51. The final puzzle in this Wentworth binge: The Pull

This one depicts a famous rescue performed by a Whitby lifeboat in 1881. This posting about my research is (mercifully!) much shorter than last time (about 2300 words; 19 pictures)

This is the second of two postings about puzzles that feature images of 19th century British lifeboats, and my write-up primarily reports on my research into the rescue that the image depicts. The first posting includes more lifeboat rescue stories as well as a fairly in-depth essay about early lifeboat history.

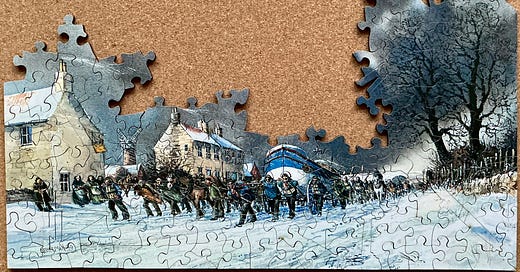

The puzzle

This puzzle came up at auction while I was doing my extensive research for Nightime Launch of the Zetland Lifeboat from Redcar Beach. It portrays an epic 19th century rescue by a Whitby lifeboat crew, with an image painted John Freeman, the same artist who painted the image for the Zetland puzzle.

I knew right away that it would make a great companion for that other newsletter/blog entry and so I didn’t study the cutting design or the image much before bidding for it. But even a quick glance registered that this image would not give anywhere near as many assembly clues as I had gotten from Zetland. I really wanted it so I bid more than I knew it would go for. As it turns out I was the only person who bid for it so, as with Zetland, I was thrilled that I got it for its opening price of £10. (The list price for new 250 piece Wentworth puzzles is £33.)

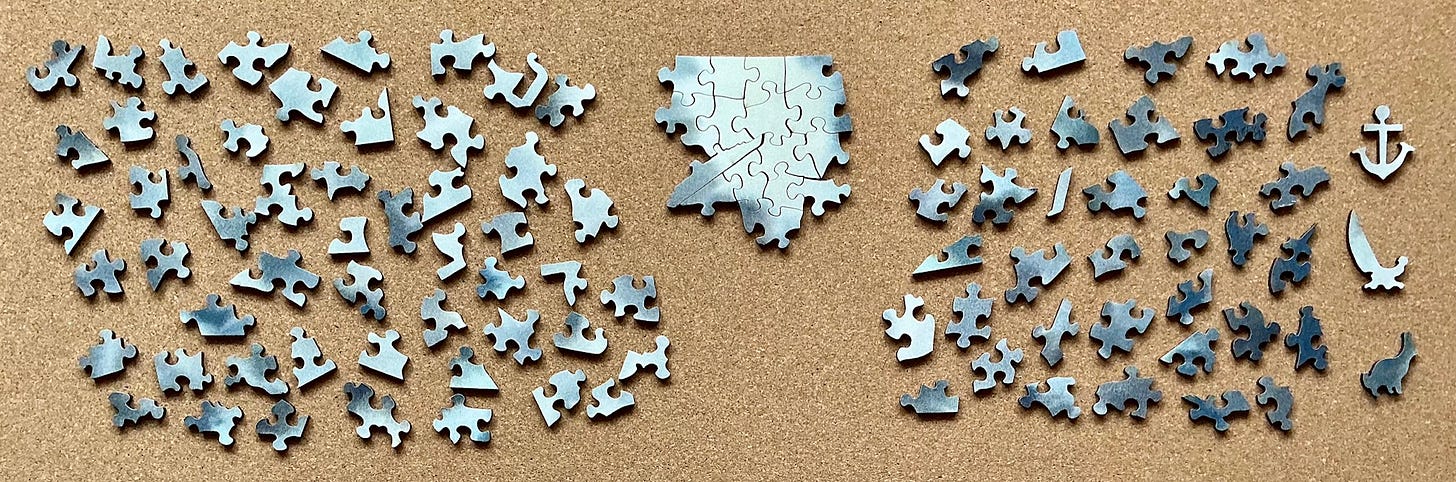

After it arrived I toyed with the idea of saving the figure pieces for last, but as I flipped and sorted the pieces I could see that my quick impression had been correct about the image not being generous with clues. Well over half of the pieces seemed to be various shades of either grey or white, and most of those were either plain or had a slow gradient from one shade to another. I gave up on the idea of saving the whimsy pieces for last. I enjoy a challenging puzzle but there is no reason to be masochistic about it.

