47. Wentworth binge Part 1: The Yellow Dining (sic) Room

The beginning of a binge of five 250 piece “vintage” Wentworth puzzles depicting three building interiors and two lifeboats, and lots of research about their images. (about 2500 words; 23 photos)

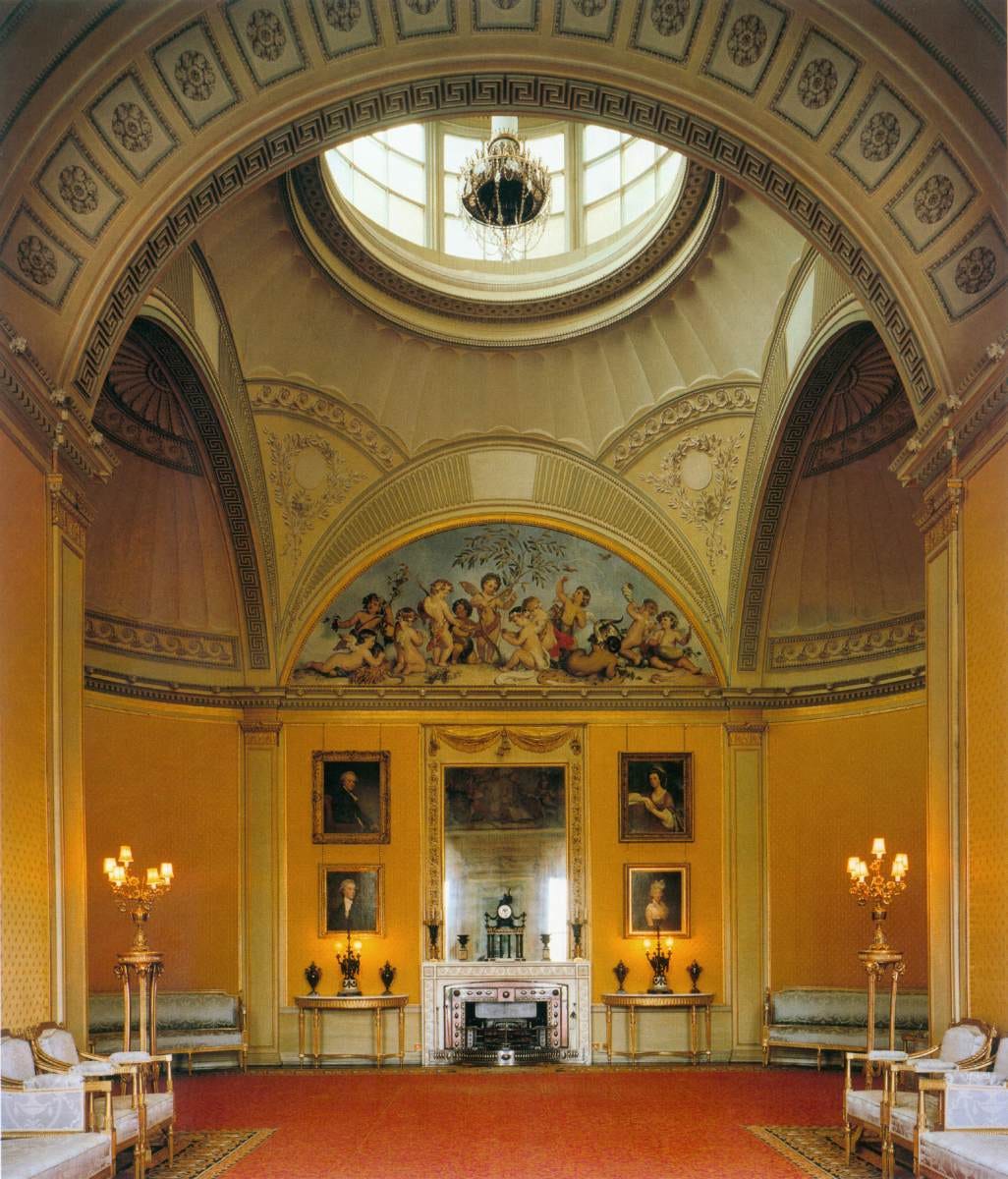

Wentworth’s title of this puzzle is The Yellow Dining Room: Wimpole Hall. But someone got its name mixed up: It is a drawing room, not a dining room.

Reminder: Whenever possible I use fairly high resolution photos. You can usually zoom in to see details.

Introduction

Wentworth Wooden Puzzles, made in rural Wiltshire, England, is the oldest and probably the largest laser-cut jigsaw puzzle maker in the world. They have a huge and ever-evolving spectrum of attractive offerings, their printing and fabrication quality are very good, and they have an excellent reputation for customer service. They also are the only wooden laser-cut puzzle-maker that I know of who make large-piece puzzles for adults who have difficulty handling standard-sized puzzle pieces.

