34. Balalaika Part 2: Mary Lee Smyth – puzzle-maker

How Mary Lee Smyth got into wooden puzzle-making as a top professional, then it became a hobby, and began again doing it professionally during the Covid lock-downs. (about 4200 words; 13 photos)

This is Part 2 of a three-part essay that emerged from my experience assembling a wonderful hand-cut puzzle with an image by cubist artist Thorvald Hellesen. Part 1 was a detailed review and assembly walkthrough of the puzzle, and Part 3 will be information about the image’s artist, the orphic cubist art movement, and my attempt to understand the painting in the context of that movement. This part tells about the Canadian hand-cutter who made the puzzle, Mary Lee Smyth.

Index for Part 2:

Introduction - responding to Covid

A surprise revelation

The early years

“The big time”

The hobby years

Smyth Puzzles

Introduction

.

Introduction - responding to Covid

When the Covid pandemic began in early 2020 many people found themselves both without their regular employment and forced to spend almost all of their time in “social isolation” at home. Many quickly became tired of screen-oriented recreation and turned to hands-on activities like assembling jigsaw puzzles. For most that meant the very-affordable cardboard ones. But for some, those stressful times when so many other forms of recreation were often unavailable brought a desire to experience the luxury of the higher-quality wooden ones. There are two general types of wooden puzzles - ones made using computer-controlled laser-cutting equipment and ones made by the traditional but labour-intensive process of handcrafting them using a scroll saw.

During the first two Covid years the demand for wooden jigsaw puzzles greatly outstripped supply. Companies were running out and could not make them fast enough to keep up with demand. Because the orders were piling up some wood puzzle makers had to begin rationing them even to their long-term customers. Some creative home-bound people saw an opportunity to start a new hobby and/or home-based business by making jigsaw puzzles.

The technology for making cardboard jigsaw puzzles does not scale-down to home workshop size. But making wood puzzles is possible at that scale using either the computer-controlled laser-cutting technology machines that cost about $3-6000, or scroll saws that begin as low as $150 for a hobbyist-grade model or $1000 for a professional-grade one. In both cases, the learning curve for making puzzles is not too steep, but learning to make them well takes both time and experience.

By mid-2021 over well over half of the British and North American wooden puzzle brands that were available for sale on the internet were companies that had started up since the beginning of Covid 1½ years earlier. One of those brands is Smyth Puzzles, a start-up company that makes hand-cut puzzles. Actually, except for getting help from her son Graye for technical matters like designing her website, Smyth Puzzles is really one person – Mary Lee Smyth, who lives in Kingston, Ontario.

Faced with a large market but expanding competition her main marketing strategy has involved online sales and generating word-of-mouth recommendations. So Mary Lee began to participate in an online international Facebook discussion group called Wooden Jigsaw Puzzle Club. That is one of the online places where many people (like me) were going to learn more about this rather esoteric branch of jigsaw puzzling ,to share information about this hobby, and to read about the various available brands. Participants in the group include puzzle-makers, puzzle-buyers, and people who want to sell the puzzles they have bought and assembled so that they can buy other ones.

Mary Lee posted pictures of puzzles that she had just completed, and gave thoughtful answers when people asked questions, especially technical ones from new hand-cutters (such as by posting a video showing how to tell if a blade is tensioned tight enough.) It was clear that even though her company was new Mary Lee had sufficient experience to give knowledgeable advice.

Wooden puzzles come at various levels of quality and price-points. Some are from makers who are on the early steps of the learning curve who have to price their puzzles accordingly. At the other end of the price spectrum is the well-established Stave Puzzles company, founded in 1974, that makes the most expensive wooden jigsaw puzzles in the world.

People who followed the link to the Smyth Puzzles website found that her prices were in the mid-range for hand-cut puzzles but limited information about where she was on the learning curve. But soon various participants in the online forum, whose opinions people had learned to trust, began posting images of a Smyth puzzle that they bought and had just enjoyed assembling praising its high quality. Mary Lee always posted polite responses thanking them for their kind words, but she never volunteered further information about when or how she had learned to do puzzle cutting.