In the first assembly photo, below, the light coloured ones on the lower right have the artist’s signature, which is always helpful for a quick start. The upper right is the prow of the lifeboat and those are the only pieces that include bright blue. The large assembly of a building pieces have a peculiar shade of yellow-grey, and the small two-piece sub-assemblies ones just popped out for me.

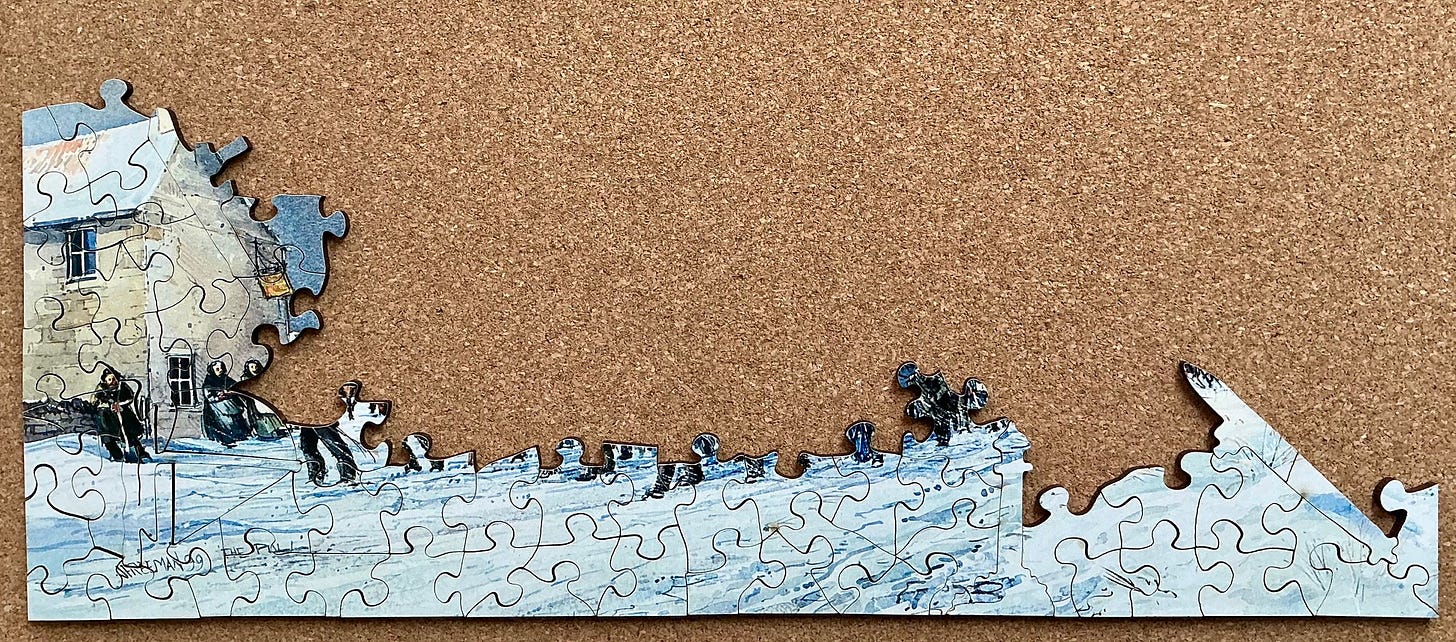

I continued with the white and blue pieces that were obviously wind-swept fallen snow:

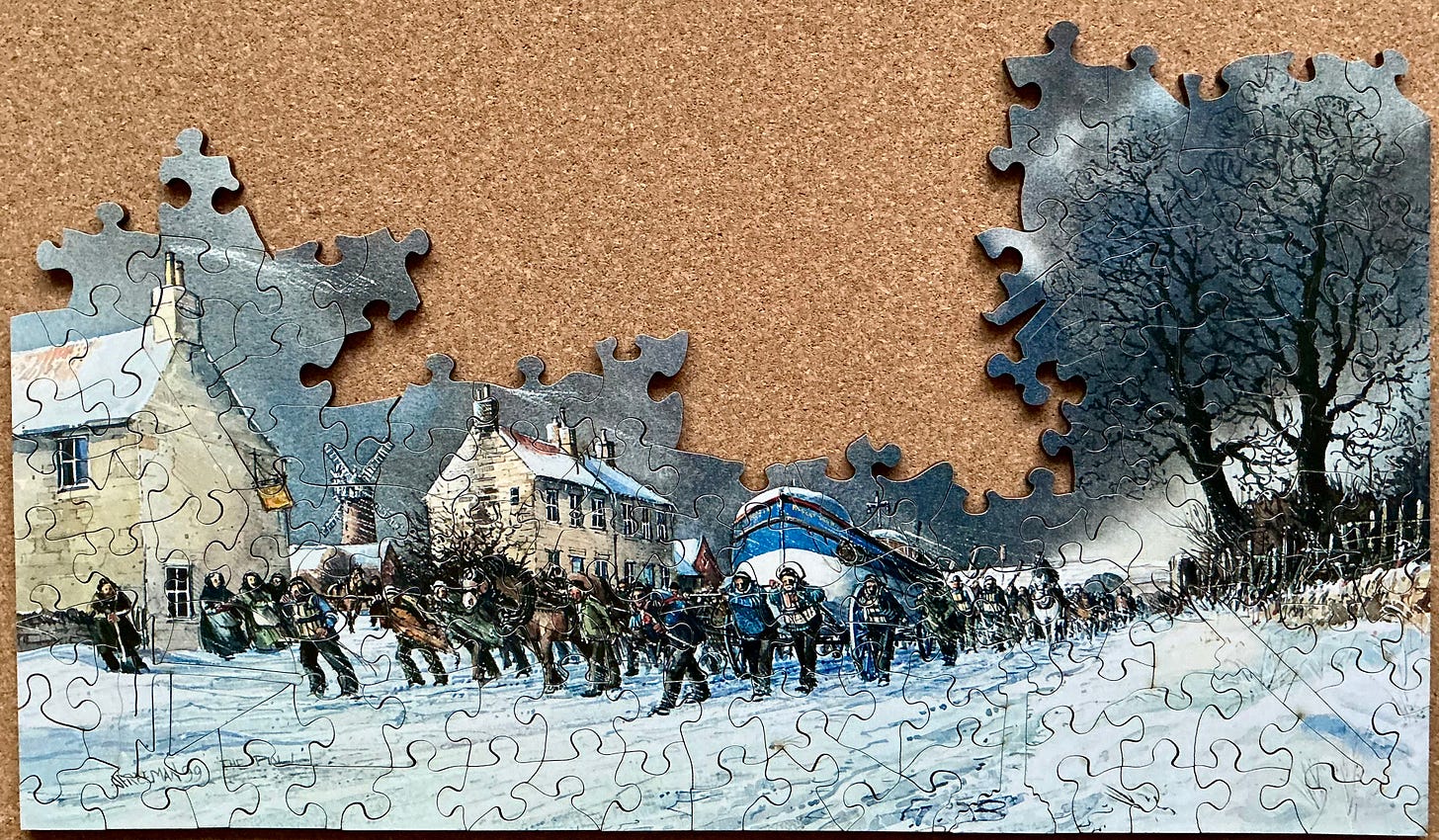

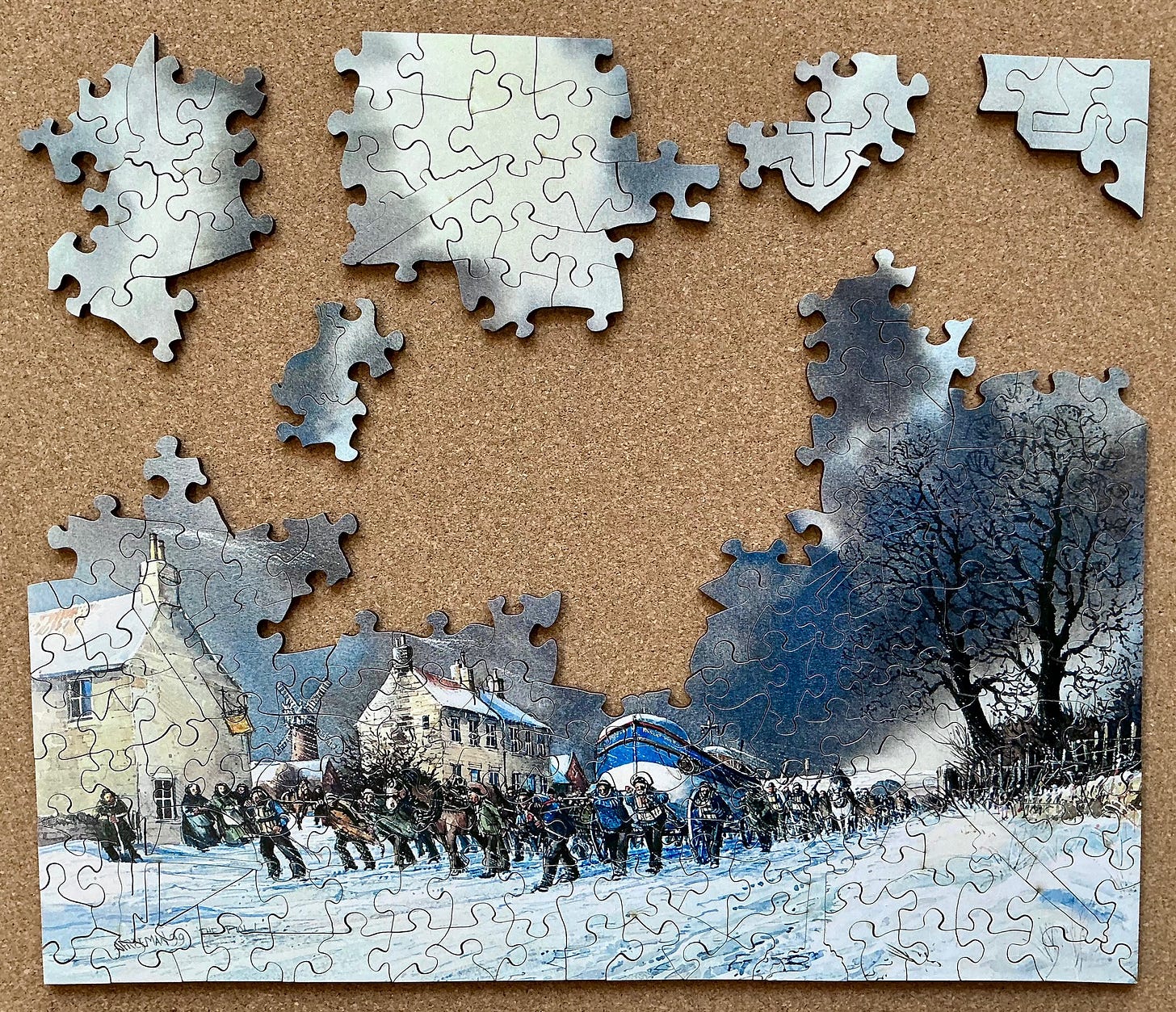

Then I moved on to add the pieces with people. Now I had the image’s focus of attention:

I continued the build by working on the frontier of what I had already assembled. A number of the remaining loose pieces had some black texture to them that would obviously be the bare branches of the trees on the right side of the painting. I brought them all together for the next stage of assembly:

That enabled me to place all of the pieces that relate to what was happening on the ground.

