7. Viking puzzle from Woodbests

Assembly and review of an inexpensive puzzle from China, thoughts on Chinese-made puzzles, and a very long digression about cowboys, Vikings, and their hats (about 4000 words; 20 pictures)

Laser-cut Woodbests no puzzle designer identified

Artist - not identified

287 pieces 16.5” x 14.2” 3mm 3ply basswood UV printed on wood

Premium wood jigsaw puzzles are expensive, but I’m not complaining about their prices. I know that whether they are hand-cut or laser-cut they are labour-intensive and made from pricy materials. Most of the makers of premium puzzles package them somewhat extravagantly to feature their special status in the world of jigsaw puzzles. (They know that many of the ones they sell will be given as gifts to people who are more used to assembling the far less-expensive cardboard puzzles.) So I am not saying that they are over-priced; just that, for me, living on a bureaucrat’s pension, they are fairly expensive.

So my intention since I first rediscovered jigsaw puzzles in January has been to alternate assembling premium “heirloom quality” puzzles with less expensive alternatives. At first, I expected to alternate with cardboard puzzles but I soon found that there was too much difference in the experience. (Take that as a warning: wooden puzzlers can spoil you from enjoying that lesser alternative!) Now I am fluctuating between premium quality puzzles that I buy new, with used and vintage ones that I find online, and lower-priced new wooden puzzles.

I am not expecting the less-expensive puzzles to live up to the same quality standards as the more expensive premium ones. I expect shortcomings. But I do want an experience of assembly that is enjoyable and approximates a high-quality puzzle with regard to factors that are important to me, like an attractive image, good quality printing and manufacturing, and an enjoyable cutting design.

Chinese wooden jigsaw puzzles and the Woodbest company

Suspiciously inexpensive wooden jigsaw puzzles sold and shipped from China abound on the internet, as do reports of scams, poor quality and shoddy customer service. But even the legitimate Chinese companies operate under a different business model than companies in North America and Europe, and they live under the same dark cloud of suspicion that is created by other Chinese companies that do have shady business practices.

In the Western countries laser-cut wooden jigsaw puzzles are almost always designed and made by the company whose name they are sold under, and small-scale start-up laser puzzle-makers have proliferated since the beginning of the Covid pandemic. These Western companies almost all appear to have begun as small, artisan workshops with one cutting machine, and the founder designs, fabricates and markets these unique products with online sales being their primary outlet. If their businesses are successful they grow and expand, but the company continues to make and sell their own puzzles. Some, like Wentworth in England, Unidragon and DaVICI in Russia, and Liberty, Nautilus and Artifact in the US, have become fairly large companies following this model.

But as far as I can tell, wooden jigsaw puzzles from China are made by a few large manufacturing firms who do not sell their puzzles under their own name. They sell puzzles in wholesale lots, either as pre-designed products from their catalog or made to the retailer’ specifications. These are packaged and labeled generically or in teh same packaging but with the customer’s brand name. Most of the Chinese businesses selling wood puzzles online therefore are simply retailers, not puzzle-makers, and that is why it is so common to see the same Chinese puzzles available under many different brand names.

This is not a shady way to do business. We are accustomed to house brand products in the West for many kinds of products, and in fact this is the way that many well-known cardboard jigsaw puzzle brands (e.g., Cobble Hill) are manufactured.

Wood jigsaw puzzles that are made in China seem to share some characteristics. They are made from lightweight basswood (known as linden or lime in Europe) and they are comparatively thin – two or three millimetres. The ones that are 2mm thick are die-cut, like a cardboard puzzle, and tend to have piece-counts equivalent to cardboard puzzles. Three mm thick Chinese puzzles like this one are laser-cut and their size is indicated using uniquely Chinese standardized categories that range from A1 to A5.

Some Chinese puzzles are loose imitations or direct copies of puzzles from reputable laser-cut puzzle companies. The heavily-advertised Russian company Unidragon is especially prone to having its designs copied, and even to having its brand counterfeited, or to having their distinctive design style for animal pictures imitated by Chinese companies.

