35. Balalaika Part 3: The artist, cubism, and the painting

Information about cubism and the artist Thorvald Hellesen, his 1916 painting Balalaika, and my attempt to understand the image (about 4600 words; 18 photos)

This is the last entry in my three part extended essay about a puzzle that was made for me by Canadian hand-cutter Mary Lee Smyth. The first part told about the puzzle itself and the second one was all about puzzle-maker. This final one is not really about the puzzle at all: It is about the artist who painted its image, the orphic cubist movement with which he was associated, and my attempts to understand the painting and its place in the competing avant-garde art movements of the early 20th century.

Index to Part 3:

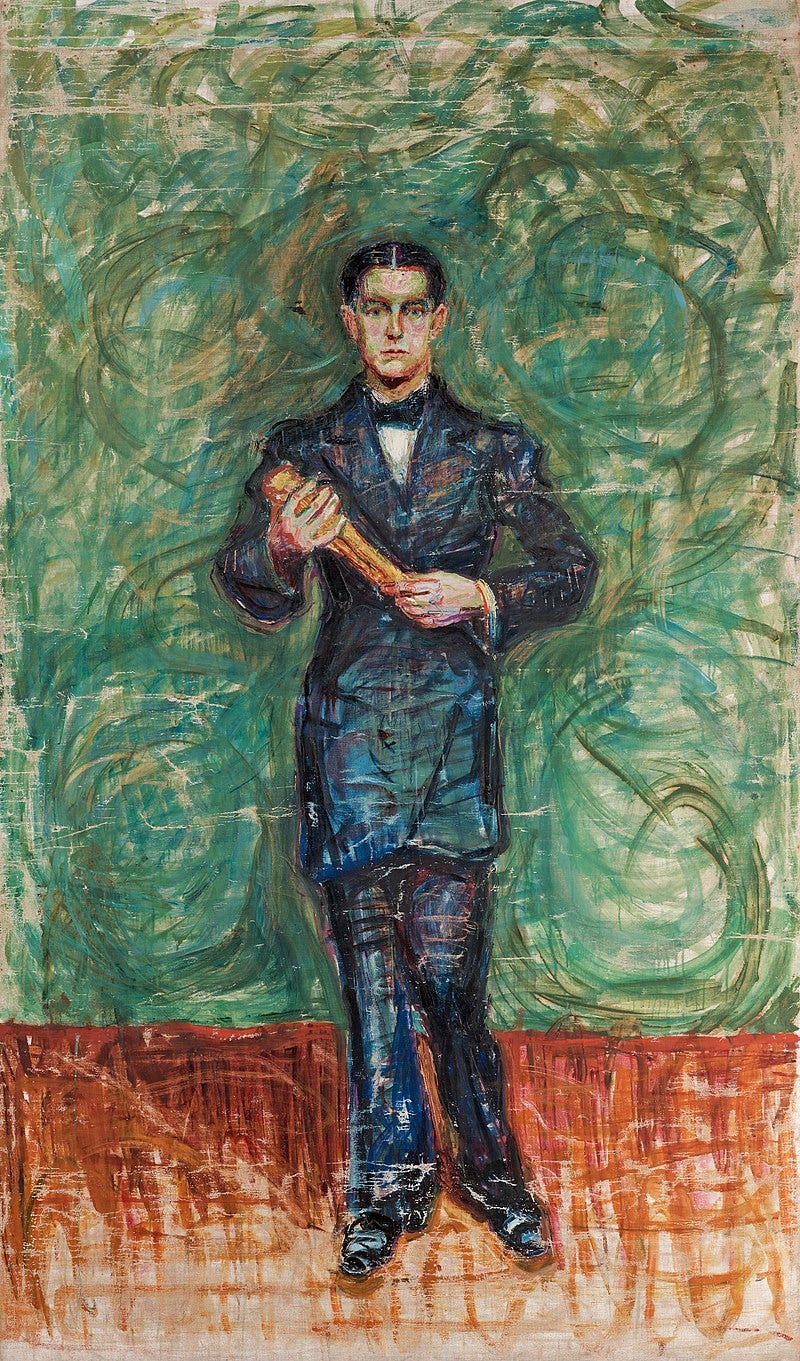

Young Thorvald Hellesen

Thorvald goes to Paris

Private and later life, and mysteries

Balalaika, painted in 1916

The balalaika as an instrument

My attempts to understand Balalaika

Young Thorvald Hellesen

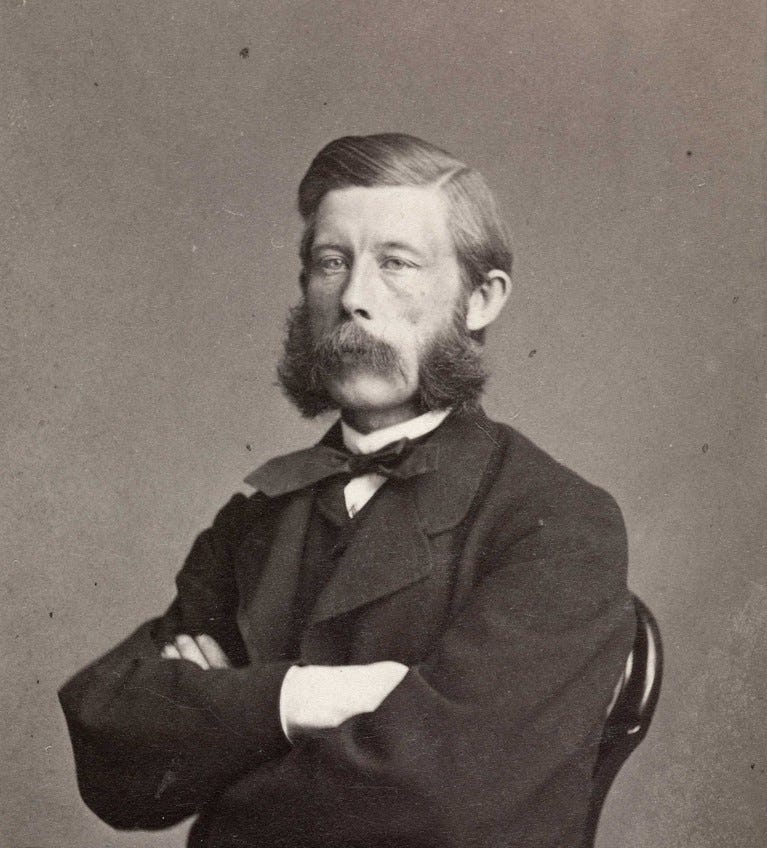

Thorvald Hellesen (1888-1937) came from a well-off family who lived in Kristiana, the capital city of Norway (which was re-named Oslo in 1925.) His father was a barrister at the Supreme Court and his mother was the Prime Minister’s daughter. He showed artistic promise at an early age and after a brief unhappy stint at Norway’s military college he was accepted at the then-recently-established Norwegian Academy of the Arts. There he studied under the renowned Norwegian impressionist and realist painter Christian Krohg. [Note: The various modern art movements can be confusing. My hyperlinks to their names in this essay generally lead to a short summary of their artistic principles and relationship to other movements.]

But young Thorvald was also drawn to the style and panache of the newly-back-to-Norway “bad boy” expressionist painter Edvard Munch, and to other revolutionary avant-garde styles of modern painting that were emerging during that exciting time when the classical approaches to painting were being challenged like never before.

Edvard Munch was acclaimed both as one of Europe’s leading symbolists and as a leading expressionist, two of the many modern art movements that advocated for new ways of thinking about painting and the other arts. Like the impressionists before them, both of those movements thought that painting should blend the reality of form with the artist's inner responses to the subject matter. But Munch’s style of painting was very different from Krohg’s artistic style, and those two artists represented only a few of the many new philosophies of painting that were being debated in Paris during those days. And both of young Thorvald’s role models would have agreed that city was the unchallenged centre of the art world at that time.