But except for their shaped puzzles, and ones identified as being either “free form” or “extra difficult,” Wentworth’s newer cutting designs tend to be rather formulaic and pedestrian. They are basically comprised of okay whimsies - usually singles but sometimes two or three piece ones - scattered about within a grid-cut matrix of background pieces. The figure pieces may or may not match the theme of the image. Their house cutting style seems to me to be based on the one developed by G.J. Hayter for his Victory brand Artistic series of hand-cut puzzles that they used from the 1930s to ‘80s.

I don’t begrudge Wentworth that formulaic approach. It is a classic, and their 250 or 500 piece puzzles are perfectly suited to win people over from the world of cardboard jigsaw puzzles. The relatively inexpensive (as wooden puzzles go) made-in-England Wentworths have many loyal fans. They were among the first puzzles that I bought when I first discovered wooden jigsaw puzzles, however since discovering the variety of wooden puzzles from other makers I have not ordered any more new puzzles from their catalog. As you may have noticed, I like exploring the diversity of wooden jigsaw puzzle cutting styles.

But I have bough several of their older puzzles made before about 2010 and packaged in green or red boxes. That was before the company had settled in on its current house style of standard cutting, and I think they have more cutting diversity. They can often be quite entertaining, albeit still at the fun end of the fun-challenge spectrum of assembly enjoyment. In my experience (including with the puzzles in this series of reports) the fabrication of these older puzzles is generally of the company’s reliably high quality. Their printing is was also very good, although it is the standard printing on paper rather than the more recently invented UV printing directly onto the wood Wentworth uses now and which I prefer.

But the most important factor for me in preferring older Wentworths is that they are often very inexpensively available online from British vendors (especially in the 250 piece size which often sell for only £10-15 at auction!) Also, the cost of shipping to Canada from the UK is considerably less expensive than shipping from the US if several puzzles are sent in a combined shipment. For that reason, vintage Wentworth puzzles from Britain have become my main go-to “frugal alternative” to keep my wood puzzling hobby affordable, balancing my buying of expensive premium new puzzles and smaller high-grade vintage hand-cut ones.

A report on a 250 piece Wentworth green box puzzle was my third posting in this Bill’s Wooden Jigsaw Puzzles series, and I have used recent Wentworths as my standard-of-comparison for this review of the newly revived Victory puzzles and for this review of ones made by Puzzly. Those postings were very detailed in-depth puzzle reviews. They will give you more information about Wentworth and its history, and will tell you much more about the quality of their puzzles.

This report begins an experiment for me in going back to writing shorter reports, mostly focusing on one puzzle at a time. Because there isn’t much new to say about Wentworth puzzles as puzzles, this and the upcoming postings will mainly be about the research that their images inspired.

The first three in this Wentworth binge series all be green-boxed Wentworth puzzles that have building interiors as their images. They will be followed by a report about two green box puzzles that have images of old rescue lifeboats.

