Three more from StumpCraft

Reports on Badlands to the Bone, Urban Treehouse and Tea from the Void, all of which feature recent images by contemporary Canadian artists. (About 4500 words; 63 pictures)

I have several StumpCraft puzzles sitting on shelves in my living room that I have yet to assemble. Just seeing those treasures there gives me the joy of anticipation and a feeling of abundance. After my recent focus on vintage puzzles and smaller laser-cut ones I thought that it was time to treat myself to a StumpCraft binge.

This posting complements my previous reports about StumpCraft puzzles:

The history of StumpCraft (essay)

StumpCraft retro-reviews (5 puzzles)

In summary, StumpCraft is a laser-cutting puzzle company in Calgary, Alberta that was founded in 2017 by Jasen Robillard. It is now widely regarded as one of the very best laser cut puzzle-makers in the world. Time and time again their puzzles have delighted me with their well-curated images by Canadian artists, rich colours (UV printing on wood), excellent fabrication on over 6mm thick mdf (American nominal “¼ inch” thick puzzles are actually only 5 mm), and they have among the best overall cutting designs and figural pieces of any makers today. It makes me proud that such a top-notch puzzle-maker is a relatively small Canadian company.

Because StumpCraft’s design and fabrication standards are of such consistently high quality, to avoid repetition with my previous postings these reports are not written as puzzle reviews. (For a StumpCraft review, see here.) Basically, this posting is three separate essays which are mainly pictorial assembly walk-throughs and comments, and background information from my research into each puzzle’s image.

These three puzzles do nothing to lower StumpCraft’s standing as being among my favourite puzzle-makers, and if I take into account the convenience and lower shipping cost for me because they are a Canadian company, it is my very favourite maker.

I present these three puzzles in the chronological order in which I assembled them in the StumpCraft binge, rather than the order in which they were designed and introduced. The puzzles and their design dates are:

Badlands to the Bone (2019)

Urban Treehouse (2022)

Tea from the Void (2018)

Badlands to the Bone

A stretch of the Red Deer River Valley in Alberta about a two hour drive east of Calgary, is famous for two things. One is its spectacular landscape of lush river and stream valley bottoms, and the surrounding dry desert hills that include intriguing formations called hoodoos. That itself would have been enough for that part of the valley to become a provincial park.

But the region’s main claim to fame is that its dry eroding desert hillsides have yielded over 5% of the world’s dinosaur fossil skeletons, and they continue to yield new treasures every dig season. Nearly 60 species have been discovered there to date! It is for that reason that this valley is world famous and the area has been declared by UNESCO to be a World Heritage Site. Nearby, in the town of Drumheller, is the Royal Tyrell Museum, one of the world’s top paleontology museums and research facilities.

Interestingly, while the park is known for its abundant dinosaur fossils, the Bearpaw Formation that overlies it contains marine fossils like ammonites, sharks, and mosasaurs. Yes, you read that correctly; the layer that has fossils of ocean-dwelling critters is above the dinosaur layer.

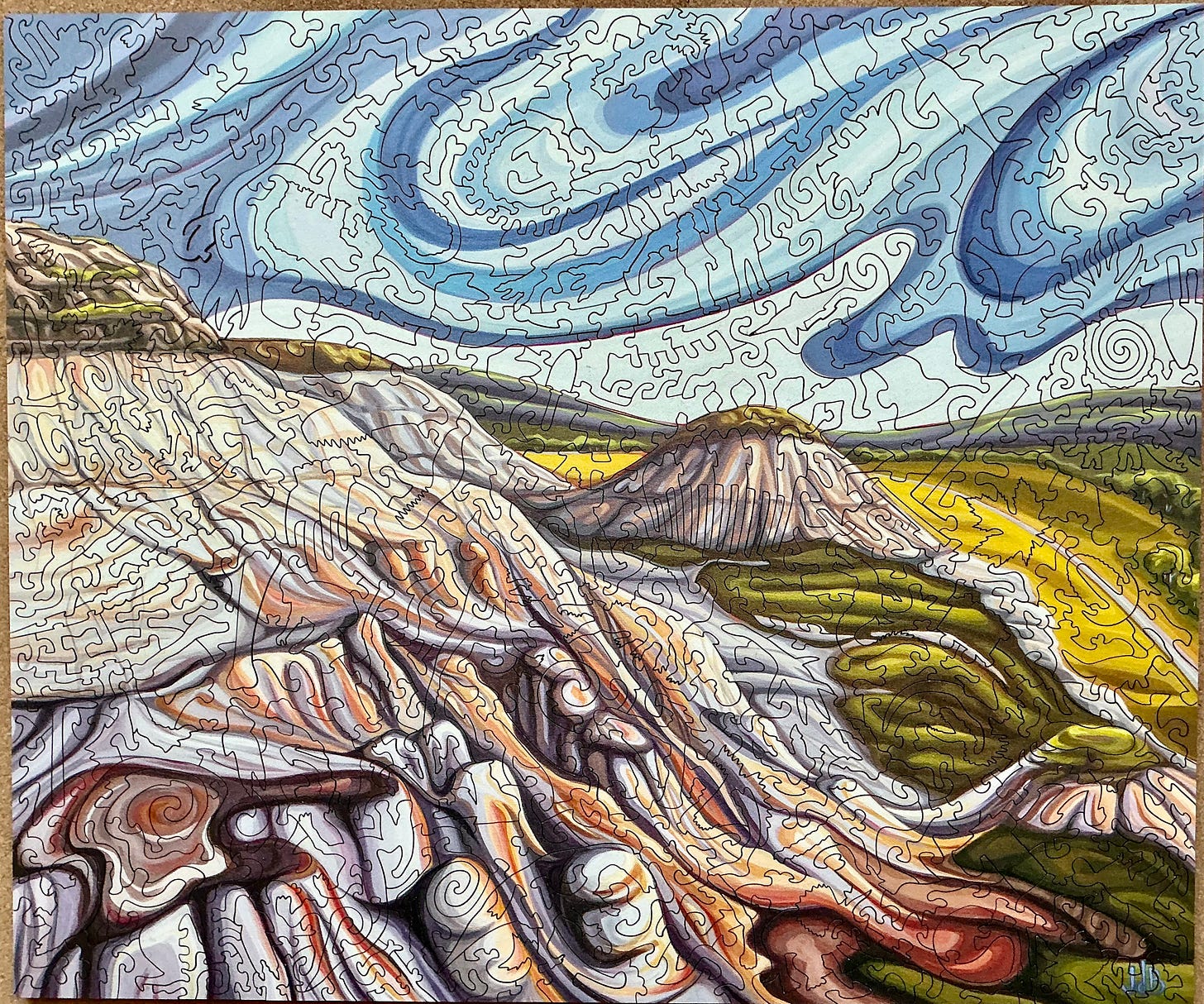

This puzzle’s image is a 2019 collaboration between StumpCraft’s founder Jasen Robillard and Alberta artist Julie deBoer. Jasen had been thinking about making a dinosaur-themed puzzle using a painting of the exotic landscape in Dinosaur Provincial Park ever since founding StumpCraft. He was keeping his eyes open for an appropriate image that captured the spirit of the place.

When he saw Julie deBoer’s signature big-sky landscape paintings Jasen recognized that the style she uses in her swirling skyscapes would perfectly fit his own impressions of the Badlands landscape. It would also be perfect for the cutting design that was developing in his creative imagination. When he approached Julie to commission such a painting she immediately agreed. She herself had many fond memories of exploring in the Red Deer River Badlands, both as a child and as an adult with her own children. You can read all about their collaboration in Jasen’s Deep Dive Design essay about this puzzle.