Led by French impressionism in the 1870s and ‘80s, new perspectives on art had clearly won out over the hide-bound neoclassicist and romaticist styles of art that were taught at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and which had previously been the only styles that could be shown in the giant annual government-sponsored Salon de Paris art show. But by the early 20th century impressionism itself was already considered by most to be passé, or at least no longer the avant garde of modern art, and many other movements were vying to taking its place. Each had their own manifestos regarding what the new rules should be for artworks to be considered to be worthy of praise, and most of the new art movements were either centred in Paris or very well represented there.

It wasn’t long before Thorvald felt a need to move to that city to continue his artistic education. It seemed to be the place an artist needed to be in order to be part of the revolution in art, and Paris was attracting young artists from all over the world. And the Impressionists had not only broken the hold of classicism on L’École des Beaux-Arts, it had fundamentally disrupted how art was sold. The Salon was being replaced by non-government art exhibitions, and many private art galleries and dealers were becoming part of the Paris art scene. Hellesen applied for and received a scholarship to study there.

Thorvald goes to Paris

22 year-old Thorvald arrived in Paris in 1911. In that year fauvism (with its emphasis on colour over line to instill emotions into artwork) was being eclipsed as the most fashionable avant-garde movement by cubism (with its emphasis on line over colour.) The relative importance of colour versus line was an age-old issue that had long been the core of debates about classical painting theory. The Post-impressionist modern art community in Paris and across the world was split into several “movements” that all made fine distinctions about meaning of art and what it should be trying to achieve via line and colour. They expressed their perspectives in manifestos that go well beyond my ability to understand them.

Cubism, which had been introduced by the previously unknown artists Pablo Picasso and George Braque in around 1907-08 turned the art world upside down (sometimes literally!) with its strong abstraction of a painting’s subject matter and its depiction of it simultaneously from several different perspectives. But by 1911 that movement too was drawing criticism from many modernist painters, poets, art philosophers, and theorists.

They liked how cubism revealed the canvas as being only a two dimensional plane trying to display three dimensional form and four dimensional reality (and it did so without trying to trick the eye using perspective, as artists had been doing since the Renaissance.) According to the influential poet, playwright and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire (who coined the names fauvism, orphism and surrealism) in translation:

The new painters do not propose, any more than did their predecessors, to be geometers. But it may be said that geometry is to the plastic arts what grammar is to the art of the writer. Today, scholars no longer limit themselves to the three dimensions of Euclid. The painters have been lead quite naturally, one might say by intuition, to preoccupy themselves with the new possibilities of spatial measurement which, in the language of the modern studios, are designated by the term fourth dimension.

Some of cubism’s critics, like Apollinaire, thought that cubism did not go far enough in abstracting perceptions from paintings’ subject matter: They called for a complete abandonment of cubism altogether to be replaced by an approach that ignored form altogether much like the movement that much later would be known as abstract expressionism (think Jackson Pollok.)

But in contrast to that, the “orphists” (AKA orphic cubists) main criticism was that Picasso and Braque’s cubism had clearly come down flatly on the line side in the longstanding debate about line vs. colour. By doing so, they thought that pure cubism missed opportunities for paintings to use colour to reveal other important aspects of reality besides its existence in three and four dimensions. Instead of a split from cubism they advocated reconciliation of it with fauvism, but from within the overall cubist movement. That is the crowd that young Thorvald fell in with soon after his arrival in Paris.

Hellesen became part of La Section d’Or (AKA the Puteaux Group), a number of younger generation orphist and orphist-curious artists, poets, and modern art writers and admirers. It included Robert Delaunay, Francis Picabia, František Kupka, and Hellesen’s principle inspirer Fernand Léger (1881-1955) who became Hellesen’s mentor and close friend. They advocated for restoring a balance between the importance of both line and colour within the cubist movement and saw such a style of painting as a way to expand what a painting was trying to achieve. For them, a two-dimensional painting should depict not just what something is, but what it does.

The orphist artistic ambition was not just for a painting to document the appearance of things, but to portray everything about them. Just as music can go beyond literature in telling a story, they saw painting as going beyond a static depiction of its form to documenting what its subject matter did in a place and time. So, for example, a painting of a musical instrument should depict the voice and music of that instrument, not just what it looks like.