The Yellow Dining Room - Wimpole Hall

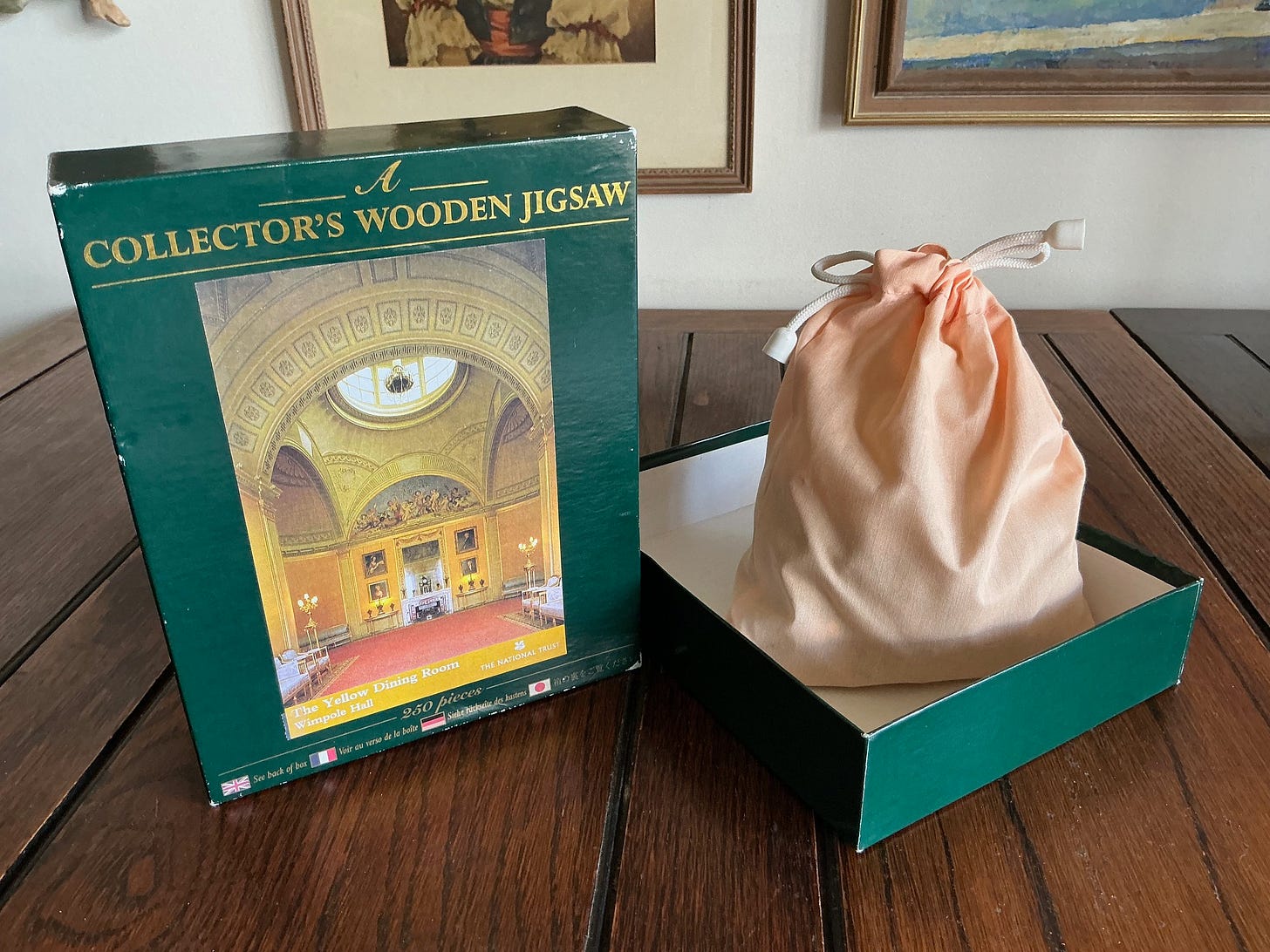

Wentworth Wooden Puzzles (shiny green box; pale peach bag)

no Wentworth stock number on box

photographer not identified; image credited to The National Trust

about 250 pieces 4mm 3ply

I was not attracted to this puzzle by its image. But its cutting design struck me as being what I think of as old-style Wentworth, and because it is a both a photograph and an historic site puzzle I was fairly confident that it would sell very cheaply in its eBay auction. I have noticed a pattern in the online auctions; those types of images seem to be very out-of-fashion in the jigsaw puzzle world and are rarely used in new jigsaw puzzles, cardboard or wood. I do like to get bargains.

What especially appealed to me about this one was that I could see in the photos on the auction website that they were made from plywood. That confirmed that this puzzle was from Wentworth’s very early years in the 1990s. It would be the only plywood Wentworth that I have assembled to date, and therefore the oldest.

I was the only bidder and got it for its £10 minimum bid. That tends to confirm my observation that Wentworth’s are so commonplace in Britain that even the old ones do not attract bids from puzzle collectors. Wentworth puzzles’ final auction prices seem to be primarily based on whether the image is appealing in the context of contemporary puzzle-fashion aesthetics.

It was only after completing the puzzle and was doing my research that I learned what sort of country house this yellow room is in:

Wimpole Hall is on the 3000 acre Wimpole Estate, adjacent to the straight-as-an-arrow old Roman road Ermine Street that runs north from London to Lincoln and York. Archaeological studies on its site have found that there was fairly dense late-Bronze Age settlement there, as well as continued Iron Age settlement and an early Roman villa. The land then remained in continued use through the Anglo-Saxton era, and an old map from after the Norman Conquest shows a moated and fortified manor as being on the very site of the current Hall.

That was demolished and a “new” house was built there in the 1640s and ‘50s. Portions of walls and foundations of that building are still part of the current Hall, well-buried within many alterations and additions that were made over the years. Those were made by various wealthy Earls and Dukes and designed to suit their personal interests as well as to keep up with the latest architectural fashions. I won’t go into all of the various owners and alterations but you can read about them here. But I will tell you abut a few of them.

This drawing room was designed by the celebrated neo-classicist architect Sir John Soane and built in 1790-1795 as part of a major renovation project. At first it was just called “the drawing room,” but later a 2nd drawing room was built in the building with a red motif so this one came to be called the yellow drawing room. At the time the Hall and Estate were under the stewardship of the cultured 3rd Earl of Hardwicke, Philip Yorke. Yorke and Soane had met and become friends 10 years earlier while each was on the Grand Tour of Europe.

