48. Wentworth binge Part 2: The Railway Station

Another brief (well, brief for me) report about a 250 piece puzzle. It's image is William Powell Frith's 1862 painting of the Paddington Station. (about 3100 words; 24 photos)

This is the second of three postings about Wentworth puzzles that feature the interiors of buildings, and second of five puzzles in this Wentworth binge. Because there isn’t too much to say about the puzzles themselves these postings will all focus more on the research that they inspired. In this case my research was mainly about the railway station itself, Frith’s famous painting of it, and the rather unusual way that the painting was introduced to the public.

For more information about Wentworth puzzles I suggest that you start with the introduction to this series in the previous essay.

The Railway Station painted by William Powell Frith 1860-62

Wentworth Wooden Puzzles (matte green box without flags; plain green bag)

Wentworth stock # 2212

artist – William Powell Frith (1819-1909) painted 1860-62

~250 pcs 8” x 18” (20 x 46 cm) average 3.8 cm²/pc 4+mm mdf

My grandson Reid is now 9 years old and has outgrown the “train brain” fixation of his younger years when playing with toy trains and learning about steam engines seemed to totally occupy his attention. Back then I would look into his ears and tell him that I could see trains running around. I think he may have believed me. His interests have moved on to other things but I still find myself looking for steam train puzzles that I think that he would enjoy.

This puzzle’s image is an 1862 oil painting of the then-still-new London Paddington Station by the artist William Powell Frith. I knew that the completed size of the nominally 250 piece puzzle wouldn’t do justice to such a busy image, and that it would have a subdued colour palette, but I bought it anyway. I enjoy researching fine art paintings, and this one was from the time when steam engines were still a newly-emerging technology (so actually maybe I’m the one who has train-brain.)

Until I did research about its image after I had completed the puzzle about the only thing I knew about Paddington Station was that it was the place where a rather famous bear first arrived in London from Darkest Peru wearing a luggage tag that said: “Please look after this bear. Thank you.” (Presumably someone had helped him get on a train from the Port of Southampton. I know about the Great R+Western Railway from my research about a Chad Valley train puzzle, reported here.)

British folks would know much more about that famous station: It is still the major London terminus for railways from the South and West of England and from Wales, and is a key exchange station for the Underground, including the Picadilly line that connects Heathrow Airport to London. It is the second busiest and second largest railway station in the UK.

But more important in the context of this puzzle and this report, they would know that Paddington Station was constructed the mid-19th century, and that ever since then it has been a major British celebrity building. It was nearly contemporary with the famous Crystal Palace built for Great Exhibition of 1851 employing construction using cast iron and glass, and illumination with gas-light, and has long out-survived that building. Interestingly though, it isn’t credited to an architect but to Isambard Kingdom Brunel, arguably the greatest civil engineer of his time, whose usual projects were designing bridges and tunnels.

This 1862 painting was a celebrity too in its time. In fact, it was eagerly anticipated during the two years that it took for Frith to paint it. I’ll tell more about that after my puzzle assembly walkthrough.