According to Art Historian Lin Stafne-Pfisterer with the Norwegian National Museum which now owns Balalaika and who curated an exhibition of Thorvald Hellesen’s art there that opened in 2023:

Picasso and Braque revolutionized the representation of reality. Subject matter was strongly abstracted and depicted from different angles simultaneously…

When Hellesen moved to Paris in 1911, in the years before and during the First World War, he joined the circles congregating around Picasso, Georges Braque and Fernand Léger, amongst others – all Cubists who upturned the norms for what art should be.

Hellesen experimented with one Cubist expression to another. As soon as he mastered the principals of one direction, he seemed to abandon it abruptly and delve into a new direction. In just a few years, he explored…

Orphism - the interest of exploring how to transfer multi-sensory experiences of light, sound, colour and movement to canvas …and…

Crystal Cubism - which used the logic of paper collage - where each field is painted with its own type of brushstroke and texture …and…

Machine Cubism - which was inspired by an increasingly more mechanised life filled with assembly lines, cars, airplanes, etc…

His works were reproduced in journals, and highlighted by several critics. One of which stated that Hellesen’s colourful pictures constituted an ‘unmistakably Nordic influence’ on ‘colourless’ French Cubists.

Over time, the colourful orphic approach to cubism won out over drab or monochromatic pure cubism, and in fact it became the mainstream form of that movement. Most orphic cubist paintings are now usually just called cubist. [Note: I continue to use orphic cubism in this essay to describe Balalaika because at the time when it was painted the debate about the future of cubism had not yet been settled. The painting seems to me to be a fine example of the orphic strategy of incorporating colour in cubist composition.]

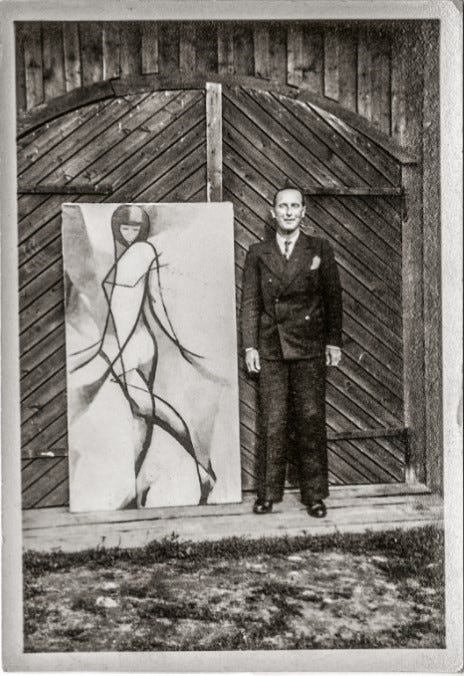

Hellesen is not remembered by most art historians as a major figure in the cubist art movement. His name is not mentioned in either the Wikipedia entry for cubism or the one for orphism, or even it its list of “notable members” of la Section d’Or. He also never recieved much recognition in his home country during his lifetime. He had returned to Norway right after The Great War in 1919 when he and Fernand Léger went there in conjunction with an exhibition of cubist art in Oslo (then known as Kristiania) but the reviews were terrible and sales nonexistent. (I could find nothing online telling what his family thought about cubist painting.) Hellesen returned to Paris where he lived for the rest of his life although he did return periodically to Oslo for visits, and in 1923 he took on an interior design commission for murals, signs and tile-work in that city’s landmark early art deco Sjøfartsbygningen (Maritime Building.)

But his paintings were respected by his peers at the time. His paintings were included in all of the most important Cubist exhibitions in France and elsewhere up until about 1925. One of his contemporaries, the French cubist painter and writer Amédée Ozenfant wrote in L’espirit Nouveau: "Among the Cubists, Hellesen is one of the most interesting, especially because he seems to have reached a clarified aesthetic where color and form play together in a systematic way."

According to the Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg, founder of the De Stijl movement: “the young generation is going further in an artistic expression than Picasso or Braque….Hellesen and Léger are playing an important role in the evolution of Cubism.”

