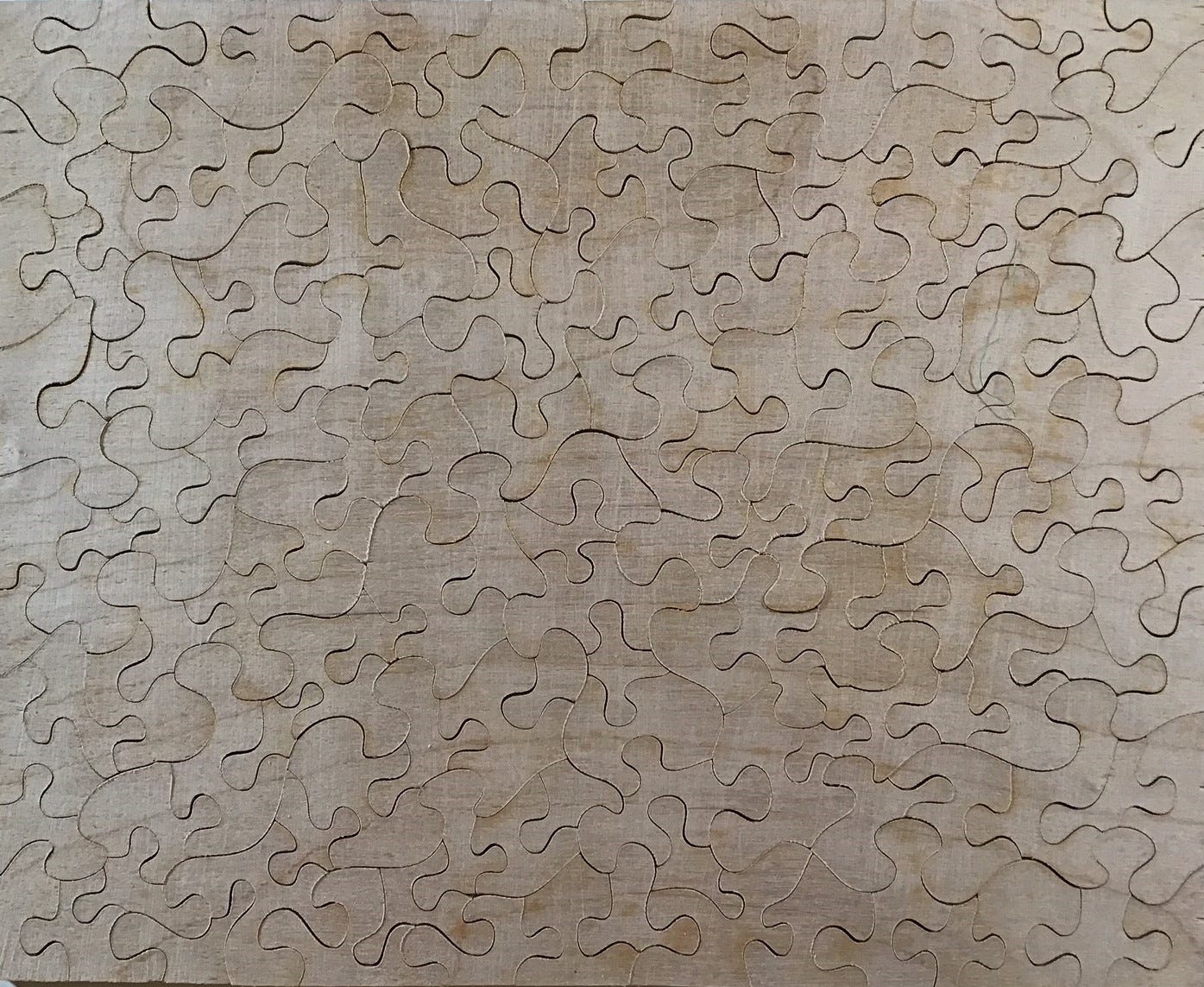

Wayside Gossips

Maker – J. Salmon & Co. Academy brand Sevenoaks, Kent, England

Vintage – 1932

146 pieces (count) 8”x 10” (3.5 cm²/pc) 4mm 3ply

This puzzle is called Wayside Gossips but my impression is that the young woman on the horse and the top-hatted man in the field are flirting.

This is another Academy brand puzzle from J. Salmon & Company, and its 1932 date of manufacture is identified from the same source as Before the Hunt (above.) It has the same baroque cutting style as that one.

Also like that other Salmon’s Academy puzzle, this is an unsigned everyday rural “genre” scene, and again an online Google image search came up empty as to the identity of the painter. The main thing that I infer from that is only that the original painting has not come up for auction or sale from an art dealer who gave it even a tentative attribution or who submits information about their sales or offerings into any of the online art data bases.