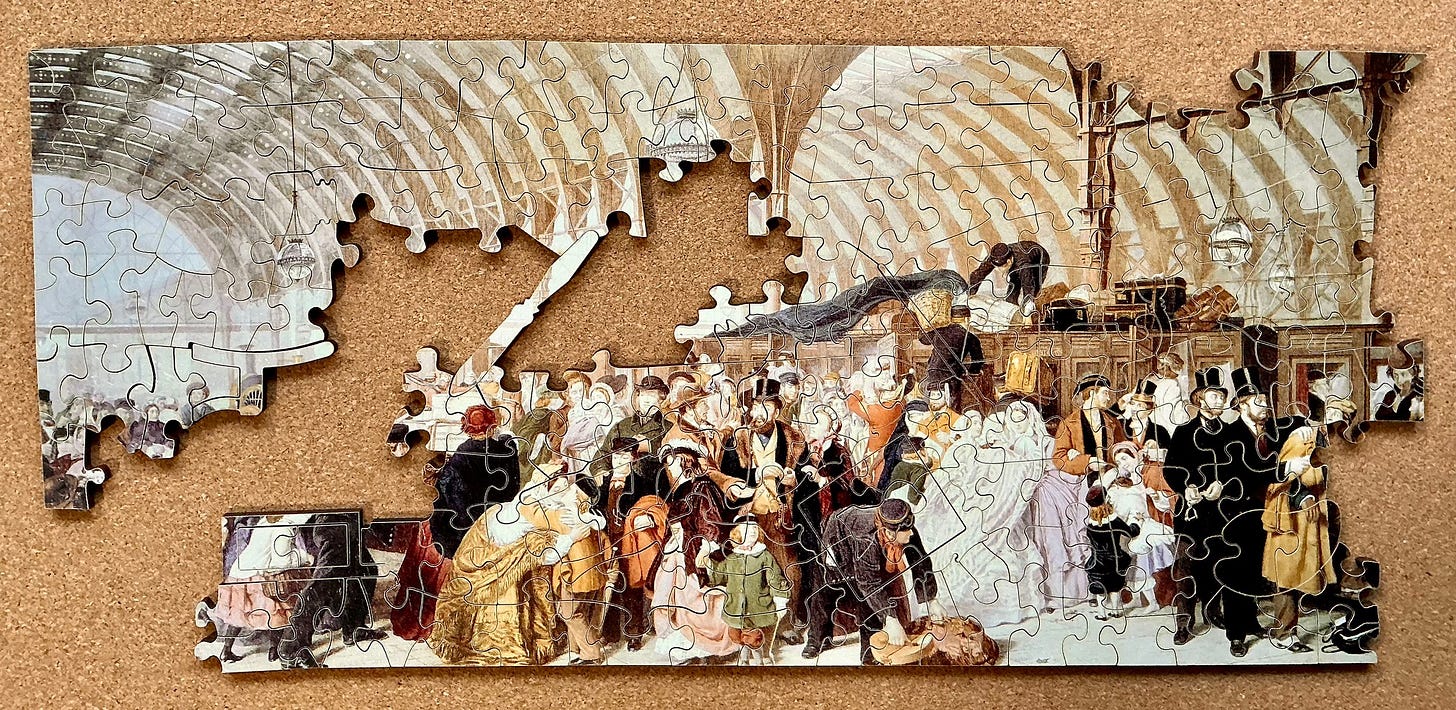

I began, as usual, with a few targets of opportunity:

Note that the above photo shows pieces with straight sides that are not edge pieces. False edge pieces are one of the cutting tricks that Wentworth used in its early years but which it rarely includes in its more recent puzzles.

I was able to put a few of those islands together, and then expanded into pieces that included white (which were pretty scarce in this puzzle.)

The orange pieces in the lower-left of the following photo were also scarce, as were the featureless gray ones that led me into the concentric roof arches:

It is always satisfying to connect two large sub-assemblies, and especially so if it creates links from a puzzle’s top to its bottom:

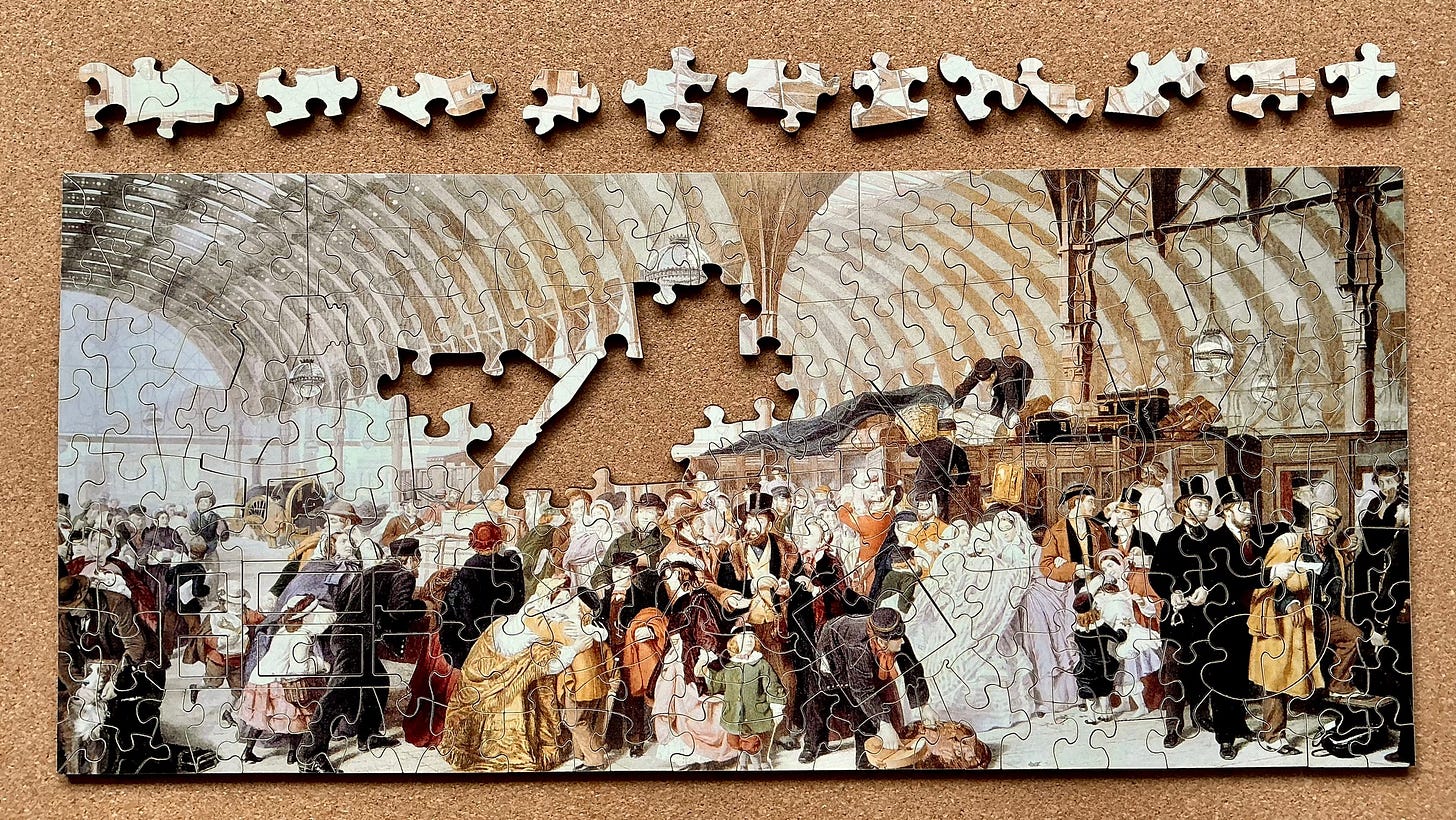

After that it was just a matter of completing the roof and filling in between:

As I expected, when completed this puzzle is much too small to enable appreciation of the image. I don’t know if I will want to assemble it again, but I would possibly buy one with this image made by any puzzle-maker in a 500 or 1000 piece size if one were to become available. It would be fun to discover the finicky little details in the image during assembly.