For the Earl that was like being in finishing school right after college; a necessary step in becoming a sophisticated aristocrat. For Soane the Grand Tour was a mid-career architectural scholarship awarded to him by the Royal Academy. He was the orphaned son of a bricklayer who was already a rapidly rising architect. He later would become one of Britain’s most fashionable designers in the Regency era and the official architect for the bank of England as well as for the British Government’s Office of Works. Near the end of his illustrious career he was appointed Professor of Architecture at the Royal Academy

Skipping ahead, the home improvements ceased in the late 19th century when the Estate and Hall were under the tenure of the profligate Charles Yorke, the 5th Earl of Hardwicke.

He was a dandy who lived a lavish lifestyle in Victorian times as a drinking and gambling buddy of the Prince of Wales. He wasn’t very good at gambling, especially on horse races, and showed no interest in managing the Estate. In the 1880s he lost the family fortune as well as his social standing. He ran up huge debts and was forced to put Wimpole Hall and the whole property up for sale. No one could afford to buy it, so in 1891 it was forfeited to the Lord Robartes, the sixth Viscount Clifden, the banker to whom he owed most of his debt. (I had to look it up; a viscount is an aristocratic step below an earl.)

Lord Thomas Charles Agar-Robartes had not been seeking a new residence; he would much preferred to have gotten the money that was owed to him. But Wimpole’s location near Cambridge was much more central in England than his own estate, called Lanhydrock in Bodmin, which is near the tip of the Cornish Peninsula.

Robartes and his wife moved in to Wimpole Hall for a short while, but they found the cost of maintaining both Wimpole and Lanhydrock, as well as a Town house in London, to be too onerous. Also, I suspect, “home is where the heart is” so they moved back to Lanhydrock, and Wimpole Hall began to sit empty except for occasional use of part of the building as a hunting lodge.

All of this happened in the late 1880s and the Wimpole Hall sat empty for about a half century. The aristocratic Hall became very run-down, as was its 18th century “model farm,” and the Estate’s 3000 acres of gardens and parkland (designed in 1767 by Lancelot “Capability” Brown became overgrown from neglect.

In 1937 the whole Estate was acquired by George Bambridge and his wife Elsie (née Kipling) who intended to restore the Hall and Estate to their former glory as a passion project. Eton-educated George was a decorated (Military Cross) WWI officer and a British Diplomat. It was his wife’s inheritance and perseverance that enabled them to undertake such an ambitious and expensive project. Elsie was the daughter and only heir to the fortune amassed by the author Rudyard Kipling.

They first acquired the Wimpole Hall under lease right after her father died, but purchased it outright in 1942 when his substantial and complicated estate had finally been settled. But by then they had already been living in the Hall along with an Edwardian-style number of household staff that included “four tall footmen” for five years and had begun planning and implementing its rehabilitation and restoration ever since they had first moved in.

I suspect that after 50 years of neglect structural issues like fixing a leaky roof and repointing crumbling mortar took priority. Unlike most other similar-size buildings the Hall was never requisitioned during WWII for use as a hospital, convalescent home, or other war-related purpose. It had not yet been updated with modern amenities like heating by any other means other than its many fireplaces, let alone electricity and running water.

The Bambridges had only just begun the task of rehabilitation when George died in 1943. Elsie was the executor of her father’s estate and she continued to enforce her entitlement to royalties under British copyright law whenever his works were re-published. Basically, it was her initial inheritance that funded purchase of teh Rumpole Estate and Hall, and the royalties that paid for their rehabilitation and restoration. With the popularity of Rudyard Kipling’s works those royalties were quite considerable and I get the impression that Elsie was a very good administrator.

Her restoration work followed historic site preservation and restoration principles, which would have been tricky given that the building and its landscaping was the product of several generations of evolving architectural fashions. Besides all of the physical construction that was needed, when they bought it the Hall was almost entirely devoid of furniture, paintings and other contents suitable for an early 19th century aristocratic residence. Over the rest of her life Elsie sought out pieces that either once had been at Wimpole, had strong connections to its previous owners, or which were from the proper time period and consistent with the house’s opulent, cultured character.

The couple had no children. When Elsie passed away in 1976 she bequeathed the whole restored Wimpole Estate, and a sizable endowment, to the National Trust so that it could be enjoyed by the public in perpetuity.

