8. Decisions, Decisions – from Par Puzzles + Stumpcraft

Assembly and review of a laser-cut vintage-image puzzle, and essays about its artwork and artist and about the history of Par Puzzles (about 6200 words; 22 photos)

laser-cut Par Puzzles (US) and Stumpcraft (Canada)

artist – Stevan Dohanos (1944)

cut designer - Justin Madden

575 pieces 18” x 14” (47cm x 36cm) ¼” (6mm) mdf UV printed on wood

[Note: the photos are zoomable.]

This laser-cut puzzle is a delicious blending of the old and the new – a collaboration between PAR Puzzles, whose hand-cut products developed a reputation in the 1930s as being “the Rolls Royce of jigsaw puzzles”, and Stumpcraft of Calgary Alberta, a 5 year-old workshop that is developing a reputation for making among the very best laser-cut puzzles in our current era.

The puzzle is one of three limited edition collaborations that the companies jointly issued in Oct 2021, all based on old Saturday Evening Post covers. They are now on sale while supplies of last for 15-22% off their original price. It is not clear whether PAR will continue to release “L Series” laser-cut puzzles since neither Par nor Stumpcraft have announced any further such collaborations. This 575 piece puzzle’s sale price is $179 CAN ($140 USD).

[Update: The limited release collaboration puzzles are now sold out. Par Puzzles is now cutting its own puzzles based on Justin Madden’s cutting designs.]

Assembling Decisions, Decisions led me into research rabbit-holes regarding both the background of the artist and image and of Par Puzzles. The latter is a fascinating story of a gay couple who during the Great Depression turned puzzle-making into a very prosperous forty year career at the centre of New York’s cultural and Broadway scene, enabling them to live and work in a mid-town Manhattan 2-storey penthouse. There is a two-part essay about the company’s history after my puzzle review.

The painting and artist

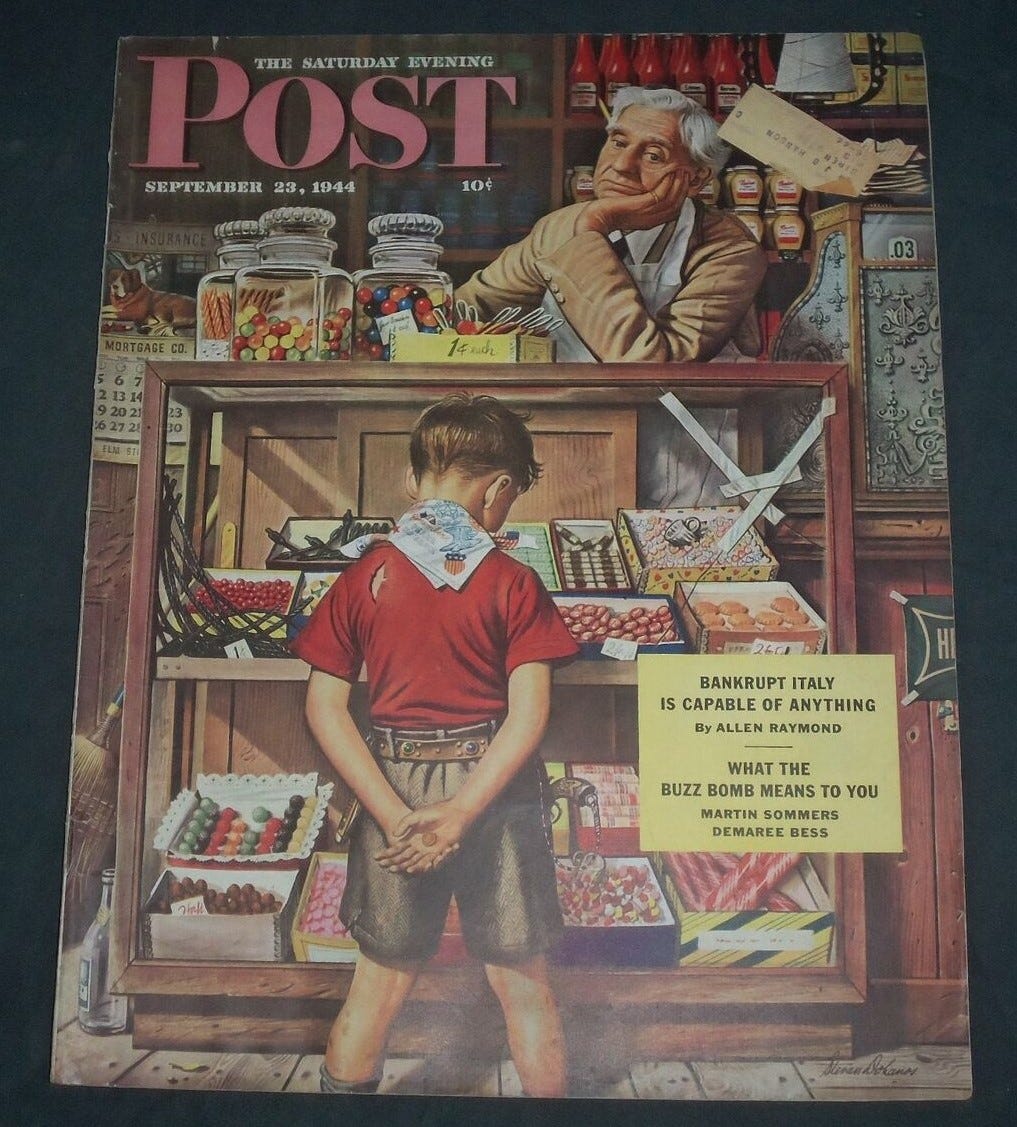

The Saturday Evening Post is America’s oldest magazine. It was initially published in Philadelphia in 1821 out of the same print shop that Ben Franklin bought in 1729 for his Pennsylvania Gazette.