A surprise revelation

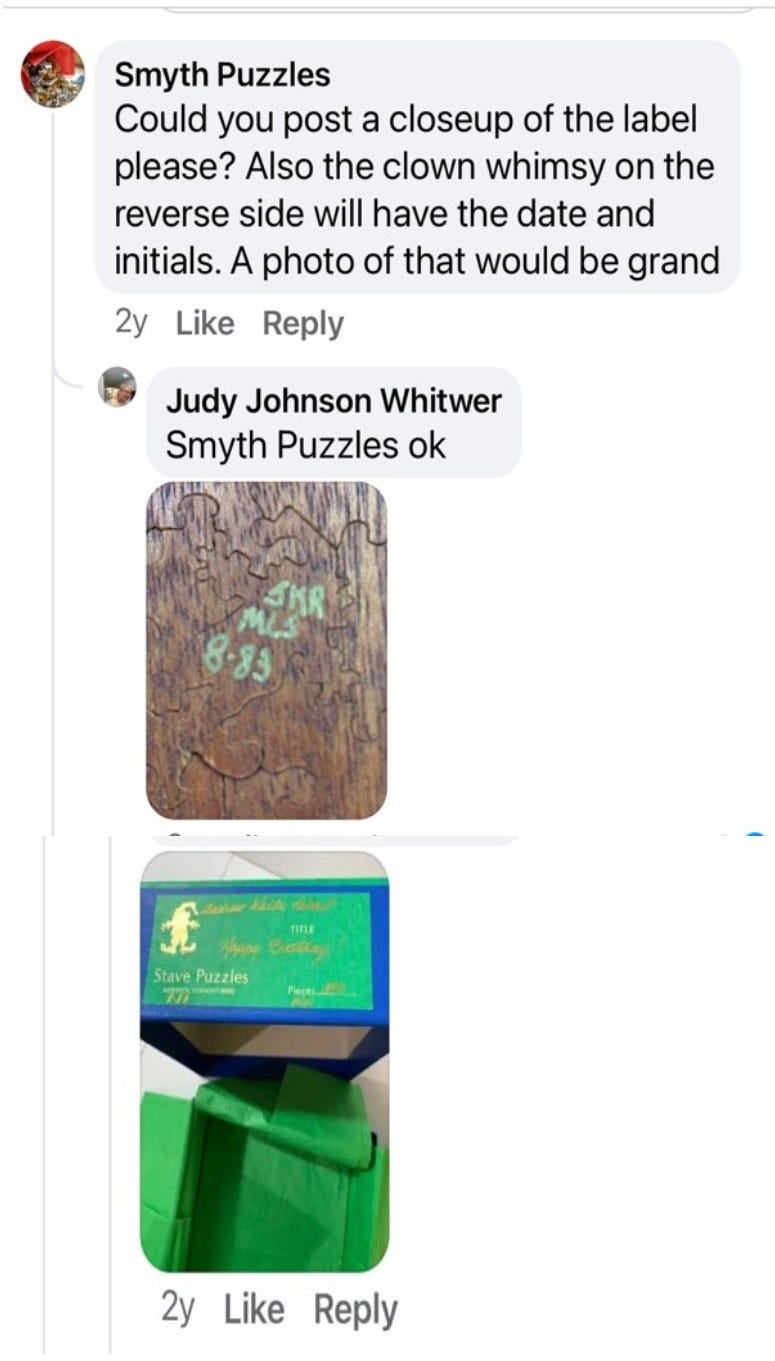

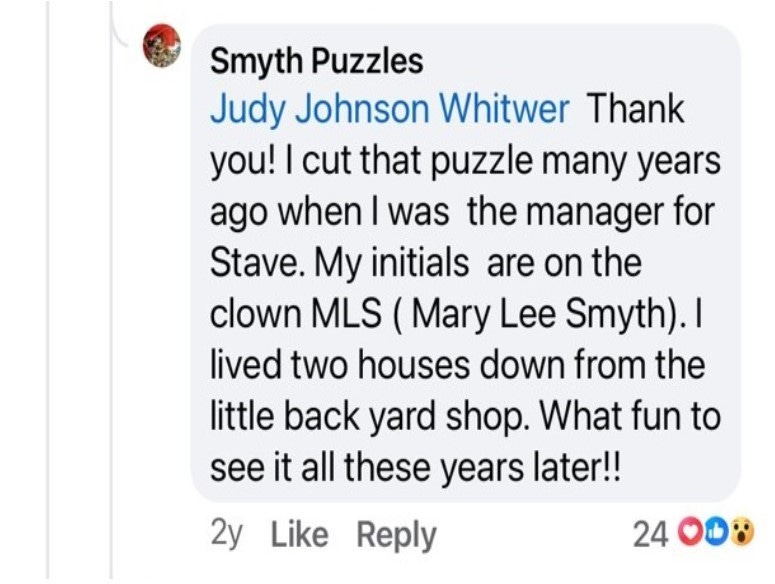

It therefore caused quite a stir when the following thread appeared in the Wooden Jigsaw Puzzles Club discussion group (most relevant messages only):