As far as I can tell, Woodbests Puzzles does not manufacture the puzzles that they sell. In their Our Story page they claim to do their own cutting designs, but on the back of the box it seems to indicate that the manufacturer is Hunan Liangzi Star Technology Co. (A google search yields no hits for a company by that name.) I have not seen this particular puzzle available from any company other than Woodbests. However I have seen some of the same puzzles that Woodbests sells (same artwork and piece counts) for sale on Amazon and elsewhere by other companies.

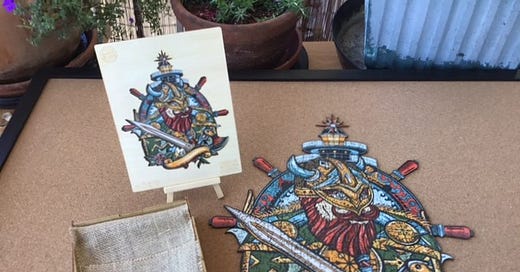

This puzzle and first impressions

I bought this puzzle from the Woodbests website, where all puzzles are always on sale at about 40-50% off their artificial list prices. Four sizes of puzzles with this artwork are available. This 278 piece one is the second largest and its current “sale” price is about $40 USD in “eco-friendly packaging” (i.e., just a cotton bag) or $50 the way I bought it in “wooden gift packaging.” Shipping from China was free with a minimum order of $59 so it is one of two puzzles that I bought in this order. The other was just in its bag. I was somewhat surprised that both came together shipped only in a bubble-wrap envelope, but they both seem to have arrived safely.

The wooden box is attractive with an in-set UV printed picture. It is the same style of box that is used by Unidragon and many Chinese puzzles. There is a small easel to hold the cover for those people who like to use the picture for reference. The cover picture is smallish. It would be useful for referencing the general composition of the puzzle’s image but not for detailed piece-finding. As with all wooden boxes of this type, after its clear plastic-wrap is removed the box only provides safe storage for the pieces if the cover is taped down.

When I poured out the pieces the mild smoky smell was accompanied by some chemical notes, possibly a cleaner. (After the pieces had been out for a few days the aroma was almost completely dissipated.)

The pieces are 3mm thick 3 ply basswood. Technically it is a hardwood, but it is lightweight at about 60% of the density of the birch plywood or medium-density fibreboard that is commonly used in wooden puzzles. This basswood ply does seem to be sufficiently durable (there is only one small chip missing from one of these pieces) but the light weight and 3mm thickness do not live up to the feeling of richness that one gets from premium-quality wood puzzles.

The colours are vibrant and are printed directly onto the wood, which is a feature that I like. Even when sorting the pieces I noticed that the anonymous artist who painted this image chose to use a very limited colour palette. It shows no brushwork, more like a poster, and there is no shading other than that provided by small black dots. The colours are two shades of red, three each of blue, green and orange/yellow, and one each of black, white, brown, grey and beige.

It is during sorting that I discover and enjoy the whimsies. This puzzle has 30 of them. They are well-designed, and a mix of elaborate and rather simple onew, equivalent to many premium puzzles. They mostly suit the theme of the puzzle quite well although it is somewhat of a stretch to include an elephant, lion and butterfly in a Viking puzzle. (I include photos of the whimsies at the end of this preview-essay, under Potential Spoilers.)

A few of the pieces had not been completely cut by the laser and were still held together by some strands of wood fibre. I found that when I tried to wiggle them apart they tended to tear unevenly but they were easy to separate with a bit of help from an X-Acto knife. Also, some of the pieces had laser discolouration on the image side. I have also found this occasionally on premium puzzles. It is smoke residue and can be cleaned off with rubbing alcohol and a Q-tip. (For more information about this smudging see my comments near the end of this review-essay.)

Assembly

As usual, I set out to assemble this puzzle without using the reference image. My recollection of the artwork was very limited: I only remembered that it had an irregular edge and was a Viking warrior – the familiar inaccurate kind with horns on his helmet – and that he was surrounded by other stuff that didn’t make much sense.