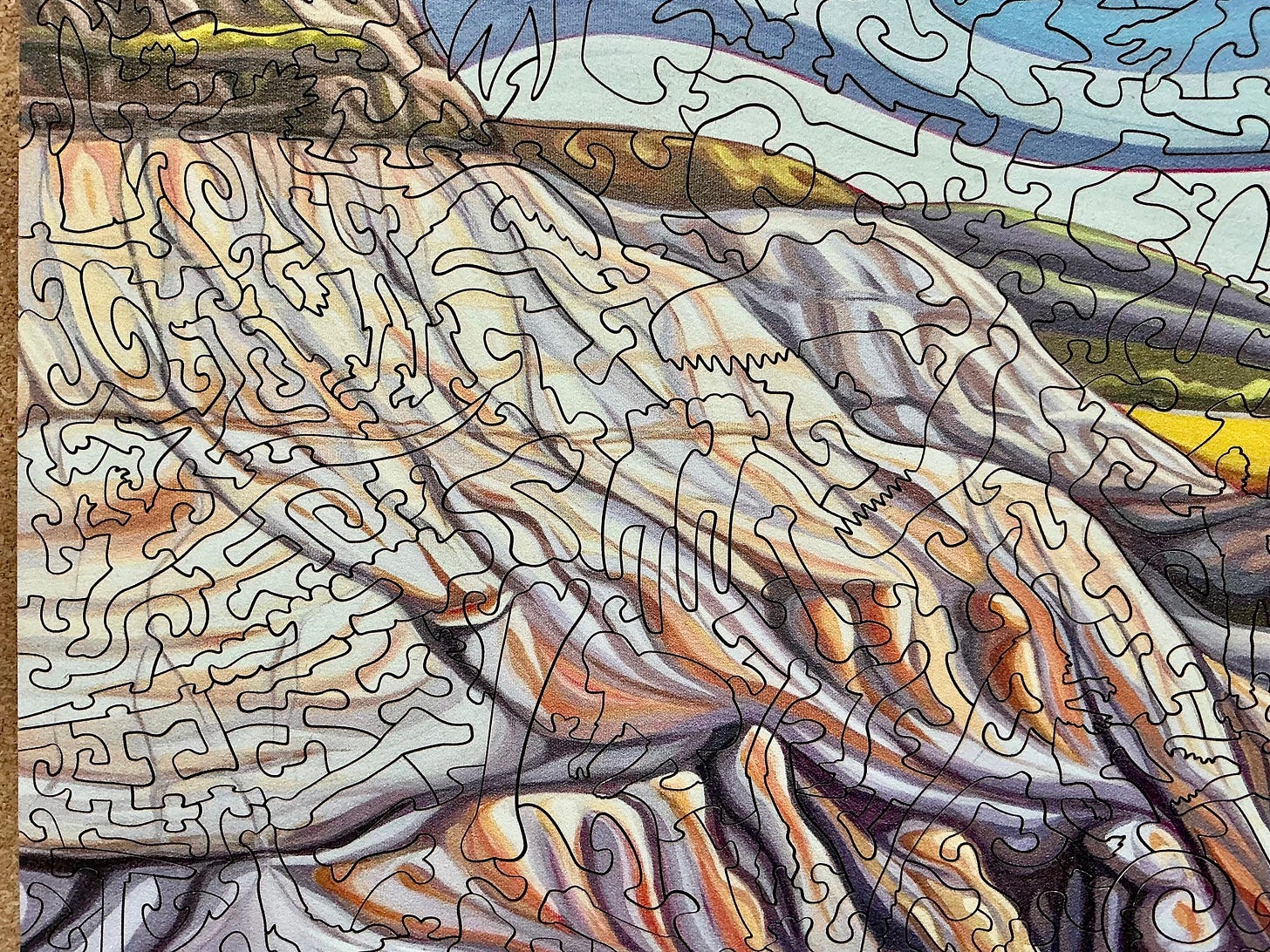

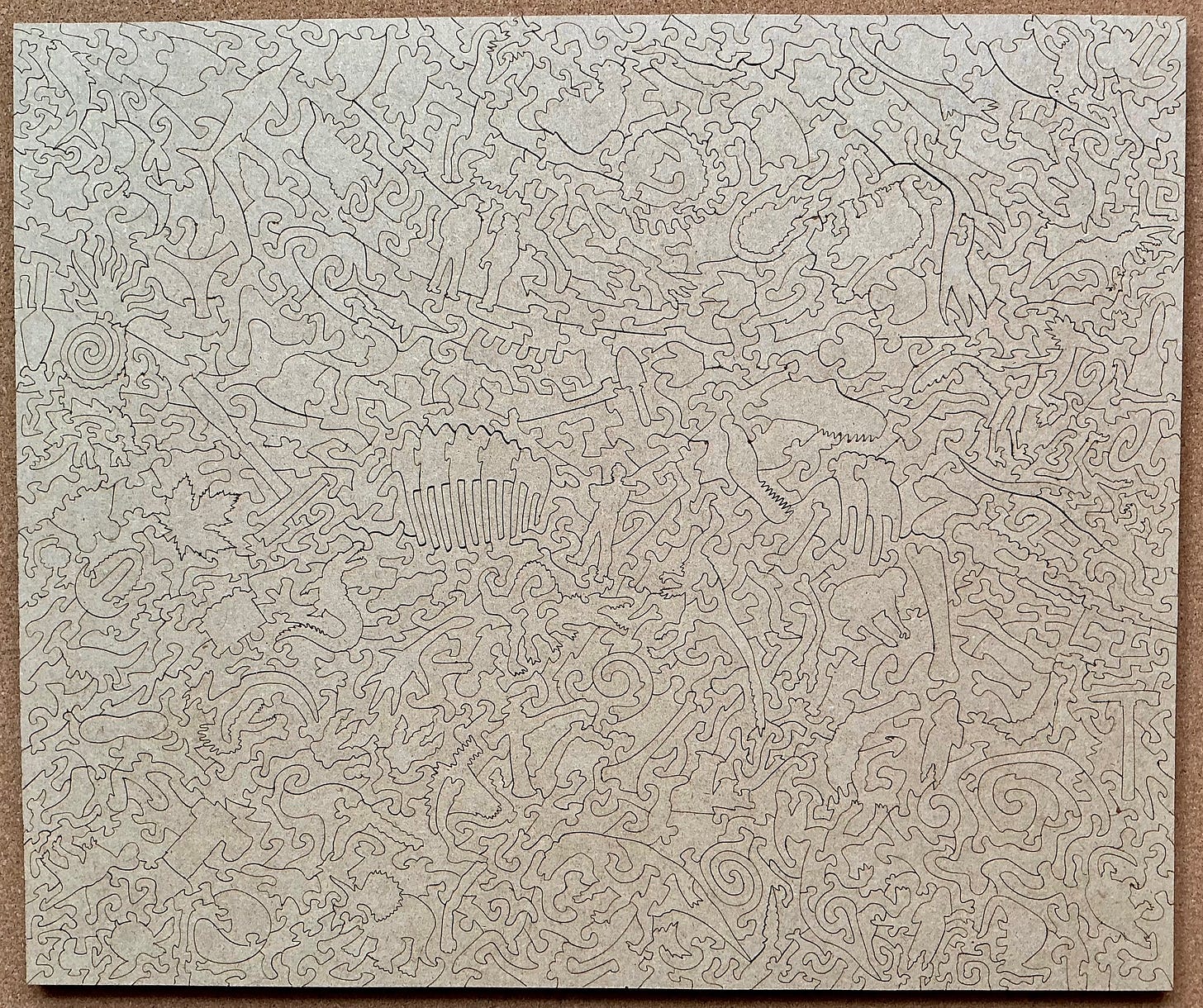

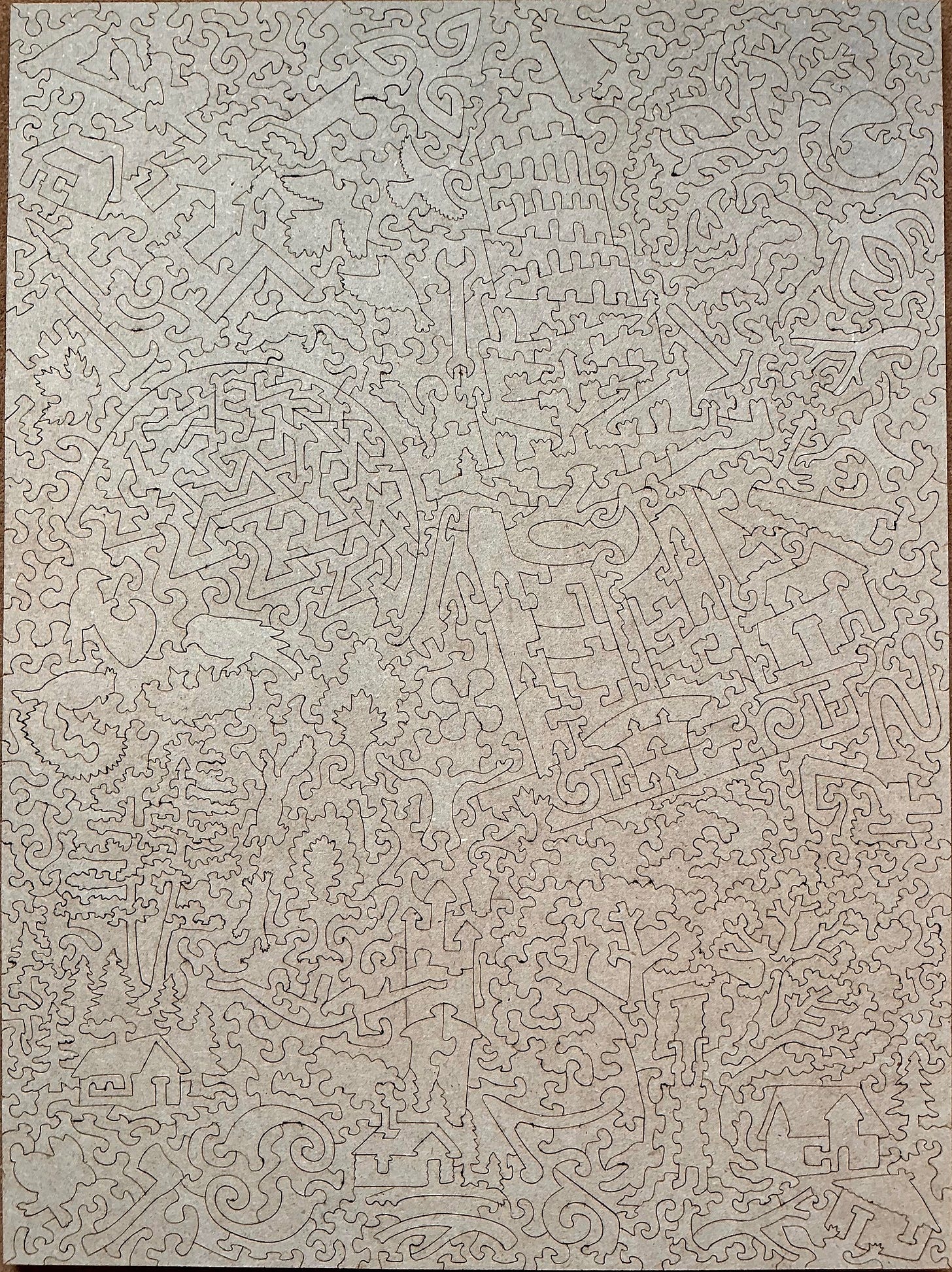

As you would expect, Jasen’s cutting design for the puzzle includes figural pieces of dinosaurs and bones, which would be the obvious choice for that fossil-rich landscape. But Jasen takes it further: Many of the non-figural pieces include only parts of dinosaurs and fossils so that the overall impression is that of a fossil bed:

As you can see, as always Jasen used a variety of ways to make his pieces interconnect in addition to the tried-and-true knobs, earlets, or other protruding connectors with their matching sockets. This variety makes each individual piece seem like a little abstract work of art in its own right.

On balance, this is one of my favourite StumpCraft puzzles yet, and that is really saying something because StumpCrafts have long been among my very favourite puzzles.

Assembly