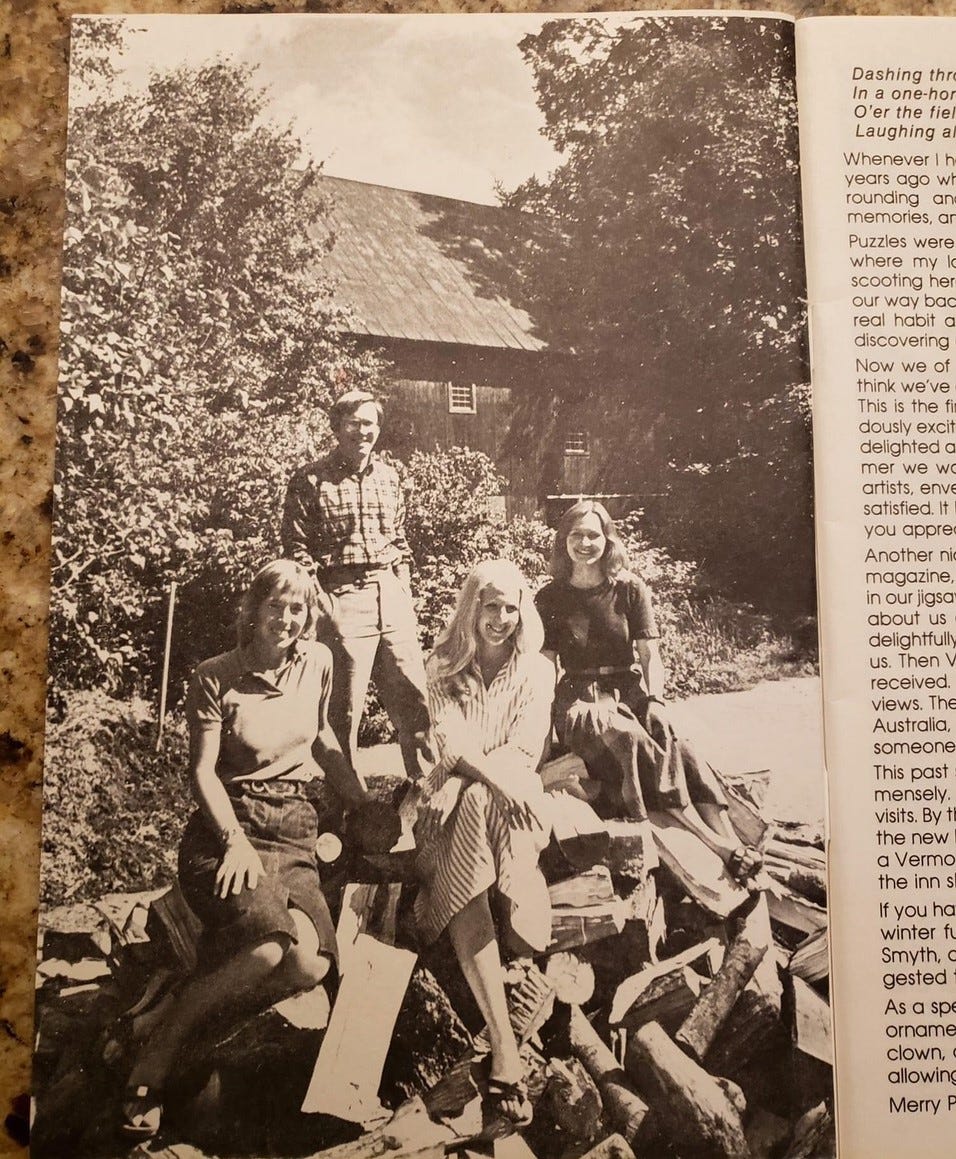

Mary Lee had been manager at the prestigious Stave company in its early years and had never bothered to mention it when she started her own puzzle-making business?!? As you can imagine, that revelation caused quite a reaction in the online wooden puzzle community. Among the responses that I left out were people congratulating Judy on her good fortune to have gotten such a fine puzzle, speculation about how much it would be worth now as a collector’s item, and amazement that Mary Lee had never previously mentioned her early role at Stave. And as manager no less! Mary Lee followed up by tracking down and posting a photo from a 1981 Stave catalog (shown later below) and offering to send copies of the whole catalog anyone who requested it.

I discovered that thread when I joined the discussion group a few months later, after I first discovered the joy of wooden jigsaw puzzles. It gave me great pride to find that fellow Canadians Mary Lee Smyth and the late Paul Simpson were both highly-respected hand-cutters and among both the most thoughtful and helpful contributors to the group.

That is part of what motivated me to splurge and buy this puzzle — reviewing it for this newsletter/blog would give me an good excuse to learn more about this talented but introverted craftsperson. People tend to not ask snoopy questions in the Facebook group, but Mary Lee has been very forthcoming in answering the questions I put to her in my emails and in our telephone interviews for this essay. (Thank you Mary Lee!)

The early years

Mary Lee Carrol (her maiden name) was raised in Connecticut and in Vermont where her family had lived in the small town of White River Junction for generations. As a young girl she was very involved in arts, crafts and music, as were her whole family – especially her mother who would buy her supplies and tools for whatever creative medium she wanted to put her hands to. Young Mary Lee learned that she wanted her future adult life to be one in which she could express her creativity.