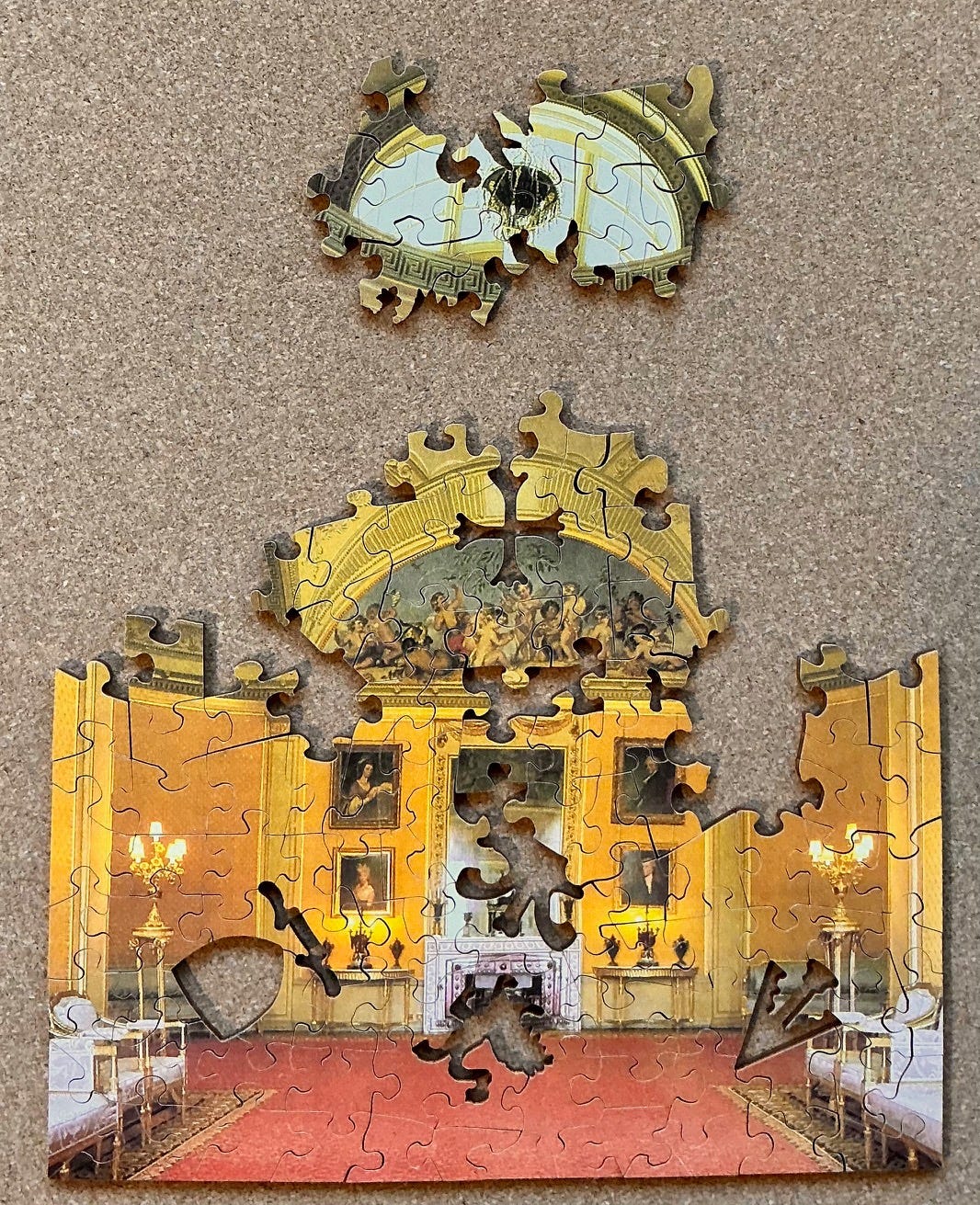

But now back to the puzzle and the yellow drawing room that this National Trust website describes as “undoubtedly the showpiece of Wimpole Hall.”