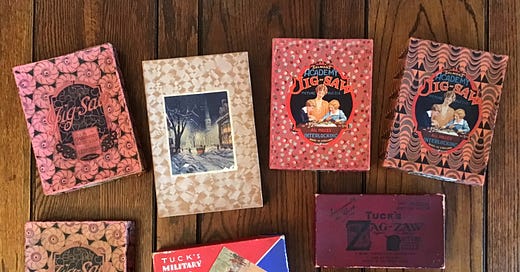

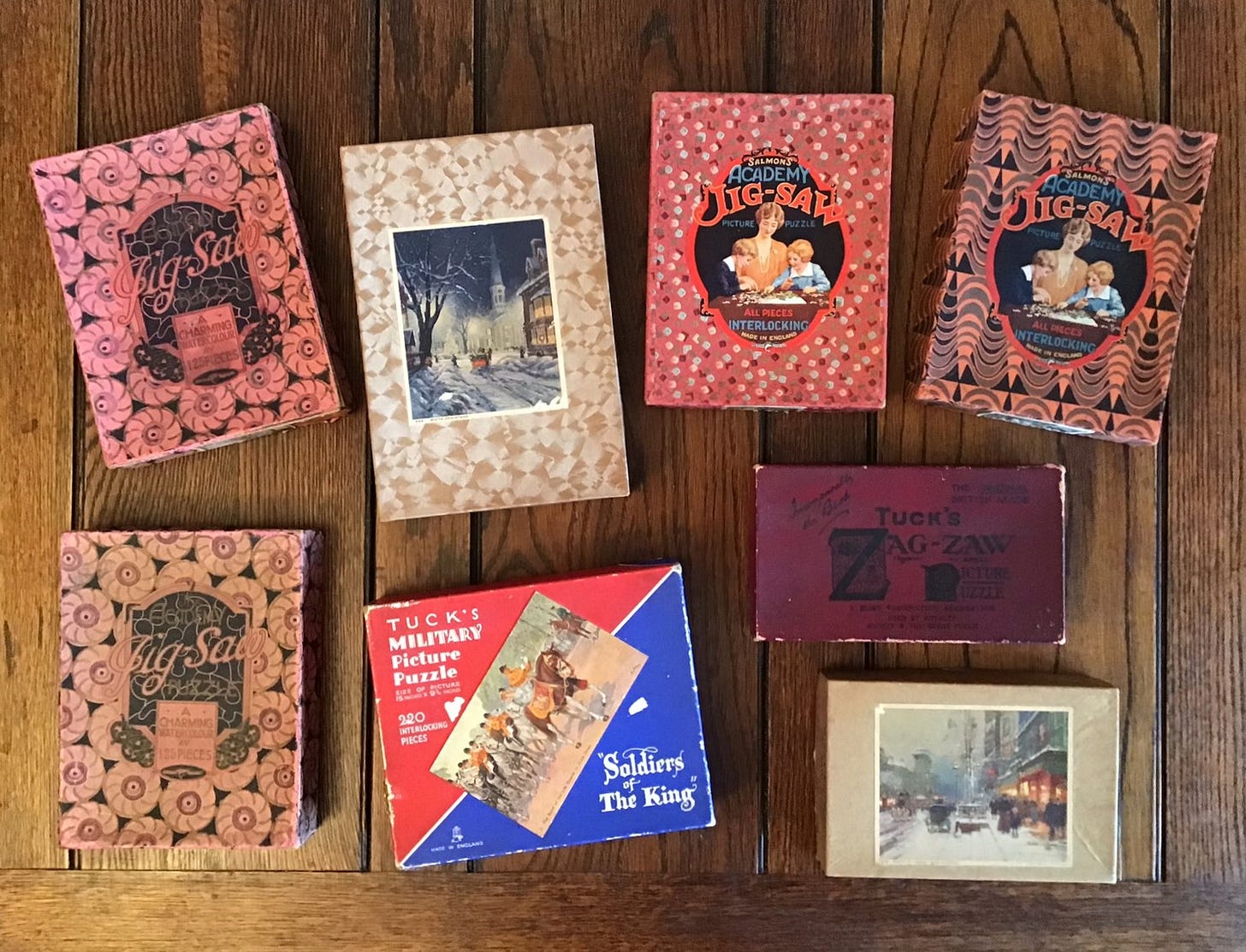

The box that held this 1932 puzzle is similar to the one that held Before the Hunt, dated 1933, but with a different pattern of red paper decorating the box. I know that in those days the highly-respected puzzle-maker Enid Stocken who cut puzzles in her home workshop, would decorate various used boxes with wallpaper to make frugal but attractive packaging for her puzzles. I assume that box decorating was one of the jobs in a Depression era puzzle factory.