[Spoiler Alert: The following content includes photos and discussions of assembly of the puzzle. If you already plan to buy Badlands to the Bone you may want to skip this part to preserve the surprise elements for your own assembly. On the other hand, if your visual memory is as poor as mine seeing these pictures may be harmless. This same warning applies to the assembly walkthroughs of the other two puzzles.]

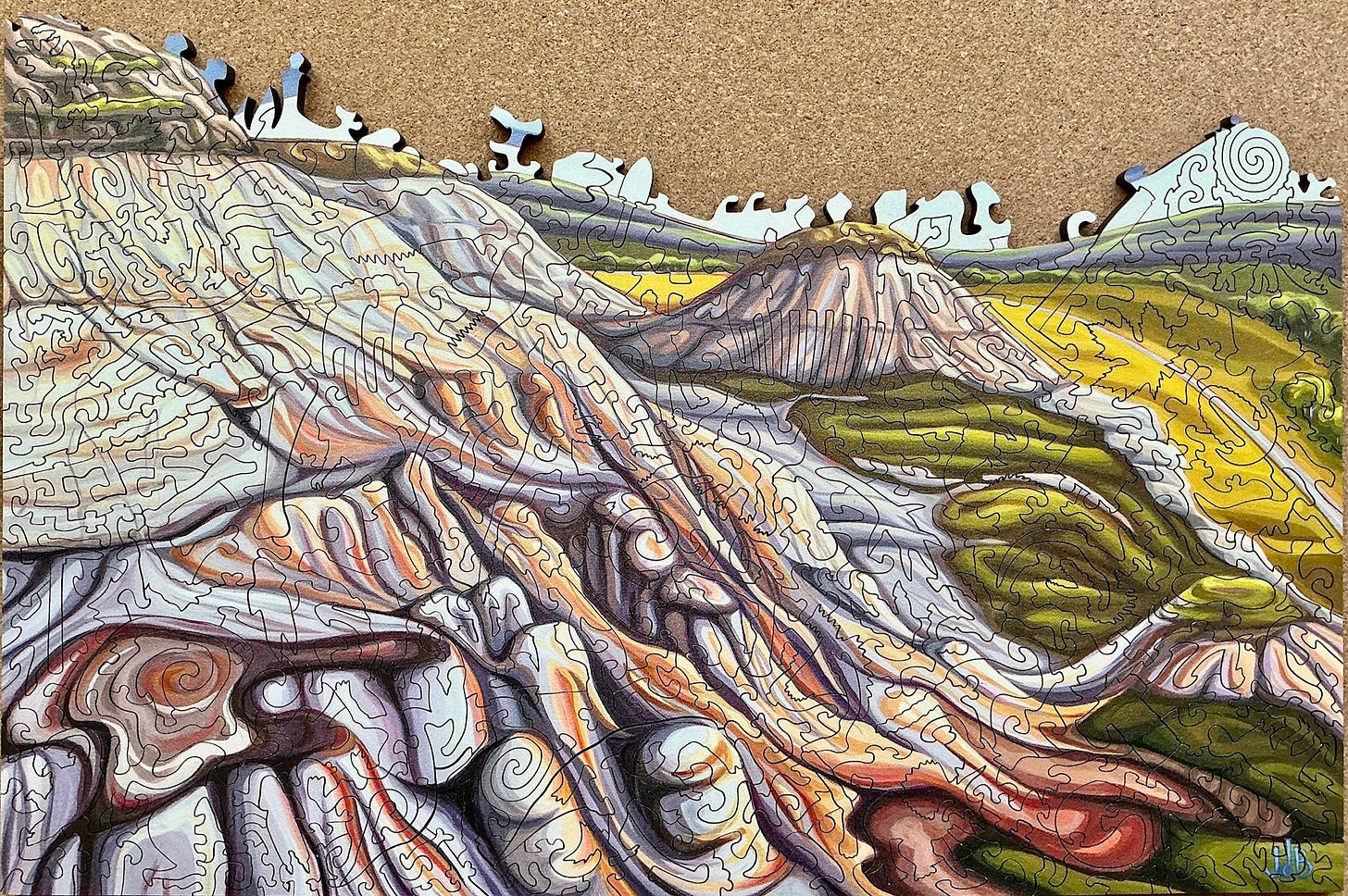

I knew from the beginning that this puzzle would be tricky despite its abundance of whimsies. Jasen’s puzzles are always tricky. StumpCraft rates it as 4 out of 5 difficulty, and I have learned to believe their ratings. I knew that its 541 pieces would require sideboards. As I was flipping I saw that a fair proportion of the pieces were blue and/or white and appeared to be sky. I decided that they would be the ones to go into the Lindt candy box-tops that I use as sideboards when my cork ones are otherwise occupied.

The sorting itself was very superficial, only separating out the figure pieces, some spirals (on the lower right), and a colour sorting of the relatively few pieces that were yellow and/or green (on the lower left.)