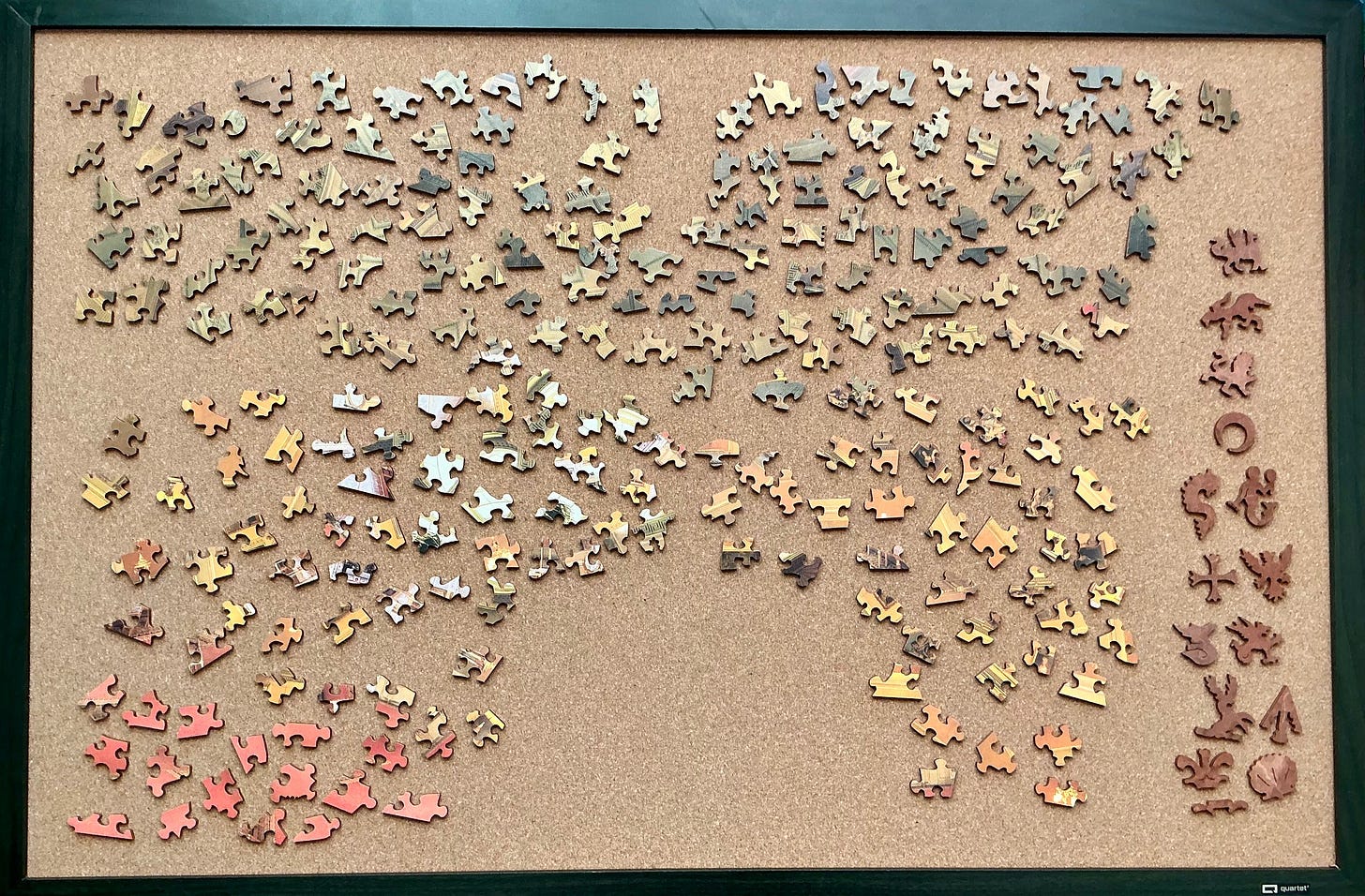

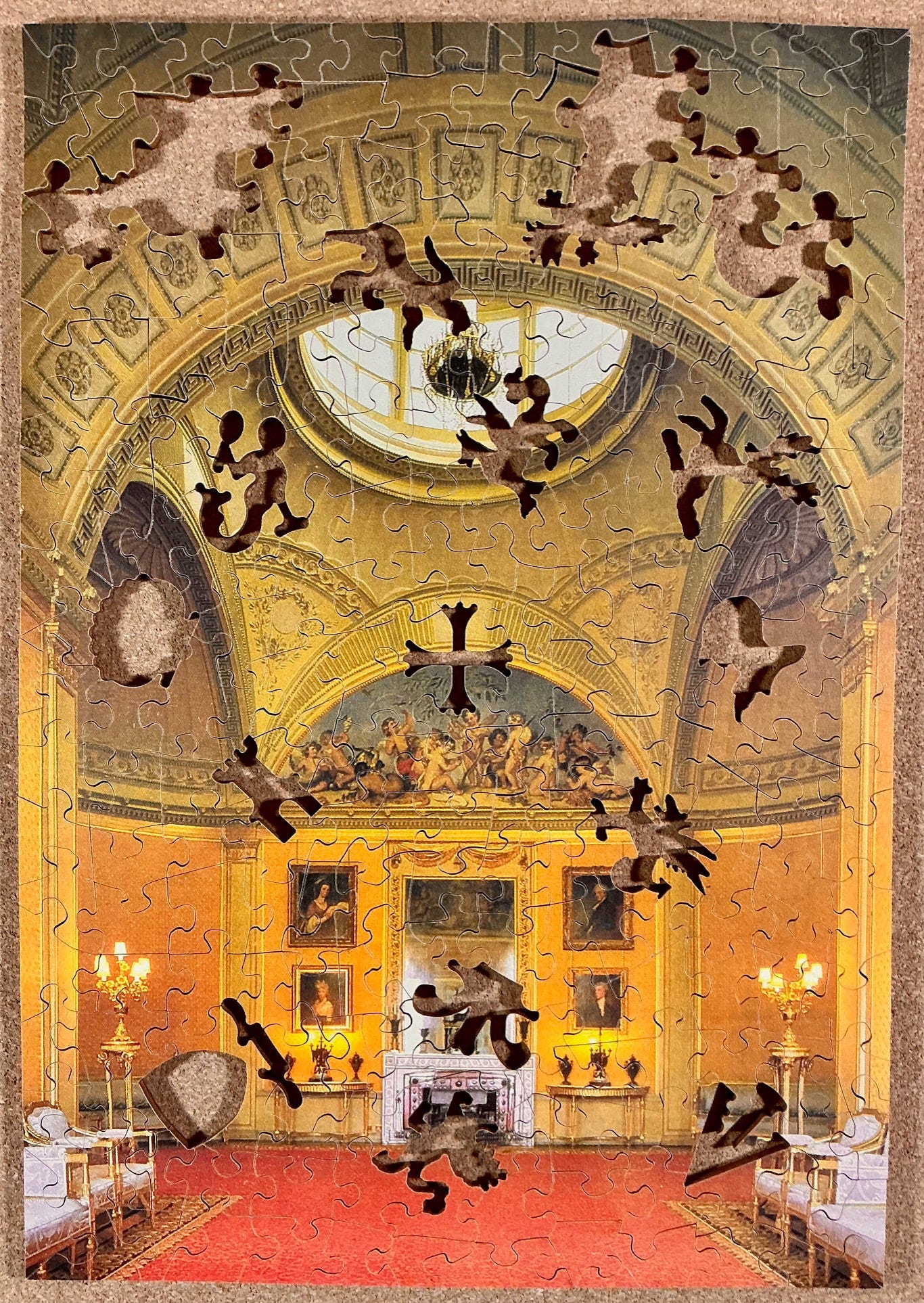

Because I hadn’t bought this puzzle for its image, although I assembled it fairly soon after I bought it I had no clear remembrance of its image except that it seemed to be a rather boring photo of an opulent but uninhabited room. As I flipped and sorted the pieces I was rather surprised to find that relatively few of them seemed to be yellow. Some were red and many more were olive green:

250 piece Wentworth puzzles are never very challenging and I could see on the pieces that the image had a lot of straight lines and various colours and textures, which always help with assembly. It also had figural pieces with very distinctive outlines, which also normally assist in placing pieces quickly. (By the way, the whimsies all seem to be heraldic devices. Since Wimpole Hall was built by and for dukes and earls I think that they collectively are perhaps the most thematic set of silhouettes that I have seen in any Wentworth puzzle.)

It looked like this puzzle risked being too far at the “fun” end of the fun-challenge spectrum for my tastes, so I thought this would be a good opportunity to try out an assembly strategy that adds to challenge: I would see if I could build it without putting the whimsy pieces into place until the very end, or even looking at them for hints during assembly.