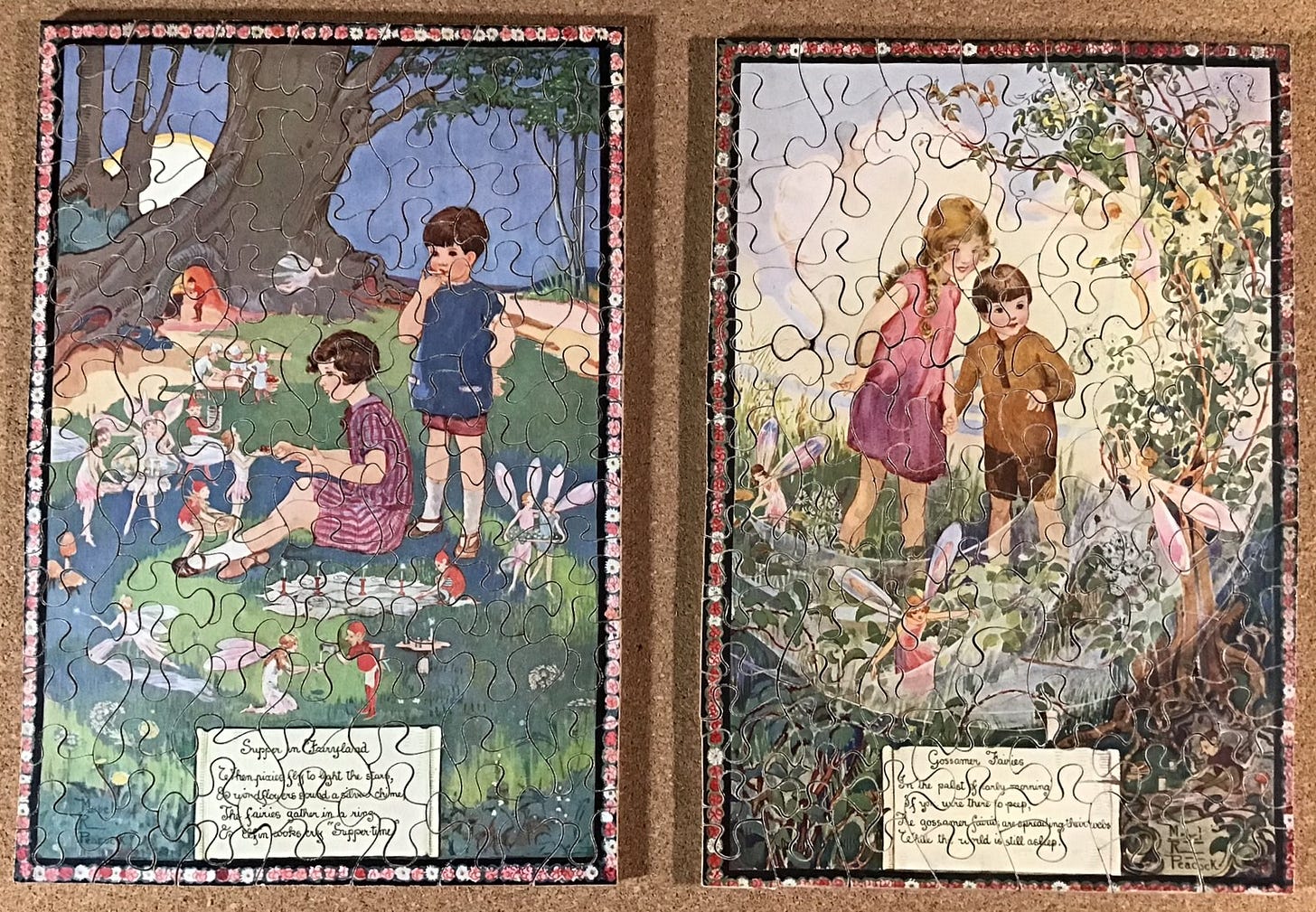

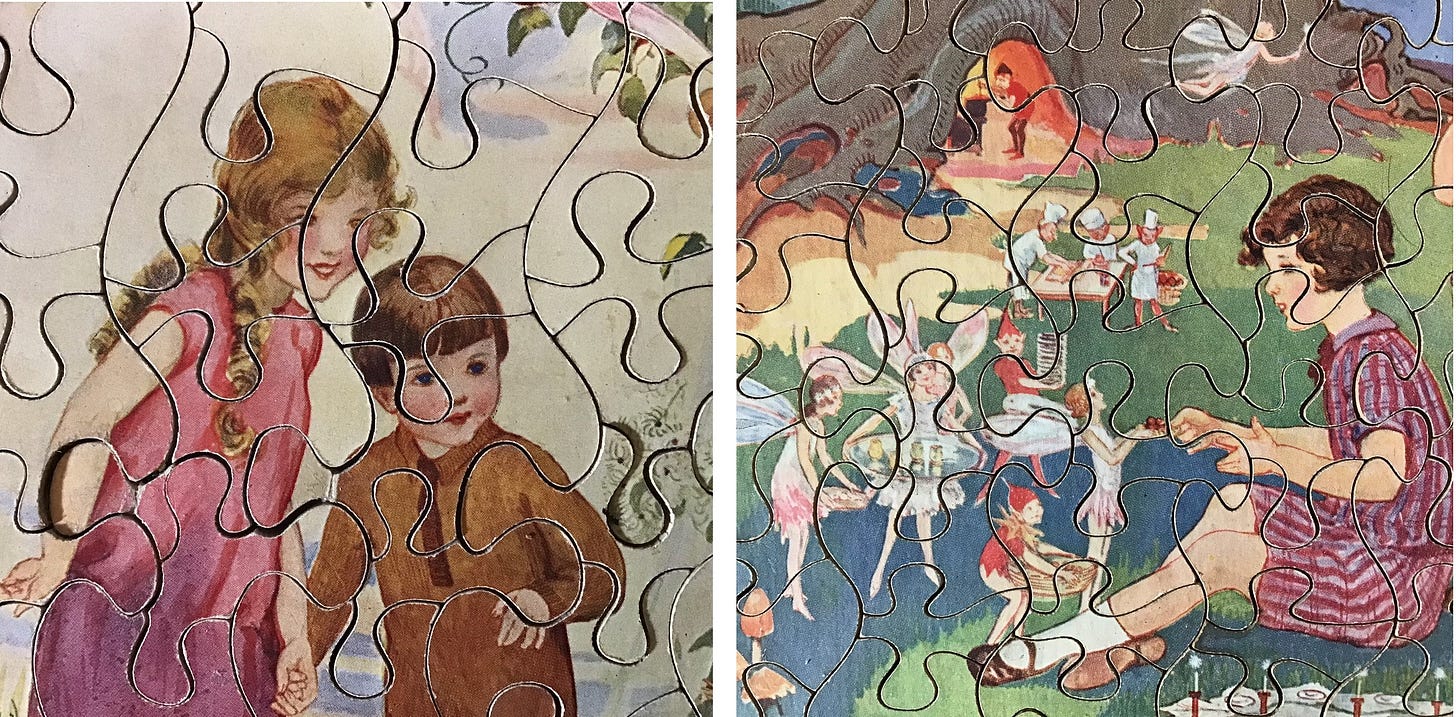

Gossamer Fairies and Supper in Fairyland

Both made by J. Salmon & Co. Academy brand Sevenoaks, Kent, England

Vintage – Gossamer Fairies – 1929; Supper in Fairyland - 1932

Both – nominally 125 pieces 10”x 7” (3.6 cm²/pc) 4mm 3ply

These are two more puzzles from Salmon’s Academy. Both are only 125 pieces. I bought them from an eBay auction as a pair and decided to assemble them that way too, by mixing up the pieces from both boxes. I had read about doing puzzles that way in the Facebook group but had never tried it before. It worked out quite well.

Gossamer Fairies, made in 1929 on the bottom, and Supper in Fairyland, dated 1932 on the top, are apparently both made earlier than the previous two Salmon’s Academy puzzles. Their boxes are exactly the same size and also are decorated with faded red “wallpaper”, but they have a different large sticker on top identifying the company. Note that this older style sticker does not say “All pieces interlocking” like the one that replaces it. (Note: Also interesting is that the small image of the completed Gossamer Fairies puzzle has been removed, I suspect by or on behalf of an old-school assembler who did not want to know the image in advance.)

The artist for both images is Mabel R. Peacock, a British book illustrator who was active from 1920 until the early 1950s. I was not able to find much information about her online, but most of the books she illustrated appear to be fantasy and children’s literature, or with biblical and other religious themes. Near the end of her career she illustrated Enid Blyton’s (author of the Noddy children’s books) The Greatest Book in the World.

Here are a few more of Mabel’s illustrations I found online:

Combining the two puzzles together not only added to the challenge but it also gave me more time to appreciate the artwork. This is one of those puzzles where much of the fun is discovering little details in the image as they emerge.