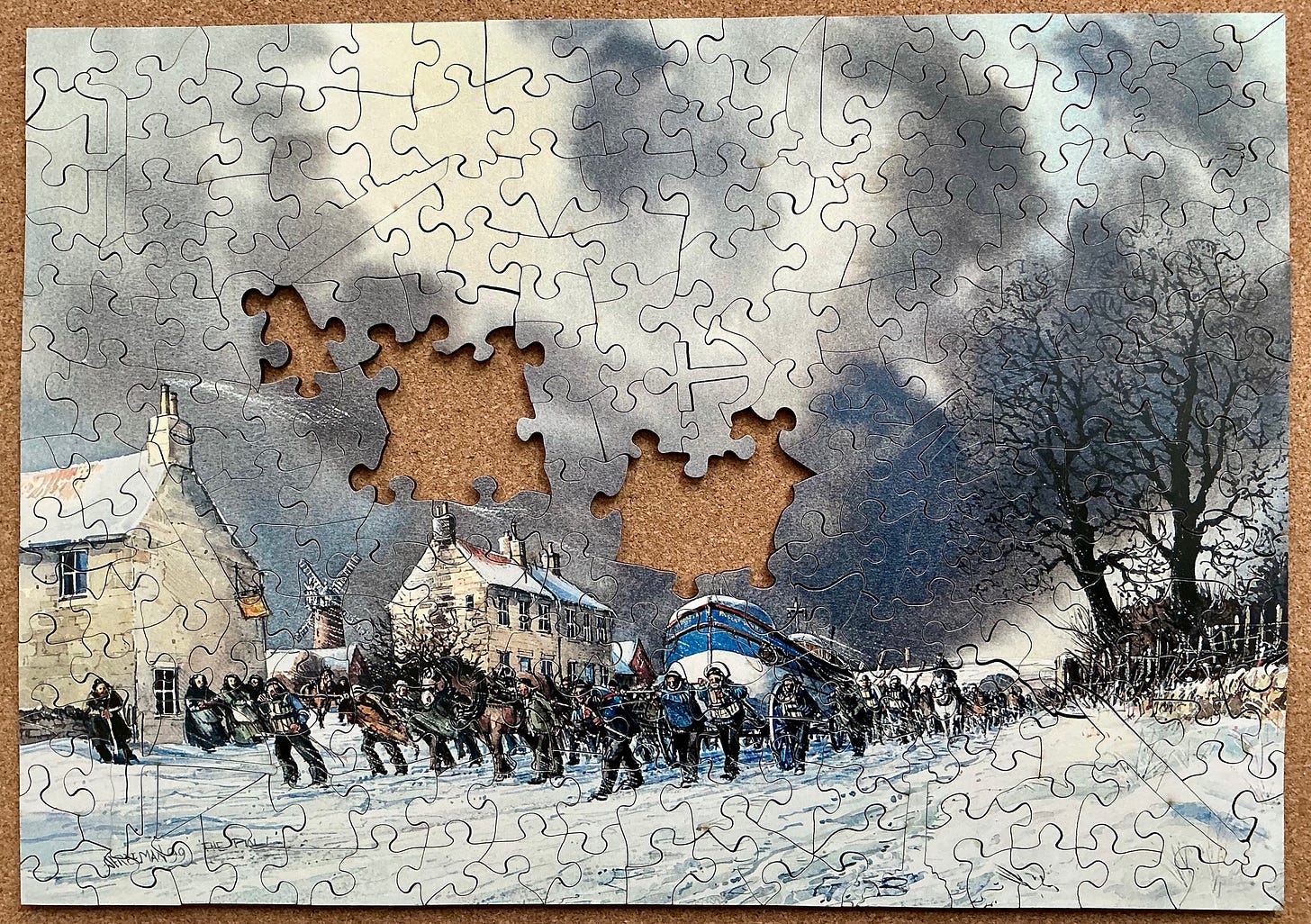

But there was still a lot of sky left to do. They were just various shades ranging from grayish-white to blackish-gray, with many that had gradients between shades. I began with the grayish-white ones and moved on from there:

The figure pieces in this puzzle are all nautical (except for one rabbit-like critter) so this assortment is fairly typical of what passes for having thematic figure pieces in a Wentworth puzzle. But actually, only the lighthouse, anchor, and the fellow with semaphore flags relate to a 19th century lifeboat. (By the way, it might be just a coincidence but the lobster trying to catch a (toy?) submarine is how their whimsies are placed in the cutting design. In my experience, having figure pieces in Wentworth puzzles spatially relate to each other is quite rare.)

The rescue

In January 1881, beginning on January 15 a particularly strong gale coming down from the Arctic began pounding all of England producing a ferocious blizzard. Before long, most of the country’s trains could not travel because of snow drifts that were up to eight feet deep. In London it caused an estimated £2 million damage, including the destruction of 100 boats and barges. In Yarmouth seven ships were wrecked, with 50 sailors lost including six lifeboatmen. It was like that all over the country.

Three days later the wind shifted to the southeast. The snow stopped falling from the sky, but the wind was still blowing strong. A drama was taking place off the Ravenscar headland near Robin Hood’s Bay south of Whitby, known locally simply as Bay.

There are local legends, but no evidence, that Robin Hood himself (if there ever was such a person) had ever lived in that isolated coastal town but the fishing village had been settled long enough for that to have been the case. And it is just the sort of town where the Nottingham outlaw might have felt safe.