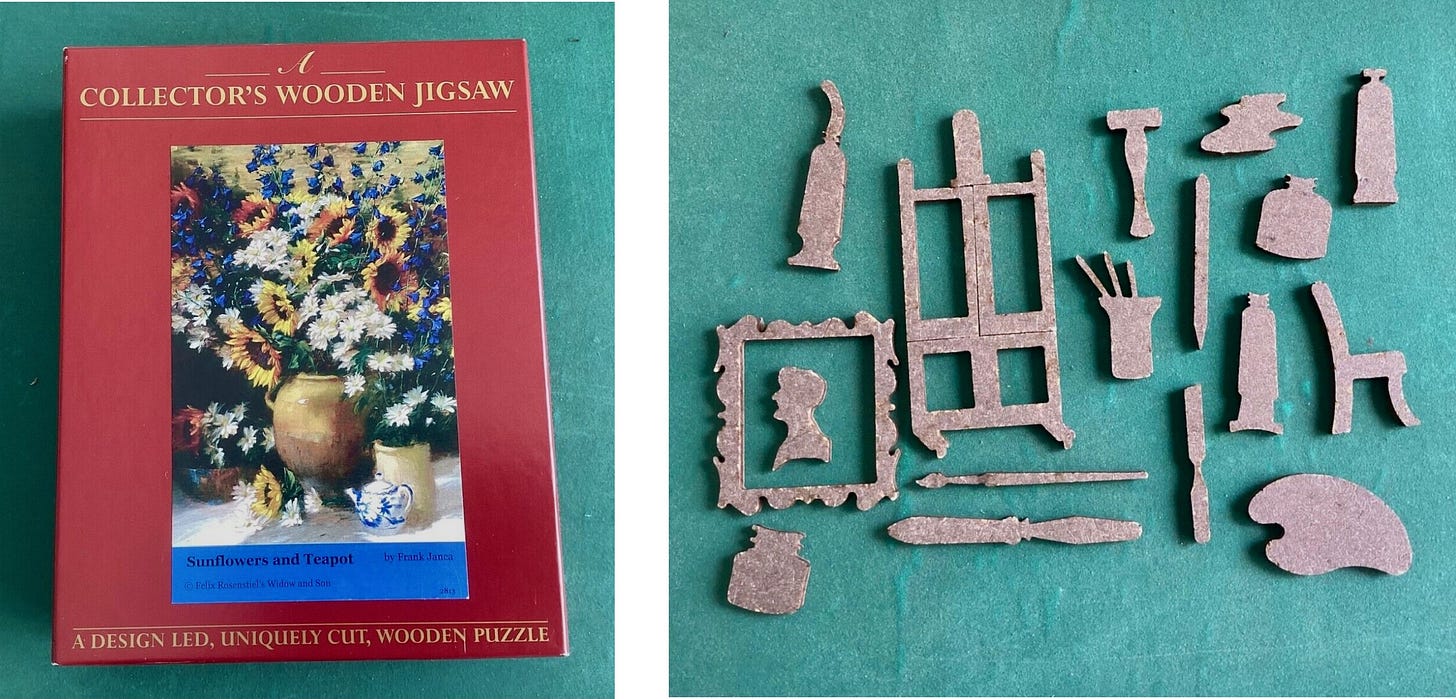

One of the ways that Wentworth keeps its puzzles less expensive, but in my mind rules their puzzles out from being considered to be among the top tier of puzzle-makers even though they are otherwise well made, is how frequently they reuse stock figural pieces and even whole cutting designs in multiple puzzles. In this case the puzzle designer drew from a stock of whimsies considered to be thematic for any oil or acrylic painting. Below are the figural pieces from another Wentworth puzzle that has a very different image. Note that the selection of whimsies is nearly identical to those in The Railway Station.

Now back to the image. In his day William Powell Frith (1819-1909) was one of Victorian England’s most famous painters. As a child he lived in the North Yorkshire tourist spa town of Harrogate where his father was an innkeeper. He showed early artistic talent and his parents encouraged him to develop his skills. He moved to London at the age of 16 to begin his formal artistic education at Sass’s Academy. According to this website, Sass’s Academy “was regarded as an elite institution which set out to prepare (only male) students for The Royal Academy just as Eton prepared its pupils for entry into Oxbridge.”

Just two years later his father died and his mother moved down to London to live with him. That was also the year that Frith was accepted into the Royal Academy School. I presume that this tuition there consumed a significant portion of his and his mother’s inheritance.

He began his professional career specializing in portraits. When he was not doing a commissioned portrait, on spec he would paint figures from literature as well as genre style paintings, which were very popular at the time. Genre paintings are intended to be glimpses into everyday life. At the time they commonly portrayed everyday life in exotic places, or nostalgic views of past aristocratic lifestyles, but Frith’s genre paintings tended more towards contemporary everyday scenes of British working- and middle-class people.

Despite the fact that (aside from his portraits) Frith’s subject choices did not adhere to the Royal Academy’s then most-fashionable style, the quality of his painting was undeniable. He was made an Associate of the RA in 1845 at the uncommonly young age of 26, and a full member in 1853, for which his diploma painting was The Sleeping Model (below). Although that work includes a self-portrait, technically I suppose it would be classified as a genre painting that shows the everyday life of a portrait painter. Frith was “meta” long before that term was invented.

And here is a similar painting called The Artist in his Studio that Frith painted six years later in 1867, just five years after The Railway Station and when he was at the peak of his fame as an artist. In this case it is more clearly a self-portrait as well as a genre painting.

According to this article on the auction house Sotheby’s website, Frith “rapidly became phenomenally popular with the public and respected by critics. Frith was the most admired painter of his time, best known for his hugely complex panoramic pictures of modern life, a genre he created.”

The Railway Station is one of those panoramic masterpieces. The painting was a massive 46” x 101” (117 x 256 cm,) or nearly 4 feet tall by 8½ feet wide. It had been commissioned by the art dealer and entrepreneur Louis Victor Flatow for £4500 – much more than any painting by any artist had ever previously been sold. It also had very unusual conditions of sale. Flatow would own the painting and all of the preparatory sketches, and all copyrights and reproduction rights to them. He also paid Frith a huge additional bonus of £750 for it not to be shown at that year’s Royal Academy exhibition. (Frith was at the peak of his artistic career at the time; there was no question that the painting would have been accepted for the Academy show.)

The reason for that requirement was because Flatow was not buying the painting on someone else’s behalf, nor did he plan on trying to sell it for even more than he paid for it (at least, not right away). His plan was to put it on public display as a one-painting commercial exhibition in London’s cultural heart, Haymarket, and after that he would travel his painting-show to other cities in Great Britain. It would be one of the world’s first one-painting exhibitions.