After high school she went to the University of Connecticut and received a Bachelor of Science degree in Interior Design which provided training in drafting and design theory. But when she graduated in the mid-1970s there was a major economic downturn (if you are old enough you will remember it as “the oil crisis”) and jobs were scarce for new graduates.

She could not score an interior design job so she turned to plan B and got credentials to become an art teacher. Her first teaching job was in the elementary school in Norwich, Vermont. To supplement her teaching salary she moonlighted as a part-time waitress at the local Holiday Inn. In the winter of 1978/79 that is where she met her future husband, a Canadian named Randall Smyth, who was a creative person like herself. He was a jewelry-maker who had a BA degree in silver- and goldsmithing who had come to Norwich for a skiing holiday.

1980 was a momentous year for Mary Lee. She married Randall and they bought a house on Main Street in Norwich where they could live and he could have his jewelry-making studio. Two houses down from them a fellow named Steve Richardson has started a hand-cut jigsaw puzzle-making business out of an addition to the back of his garage. He he had a son who was one of Mary Lee’s art student and he was commissioning artwork and whimsy designs from Mary Lee for his puzzles. In 1980 he offered her a full-time job as both an image designer and cutter-designer at a better salary than she had been getting as a teacher.

She jumped at the opportunity, partly because it was the kind of creative work that she had always wanted, but also to get away from the never-ending parade of colds, flus and other bugs that the teaching profession entailed. The job involved not just continuing to design images and whimsies for the company’s puzzles but also learning how to become a first-rate cutter and cutting designer.