In the 18th century Bay was famous for being Yorkshire’s most notorious hotbed for smuggling and even piracy. It was isolated on the land side by difficult travel across a moor and from the sea by dangerous rocks. Even press gangs and the coastguard were afraid to go there: The Bay men were at least as well-armed ready-to-fight as they were, and its women would pour boiling water down on them in the narrow winding streets.

But back to the story of the 1881 drama in the nearby waters: An elderly collier brig with its sails torn to shreds was being driven towards the treacherous shallows. Its hull was damaged and the ship was taking on water much faster than the sailors could pump it out. I’ll let Jane Ellis of the North Yorkshire Moors Association tell some of the story (lightly edited):

In the middle of the night she was taking on so much water that the master set down the anchor, hoping to ride out the storm. The wind veered north-easterly bringing snow and hail, and sea conditions were atrocious. Waves were breaking over the deck and the crew of six attempted to save themselves by taking to the ship’s boat, but dared not leave the comparative shelter of what was by now a wreck for fear of being driven onto the unforgiving rocks beneath the cliff. Dodd, the apprentice, was wet through and frozen, having jumped into the sea and swum to the boat roped to a buoy, to be pulled into it by the other crewmen, and here they spent the bitter winter night in conditions beyond imagination.

It was only when the brig’s quarter-board was found on the beach at Robin Hood’s Bay the next morning that anyone realised there was a shipwreck. The six men in their life-threatening predicament could just be seen from land two miles to the south of the village.

The Bay lifeboat was old and the local fishermen who were its crew regarded it as unseaworthy for launching into such mountainous seas, a decision confirmed by the coastguards who had inspected it [when the lifeboat station had been closed down 25 years earlier.] In desperation the Vicar, Revd. Jermyn Cooper, sent a telegram to Whitby: “Vessel sunk, crew in open boat riding by the wreck, send Whitby lifeboat if practicable”.