The Saturday Evening Post’s heyday was from the 1920s to ‘60s when it was America’s most widely circulated magazine and had adopted a distinctive style of cover illustration depicting thoughtful, nostalgic scenes of everyday life. Many were painted in what came to be called the American realist style (a subset of genre painting) of which this image is a perfect example. Each cover illustration told a story. Norman Rockwell was the magazine’s most famous cover artist. His paintings graced 322 of its covers over a 47 year span that began in 1916, but there were others. This painting is by Stevan Dohanos (1907-1994) who painted 125 covers for the magazine.

Devanos was born in the mill town of Lorain, Ohio in 1907, the son of Hungarian immigrants. From an early age he had to work to financially assist his family, and he left school as early as he could at the age of 16. According to his online bio on the Illustration History website:

He worked his way into a white-collar job in the steel mill office, and spent his free time copying the pictures on the calendars that hung on the walls. Before long, co-workers were offering to buy his drawings. He charged fifty cents apiece, then a dollar, and eventually a dollar fifty for a copy of a Norman Rockwell Post cover.

Inspired by this he decided to get art training, first from a correspondence course and then by enrolling at the Cleveland Art School. In 1935 he was offered a job doing illustrations in New York, and the next year he enlisted for a Works Project Administration job painting a mural in the Virgin Islands. While there he continued to develop his technique by making and selling paintings on side.

The resultant Virgin Island paintings proved popular, and three of them were bought by Eleanor Roosevelt. His reputation and career were blossoming. When he returned to New York his paintings were in high demand for both illustrations and advertising but he also continued to take on WPA mural projects. His goal – his dream job – was to get a salaried job creating covers and other artwork for The Saturday Evening Post, working in the company of Norman Rockwell and the other great genre painting artists of the day. In 1943 he got the gig.

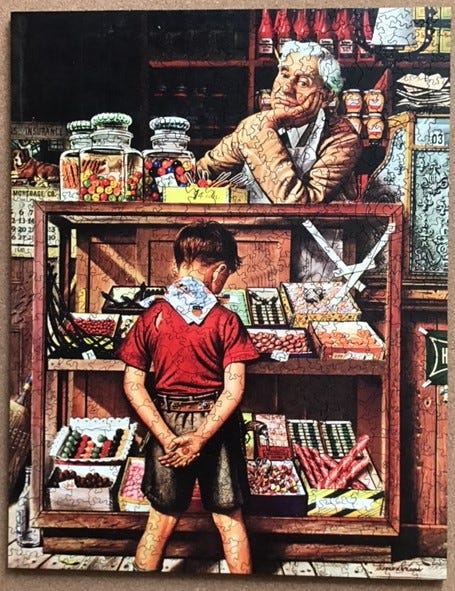

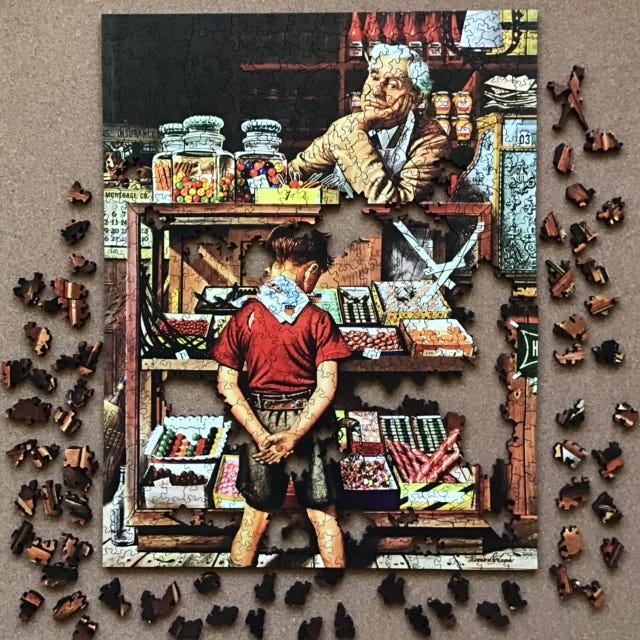

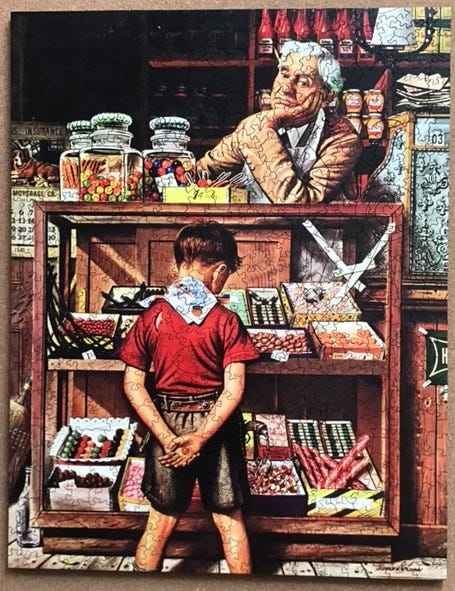

This puzzle’s image is from the Sept 23, 1944 cover of The Saturday Evening Post.