The big time

In the 1970s until about the turn of the millennium, although lots of wood puzzles were being made by toy manufacturers for kids there were few companies making them for adults. All of the American wooden puzzle manufacturers that had thrived before WWII had ceased making them for adults, beaten down by an abundance of cheap cardboard puzzles (and laser-cutting of jigsaw puzzles had not yet been invented.) There were only a few individual craftspeople engaged in the hand-cutting them, mostly in New England which has always been the centre for wooden puzzle-making in the US. They were mostly amateurs or semi-professionals who primarily made them as a hobby but sold some to word-of-mouth customers as a side-gig.

But Mary Lee’s neighbour had bigger ambitions than that. He also had an MBA with a knowledge of a micro-economic phenomenon known as prestige pricing or veblen goods, and a knack for marketing. He had grown his small business from being a partnership with a puzzle-maker into a team of himself, his wife Martha, and three cutter/designers. That made him perhaps the largest wooden jigsaw puzzle maker (for adults) in the country at that time.

Richardson’s marketing strategy was for his “brand” to be as an ultra-premium luxury product for the wealthy. Par Picture Puzzles, under Frank Ware and John Henriques, had been extremely successful with that strategy from the 1930s-‘60s (see my essay about that company here.) But when Henriques passed away in 1972 and Ware retired soon after that it left their niche to potentially be filled by someone else. He aimed to be that someone else.

By now you have probably recognized that the company I am talking about is Stave Wooden Jigsaw Puzzles, which both The Smithsonian and Forbes Magazine later referred it as “the Rolls Royce of jigsaw puzzles.” The company wasn’t famous back then, but it was beginning to become well-known among some wealthy jigsaw puzzle fans who were willing to pay whatever it takes to get very high quality. For a while at that time, one customer, the wife of an old-money industrialist, had a standing order for three custom-made Stave puzzles every week.

Richardson knew that his personal strengths were on the marketing and public relations side of things and not in the making of the puzzles. He could do all of the roles in the company, but it made better business sense to leave the book-keeping and payroll side of things to his wife Martha, and customer relations, design, puzzle making and fulfillment (shipping) to “the girls” that he for hired. (Yes, they still talked that way in the early 1980s, and unlike in Britain, the American puzzle factories in New England had traditionally hired only women to do puzzle-cutting.)

The production team worked under a team leader, called the manager. She assigned who would be responsible for correspondence with the individual clients and design and cut their puzzles, as well as be responsible for ensuring that the work was up to the company’s high standards. About nine months after she started working there, Carol Fisk, the manager who had taught Mary Lee how to design and do scroll-saw cutting, had to leave. It was a team decision that Mary Lee should be their new manager despite the fact that at 26 years old she was the youngest and least experienced among them.

Mary Lee worked for Stave for five years, until another financial downturn, the biggest one since the 1930s Great Depression (that is now known as the Great Recession) forced Steve Richardson to greatly scale back the size of his company. Obviously, the company survived this huge setback, but Mary Lee was laid off.

The hobby years

She wasn’t out of work for long. She became the sales manager for Randall’s jewelry business. That wasn’t just a small studio shop on Main Street in Norwich. He sold and took orders at wholesale trade shows held for buyers from gift shops and jewelry stores and chains, as well as taking commissions from individuals for custom-made silver-smith pieces and art-jewelry. But selling and dealing with the buyers was his least-favourite aspect of being a jewelry-maker so he welcomed Mary Lee taking over those roles, leaving him more time to design and make the products.

Mary Lee proved good at her side of things and their jewelry business continued to prosper and grow. The vendors that sold Randall’s jewelry at retail ranged from the Ben and Jerry's Ice Cream gift shop (silver cow earrings as one of their top-of-the-line souvenirs) to the gift shop at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburg. Perhaps his most prestigious outlet was the Alianza Contemporary Crafts Gallery in Boston, whose owner and proprietor was Karen Rotenberg, one of America’s foremost collectors of modern art jewelry.

Over those years she did other stuff too; stuff like giving birth and raising their son Graye.

When Graye was 4 years old he showed signs of being a prodigy in mathematics. They sold their house in Norwich to buy a farm near Sharon, VT where they had a particularly good elementary school (he got special tutoring from a university mathematics professor) and where the family could live the country life and have horses. Looking ahead, they moved there because it was also near the Sharon Academy that would better be able accommodate his high school education.