All in all, I would say that this was the most fun assembly of this midwinter vintage puzzle binge.

White Christmas

Maker – Joseph K. Straus Brooklyn, N.Y.

Vintage – estimated ca. 1950

300 pieces (nominal) 16” x 11¾” (4.0 cm²/pc) 4.5 mm 3ply

In contrast to the colourful fairies puzzles, this 300 piece one from Joseph K. Straus was my least favourite one from the puzzle binge. While assembling it I came to think of its name, White Christmas, as being ironic since it is the darkest puzzle that I have yet assembled.

The image is a painting by Carl Ivar Gilbert (1882-1959). I was not able to find much information about him online except that he painted still lifes and marine scenes, and urban scenes like this in New England and in New York City. But I did find the following painting of a different New England church that appears to have been painted within a day or two of the puzzle’s image. This painting was sold at a Sotheby’s auction in 2019. Because of its colourfulness and composition I think that assembling a puzzle made with it would have been more enjoyable.

During assembly I had some fun trying to determine when and where the picture had been painted, although I was not able to pin it down. The two churches have rather distinctive steeples of a type that one associates with New England. But I couldn’t find any matches by doing a cursory image search online. Since the two churches are probably within fairly close proximity to each other the “where” could probably be identified from further research.

With regard to ”when” I got a bit closer to a tentative answer. The shape of the car (especially the rake of the windshield and the humpback profile behind the passenger compartment) in the picture suggests that it is from no earlier than about 1938 to no later than the early post-war years. Both cars in the Sotheby’s painting appear to be from the 1930s.

The harsh, bright, blue-white street lights on fairly tall lamp-posts appear to be arc lighting. I became intrigued by that technology several years ago when I learned that my home city of Victoria’s first street lighting was five arc lights at the top of 150 foot tall poles. Arc lighting was the first commercially-successful form of electric street lighting and was much brighter than the street lighting we are used to these days. But it was a relatively short-lived technology because it had high maintenance requirements.

The gap between arc lights’ iron “pencils” (between which the electricity arcs, creating the bright light) needed to be adjusted frequently, as well as them having to periodically be inspected and replaced. Those jobs involved workers climbing the lamp-posts to maintain them. Arc lights also made a buzzing sound, and after radios became common they led to complaints about radio interference. Therefore, most cities that had installed arc lights for their street lighting replaced it fairly soon after better alternatives became available. Until the early 1950s all of the choices would not have appeared to be this bright, or they would have given off a “warm” rather than “cool” tone of white.

So, unless the artist took liberties with the depiction of the lighting, I suspect that this image was painted in the very late 1930s or the early 1940s at the latest. That could probably be pinned down if I could find more information online about when there was a fairly large snowfall in New England shortly before Christmas during that time window.

The cutting of this puzzle is basically a grid cut. For this puzzle I did take photos of my assembly progress because I was able to complete the outside edge before beginning on the interior. That is common for cardboard puzzles but this was the first wooden puzzle that I could do it. But then I was not able to make much progress working from the outside in, so had to start from the colours of the car, church windows, and Christmas tree and assemble outward from there

You can see that the cutter first cut across the 16” x 12” board with a continuous cut-line with lots of alternating connector knobs up and down, then similarly cut those in half to make more manageable sized portions of the puzzle to work with. I have often seen that approach to cutting in other puzzles but I haven’t bothered to mention it before.

You make the following statement about interlocking puzzles:

The basic form for making pieces interlock in those years was to cut knob-shaped protrusions so that once adjoining pieces were assembled they would not become dislodged from each other. This method was invented in Germany sometime in the late 19th century. Initially, only the outside edge pieces were cut to be interlocking (possibly since cutting the interlocking knobs significantly slows down cutting on a scroll saw.) Having an interlocking edge creates a frame within which push-fit pieces are somewhat more stable. (I think that I recall reading that Tuck introduced the technique to the UK, but offhand I can’t find the source for that to confirm my memory.)

This is simply not the case. I have puzzles from the 18th century and early nineteenth century that interlock around the edges.

Dear Bill,

You've provided quite a "feast" today, with so many small puzzles featured. My favourite, in terms of image, is "A Precious Load," though I like best the story you've told for "The Band of the Life Guards in State Dress." I agree with you that it is a little bit regrettable that you no longer have this first (for you) push fit puzzle, if for no other reason than that you could compare it to other puzzles in your collection. I felt quite engaged with the story of Édouard Cortès. I also think the puzzle entitled "Wayside Gossips" would be more appropriately entitled "Wayside Flirts." In any case, thanks for all your work.