The painting is from four years before I was born but that boy could well be me. I know how he feels. When I started elementary school, every three weeks my mother would give me a quarter to go to our neighbourhood barber shop to get a haircut “so I would look presentable.” She also gave me nickel to spend at the adjacent drug store. Oh how I agonized over how best to spend my nickel! Should I get a chocolate candy bar, or a small pop from the soda fountain, or buy a whole variety of penny candies? Decisions, decisions.

The Par and Stumpcraft websites describe the story of this image as:

We've all faced the challenge and paradox of choice: we love having endless variants and options, yet too many can lead to a sense of overwhelm. In addition when given too many options, we're left with a lingering doubt as to whether we made the right or optimal choice in the first place. What if I'd chosen the red jujubes instead?

. . . In Decisions, Decisions (originally published as "Penny Candy"), we see Dohanos' humorous and insightful juxtaposition of two generations. The old man seems to be reminiscing about life; perhaps mulling over his business decisions or reflecting on path well-traveled. In contrast, the young boy has sweets and the immediacy of here and now on his mind. A penny for either of their thoughts to be revealed!

In 1948, Stevan Dehanos along with Norman Rockwell became founding faculty members of Albert Dorne’s Famous Artists School, a correspondence school for aspiring artists. (If you're thinking of matchbook covers or comic book pages with a cute little clown, pirate, or pooch drawing above the words "Draw Me," you've got the wrong school. That was Minnesota's Art Instruction School. Famous Artist School advertised in classier venues such as TV Guide and Look magazines.) Students in the program included such celebrities such as Tony Curtis (who later gained recognition for his easel paintings), Charlton Heston, Pat Boone, and Dinah Shore.

In later years Dohanos became interested in US postage stamp illustrations. He was the designer of 30 of them and became design coordinator for the Citizen Stamp Advisory Committee. The Post Office’s own stamp museum and archives is named after him. Perhaps more meaningful, his childhood hometown named the elementary school in the working class neighbourhood where he grew up after him.

For more information about Stevan Dohanos I recommend this online biography, this article, or his NY Times obituary.

First impressions

I have received four previous orders from Stumpcraft. I was expecting this puzzle’s box to look like the ones I was familiar with from that company, but it is a variation of the glossy black box that Par has been using since the 1930s.

One concession to this being a collaboration is that it has a small thumbnail image on one end of the box. I don’t use such images for assembly, but I do find them handy when looking through my storage. For people who want a larger high-resolution image for assistance Stumpcraft has a printable one available online

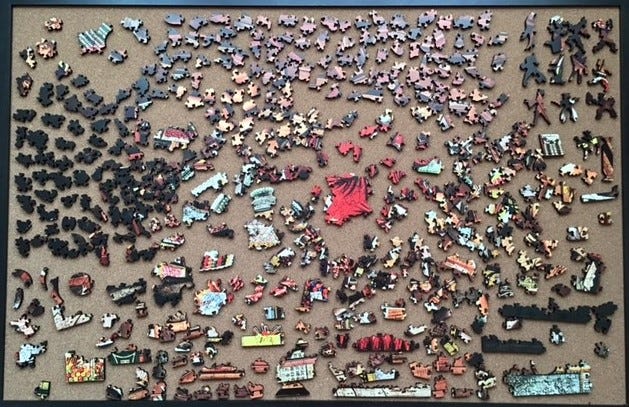

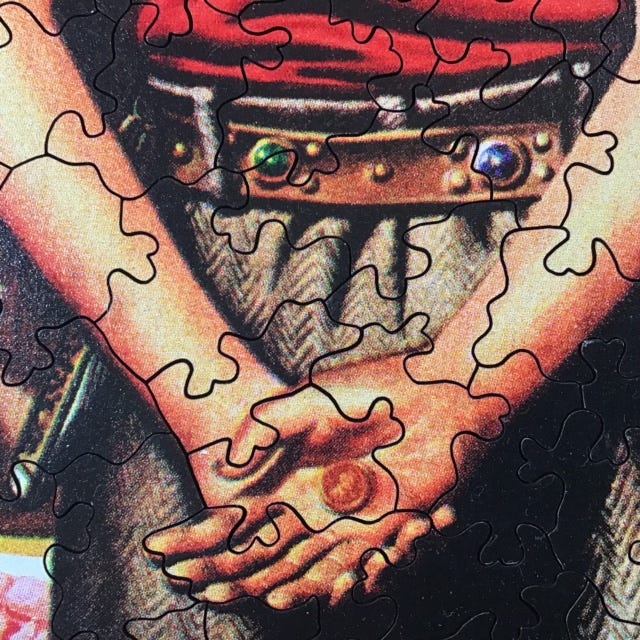

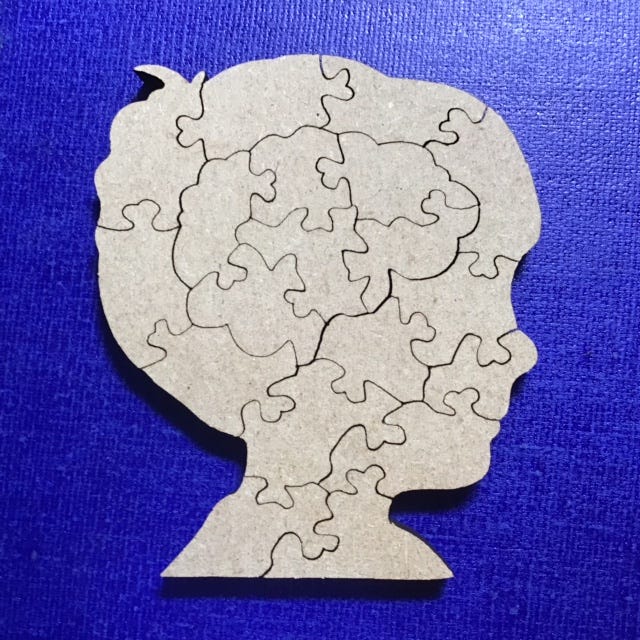

Pouring the pieces out (carefully) yielded the familiar campfire smell, but not as strong as I remember from previous Stumpcrafts. My attention was immediately drawn to the very engaging and stylish whimsies - oops, sorry, silhouettes - that is what Par traditionally calls such pieces. There were 12 of them. I later discovered that the puzzle also includes 10 multi-piece figurals, including a large one that I didn’t discover until it was already assembled.