After I took the above photo I flipped over the figural pieces. I also moved pieces around both to create a better, but still rough, sorting by predominant colours and to give myself some working space.

One of StumpCraft’s signature whimsies, a maple leaf, was yellow and green. I knew from experience that its distinctive outline makes for easy shape matching so I was able to get off to a quick start.

The spirals were another easy target of opportunity for making small assembly islands, as were several pieces that had long, straight projecting lines. I didn’t have their colours grouped together on the board, but because many of the pieces had two or more such projections they were easy to find in the dense muddle of multi-coloured pieces. I thought of that sub-assembly as a comb, but in this context I presume Jasen meant them to represent the distinctive sail-like structure on the back of a dimetrodon.

I continued by focusing on the dark green and then dark red, and was quite pleased when I found I could attach the dimetrodon assembly to a growing green one. I also continued to look for opportunities to match up individual pieces based upon distinctive shapes, like the sharp teeth in the medium-size assembly on the left in this picture:

I remembered just enough about the image of this puzzle to know that I didn’t remember anything that would aide much with assembly. The painting is a rather abstract impressionist landscape. But at least I was confident that I had the dark-green corner assembly in the proper orientation because the artist’s initials are in the lower right-hand corner.

In the previous photo I didn’t know which direction the yellow assembly with the maple leaf should face. So being able to connect it with the two green ones was very satisfying, especially since my progress had greatly slowed down considerably after that quick start.

I focused on trying to grow my large assembly but it was very challenging. Jasen had included occasional segments of colour-line cutting.

Next I shifted gear and began working mainly on the light-coloured pieces (not including the white ones that I expected would be in the sky.) I clustered them all together on my board and was able to get most of them into one assembly, but unfortunately I could not yet connect it to my large “continent”.

Puzzle assembly often comes with bursts of progress. This next photo wasn’t really much later but it sure felt like a lot of progress at the time:

Then it was back to slow but satisfying progress. But as you might guess, with relatively few non-sky pieces left, and a growing collection of additional mini-assemblies which I haven’t been showing you in these photos, my pace of assembly gradually picked up.

Now there was nothing left to do but sky, but I still had a lot of puzzle assembly still ahead of me:

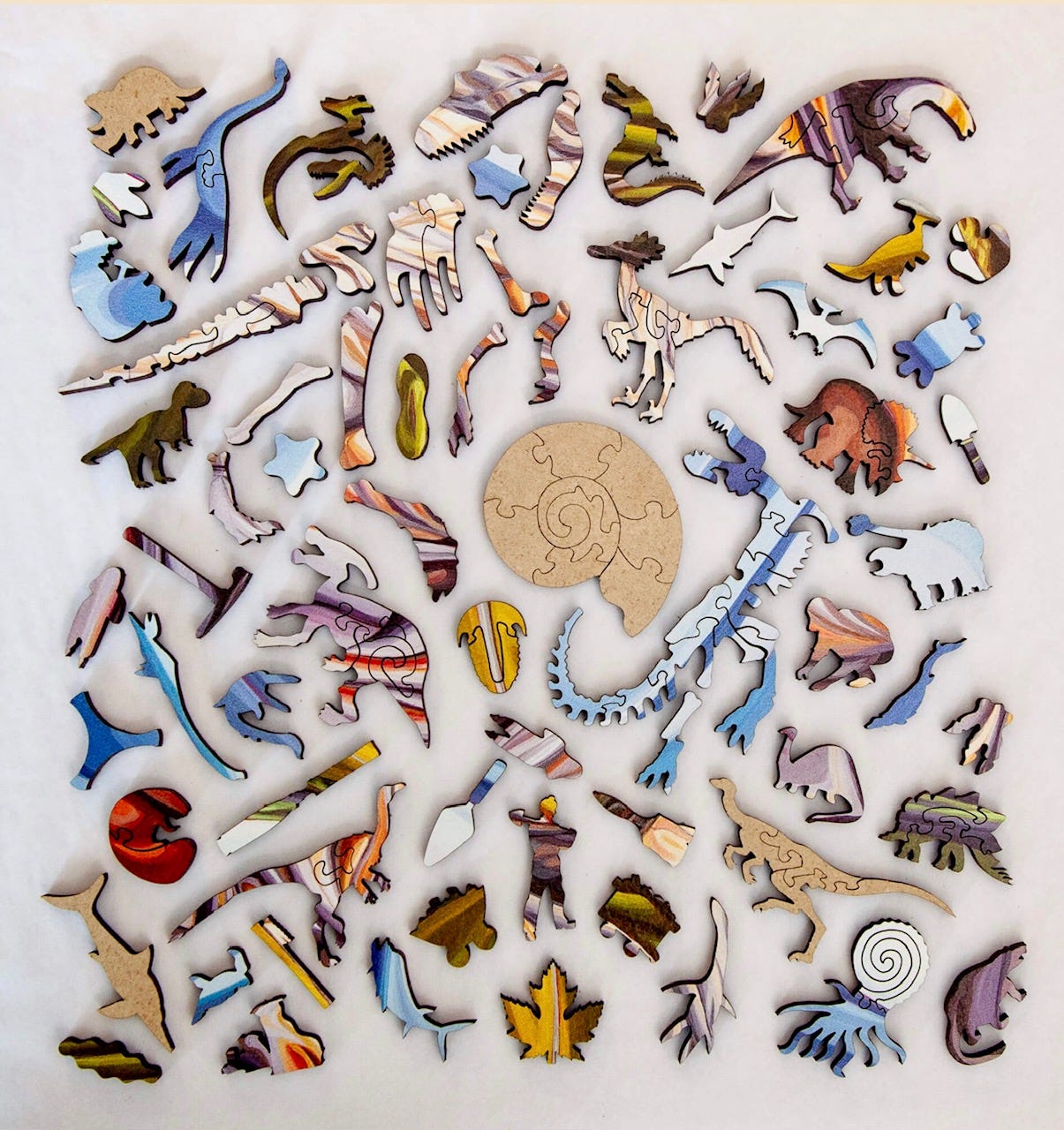

The above photo of the whimsies is from the StumpCraft website. The large multi-piece ammonite in the centre is not found that way in the puzzle. It is comprised of pieces from various places in it. This is a clever cutting feature that is sometimes called an alternate solution, but Jasen prefers to call them hidden whimwhams. You can learn more about the history of this kind of design feature from a digression near the beginning of this posting. Personally, I’m not really a fan of hidden whim-whams (alternate solutions) and got bored/frustrated before I found all of the pieces for this one.

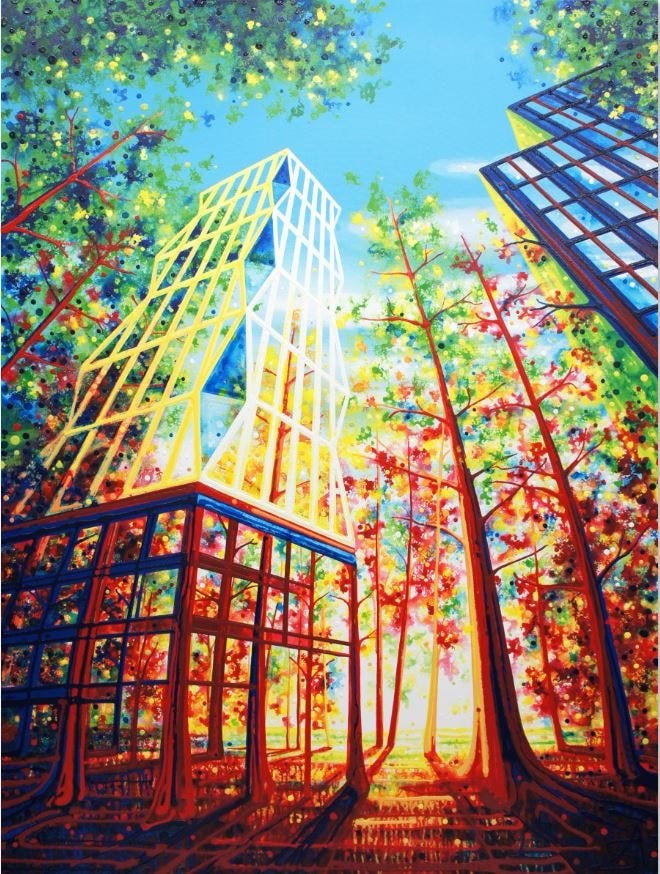

Urban Treehouse

The image for this puzzle is by Ontario-based “gravity artist” Amy Shackleton who describes her work as “painting with drips.” That describes a unique technique she has developed for making landscape paintings that depict structures from specific places in an imaginative spiritual relationship with a natural location somewhere else in the world.