In 1995, with a solid slate of jewelry customers nailed down for Randall, Mary Lee was able to move on, responding to an advertisement to become a full-time house designer for Vermont Log Building Inc, which has since become Real Log Homes. The job involved assisting potential clients to design and build their own dream homes. That was very close to achieving her long-time desire to become an interior designer. She is quite proud of the fact that one of the homes that she helped a couple design is still included in that company’s “inspiration gallery.”

It was about that time that she got back into to making jigsaw puzzles, sparked by the gift of an old Delta scroll saw from an elderly friend who was clearing out his workshop and which he wanted to go a good home. He offered it to Randall but Randall said that it was Mary Lee who was the one who could put it to good use. He helped her restore it to good operating condition and she began cutting puzzles again for the first time in 10 years.

It wasn’t too long before she realized that she was used to making some of the best puzzles in the world using a better saw, and she was still a perfectionist. She upgraded, and then upgraded again, to the then-state-of-the art professional-grade DeWalt scroll saw that went on to serve her well for 25 years. She was also very fortunate at being able to find a free heat press which is the only other major piece of equipment that is needed to make fine wooden jig-saw puzzles (other than a printer, but printing services and art-prints were readily available.)

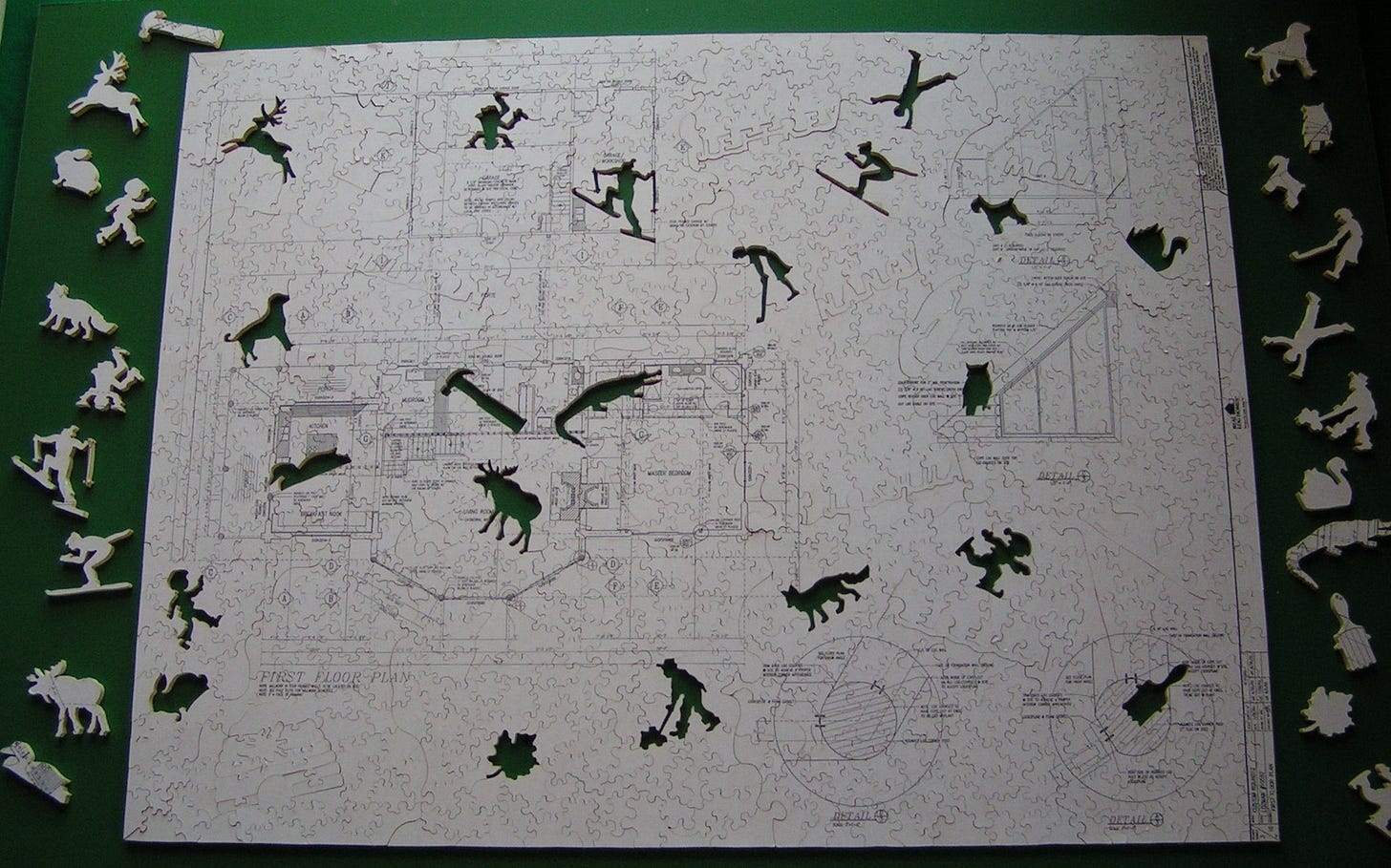

For many years Mary Lee continued to make jigsaw puzzles as a hobby and gave them to friends, colleagues and some of her log building design clients, as well as picking up some commissions from word-of-mouth. The puzzle image for clients would be the blueprint of the home that they had jointly designed. Nominally these were gifts, but I wonder if they might have been subconsciously been revenge for frustrations that she had working with them. Blueprints make very challenging images for jigsaw puzzles. She received a letter from the husband of one of her clients who had received such a puzzle in 2006. He said that his wife had become obsessed with it and hardly left the puzzle table for three days, even sleeping close to it.

I became interested in Mary Lee and Randall as an artistic couple. While interviewing Mary Lee for this article I asked her if she could send me a photo of an example of his work. I expected that she would send a picture of his fine jewelry or a silversmithing piece to show of what a great craftsman he was. Instead, she sent me this photo of a gift from him:

She explained it to me:

Here is a favourite albeit humble necklace. It isn't made with gemstones but rather with beach glass. Randall made [it] for me in 1997. It was from 4 different beaches where we had camped since our son was born. Two in Nova Scotia, one in Prince Edward Island, and one from Vermont. Each of the silver pieces is engraved with the name of the beach where we vacationed. It is very special to me.

The years passed, with Randall’s jewelry business continuing to grow, Mary Lee designing helping customers design their log homes, and Graye going to school and sorting out what he wanted to be when he grew up. With his advanced exposure to mathematics in elementary and high school he realized that he was more attracted to the practical applications of math than to its academic and theoretical dimensions.

He decided to get his post-secondary education at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. He was attracted mainly by its very strong program in computer science, but also possibly by the fact that he was familiar with that beautiful and historic city because for many years the family had been taking their summer vacations on the nearby sand dunes and beaches of picturesque Prince Edward County (AKA, Prince Edward Island, although that leads to confusion with the more famous island known for growing potatoes, Anne of Green Gables, and being Canada’s smallest province.) After getting his degree in computer engineering Graye found employment in Kingston as a software engineer for the fast growing start-up company RateHub.ca.

Meanwhile, back in Vermont Mary Lee was dogged by her old nemesis, the overall business climate. During another economic downturn the log house company had to lay her off, and the next two jobs she found (which were not as satisfying as that designing one had been) also ended when the companies has to close down. Since Graye was now comfortably settled into employment in Kingston, in 2016 despite the challenges that Randall would face in having to rebuild his jewelry business in Canada they decided to sell their farm in Sharon and move to Kingston to be near him.

Unfortunately, Randall died unexpectedly of a massive heart attack within only a few months after they had settled into their new home. However fate sometimes seems to have a way of balancing things out, and it was soon after that big move that Mary Lee was able to get the kind of job that she had always wanted – a salaried position as an interior designer for the La-Z-Boy store in Kingston.