The puzzle is mostly interlocking and most of the connector knobs are the earlet style (using Bob Armstrong’s classification system.) I was pleased to find that, for the most part, the cutting is fluid and flowing, not angular.

The pieces are Stumpcraft’s standard ¼ inch (6mm) medium density fibreboard which is very resistant to chipping (but one piece does have a small, inconsequential chip only visible from the back.) The image is Stumpcraft’s usual UV printing directly onto the mdf which produces rich colours. Of the 31 wood puzzles that I have assembled so far Stumpcraft always has the best, most vibrant printing.

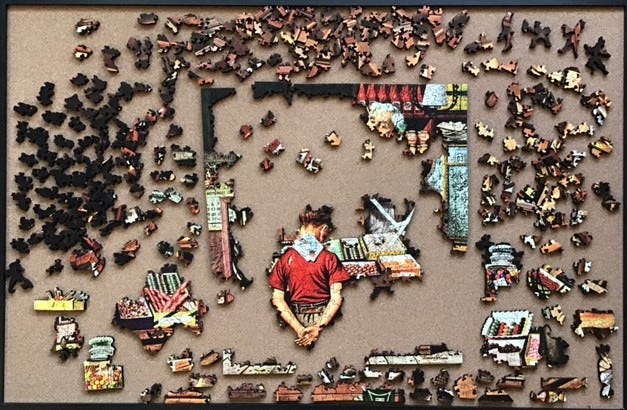

Since my recollection of the image was only a vague memory I was somewhat surprised at how many dark pieces there were. I began to wonder whether choosing this particular 575 piece puzzle was a good choice for a summertime build. I also wondered whether I had made a good choice to sort all of the pieces onto my large 2’ x 3’ (60 x 90 cm) puzzle board rather than also use my smaller board for some of them. Would I be able to make myself enough working space?

Assembly and review

As usual, I began with targets of opportunity – distinctive colours or shapes. There were enough apparent edge pieces that gave me some linear clusters, and many of the red pieces also came together easily. I correctly remembered they were the boy’s shirt. I expected that the old man’s face would be easy too, but it wasn’t (because the same colouring and wrinkles were found in his jacket.)

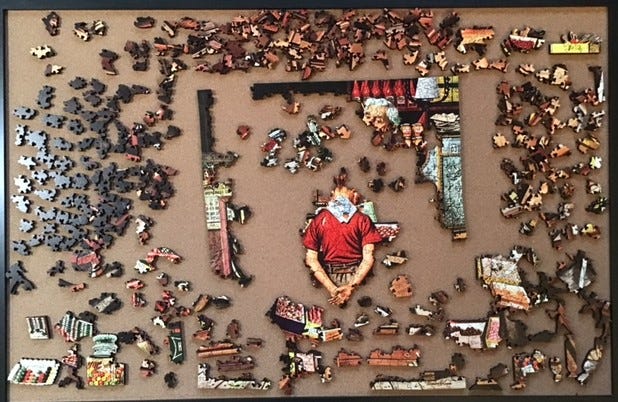

The various types of candies on display each had their own distinctive textures and colours, and I began accumulating a number of candy clusters . . .

. . . and the display began to take shape. The little hints of adjoining colours on the edges of pieces helped.

I had had my eye on this particular puzzle as being my favourite image of the three Par+Stumpcraft collaborations ever since they were full price. But even when the price was reduced I was somewhat hesitant about buying it because it still cost $20 more than Stumpcraft’s other puzzles in this size range. I already knew that I love the challenge and creativity of Jasen Robillard’s cutting designs, and designs by Par’s Justin Madden were an unknown quantity. The idea of Stumpcraft without Jasen’s design seemed like a risk.

I only bought it when I realized that this was a limited edition, that the sale was “while quantities last”, and that this might be my only change to ever experience a Par design (see the 2 part essay below about that company and its illustrious history.) I decided to assemble it as soon as it arrived even though it seemed more like a wintertime than summertime puzzle. This was partly so that I could review it for you in this newsletter-blog while it was still available, and partly to see whether I liked it enough to get another of the collaboration puzzles while it was still available.

It was at about this point in the puzzle that I ordered both of the other Par+Stumpcraft puzzles. I wanted to make sure I got my order in before they were sold out.

By now I knew that (unlike at least one of the other collaboration puzzles) this one was rectangular and did not appear to have any irregular edges, although it does have a lot of line cutting which creates some false edge pieces. In addition to continuing to work on the candy display I decided to focus on the edges. I only figured out later that Justin Maddon’s cutting design seems to use short little colour-line cuts on the edge pieces to make the puzzle’s perimeter tricky to piece together.

I began to also focus on the yellow pieces (that turned out to be the old man’s sleeves) and the many black ones.