Private and later life, and mysteries

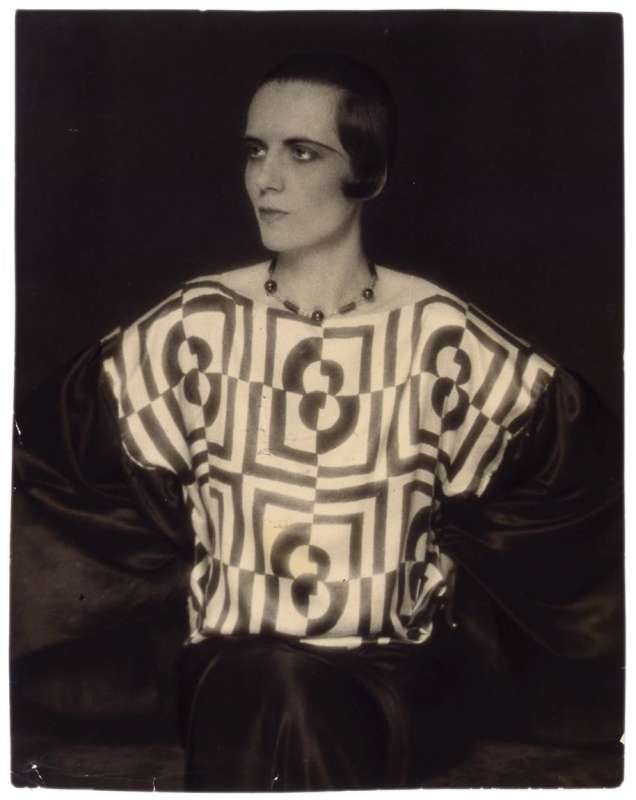

In Paris Hellesen met and married the artist and poet Hélène Perdriat (1889-1969.) She came from a wealthy La Rochelle family but had run away to Paris where she became a familiar and popular figure in various avant-garde art circles. As an artist she was self-taught. Her paintings and illustrations show influences from the various modern art movements of the time, but mainly they strike me more as resembling folk art or the much-later paintings by the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. Thorvald’s marriage to her proved to be a troubled one and eventually broke apart, which might be explained by the number of her paintings and poems that are now classified as lesbian erotica. Despite a lot of searching I could not find the dates of their marriage and divorce.

My online research about Hellesen’s career was thwarted by an absence of information on a number of fronts. For example, I could not find out what he did besides painting during WWI when many of his artistic friends were conscripted and some lost their lives. (Norway was pro-British but officially neutral during that war.)

I did find that he apparently either stopped submitting paintings to major modernist exhibitions in about 1925 or else his submissions began to be rejected from cubist shows about then. It was also about then that he began taking more commissions for interior designs and murals and began doing some textile and wallpaper designs. His output of new paintings apparently continued but in one place it uses that date as when he “became more and more isolated in the French art environment.” In another it says that after about 1930 “he stagnated as an artist.”

I infer that something happened in about 1925 that caused the change in his career and I suspect that it is related to his personal life rather than his art itself. In a couple of places I found references to an affair and marriage to a dancer named Guni Mortensen, and that that affair led to him “gradually becoming estranged from the local art community.” Perhaps 1925 is when his relationship with Guni began and/or became known, and when his marriage to Hélène (who remained very popular in Paris modern art circles throughout her life) ended. Perhaps the Paris art community chose sides as to who was to blame for the marital breakdown. If there is an answer to that it does not appear to be findable online.

In 1937, at the age of 49, Hellesen became quite ill and returned to Oslo to die. His contribution to the world of avant-garde art during his life was soon forgotten both in France and in his home country.

It was about 40 years after his death that Hellesen’s work began to be rediscovered by French and Norwegian art historians, and art collectors and museums began to seek out and buy his works. Today he is considered one of Norway’s great modernist painters. In 2023 the National Museum of Norway opened a major gallery of his works gathered together from various institutions and private collectors. You can do a 3D walkthrough of that exhibition from this website. As far as I can tell, this is Thorveld Hellesen’s first-ever solo exhibition.