It isn’t just a store that sells one brand of reclining chairs: It is a service-oriented home furnishings store and the job of interior designer is separate from that of the commissioned sales staff. Her role is to assist customers with the functionality and aesthetic choices they face, whether they are choosing a new item to fit into a room or doing a more major make-over or remodeling. She even does free in-home consultations – in fact, that is the way she prefers to work.

In Canada Mary Lee continued to make jigsaw puzzles, both as a hobby and for word-of-mouth customers. She even adapted a storage closet in her apartment to become a compact puzzle workshop. Interior design is not the same as interior decorating; it aims to optimize a space’s functionality as well. I asked Mary Lee to explain how she applied her interior design skills to that project:

I approached this the same way I would approach any interior design project. The first step was to create a scaled drawing of the space and note important aspects of the room which I would need to remember, such as outlets, electrical panels and the HVAC filters on the ceiling. (I use a laser measuring tool so I can easily do this single handed, not like in the olden days when I needed someone to hold the "smart end" of the tape for a room!)

The second step was to transfer these items into my computer. I use a CAD program to create the rough space. There are important parts to this drawing which will affect the function of the space. For example, I need to be able to access the HVAC twice a year to clean the filters. I also need access to the fuse panel and jack for the internet.

The third step was to add the fixed items I needed to have in my studio. I measured all the parts and added them into the mix onto my CAD model. And Ta-Dah!

The goal with my studio had been to create a highly functional space for cutting my puzzles. I needed to contain dust and mess from the entire enterprise into this one space, so dust control and sound mitigation were among my top priorities. Happily-it worked! My neighbors in the apartment building have told me they cannot hear my saw at all!

The Smyth Puzzles years begin

Then came the Covid pandemic. Beginning in March 2020 the La-Z-Boy store had to close completely for about six weeks due to provincial regulations before re-opening under very strict limitations, and then later that year regulations required it to close again for a full three months. Like so many other people Mary Lee found herself both without a job and with a lot of time on her hands when she pretty much had to stay at home because almost everything else was closed down too.

But, as discussed above, at the same time worldwide demand for jigsaw puzzles was soaring. With her five years’ experience at Stave, 25 years as a puzzle-making hobbyist, and a home workshop with professional-grade equipment already in place, and a son who was a professional at designing and managing websites, Mary Lee was in a much better position to start up an online jigsaw puzzle company than other people who were starting from scratch.

Smyth Puzzles was launched online in August 2020. Her primary marketing strategy was still word-of-mouth but now her reach via the internet was world-wide and not just to friends and friends-of-friends.

As if being a full-time interior designer with a side-gig of being a professional puzzle maker isn’t enough, Mary Lee has other interests and hobbies. One is making music. She is a multi-instrumentalist musician and in 2017 she organized a non-auditioned recreational band and singalong group affectionately called Mother Smyth and the Noisemakers that has even attracted retired professional musicians.

I asked her if she ever tried designing and making jewelry when she had been working with her husband. She said no – she has an affinity for working with wood but not with metal. But lately she has been doing beadwork and one of her designs has proven so popular when she gives them to friends and colleagues that she has been getting word-of-mouth customers who want to buy them. She is thinking of starting up another on-line business.

Mary Lee still has fond feelings about those very early years of her puzzle-making journey when she worked at Stave. In fact, she can even claim some credit for the company’s continuing success. They still use some of the whimsy patterns that she designed when she worked there (because keeping a library of whimsy patterns is standard practice for wood puzzle-makers), and one of her elementary school art students, Jennifer Lennox, grew up to become a cutter/designer there and is now the co-owner of the company.

A wonderful article, Bill. Mary Lee is an exceptional puzzle cutter. I have followed her every posting and she has even shared some tips and encouragement with me. A terrific tribute to a very talented and genuinely nice person.

Well done, Bill. Your posting for today is my favourite among all 34 that you've shared regarding your wooden puzzle hobby. As usual, there are things here to be learned about the tools, techniques, marketing, and enjoyment of the puzzles, but your interview/biography of Mary Lee Smyth also includes oodles of human interest and has a stand-alone quality as an engaging piece of writing, whether or not one cares about puzzles per se. Thanks, and best regards, —Greg