Basically, at this point I had only two types of pieces left now – woodgrain and black. (And, of course, my recurring nightmare that there must be one or more pieces missing from the puzzle. By now, my brain keeps reassuring me that this is highly unlikely, but my ego says that if that if they were all there I would already have found the ones needed to fill some very obvious places.)

Wow! What a great puzzle!

Perhaps it is just that I am a nostalgic old codger but I am really fond of this image. And the puzzle design itself was as enjoyable as I have come to expect from Jasen’s Stumpcraft designs. (That is high praise indeed!)

My only complaint is more of a quibble. This artwork is licensed from Curtis publishing (who own the rights to The Saturday Evening Post’s artwork) and the image is from a print of the painting, not from the original painting itself. Also, the puzzle size is much larger than the magazine cover that the picture came from. Some colours in the image show obvious graininess due to technical limitations in 1940s-vintage offset printing.

Perhaps this was an artistic choice to highlight the vintage nature of the puzzle’s artwork and its magazine cover roots, or Par Puzzle’s long history of using artwork that had been printed with such technology. But puzzle assembly draws one’s attention to fine details such as this and for a while I found the graininess disconcerting. I think I would have preferred it if the image had come from the original painting. Stumpcraft’s modern high-resolution UV printer would have really made this charming image pop!

PAR Picture Puzzles - Part 1

PAR Picture Puzzles (as it was then known) has a very interesting origin story. The brand’s success is especially remarkable because they were established in 1932. (To save you from having to do the math, that is 90 years ago.) In that year Great Depression unemployment was approaching 25% and many talented but unemployed craftspeople were starting independent wooden puzzle companies. It was also the year when many inexpensive die-cut cardboard puzzles suddenly became available. In America, today only Par remains from that time period (and as far as I know, there is only one other puzzle company in the world that survives from that era – the Stocken Family’s Puzzleplex, in England.)

Par was founded by Frank Ware (1903-1984) and John Henriques (1903-1972), a young gay couple who lived in Manhattan. Like many creative people during those lean years they were motivated to take up puzzle-making by having lost their jobs. At the time, America was in the midst of a huge jigsaw puzzle craze and (rather like during our era’s Covid pandemic) the established puzzle-makers couldn’t meet the demand. Hundreds of similar home workshop puzzle businesses were established to take advantage of this opportunity.

[Note: I discussed that puzzle craze in my long introduction to this post about two puzzles from that era, but my primary focus in that essay was on the boom in Britain. For more about the American “Golden Age” of jigsaw puzzles see this brief history article by Anne D. Williams, the definitive historian on the topic. In this post I discuss how two young creatives from our time were attracted to puzzle-making by the Covid pandemic’s similar sudden upsurge in demand.]

John Henriquez was a long-time jigsaw-puzzle buff and very fast assembler, who proved also to be very fast at saw-work and capable of very intricate, precise cutting. I presume that he would have been the one primarily responsible for developing their characteristic tricky puzzle designs. Not only did he and Frank draw from the best existing cutting tricks but they also invented new ones, like drop-outs (i.e., leaving sneaky empty spaces within the puzzle, making assembly much more difficult.)

Frank Ware also became an adept cutter, but his main contributions were as the artist (he designed their silhouettes, which is what they called figurals or whimsies) and he had impressive marketing savvy. They were both hard workers, dedicated to the vision, and very good at schmoozing with the rich and famous in the Big Apple’s art, literary and theatrical scenes, and cultivating clients from that city’s social elite.

The couple had begun puzzle-cutting in 1931 more as a hobby than an intended profession. Believing that the financial turmoil would soon pass they began to pass their time of enforced leisure by making puzzles to be gifts for friends and family. They became obsessed with making the very finest puzzles they could; ones that far surpassed those that were commercially available.

As the Great Depression settled in as a long-term reality they decided to make their hobby a small business, but still, more as a way to keep busy during what was expected to be temporary unemployment. A later Par brochure described it this way:

The aim was simply a better puzzle … not for profit. The makers were both puzzle fans of many years standing. They knew the relative merits of the good puzzles on the market. And they knew, too, that certain definite improvements and refinements in materials, in workmanship were possible. They experimented for months – with pictures printed on different papers – trying many woods and styles of cutting – testing saw blades and glues. They developed rigid specifications. Then they made puzzles that set a new standard.

When they decided to make puzzles professionally they adopted a very unconventional and counterintuitive business plan. Instead of aiming for the booming middle-class market they decided to sell their puzzles as prestigious, one-of-a-kind works of art in themselves. Customers would be able to buy or rent ready-made ones, or order them with customized cutting that included their names, monograms or other personalized touches.

Ware and Henriquez did not try to make their puzzles affordable for the middle class: They sold or rented them at such high ultra-premium prices that only the very wealthy could afford them. Their very high prices brought them more, not fewer, customers! (I learned about this phenomenon in my micro-economics class at university. Usually, raising prices lowers demand. But some select items (like diamonds, Apple’s MacBook Pro, and some private club memberships) develop a premium value just from being so expensive and exclusive. Economists call this effect a prestige pricing. It really works, but only for a very few select products, and it can be difficult to maintain.)

Perhaps most surprising, the customers only rarely knew what the image on a Par Picture Puzzle would be when they commissioned it (unless they had chosen the artwork in advance) – they had to trust Ware and Henriquez’ good taste, and/or their ability to read clients’ personalities and anticipate their desires. And even when customers got their new or rented puzzle it came in a plain black box with no guide picture. Even its title was often misleading, for example, “Bobby’s Beat” was a London street scene and “Mad Meadows” was the 1939 World’s Fair (held in Flushing Meadows New York.)