Besides having a concept name, the titles of her paintings identify those places. In this case, the full name of the painting is Urban Treehouse (Kleinburg + New York). Kleinberg refers to an unincorporated district in Vaughn, Ontario north of Toronto that is known for its mature forests. I suspect that these are renditions of specific buildings but I don’t know where in New York they are located.

As she puts it on her website: “By integrating natural elements, such as trees, mountains, and bodies of water, with man-made structures, like skyscrapers, bridges, and highways, I invite viewers to contemplate the intricate ways in which the urban and natural worlds can coexist and interact.”

She explained her process in an interview for an art gallery blog in 2022 (lightly edited):

I started using drips back in 2008 [when she was completing her BFA honours degree from York University] to achieve natural/organic energy in my work. At that time, I used paintbrushes and tape to create the more concrete, architectural elements. I began to enjoy working with drips more than brushes and tape.

As I became more experienced with using gravity to direct the flow of paint, the paintbrush became an unnecessary touch-up tool. It was then I realized that with more planning, calculating, and layering I could eliminate the use of a paintbrush altogether. This became a challenge that took three years to master. In 2011 I created my first brushless painting. …

I use squeeze bottles filled with liquid acrylic paint to build each painting from the ground up with hundreds of lines and dots. The architectural aspects are highly controlled while the natural elements embody the spontaneous liquid impulse. I rotate my canvas to direct the flow of paint and use a level to help predict where each drip will fall. To create more organic effects, I use a water spritzer.

My style has evolved over the past 12 years. My early work was more loose and abstract since I was learning how to work with drips. Over the years, my work has become more controlled and representational. Now, I’m trying to loosen up a bit, haha. I want to find the perfect balance between spontaneity and control while combining nature with the city. My work wrestles with these opposing forces, just as my own optimism wrestles with reality.

Now, on to the puzzle assembly. I did not have much information about the image filed away in my memory banks (and of course I did the above research only after assembly was completed.) I remembered that it appeared to be make an artistic statement about the relationship between nature and architecture by conflating a forest with an urban high-rise building, but that was about it.

With 464 pieces, and rated a 4 out of 5 difficulty level by StumpCraft, I didn’t really need to add any further difficulty to this puzzle. But I did anyway, deciding to assemble it without using any side-boards for the pieces. That guaranteed that I would be tight for working space. I figured that I could make space as I went along if I did good colour sorting at the beginning.

Seeing the pieces sorted out I presumed that that the light blue pieces would be sky, and the dark colour-saturated blue-dominated and red-dominated pieces would be at the bottom of the image. That latter presumption was based both on my experience walking through dense forests as well as by my understanding of the aesthetics of composing a pleasing image.

I decided to begin with the sky . . .

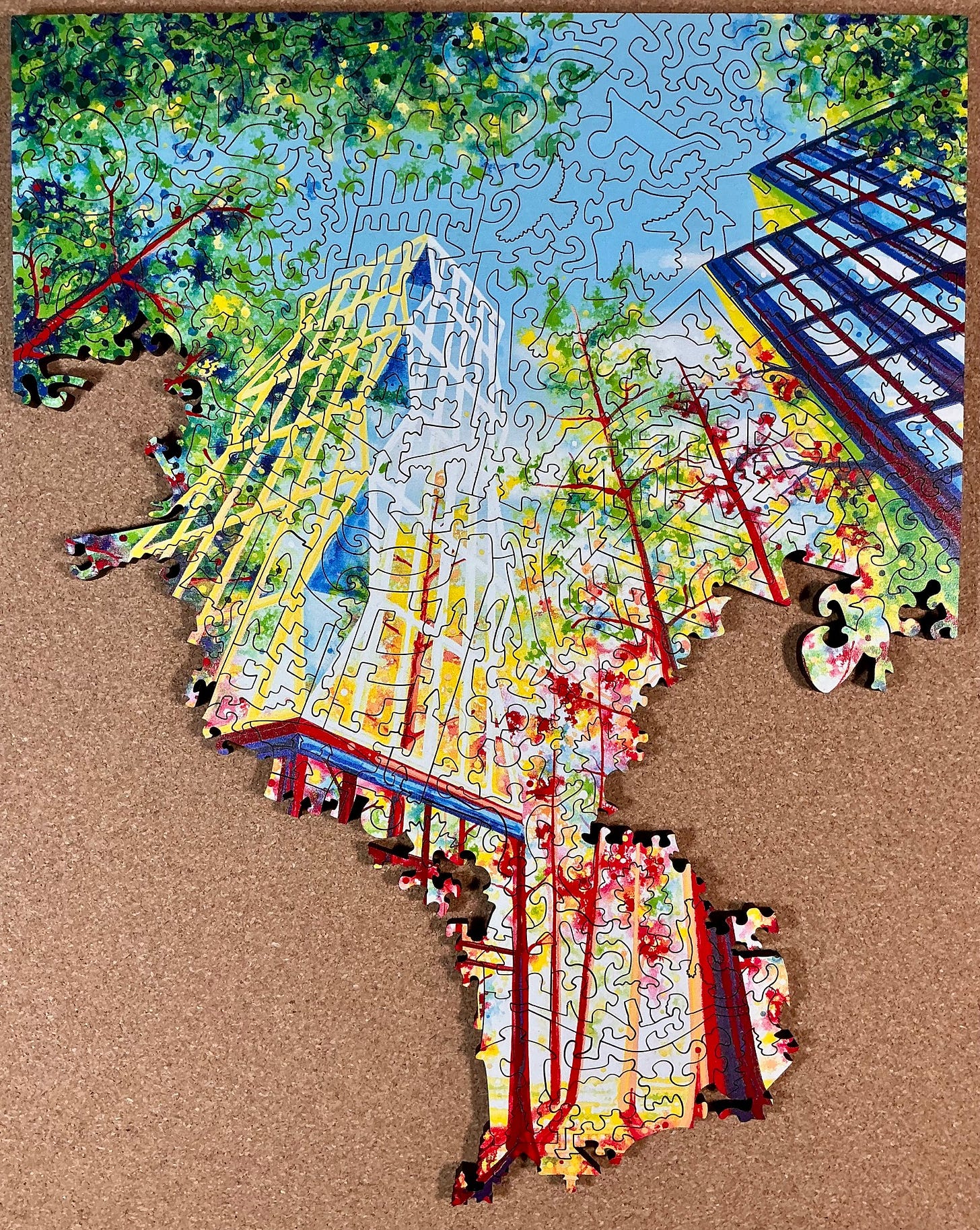

. . . then I built out from there using the straight red, yellow, white and red lines of the upper part of the high-rise. That did good job of beginning to give me some working space.

I had a lot of loose geometrically-cut pieces with red lines running through them. I have assembled enough of Jasen’s puzzles to know that one of his design tendencies is to have regions within the puzzle that have their own distinctive styles of cutting. Sometimes it can be that pieces have smaller than average with fiddly cutting and particularly small connectors but in this case it appeared that there would be a region with geometric cutting. So I moved the geometric pieces into the working space that have been vacated by sky pieces and began to work on them.

In general, I prefer cutting with curves and am leery of the ones that have straight-line cuts, which is why you may have noticed that I have not previously reported about any geometric-cut puzzles. My absence of practice with that style of cutting became apparent while assembling this part of the puzzle. I found it particularly difficult.

When I began feeling rather stuck on working on the frontier of that large assembly I began to consolidate the dark predominantly-blue and predominantly-red pieces on their respective lower corners of my assembly board. I noticed that there seemed to be a fairly high proportion of apparent edge pieces among the dark blue pieces. Before long I had my two bottom corners but I didn’t know which would be which.

I continued to work on building islands with the dark pieces, interspersing that task with making making progress in expanding my large upper assembly, with the red lines continuing to be helpful.