It took William Powell Frith about two years to paint The Railway Station. In the meantime Flatow got busy piquing the public’s eagerness to see the painting, which he referred to as Life at a Railway Station. He had little problem getting the national newspapers (another relatively new phenomenon in that era) to spread the word that it would be one of Frith’s signature crowd scenes that included people of every class, like his famous 1854 Ramsgate Sands (AKA Life at the Sea Side.) That painting had been bought by the Queen when it had been shown at the Royal Academy Exhibition. . . .

. . . and that it was even bigger and had better story vignettes than Frith’s follow-up to that one, The Derby Day, for which the Royal Academy had had to install special security arrangements to protect the painting from the public who had been dangerously crowding up to closely study its intricate details.

The cost to see Frith’s spectacular new painting was going to be one shilling (the equivalent to about £8 today; $11US or $15CDN) roughly equivalent to what we now pay for movie tickets.

Flatow was a follower of the P.T. Barnum approach to marketing (which perhaps should now be updated and called the D.J. Trump approach) that includes considerable exaggeration and outright lies. For example, he told the newspapers that the painting was ten feet wide (actually it is about eight-and-a-half feet). He also exaggerated how much he paid Frith to paint it, claiming to have paid him eight thousand guineas.

Besides this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see what he told them sas sure to become the most famous painting in the world, attendees would be given the opportunity to subscribe to buy a engraved reproduction of it when it was released. And since he was inventing an entirely new way for the public to see fine art, Flatow also made his own entrepreneurial genius part of the story.

The newspapers ate it all up and the publicity campaign worked! The gentry and middle-class public were indeed eagerly looking forward to seeing The Railway Station, and it’s opening event was the cultural must-attend event for London’s top social tier. The Queen, of course, didn’t pay a shilling to see it or even have to wait for its opening day. She had been given a private showing before the big unveiling, and instead of subscribing for an etching she commissioned Frith to paint her another smaller version of it so that she could enjoy the painting at her pleasure.

In the coming months the painting remained the talk of the town and people poured in to see Frith’s new masterpiece. When the show moved on to other British cities it proved equally popular. As a financial speculation it was clearly very successful venture for Flatow, although no one can put any trust in his claims about attendance.

Actually, for their shilling attendees could only see the painting up close up as they shuffled slowly past it, with an announcer constantly telling people to keep moving, but they could do that as often as they were willing to stand in line for another turn. Further back there were elevated platforms upon which they could stand and look at the painting for as long as they wanted.

Actually, while waiting in line in the luxurious ante-room the attendees were subject to fairly heavy-handed selling of subscriptions for the still-to-be-made engraved reproductions. A “subscription” basically got a person on the mailing list to buy either a plain large scale print or hand-coloured one when they became available.

Frith later described Flatow’s irritatingly persistent salesmanship with a mixture of admiration and anti-Semitic stereotyping: “Flatow was triumphant; coaxing, wheedling, and almost bullying, his unhappy visitors. Many of them, I verily believe, subscribed for the engraving to get rid of his importunity.” (source; The quotation is from Frith’s 3-volume autobiography, published in 1886-88.)

According to Nancy Rose Marshall, whose job title at the University of Wisconsin-Madison is Professor of Nineteenth-Century European Visual Culture:

Those who attended Frith’s one-picture exhibition were availing themselves of a complex multi-layered opportunity: most of all to be entertained by seeing themselves [i.e., their own social class] in representation but also to experience a social event endowing them with a particular form of cultural capital, and finally, to absorb the artist’s genius. …

Viewers were entranced by the novel method of display and happily bought into the myth it helped to produce. Encountering a single painting in a luxurious environment such as Flatow’s was a relatively new experience, as this form of exhibition had only recently come to prominence with such works as William Holman Hunt’s Finding of the Savior in the Temple in 1860, which appeared in Gambart’s German Gallery and subsequently traveled to the UK and Ireland. (source)

The one shilling admission price included a 35 page text-dense educational handbook written by playwright and art critic Tom Taylor based on interviews with Frith. It explained the stories and subtle details in the painting. But, of course, that was too much to read while waiting in line, and the lighting was too dim for reading anyway. But when attendees got back home they could read it learn about things that they hadn’t noticed or hadn’t known about when they had seen the painting.

For example, Frith and his family appear as the group in the left foreground, with his wife kissing the couple’s middle son goodbye as he goes off to boarding school for his first time away from his family. He clutches a brand new cricket bat that he had been given as a going-away present. Frith and his elder son stand behind, with that son looking quite unenthusiastic about the upcoming school term. The couple’s elder daughter stands next to them, holding the hand of their youngest son who is gazing around Paddington Station in wonder.