It was Frank, who had been an advertising executive before the Wall Street Crash who came up with the idea for this very bold business plan. They were in a sufficiently good financial situation themselves that they didn’t need to immediately rush into commercial production. They spent a year fine-tuning and improving every aspect of puzzle-making to ensure that they were indeed making the very highest quality and trickiest puzzles available, and fabricating them with sufficient panache that their quality was readily apparent.

In 1932 the “Jigsaw Jag” craze was still in ascendency, but other makers were focusing on lowering their production costs to survive what was becoming cutthroat completion. But Par wasn’t in that game. Their target market was Manhattan’s ultra-rich for whom price was no object when it came to getting the finest quality, most prestigious puzzles available.

Ware accompanied their launch with a conventional advertising campaign in publications like the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and The New Yorker. But their most effective marketing was a well-placed window display in midtown Manhattan, and especially, word-of-mouth from their prosperous friends and clients to their puzzling friends around the world.

The enterprise was an immediate success and the business grew quickly, especially when they began to emulate other home-workshop puzzle makers by renting puzzles as well as selling custom-made ones (but still at an ultra-premium price.) By 1936 they were able to move from their West 154th Street walk-up apartment and basement workshop to a two story penthouse on 53rd Street, between Madison and Fifth Avenue, in the heart of the City’s cultural and entertainment district.

Besides these expensive new digs being every New York culture-lover’s dream accommodation, the move was, I suppose, also at least partly justified by business logic. This new location meant more time could be spent on puzzle-making and marketing since less travel time was needed to access events at the theatres, museums and art galleries that they loved and where the made and maintained their social contacts.

They no longer needed to do any advertising but they did need to maintain their status as bon vivants among Manhattan’s cultural and social elites. Some of their closest friends were Broadway producers and with their increasing prosperity the couple became recognized as significant angel investors in proposed Broadway musicals. They astutely picked smash hits including The Music Man, Mame, Fiddler on the Roof, and just about everything that Bob Fosse directed and choreographed.

The couple seem to have become local New York celebrities in their own right, which added to their opportunities to mingle with the rich and famous and attract new customers. But more importantly, even when their new friends could not be persuaded to become puzzle-people themselves they spread the word to their own wealthy puzzle-hungry friends around the world.

According to Anne Williams’ research, people who knew the couple described them as “eccentric” and even “zany.” They were witty, irreverent, outrageous, and sometimes even rude. Ware and Henriques did not conceal their sexual orientation, but in keeping with the times (when homosexuality was illegal) they did not flaunt it and in public they were discrete and proper. On the whole, people found them outgoing, amusing and interesting, and they made many close friends among the City’s cultural elite.

Industrialist customers saw the potential for them to increase profits based on the fame that the Par brand had gained and made suggestions for expansion and growth. But the couple loved their lifestyle in New York’s cultural hub and the size of their company remained limited by the size of their midtown Manhattan penthouse apartment/workshop. They stayed with that home workshop format for 40 years, continuing to raise their quality standards (and their prices) and the exclusivity of their creative handmade puzzles along the way.

Over time, the 1930s “Jigsaw Jag” faded away, being replaced by other forms of entertainment (including television), but nothing could replace the feeling of opulence that assembling a Par puzzle gave to those who could afford the luxury. Indeed they even became an icon for extreme wealth.

When the movie Citizen Kane was released in 1941 everyone (including people who had never actually seen one) knew that the thick-pieced puzzle that Susan is assembling in their lonely palatial mansion near the end of the film must be a Par.

Even when Par used the same fine art print or poster as its image no two puzzles were ever the same. Ware and Henriquez achieved their goal of getting handmade jigsaw puzzles accepted as being capable of being thought of as timeless works of art, and they were the unchallenged masters of their craft. Even now, Par puzzles from that era rarely become available for sale. The truly are thought of as being priceless family heirlooms. And when they do come up for auction or sale they command extraordinarily high prices.

In the ‘30s. John and Frank had been the only ones who did the actual cutting and the ever-growing task of correspondence with customers. They did hire helpers for other tasks like materials preparation, packing, shipping, delivery, and cleaning. In the ‘40s they began to take on apprentices to learn the high-skill tasks, and some of those apprentices were able to perform them to the couple’s demanding standards.

One of those assistants was Arthur Gallagher (1922-1989.) He began working for them in the late 1930s teenager as a messenger, and after military service in WWII he returned to become an apprentice. He increasingly progressed to the point where he became a master cutter.

In 1972, John Henriquez passed away and Frank Ware lost all heart to continue puzzle-making without the companionship of his life- and business-partner of more than 45 years. In 1974 he gave the entire business – saws and other equipment, materials, designs (including his catalog of silhouettes), art prints and posters, and the invaluable client list – to this long-time colleague Arthur Gallagher, and John Ware retired from puzzle-making.

For more information about Par Puzzles during the Ware/Henriquez era I recommend this 2002 article by Anne D. Williams. It includes many more details that I have not included here, including the names of many of the famous celebrities and ritzy families who were their loyal customers.

Par Puzzles – Part 2

The things that John Ware could not pass along to Gallagher were his own considerable artistic ability and business acumen, and more importantly, the couple’s ability to socialize at par (pun intended) with people in high society. But he had passed along the commitment to the concept of making puzzles of unmatched quality, and the knowledge and skills needed to maintain that standard.