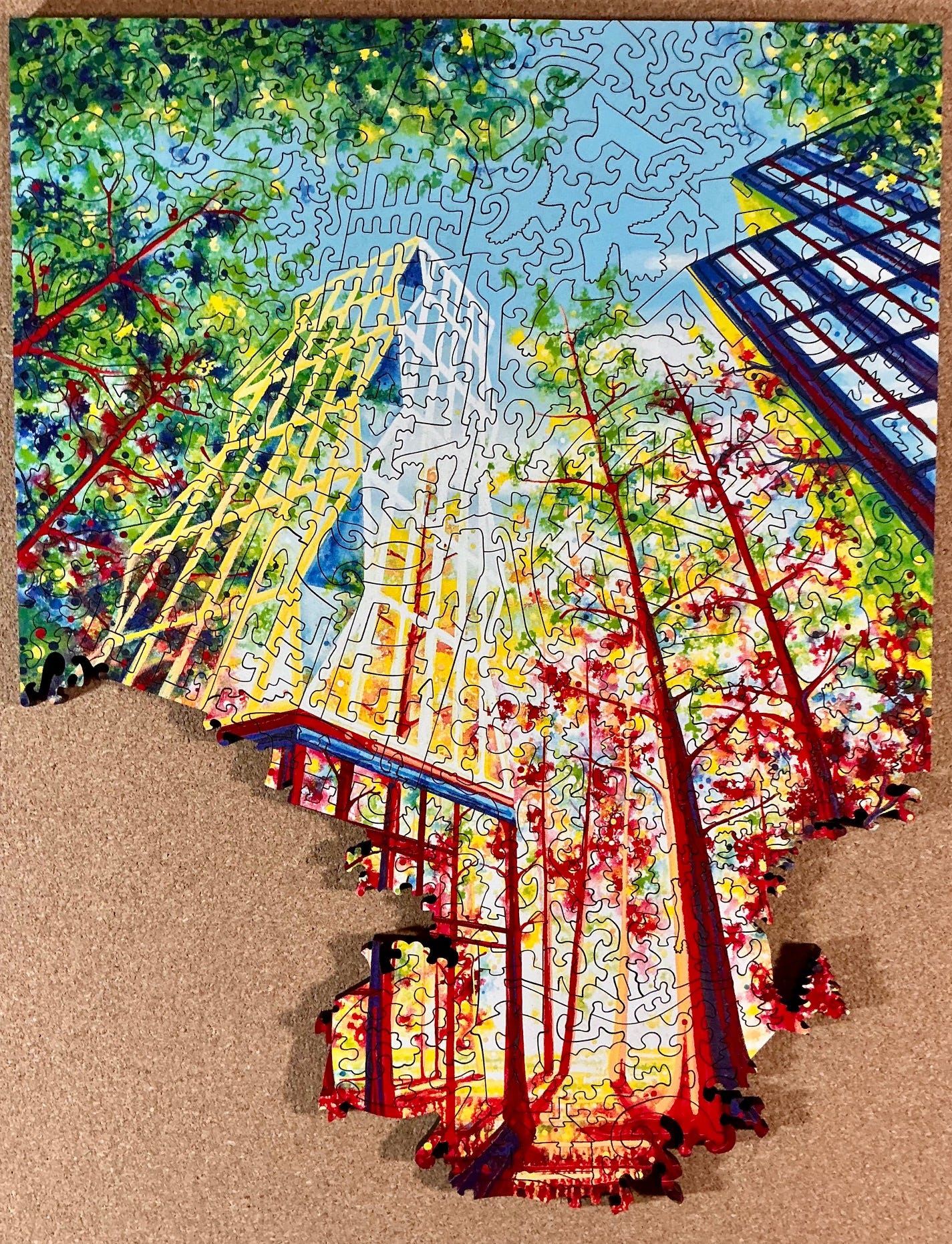

Then my progress had a growth spurt and I was able to integrate my dark-piece islands and many of the loose pieces into the larger assembly:

Then things slowed down again. My number of loose pieces was dwindling, but then so had the straight lines that had been helping me. This proved to be one of those puzzles that stays challenging right to the end.

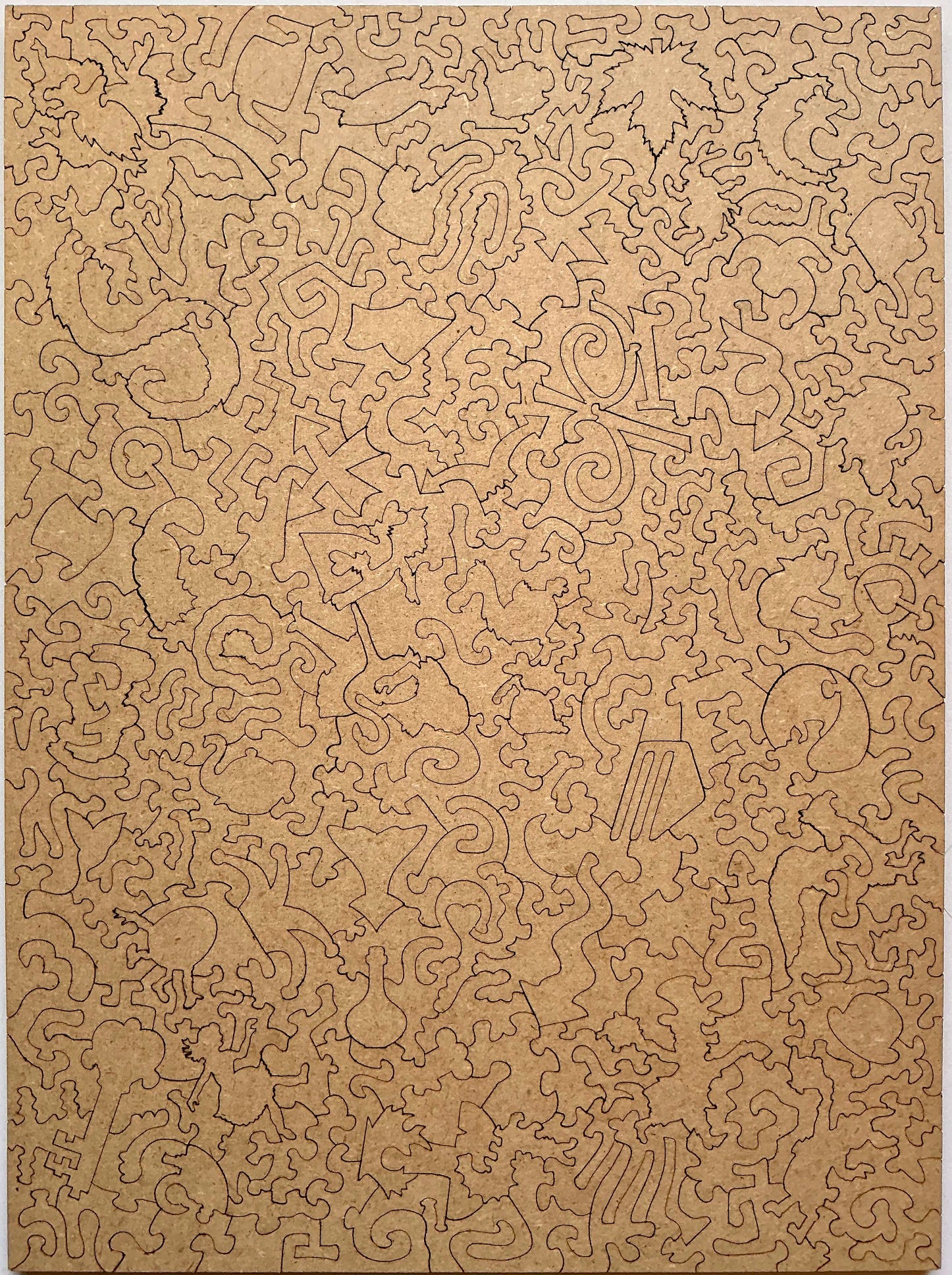

StumpCraft always rewards people who turn their puzzles over after completion to see what clever features they have missed during assembly. I find that I often miss relationships between what I had thought were separate figural pieces, or which combine to become bigger multi-piece whimsies than I had recognized. The backside of this puzzle retains the sense of balance and relationship between nature and artifact that is the core of the image’s concept. Note that a number of the small multi-piece figures relate to thoughts of home and organic growth. On the mid-right is a whimwham (multi-piece figural) of the Toronto city hall building.