Beside them is a bearded man in a fur-trimmed coat, who had been modeled by a Jerwish Venetian refugee nobleman who had given lessons in Italian to Frith's daughters. A cabbie is arguing with him over how much he had been paid for the fare.

Further to the right is an upper-class bride and two bridesmaids, near her new husband with his family also there to see them off. And on their right an arrest is being made by top-hatted individuals from the recently-created Scotland Yard Detective Branch. They were modelled by the artists John Brett and Benjamin Robert Haydon, re-enacting a well-known episode that had actually occurred at Paddington Station. The booklet included explanations and trivia factoids about plenty, plenty more of such vignettes in the painting, as well as information about the symbolism and parallels that Frith had incorporated in his painting.

After reading their booklet people might become curious about the things that they had missed. No problem, They could always pay another shilling to see the painting again, or subscribe to get the engraving when it came out. At the very least, they got a lesson from the booklet in how to “read” a Victorian painting.

As you might guess, the fame and acclaim that all of this brought to The Train Station raised its value even beyond its original very high commissioned price. After the London show and its cross-country tour were over Flatow sold the painting and the subscription list (which was the contact information for people who had expressed an interest in buying a print when it became available) to Henry Graves & Co., another London art dealer. It was that company that had Francis Holl’s 26” x 48” (66 x 123 cm) engraving made and which sold both plain and hand-coloured prints to the customers.

I may be going a bit overboard in highlighting the huckster side of this story. In fact, despite the shameless marketing Flatow did indeed deliver a quality product to his customers, displaying painting that is still considered to have been one of Frith’s masterpieces in a setting that would have been among the most luxurious interiors that most of his customers would ever have experienced. (See Prof Marshall’s analysis about that aspect of the event.) And the engraving prints did turn out to be very popular must-have wall-candy for the Victorian public; over 3000 of the 20” x 43” (51 x 110 cm) prints were made in the first edition.

Flatow also changed how people perceived viewing art, going from having people in an exhibition circulating to see many paintings, to everyone viewing the same celebrity painting at once. This innovative format of a one-painting exhibition of a complex story-telling paintings went on to become very popular and only lost its appeal with the introduction of cinema at the end of the century.

As an interesting postscript about the painting, Frith only painted about half of it! And the parts that he did not paint were painted based upon the then-new medium of photography rather than on-site sketches. According to this posting about photographic history:

In his book, My Autobiography, Frith openly admitted his failure to master the "dreadful science" of perspective. It was probably for this reason that Frith asked [pioneer photographer] Samuel Fry to provide a series of photographs which pictured a steam locomotive, a set of railway carriages and the vast interior of Paddington Railway Station. …

Frith recruited the artist William Scott Morton (1840-1903), a designer and former architect, to paint the complicated interior of Paddington Railway Station. Referring to The Railway Station, William Powell Frith later maintained that "every object, living or dead, was painted from nature", but there is contemporary evidence that the artist relied heavily on the photographs taken by Samuel Fry.

The posting then goes on to quote from an article in The Photographic News published in April 1861, well before the painting was completed but after Flatow’s publicity campaign for the one-painting exhibition had begun:

“Mr. Samuel Fry has recently been engaged in taking a series of negatives, 25 inches by 18 inches, and 10 inches by 8 inches, of the interior of the Great Western Station, engines, carriages, etc. for Mr. Frith, as aids to the production of his great painting 'Life at a Railway Station'. Such is the value of the photograph in aiding the artist's work, that he wonders now however they did without them!"

A camera that made 25 x 18 inch (64 x 46 cm) negatives? No, that’s a research rabbit hole that I won’t go down.

Coming up

A puzzle with an image of a servant working in the kitchen, painted by Mary Ellen Best, one of the few professional women artists in early Victorian England.

Thanks, Bill. That you've featured a railway station puzzle is timely. I very recently finished studying a Great Course on "How Railways Transformed the World," a course I urged you to borrow. I saw Frith's painting of Paddington Station during the lecture series; and (I think) that unnamed artist's painting of the updated look of the same station was used there, too.

I like the anecdote about peering into Reid's ears to see trains running around in his brain when he was a train-obsessed youngster. Did he go through a similar dinosaur phase?

As always, I like the way you build up the puzzles sequentially that you discuss in your postings. Today's essay was another good one. Cheers, Greg