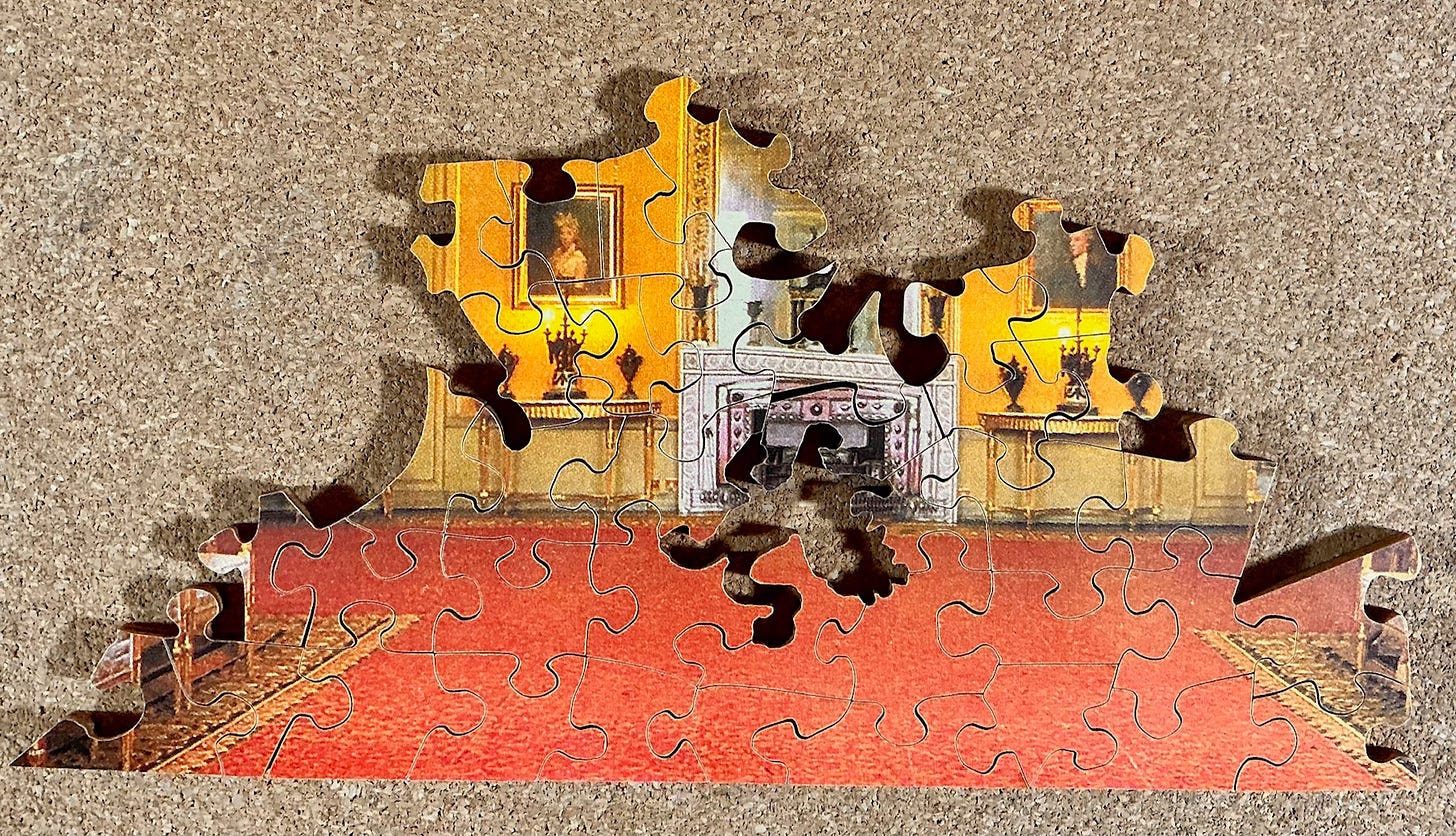

I began matching up the few pieces that had white and the very few that had bright yellow:

Then I assembled the red pieces. A few of the islands from the previous photo found a home with them.

Now the puzzle image had a base from which to grow upward and develop the focus of attention:

By this point I had really come to appreciate this cutting design. The non-whimsy pieces in most Wentworth puzzles are cut in a rather grid-like pattern. They do not necessarily have straight cut-lines that would make the grid cutting obvious, but they have north-south and east-west cuts crossing each other so most of the non-whimsy pieces meet at a 4-corner intersections. It is what is called “random cut” by many cardboard jigsaw puzzle makers, but actually is carefully planned to be efficient; not really random at all. The non-whimsy pieces in this puzzle have a lot more variety and interest than Wentworth’s usual cutting.

I could go on and on about Wentworth’s standard cutting, and about why I like their older puzzles better than the newer ones, but I have already done that in this posting under the heading Cutting design Part 1 – The matrix of Wentworth puzzles.

This was indeed a very good puzzle to try out the save-the-whimsies-for-last approach to assembly. Without doing so it would have been too-easy, but withholding the figural pieces added both fun and challenge to the assembly.

Below is the photo without the cutting lines. According to the Web Gallery of Art this drawing room

is constructed over a square with two lateral apses and a barrel-vaulted long axis. Over the centre space Soane combined a pendentinve and umbrella done which opens into a large glass lantern. … Soane’s commissions up to 1791 had mainly been for country houses. In Wimpole Hall of that year he first put into practice teh idea of top-lighting, a domed interior lit from above, which would become a leitmotif of his work.” (source)

All in all, even with saving the figural pieces for the end this puzzle was only moderately challenging, but it was a fun build and I also enjoyed the research that it inspired.

Coming up …

… in about a week, an essay inspired by assembling a puzzle that has an image painted by one of 19th century England’s most famous artists, William Powell Frith.

In my opinion, Bill, your work on this present #47 posting is extra good. I enjoyed learning why the Wentworth company became successful and famous, plus why you personally prefer to acquire their older puzzles. I also enjoyed viewing the pictures of Wimpole's hall and grounds, the particular batch of figural puzzle pieces arranged on a blue background, and the series of the progressively more-and-more complete Yellow Room. I'm looking forward to the material about lifeboats that you've mentioned may be coming fairly soon. Cheers, Greg