The following three photos are from the StumpCraft website. Someone there (Jasen?) takes a lot of care in composing interesting ways to display their whimsies.

As usual, Jasen Robillard’s puzzle cutting design aims to complement and expand upon the meaning he finds in the image, and he explains his rationale in his puzzle notes in a Deep Dive essay about the puzzle. As with Amy, Jasen can be rather cerebral in his quest to create just the right overall cut and whimsies to suit the image. In this case he “initially set out to explore the various concepts of ‘home’.” But his design theme evolved as he worked on the project to incorporate both Amy’s thoughts on the duality of nature and architecture as well as perspectives that he found in a book by Dr. Iain McGilchrist about the differences between the brain’s left and right hemispheres, and how those differences have affected society, history, and culture.

As Jasen explains it:

The left hemisphere is detail and parts oriented, prefers mechanisms to living things and is inclined to self-interest. The right hemisphere (often associated with the arts) has greater openness and flexibility to suit the health of the whole. One quick way of summarizing the difference: the left sees the trees, leaves and branches; the right sees the forest as a complex ecosystem. [McGilchrist] argues that the modern Western world is overly and increasingly tilted towards the “straight and narrow” myopic perspective of the left-brain. He challenges us to rediscover and adopt right-brain modes of being to develop a more resilient, “both/and” integrated approach to living in the world.

Amy’s Urban Treehouse composition is perfectly aligned with these seemingly paradoxical modes of experiencing the world. Her geometric architectural shapes sprout up from the unpredictable, organic forest floor below. And yet even in the straight lines of skyscrapers, there exists an echo of the arched canopies and cathedral-like ceilings we inhabit when walking in the woods. The puzzle pieces intentionally echo the contrast of rectilinear, geometric shapes against the organic curves and chaos of nature.

Personally, I am not as philosophical as either Amy or Jasen. I definitely enjoyed the image’s bright colours, its simple-yet-complex radiant composition, and the creative dripping technique that produced it, but overall my general impression of this image remained stuck on its degree of conceptualization. Don’t get me wrong, I like it. But the image did not embed its way into my heart like some puzzles’ images do during assembly.

On the other hand, both Amy and Jasen’s deep thinking about this image, and integration of meaning in both the image and its cutting, may have worked on me at a subconscious level. My overall impression is that I will remember my assembly of this puzzle very fondly and that, like Badlands to the Bone, this is another one that I will definitely want to assemble again.

Tea from the Void

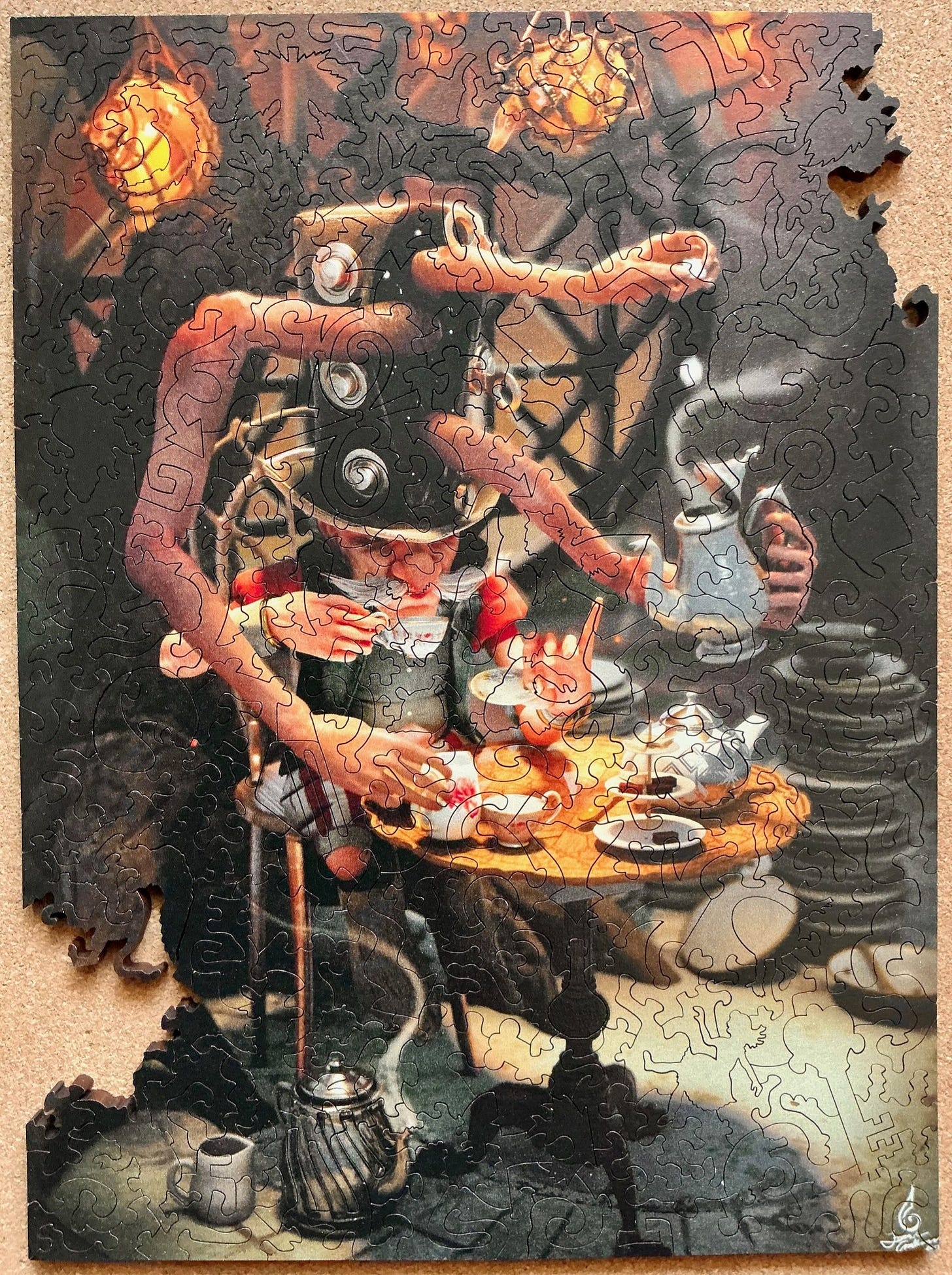

This is the only StumpCraft puzzle that I have bought used rather than new from the company. I had seen it many times on their website but the image never appealed to me mainly because it is too bizarre for my tastes.

The write-up on the website says that the character is the Mad Hatter from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland but I can’t see the relationship between what I see in this image and events in that story. For me, the image seemed too dark and creepy, what with all of those extra hands serving what I presume is a different never-ending solo tea party. But when I had the opportunity to buy a used copy of the puzzle I bought it anyway because I knew that Jasen’s cutting design would make assembly a fun experience.

The image is by Travis Anderson, a graduate of the Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver, where he specialized in animation, interactive technology, video graphics and special effects. He created this image in 2017, the year that he graduated from there. On his LinkedIn page Travis describes himself as a “concept artist.” I had to look that up. According to Wikipedia: “A concept artist is an individual who generates a visual design for an item, character, or area that does not yet exist. This includes, but is not limited to, film, animation, and more recently, video game production.”

Walt Disney began using the term in the 1930s to describe a role in his company’s animation process: It is done in parallel with initial story development but before storyboarding. Concept artists create the look and feel of the characters and their world. In this case, the subject of the image is not the never-ending tea party of Lewis Carroll’s story but seems to be a similar event from Travis’ imagination of the Hatter’s backstory.

While he was a student, as now, Travis worked both as a freelance designer and as a professional creative concept artist and 3D modeler for video games. I was not able to find any information online about why he created this portrait of the Hatter. It might have been a proposed illustration for a book, a character for use in a game design, or perhaps it was just a one-off project.

But I did find this. On his ArtStation portfolio page for this image Travis says:

The hatter was Mad not because of lead poisoning in the lining of his hat but because of the entrance to the void that it held inside. He kept it around because the horrifying aberrations inside just loved serving tea. You just have to try their chai. You'll simply lose your head over how good it is.