Arthur Gallagher relocated the business closer to his home on Long Island but operated on a reduced scale. He continued to operate under the same successful business model that he had been given, but he lacked his predecessors’ social and marketing flair. His son gave puzzle-making a try but decided not to continue in the demanding role. Gallagher took on other apprentices. One of them was John Madden, who learned puzzle-making from him part-time while continuing his full-time job as a wallpaper-hanger.

In the early 1980s poor health forced Gallagher to retire, and he passed ownership of the company and its assets, as well as the art and secrets of making Par Puzzles, along to Madden. But Madden had a wife and two children to support and was not ready to abandon his job as a skilled wallpaper-hanger to the uncertainties of a puzzle-making business, even if that business had the cachet of the Par brand name. He continued Par Puzzles, but on a part-time basis.

Like Gallagher before him, John Madden maintained the company’s high quality standards but didn’t have the reputation for creativity, social contacts or flair that Ware and Henriquez had. But he did have Henriquez’ file of very-imaginative and intricate silhouettes and the skill to cut them, and Par’s client list that still had some loyal customers.

But now Par faced competition in the elite puzzle market from a new challenger. Stave Wooden Jigsaw Puzzles had been founded in 1974, the same year that Frank Ware retired, and Steve Richardson was a very talented cutter and designer who did have a flair for marketing. He adopted and expanded upon Par’s business model to perfection.

As with Par’s original owners, Richardson was motivated to get into the puzzle business my having been laid off and he was self-taught. But he had the model of Ware and Henriquez’ more than forty years of success selling extremely fine puzzles for extremely high prices, and unlike the Par’s successor owners, he had the creativity to make many design innovations (e.g., he was apparently the first puzzle-maker to commission original artwork and turn the process of image-making and cutting design into an interdisciplinary collaboration.)

Over time, Stave attracted the rich and famous to that brand and assumed both the titles of “Rolls Royce of wooden jigsaw puzzles” (Smithsonian Magazine, 1990) and “World’s best jigsaw puzzles” (Forbes, 2011), as well as the ability to charge much more for its products than any other jigsaw puzzle maker. For more information about the rise of Stave Puzzles I recommend reading this 2011 article from Forbes Magazine.

As a part-time side-gig, John Madden produced about 12 Par custom-made puzzles a year. Then another layoff led to a Par revival. During the 2008 recession John’s 26 year-old son Justin, who had not initially intended to be a puzzle-maker, got laid off from his job as a bond trader in Los Angeles. Like so many before him, he decided to give puzzle-cutting a try. He installed a scroll saw in his studio apartment (putting a tarp over his bed to protect it from sawdust) and with telephoned advice from his father back in New York he began making puzzles as gifts for friends to see if he had a knack for it. He did.

In 2010 he moved back to New York and for the first time since the Ware/Henriquez era, Par was a family business again. Par was still at a much reduced scale, with few orders for custom puzzles, and Justin’s apprenticeship was just beginning. Over the next year he had a better opportunity to learn from his father in-person and he cut a 300 piece puzzle himself every day. He is quoted in a New York Times article: “I was pushing the envelope on each of the designs and the creative aspects of the business.”

Working together with his father, who had retired from wallpaper-hanging, they had increased PAR’s output of custom-designed puzzles up to about 80 puzzles a year before the application of Covid pandemic’s safety precautions had many people in home isolation.

There were a few months in the early Covid days when jigsaw puzzles became as hard to get as toilet paper. Inquiries to Par came flooding in but most people were scared off by the high prices. Even so, a surge of orders for custom puzzles came in. In June 2020 Justin described their chaotic April and May for a NY Times reporter this way: “Hustling day and night, seven days a week … it meant hands and fingers were literally worn down to the nub.”

That is when he and his father began to consider another approach: They could design puzzles using Par’s distinctive cutting style, and Frank Ware’s original silhouette patterns, to be made using laser cutting technology.

When Ware and Henriques had turned down the suggestions of expansion beyond being a small home-based workshop the alternative format would have been hand-cutting in a factory assembly-line type of operation. The couple had not been opposed to innovation: In fact, they relished it. But they wanted to remain respected artisans, working at home in mid-Manhattan, rather than become industrialists.

Of course, Ware and Hernandez never knew, and probably never even dreamed of, the opportunities that laser-cutting enable. The resulting puzzles would not be one-of-a-kind, but with computer-driven laser cutting every puzzle can be absolutely consistent with the designer’s artistic vision.

With laser cutting, the designer can put more time into each design since it will be amortized over many puzzles rather than just one (there’s my microeconomics lessons coming back again!) and a computer-controlled laser machine can reliably cut more intricate patterns than human hands can. As Justin told the NY Times reporter when describing hand-cutting: “Every single piece is an opportunity to ruin the whole puzzle.”

In November of that year Par Puzzles introduced its L-Series of laser-cut puzzles with an inaugural launch that included 20 limited release puzzles. The announcement caused quite a stir among wood puzzle aficionados.

The Russian-based moderator of Facebook’s Wooden Jigsaw Puzzle Club described it as: “A great shift in wooden puzzle industry!” She wrote to Justin Madden to ask him about this initiative and here is his reply:

We have heard from prospective customers for years, that they wish they could buy our puzzles but could never afford them. Our prices have always been dictated by the amount of time designing and hand-cutting these custom made one of a kind works. I thought if there was a way to cut down that time, but still offer the style of interlocking puzzle we make by drawing the puzzle pieces by hand and creating that hand drawn template with our Par signature silhouettes included, then we wouldn't sacrifice originality or style but could offer them cost efficiently in a mass manner.