Also in 2023, Arnoldsche Art Publishers released a 240 page illustrated book with images of Hellesen’s paintings and essays about him and his work (available in English.) The answers to my questions about him may be in that book. In the past couple of months the auction prices for Hellesen’s paintings have also shot up, with the last two selling for well over twice their estimates. Perhaps we will begin to hear more about this interesting forgotten artist.

You can see more of Helesen’s paintings here and here.

The Balalaika painting

The puzzle that I bought was entitled Balalaika 1920 based on the dating information from the source of Mary Lee Smyth’s high resolution digital image. But I have carefully compared her image (including paint lumps and craquelure) to the above painting by Thorvald Hellesen dated ca.1914-1916 that is called simply Balalaika and have determined that they are clearly the same painting.

Balalaika was bought in a private sale by the National Museum of Norway in 1979. Besides the National Museum, who conservatively still dates it as ca. 1914-1916, all other dating for the painting that I found online says it was painted in 1916. The progression of Hellesen’s other musical instrument paintings (see below) seems to support that date, as does his evolution in experimenting with various styles of cubism in that decade.

Judging by the number of places where I saw the painting online Balalaika is one of Hellesen’s most highly regarded paintings and is possibly his most well-known one. It is certainly my favourite of the ones that I have seen. Here is part of the online interpretation about the painting from the National Museum:

Although we do not know why Thorvald Hellesen chose to depict a balalaika in this painting, musical instruments in general were a frequent motif in cubist paintings. The relationship between the different art forms, such as music and painting, was also a theme that preoccupied many of the artists of the era. The balalaika has its origins in Russian folk music and is often used to articulate a quick, repetitive rhythm, and both musicality and rhythm typify Hellesen’s painting. The clear colours and the way in which the image is abstracted and dissolved into recurring forms help create a dynamic, pulsating visual harmony.

In their making still-life paintings of musical instruments the various cubist artists were following in the footsteps of Picasso and Braque themselves:

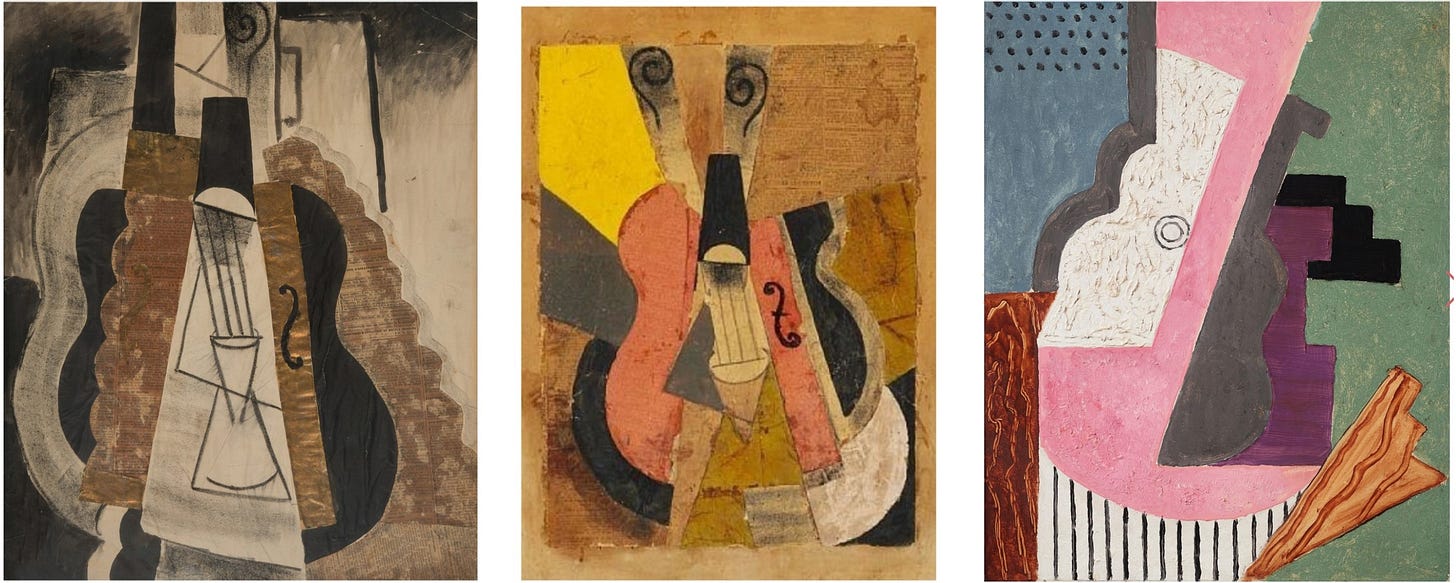

Balalaika is one of a series of several drawings and paintings of musical instruments that Hellesen did at about the same time:

The balalaika instrument

According to its Wikipedia entry:

The balalaika … is a Russian stringed musical instrument with a characteristic triangular wooden, hollow body, fretted neck and three strings. Two strings are usually tuned to the same note and the third string is a perfect fourth higher. The higher-pitched balalaikas are used to play melodies and chords. The instrument generally has a short sustain, necessitating rapid strumming or plucking when it is used to play melodies. Balalaikas are often used for Russian folk music and dancing.

The balalaika emerged as an 18th century folk music instrument and is descended from an oval-bodied Asian-Oriental instrument called a domra or dombra. I get the impression that its closest counterparts in North American folk music might be the banjo or ukulele, but with a voice more like a mandolin. Its three strings are in a very unusual tuning arrangement, usually with the two lower strings being a fourth in a minor key from its top string (E-A-A.)

They have begun to make instruments with 4, 5 or 6 strings that have a balalaika-shaped bodies but those are not true balalaikas. And sometimes true balalaikas are now given guitar-style tuning to G-B-D (mimicking the three highest strings of the Russian guitar) making it easier for guitarists to play, but balalaika purists frown on such a violation of tradition.

Unlike Mary Lee, who plays the ukulele and banjo among other instruments, I am not a musician myself and I don’t understand that tuning stuff all that well; I’m just reporting what I found on the internet. But what I get from this it is that the balalaika doesn’t just look like an unusual stringed instrument, it plays like one too.

My attempts to understand the painting

After I had assembled this puzzle its image seemed to present its own puzzle; how to understand it. It was easy to like the image, but could I understand it as a cubist painting? Before researching to write the above biography of Thorvald Hellesen I knew almost nothing about cubist art except that it was invented and mainly made by Pablo Picasso, and that he first used it in his painting Nude Descending a Staircase. I soon found out that is wrong on all counts!

Well, at least I would be starting at zero with no preconceived assumptions about how to understand a cubist painting, and within that, how to understand an orphic cubist painting. So in addition to the research I was doing on Thorvald Hellesen I ran down even more research rabbit-holes to see if I could try to understand and appreciate this painting’s meaning as a cubist painting and not just its intrinsic beauty.

Having been given the hint from the title I can readily see the forms of balalaikas in the puzzle’s image; at least four of them from straight on and a couple of side views in the bottom-right quadrant. I did note that one of the most important defining characteristics of the instrument – three strings – is not shown at all in Hellesen’s image. That seems odd.

My general impression is that Hellesen might have been intending to depict a trio or quartet of them rather than a single instrument. But a multiplicity of forms is a standard characteristic of cubism so it probably was meant to depict just one instrument.

To the extent that Hellesen was influenced by Edvard Munch and the symbolist movement (he did experiment with various styles) Balalaika might have been intended to represent Russia itself. In 1914-1916, Paris would have had a lot of Russian refugees, and I presume, expatriate Russian balalaika players. I can imagine how Russian folk music played on the instrument could have brought to mind images of the Siberian forests, and I can imagine an autumn deciduous forest as being a possible sub-text in this image.

Although Russian and Ukrainian classical musicians were beginning to compose music for the balalaika it was then primarily seen as a rural folk music instrument played by and for peasants. See here for more information about the instrument’s history, including how it may have been perceived symbolically by an artist during the early years of WWI and the years running up to the Russian revolution. At that time the politically left-leaning artistic community would have been very aware of the news from Russia.