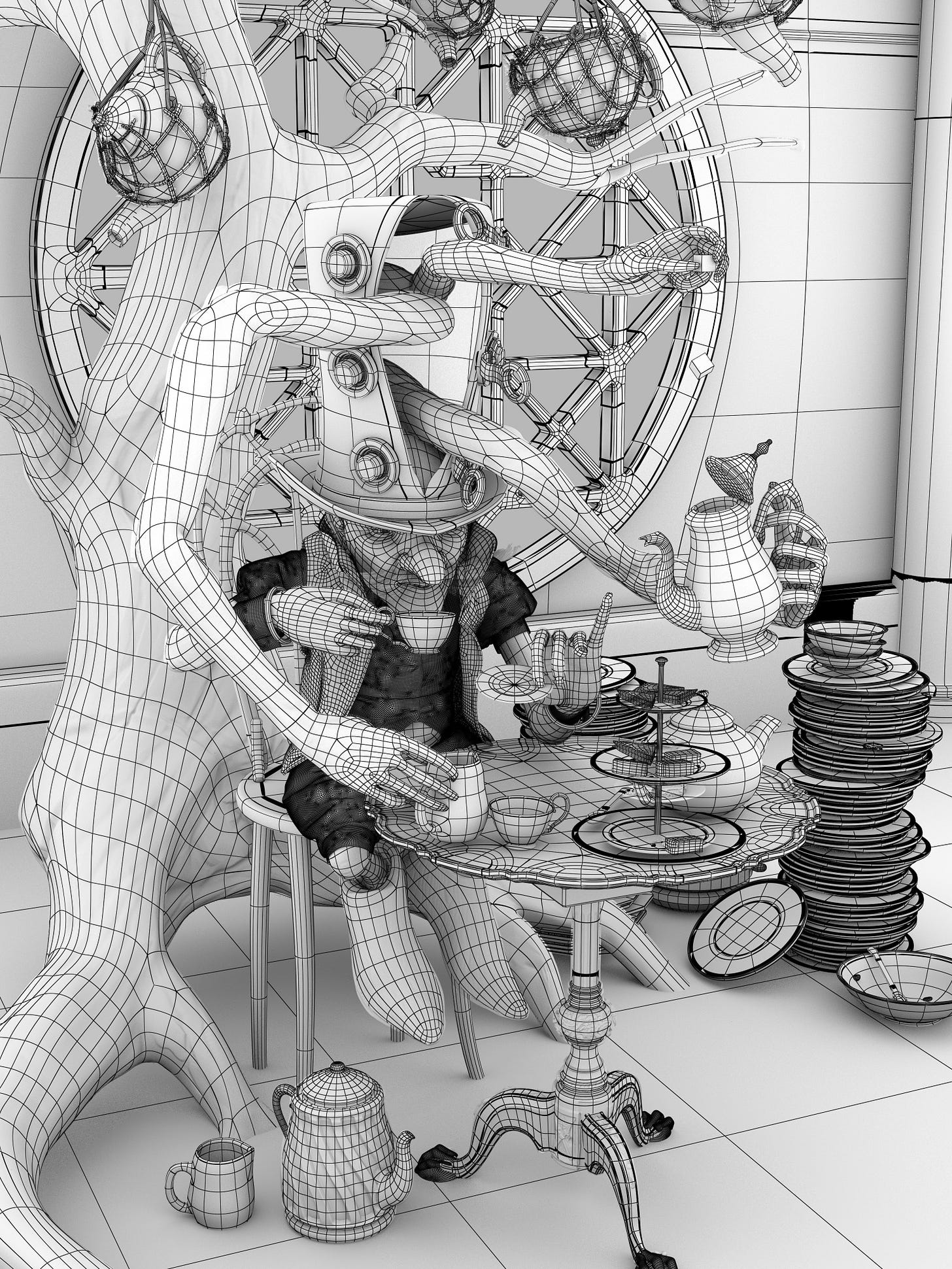

That site also includes two developmental drawings that clarify that the arms emerging from the hat, and the teapots that appear to be suspended above, all come from what appears to be a tree-like structure that is barely visible in the dark shadows of the finished image. That, I presume, is the Void, or the entrance to it:

Anderson’s cryptic explanation and those in-process images help me to understand the image a little better. I now know that it indeed is a totally different never-ending tea party from the one that Lewis Carroll imagined – a solo one catered by some sort of dark force. Usually, living with a developing image for several hours, studying it closely while assembling the puzzle, and understanding what it means lead me to appreciation of an artwork. But not in this case. The image of Tea from the Void still strikes me as creepy and dark.

On the other hand, Jasen Robillard’s cutting design fully lived up to my high expectations and that was enough for it to be another fun puzzle to assemble.

Since I bought this puzzle used, and I knew that it was one of StumpCraft’s early ones (issued in 2018, only one year after the company was launched), I should not have been surprised to discover when it arrived that it is in the company’s earlier pre-Covid style of packaging and labelling:

I have assembled two StumpCraft puzzles, Sunset Glow and Soft Maple in Autumn (reported here) that were released even earlier than Tea from the Void so I was not surprised that the cutting design for this puzzle has all of the creative quality that I have come to expect from Jasen Robillard’s cutting designs. But all of the StumpCrafts that I have bought and assembled were made no earlier than 2001.

When I first saw the box I expected that it might evidence the kinds of technical shortcomings like scorching that I often see from new puzzle-makers’ products. But as I flipped and sorted the pieces I found that was not the case. Not only is there no front discolourization from burning there isn’t even any scorching on the back side of this early StumpCraft product.

This puzzle only has about 250 pieces making it much smaller than either of the other two puzzles. But so many of them were dark that the relatively few lighter-coloured ones, and the artist’s signature, seemed like the logical place to begin:

Actually, it was the abundance of dark pieces on the image’s periphery that enabled me to begin to develop the image’s focus-of-attention quite early in the assembly process:

But after that, expansion of that image core grew fairly slowly. It never became frustrating but it certainly was quite challenging especially considering that it is a small 250 piece puzzle.

In my opinion, one of the design characteristics of great wooden puzzle is when all of the pieces, not just the figural ones, are interesting shapes in their own right. StumpCraft’s puzzles always achieve that, which is why they are considered to be one of the top wooden puzzle makers. Below are all of the loose pieces that remained at this stage. Aside from the fact that a high proportion are edge pieces, the variety and creativity of these dark non-whimsy pieces are typical of all of the pieces in the puzzle:

Jasen always creates very fine thematic figural pieces, and I especially appreciate that he usually does them as pure silhouettes without needing to burn in accent lines to make them recognizable. All of the whimsy pieces in this puzzle are thematic in that they relate to the Lewis Carroll story Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Here is a sampling of the more detailed ones:

Coming up:

Old-school puzzle-cutting: The story of Enid Stocken who was perhaps the finest British puzzle-cutter in the 1940s through ‘70s, and certainly one of the most prolific. Two descendants still cut puzzles professionally in her style.

Thanks for your Deep Dive Bill. I loved seeing your progress pics as well as reading your varied strategies in solving across the puzzles and within sections of a puzzle.

I'm still very much enjoying the exploration of the field of possibilities of puzzles as an art medium. As you attest, many of these explorations and stylistic tendencies show up in some of the earliest designs.

The quality of these Stump Craft puzzles seems to be apparent. The images used have a surreal character that isn't what I most favour, though I just mention that as feedback per my personal taste, not as criticism. As always, I do value your reporting, which you do with care and integrity. Thanks.

Moving on from my opening remarks, I will say that "Badlands to the Bone" is the one I would rate most highly of today's three puzzles. It is also true that the embedded fossils and paleontologists are impressive and pretty darn cool! I think I would also have liked to see a puzzle version of the hoodoos photo.

The image used for "Urban Treehouse" reminds me of reading about some actual skyscraper buildings in Singapore that are renowned vertical gardens structured to permit the extensive growing of vegetables and other greenery on numerous levels. Puzzle artist Amy Shackleton does seem to enjoy what she does!

Even though "Tea from the Void" is purportedly based on "Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland," the literary characters it brings to my mind are the Ents from Tolkien's tales of Middle Earth.

Thanks, again, for today's posting, Bill.