As you may know however lasercut puzzles are not the same quality as handcut in many ways. We believe there is room for both in our family of offerings and will see where this new L-Series will take us.

In keeping with the Par heritage the puzzles were intended to still be exclusive and they were priced much higher than any other laser-cut puzzles of comparable size - about double the price of Liberty Puzzles. The reaction to them was not quite what John and Justin were hoping for.

Looking at the posted reviews and discussion in the Facebook group a common theme was that people loved the images and puzzle designs, but for puzzles in that price range the execution of the laser-cutting itself was – there is no other way to say this – not up to par.

The problem was discolouration on the image of the puzzle caused by the laser burning which showed up on some parts of the images, especially places that were white or light coloured. This is a fairly common issue with some puzzle brands, especially new companies, and is caused when the laser is not properly adjusted. I wrote about it near the end of this review-essay of another company’s puzzle.

I found conflicting information online as to whether Par was doing the laser-cutting themselves in-house or whether that role was contracted to someone else. (I suspect that it was the latter because laser-cutting involves two big learning curves: translating the design into computer instructions, and operating and maintaining the laser cutting machine to work properly.)

Either way, the Maddens became inundated with unfamiliar complaints about their L-Series products and requests for refunds. By all accounts the company handled these with grace and good customer service, but something had to be done if the L-Series was to survive. It was threatening the whole Par brand. Justin posted a request in the Facebook forum for recommendations for an American company that could do this kind of work in a way that was in keeping with Par’s heritage of very high standards.

The obvious choice for such a collaboration would seem to have been Liberty Puzzles, America’s oldest and largest laser-cut wood puzzle firm. Their reputation for quality gave them a very loyal fan base. In the world of laser-cuts, like Par and Stave before them in the world of hand-cuts, this gives them the ability to charge more for their puzzles than any other laser-cut puzzle company. What’s more, their co-founder/CEO, Chris Worth, is very fond of the fact that his company’s cultural roots come from the Depression-era hand-cutters.

But Liberty’s sales had also surged due to Covid, and despite a large expansion they were already unable to fill the demand for their own puzzles. They discontinued sales to customers outside of the US, and limited US customers to one puzzle per order, and still they had a two month long waiting list.

The knowledgeable members of the Facebook Wooden Puzzle Club had another consensus suggestion for Justin; a small relatively-unknown Canadian company that was developing a solid reputation for having incredibly high standards themselves . . .

Stumpcraft

Stumpcraft was established by Jasen Robillard in 2017. I have already spent much longer researching and writing this review-essay than it took me to assemble the puzzle, so I won’t go into that company’s backstory here. Suffice it to say that I love Stumpcraft puzzles! I had already assembled four of them before this collaboration one, and I have six more of them in my to-do pile. So I’ll be reviewing a Stumpcraft puzzle soon and I’ll tell their story then.

I’ll just give you one teaser about Jasen and his company. From his blog I know that he is a committed and enthusiastic proponent of the global B Corp movement and Stumpcraft is working on obtaining certification from them. Never heard of the B Corp movement? Neither had I. But you can learn more about that social and environmental movement, and what its certification means, from this article in the Harvard Business Review.

Potential spoiler pictures

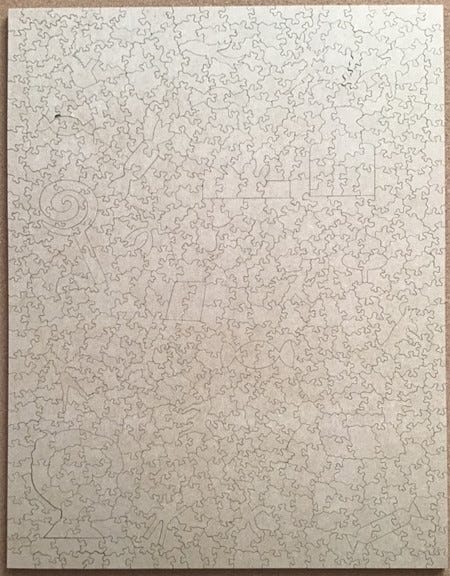

Below is a photo of the backside of the puzzle that shows the cutting pattern, and pictures of the silhouettes. If you are already persuaded to buy this puzzle I recommend that you don’t look at these pictures - discover these treats for yourself.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Hey Bill- thanks for this great review and blog post (*as always). One slight correction I've been meaning to get to when I first read your post: we have B Corp goals and aspirations but have yet to be certified! Don't want to get either of us into trouble with the B Corp police (fortunately, I don't think they exist yet).

First of all, I remember this picture from the Saturday Evening Post, though I wasn't alive in 1944 and must have seen it in some retrospective presentation. I mistakenly though it was by Rockwell and appreciate learning from you about the actual artist, Dohanos. In my mind, I can now honour the correct artist.

Like you, I fondly remember shopping for penny candy. I especially liked those strips of paper with little blobs of coloured sugar stuck onto them. It always amazed me that that was one kind of candy that always provided quite a few pieces for one cent (later, two cents). I was also fond of "watermelon slices," which looked like flattened gum drops.

Today's puzzle is beautiful, though costly. I probably wouldn't spend $179 for one of them, though I do spend that much at one go on other hobby interests. I can see why you do spend quite a bit on your puzzles—you seem to get so much joy out of them—and thank you for sharing that joy with us. The puzzle makers you've written about today likely are also true lovers of their creations.