Since the puzzle has an irregular edge I began with targets of opportunity and by using colour to consolidate pieces into islands.

Even after the puzzle is complete I still don’t know what that thing in the upper left that looks like a modern air traffic control tower is supposed to be.

I did recognize the sword and ax head. The varying sizes of the black dots used for shading on the white sword proved to be quite useful in that part of the assembly. The shading dots on the coloured pieces were not as useful.

At this stage I still had no idea which sides of my growing islands of pieces were up or down. I did guess, correctly as it turns out, that the “traffic control tower” would be at the top of the image, and that the sword would be near the bottom. I considered referring to the box cover picture to get a general orientation but decided to stick with no-peek, more out of stubbornness than anything else.

Also at about this stage I realized that although I could make very little sense from the details of the image and that whatever I know about the Vikings would be of little help with assembly since the image incorporates elements and design details that do not seem to relate to the Vikings or Norse culture (like Celtic knotwork on a Viking ax blade.)

However, I was growing increasingly engaged with the puzzle and appreciative of the quality of the cutting design. This is indeed a tricky puzzle, and I was both being challenged and having fun during the assembly.

I should have realized much earlier than I did that since this is a cartoon stereotype of a Viking warrior the rest of the red pieces would be his beard …

… and that the beige pieces would be his face.

To avoid it being a spoiler for some, the backview is available at the end of this essay-review.

Review

This new puzzle costs about half the price of a similar-sized North American puzzle, and the shipping was slow but free. I can’t assess whether getting it in a cloth bag packaged in a bubble-wrap pouch would provide sufficient protection for international shipping, but if so, this puzzle can be bought new for $39 (USD) delivered. The “wooden gift box” packaging is attractive and provided good protection for the initial shipping, but it needs to be securely taped shut for safe storage. I appreciate that the company only charges $10 USD for it over the simple cloth bag.

The 3mm thick pieces are much less luxurious than the 5 and 6 mm that is standard for most North American puzzles, and because the puzzle is made from lightweight basswood they are not even as tactilely satisfying as other 3mm puzzles such as those made by Wentworth and Unidragon. On the other hand, basswood does seem to be tough and durable and I expect that the puzzle will not be damaged by repeated assembly if normal care is taken.

I was very pleased by the design and quality of the cutting. All of the pieces were within the same size range and none of them had places that seemed particularly susceptible to breakage. The appearance and intricacy of the whimsies is equivalent or better than most brands. As is typical, the non-whimsy pieces are mostly interlocking. With its irregular edge as a bonus feature I would rate the cutting as being up to the standard of premium brands that I have assembled.

I think of this puzzle’s weak point as being its image, and for that I need to take partial responsibility since I saw it before I bought it. I was attracted by its bright colours, irregular edge, and its unusual subject. In retrospect, perhaps I should have studied the design closer to notice how many of the picture’s elements don’t appeal to me.

As it turns out, the face, helmet and weapons are the only parts of the image that convey Vikingness, and the flat texture-less colours give them it a cartoon-like look. The face has one pop-out eye and the other is barely visible. And, of course, he his wearing a helmet with horns.

[Very long digression on Cowboys, Vikings, and their hats: Many years ago I visited the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles. Texas-born Gene Autry had made a very successful Hollywood career starring in cowboy movies. Those were all set in a mythic version of Americans’ pioneer settlement of the western prairies and he became interested in the real history of that region. He established and endowed the Autry Museum to educate people about both that region’s real history over the relatively short time-span of about 50 years beginning with the end of the Civil War, as well as about the romantic, legendary version of that time period of which we are all familiar (or, at least, it is familiar to anyone like me who grew up when Westerns were one of the most popular genres of movie and TV fare.)

The Hollywood version of cowboys and life on the frontier was first shaped by contemporary 19th century sensationalistic journalism and cheap literature that purported to depict an adventurous life on the then-contemporary frontier, and by later depictions based on those sources in movies and television.