The early years of the Great War were filled with huge setbacks for the Czarist army – almost 5 million soldiers were already killed, wounded or missing! There was much misery for the Russian people, and perhaps a foreshadowing of the military revolts and civil revolution to come in 1917. But personally I cannot see a reflection of those turbulent times in this image unless I were to interpret it as a pile of pieces of chopped up balalaikas, but I don’t perceive it that way. (It is, after all, a cubist painting and to me all cubist images look like the subject matter has been chopped up.)

My understanding of the orphist philosophy is that Hellesen would have been trying to show the instrument’s voice and music. But I don’t know what kind of code the fauvists or orphists used to for having colours represent sounds. My personal impression is that warm colours and earth tones seem to relate more to the lower notes, and the voices of bowed string instruments. I associate cool bright primary colours with higher notes, or with brassy sounds of metal horns or the quick-onset sounds of strummed and plucked instruments like a balalaika. But that may just be me.

There are learnéd studies (e.g., this one) about orphist colour theory, and I presume English translations of orphist writings, but that is a research rabbit hole that seems way too dangerous to go down. (At the very least it might prove that the understanding of orphism that I have developed so far is completely wrong!) So I’ll just go with my own personal impressions about colour and sound.

To understand how an orphist painting might depict sounds and music my next step was therefore to listen to music being played on the instrument. Besides knowing nothing about cubism I can’t recall having ever having seen or heard one played before. But that is a kind of online research that better suits my tastes and abilities than reading high falootin’ analyses by artistic theorists.

I found several balalaika YouTube videos and looked for ones that I thought would represent the kind of tunes that a Paris art student might have heard being played on the instrument by Russian émigré musicians in the early 20th century. First, here is a 1991 field recording of an elderly woman in the Tvar region of Russia playing it to accompany a folk dance. Here is another Russian folk song (Korobeiniki - The Peddlars) that is also largely strumming, and this one and this one have some fancy pickin’.

[Digression: In addition to the above styles of music I also discovered several videos of performances by world-class balalaika musicians of modern compositions, sometimes using electronic reverb and other acoustic effects. I know that the struggling artist Thorvald Hellesen would never heard music like this but they certainly demonstrate what complex music can be played on such a seemingly-simple 3-string instrument. Here and here are a couple of real musical treats (among many.) I don’t usually have music on in the background while doing puzzles, but the next time I assemble this one I think that I’ll put a playlist of balalaika music on to accompany and inspire me.]

From those folk songs I could sometimes envision the voice of the balalaika as dancing tongues of flame and the image on my puzzle has the right tones of yellow and orange to convey a flame-like effect. But the dominance of red with those colours gives the image more of the mood of smoldering fire than a dancing blaze. I can’t hear smoldering in balalaika music. But, as discussed above in the Review portion of Part 1 of this essay, I don’t even know how well the colours in the puzzle’s image conform to the colours in Hellesen’s painting. But that doesn’t help. In my mind, the warm and muted browns in the Museum’s photo of the painting do not convey any impression of fire at all – firewood maybe, but not fire.

Thus, if this painting was intended to depict the voice or music of a balalaika with its colours I can’t recognize that in this image (but then, I didn’t research the ins and outs of how orthist colour theory was supposed to work.) But while I can’t find music in the colours I could certainly can see musical rhythm, order and harmony in the composition of the painting.

It has curved shapes radiating outward from the various centres that appear to be balalaikas’ dark sound-holes, the way that sound radiates out in circles at the speed of sound from its source. The patterns repeat, just as music has repeating passages. So in that regard it probably does live up to the orphic cubist objective of showing the intangible element of music in a painting. And it does so in a way that seems beautiful in itself even to someone who does not understand (or even like) most cubist paintings.

You covered a lot of ground in this essay, Bill. Thanks for your thorough effort. I find myself more interested in simply looking at the different creations by 20th century artists than in figuring out whether or not I know for sure what genre categories they represent. I found myself chuckling as I read through the many -isms to which you made reference.

I really like the balalaika painting. It was a wonderful picture for your personally commissioned puzzle. I am glad that Thorvald Hellesen's work got rediscovered after apparently having been ignored for decades.

Best regards,

Greg