Rowing the lifeboat, the Robert Whitworth, around the coast from Whitby in such conditions was out of the question, but the Whitby branch secretary of the Royal Naval Lifeboat Institution (RNLI), Captain Gibson, along with first and second coxswains Henry Freeman and John Storr, took the momentous decision to haul the boat the six miles to Bay overland.

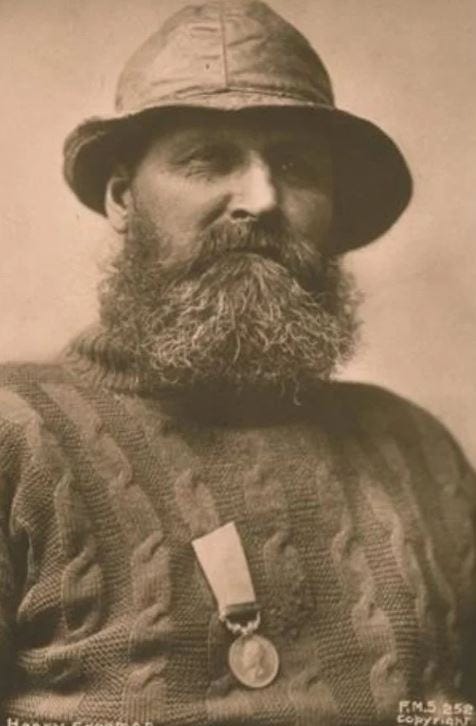

Local legend has it that it was coxswain Henry Freeman who first suggested hauling the lifeboat overland to Bay and launching from there. I don’t know if that had ever been done before. Freeman was already recognized as a lifeboat hero having earned an RNLI silver medal twenty years earlier when as a rookie lifeboatman on his first day of call-out he had participated in three successful rescues, and on a fourth attempt he was the sole survivor when a huge wave struck the lifeboat throwing everyone overboard. He survived because only he was wearing one of the newly-invented cork lifejackets.

The previous year Freeman had been awarded a silver clasp for his silver medal: He had coxed the Robert Whitworth when it made four successful rescues on the same day under weather conditions that were very similar to the 1861 tragedy. But earlier during that same 1881 storm he and his crewmates were involved in another tragedy when they were one of two lifeboats that were sent out during the night to rescue the sailors from the foundering collier brig Lumley.

The Robert Whitworth was the second boat to be sent out on that mission but he and the other crewmen misinterpreted the extinguishing of the red distress signal light from the ship and the lighting of the blue light at the lifeboat station as meaning that the sailors had been rescued by the other lifeboat, and accordingly they returned to their station. The blue light did indeed mean that the lifeboat had returned to the station but in this case it did not mean that they had been successful. All of the Lumley sailors drowned and Freeman felt responsible for their failure to effect a rescue. Perhaps he saw this as a redemption opportunity for himself and the Robert Whitworth crew.

The first part of the overland route they took to Robin Hood’s Bay was along the Scarborough road to the village of Hawsker, which is about halfway there and at an elevation of 500 feet (over 150 metres) above sea level. Volunteers from that town joined in helping the effort, and meanwhile residents from Bay were clearing a path up from their village to the approaching lifeboat. Outriders from both towns enlisted aid from farmers who lived on the moor.

After passing through Hawsker the road heads inland, so from there the tow had to be cross-country down from the moor and into the howling wind. Besides pulling, pushing and shoveling, rock walls and hedges had to be removed to clear a path. It is estimated that all told nearly 1000 people participated in helping to bring the lifeboat from Whitby to Bay. Remarkably, the six mile move took only about three hours.