The Museum effectively shows that what really happened was quite different from the “Old West” that I had grown up watching on the screen, and understanding real history is important. But because the myth is so powerful and enduring, it too is important and worth understanding. Its depiction of the a world where (usually without any support from government institutions) the iconic cowboy “good guys” in white hats inevitably eventually triumph against long odds over the black-hatted bad guys is more than a metaphor: It has become a key part of the collective American self-image. That might have been the most educational visit to a museum that I have ever had.

Did you know that the style of hat that we now universally associate with cowboys was worn by very few actual nineteenth century cowboys? That image primarily comes from illustrators, and later, movie costume designers. It is based on a 4”brimmed beaver-fur felt hat (nicknamed with considerable exaggeration the “10 gallon hat”) that J.B. Stetson introduced in 1865, customized with its crown creased and the sides of its brim gently rolled up.

It was a very good hat, popular but very expensive, that would have been worn by prosperous ranch owners and farmers. But the actual cowboys that they hired would have been much more likely to wear an old top hat (that had gone seriously out of fashion by that time), a bowler, a military hat of various styles, a slouch or flat hat, a sombrero, or a brimmed straw sailor hat.

Very few real cowboys on the frontier could afford even the cheapest model of Stetson hat. But that is the western hat that prosperous early American and European tourists (brought west on the expanding railways) bought and brought home with them, and thus the one that Eastern-based illustrators and costumers chose as headgear for their iconic cowboys. Over time, rather like Pinocchio turning into a “real boy”, Westerners made that iconic headgear a part of their real self-identity.

A similar thing happened to the Vikings and their headgear. “Viking” is a word that developed in the 18th century to depict Scandinavian seafaring explorers and warriors from the late 8th to the 11th century. During that time warriors from Nordic coungtries raided and pillaged from other lands (prosperous monasteries were a favourite target), and they led expansion from their homelands to settle lands that they conquered or discovered. In Europe these Viking settlement lands include much of the British Isles, Ireland, Normandy, parts of modern-day Russia and Ukraine, and Iceland.

The word Viking is now sometimes used to refer to all of the Norse people during that relatively brief exploration and expansion period of less than 300 years. They generally lived a pastoral lifestyle and developed art and culture that is arguably more “civilized” then that of Christian Europe at that time. But as with the American Wild West, the image that springs to mind when we hear the word Viking is of the warriors, even though that isn’t an accurate image of the people as a whole.

The Vikings did not write their own history. In their time period accounts of their raids and conquests were written about by the Christians who feared and hated them. Monks and other survivors of Viking raids, and later, traders and travellers who encountered in their old and new homelands wrote about them in … well, shall we say “unflattering terms”. But they didn’t draw their portraits, and when they did make images of them they never had helmets with horns.

Some old helmets with horns have been found by early archeologists, but we now know that those artifacts actually date back to Bronze Age times, over 1000 years before the Viking era. But in 1875 those finds influenced German costume designer Carl Emil Doepler to include a few horned helmets in his designs for the large cast of ancient Norse warriors needed for the premier performance of Richard Wagner’s cycle of operas Der Ring des Nibelungen.

Wagner’s operas had been based on stories from Nordic and German folklore, and were meant to elicit German pride in their Aryan racial heritage. Although most of the warriors’ helmets featured different decorations, the most common being wings, for some reason it was the horned helmets that most captured the public’s imagination when the opera’s opening sparked an infatuation with all things Viking.

At the time, the concept of an Aryan race was the now-discredited theory that the early people of Northern Europe (who spoke the proto-Indo-European language) was distinct from Greco-Roman cultural heritage of other Europeans. Doepler chose to clothe the cast in a fantasy version of early, exotic Iron-age armour. Images of his elaborate costumes “went viral” at the same time as “cowboys and Indians” portrayal of the American West was sparking European interest in their own heritage of native peoples, and the Vikings were being reinvented as a glamourous indigenous aspect of their own past.