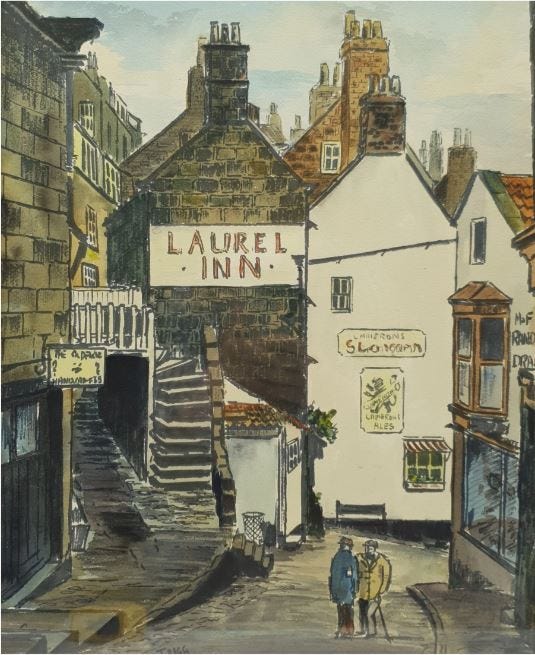

The puzzle’s image depicts bringing the boat over the windswept ridge at Hawsker, which explains the windmill and the relative absence of snow on the ground. Here is John Freeman’s painting without the puzzle cut-lines:

Controlling the descent was probably more difficult than pulling the boat up the hill since I don’t suppose that horses are much use for that kind of work. I have not been able to find any information online about how much such a lifeboat and its carriage and gear would have weighed, but 3-4 tons is probably in the general ballpark.

The road into Robin Hood’s Bay is famous nationwide for how steep it is – a 30% grade!

Now back to Jane Ellis’ telling of the story:

The way down the steep and twisting road was difficult and dangerous. Many helpers controlled the descent from behind by means of ropes attached to the boat’s carriage. At the Laurel Inn there is a double bend that they were barely able to get around with only an inch and a half to spare.

The lifeboat was launched successfully, albeit with some difficulty, however before the wreck could be reached, six of the rowing oars [and one of the sweeps] were snapped by one tremendous wave and the lifeboat had to return to shore.

Some of the oarsmen were by then too exhausted to row, but following an appeal made by coxswain Henry Freeman for volunteers, the boat’s second attempt - now with a larger crew [of 18 men] and using oars from the old Bay lifeboat - was successful.

It was only when they got close to the wreck that the Robert Whitworth lifeboatmen were able to identify the vessel whose crew they were saving. It was the Visiter – whose home port was Whitby. No one had known before that time that the men they were working so hard to save were their own neighbours.

The shipwrecked men were suffering badly from exposure, two of them by now delirious, but with the sea still raging all were somehow manhandled into the lifeboat. The dramatic rescue was completed by mid-afternoon on the Wednesday and thankfully all six unfortunate men escaped with their lives.

Several days later, the storm having abated, the lifeboat crew walked the six miles from Whitby back to Robin Hood’s Bay and rowed the Robert Whitworth around the coast back to Whitby harbour.

I found many versions of this story online. According to this 1:18 RNLI video it is “one of the most outstanding launches in lifeboat history.” Naturally, it has special meaning for folks in Whitby, and since artist John Freeman lives there he has depicted its dramatic events in two paintings. He calls the other one The Rescue and it shows the Robert Whitworth being brought onto the beach from the town’s narrow streets:

Coming up:

This concludes my Wentworth binge. I have a couple of write-ups in the works but I don’t know which one I will have ready to post first but either way that won’t be until a few weeks from now.

Well written, Bill. I can sense your excitement over being able to locate, bid on, and acquire a puzzle and background story that go together so well with your last posting about these very special boats involved in the history of maritime rescues. It's also really appropriate that the work of the very same artist forges a link between the puzzles you've featured today and last time. I further appreciate how the rescue in January 1881 has engaging, stand-alone quality.

Thank you,

Greg Skala