Although Doepler’s costumes were meant to depict warriors from long before the brief Viking era, other illustrators and the general public did not make that fine distinction. Late 19th century Viking-mania spread out of Europe and to North America and images of horned Vikings began to appear everywhere. Within 20 years, images of Vikings nearly always had them wearing horned helmets and they have now become as indelible as cowboy hats.

The Washington Post’s art critic Philip Kennicott calls Viking horned helmets a Zombie Cultural Symbol for both Vikings and opera in general. But, as with the American Old West, besides the objective Truth of what happened, our enduring acceptance of the known-to-be-wrong mythic image might be meaningful in itself. As Yale Professor Roberta Frank, who wrote a scholarly essay on this subject, noted: “However ‘wrong,’ the horned Viking helmet has been a recurrent fantasy transmuting the desert of daily existence into contours rare and strange.”

If you want to learn more about the history of Viking horned helmets I suggest this or this article as places to begin, or this scholarly essay by Prof Roberta Frank. This article and this one dispel other commonly-accepted myths about Vikings.

End of very long digression.]

In the puzzle image, at least the white horizontal things on either side of the face which appear to be stylized fish-bones do accurately Viking life. But other aspects of the image that appear intended to convey Viking heritage also are historically inaccurate. For example, the geometric fish-shaped symbol on the character’s helmet looks like a letter from the Norse runic alphabet, but isn’t an authentic one. Also, the red-coloured old-fashioned radio vacuum tubes turn out to be handles on a ship’s wheel. But all Viking longboats had a side rudder: Ship’s wheels weren’t invented until about 1700 (and radio vacuum tubes weren’t invented until 1904.)

The design on the three circular objects that appear to be shields appear to be a real mystical Norse symbol, but such a fine-detailed design would never have been found on a battle shield, let alone on three of them. And I still have no idea why an air traffic control tower appears in the image. (Because Vikings were world travelers?)

Most of the other shapes and patterns appear not to have any intended Viking meaning. They are filler, much like the random shapes and patterns that are used in the colourful, stylized animal pictures that have become such a popular motif for laser-cut wooden jigsaw puzzles, especially those from China. Once I realized that, I realized this puzzle image isn’t really intended to depict a Viking, or even the stereotype of one. It is a stylized abstraction made to become a Chinese-style jigsaw puzzle.

On balance, except for not particularly liking the image (which I take responsibility for since I chosen to buy it after seeing the picture) assembling this puzzle was a very satisfactory experience, and in fact it exceeds my expectations for a puzzle of this price. Of course it isn’t as fulfilling as assembling a good $100+ puzzle, but it did give me several hours of enjoyable puzzling that was worth its $50 price tag.

This is the second Woodbests puzzle that I have bought and assembled and fortunately I have had no need to test their customer service. The (free!) delivery is slow, but both of my orders arrived safely. But there is no shortage of unfavourable reviews of this company online, so I am hesitant to say that I recommend buying their puzzles. However I do expect to buy further puzzles from them myself, but I will pay closer attention when choosing the image.

Potential spoiler pictures

Below are photos of the backside of the assembled puzzle and close-ups of its whimsies.

keep going

In my opinion, this is your best write-up so far, even though you are presenting a puzzle with a few disappointing features. I enjoyed the detailed description of how you chose, ordered, cleaned up, assembled, and assessed this Viking puzzle. Coincidentally, I wrote a short piece of creative writing yesterday on a Viking theme for my recreational writers' group. Thanks again for the research you do and share, Bill.

My biggest quibble with whimsies is when they have no relation to the image -- like the parrot 😹 But I think that your "Air Traffic Control Tower" is a lighthouse, although same issue as the ship's wheel not being relevant to the era! I liked reading about the myth of the American West, and how it has just as much weight in shaping American cultural identity as what the West was really like. I'd say that if one wanted to get a good idea about what moving out the to the "untamed" wilderness was, the Little House on the Prairie books are a great intro to at least one side of the story!