49. Wentworth puzzle binge #4: Zetland lifeboat at Redcar:

The puzzle image is the launching of an historic rescue lifeboat. Almost all of this rather long write-up is about the history behind that small vessel. (about 7400 words; 28 pictures)

[Note: The term “lifeboat” initially meant rowed land-based rescue boats for rescuing shipwrecked sailors and that is how I use it in this essay. Specialized shipboard craft to enable sinking ships to be abandoned were not developed until well after the time period of this story. In fact, the Titanic was one of the first vessels to have them.]

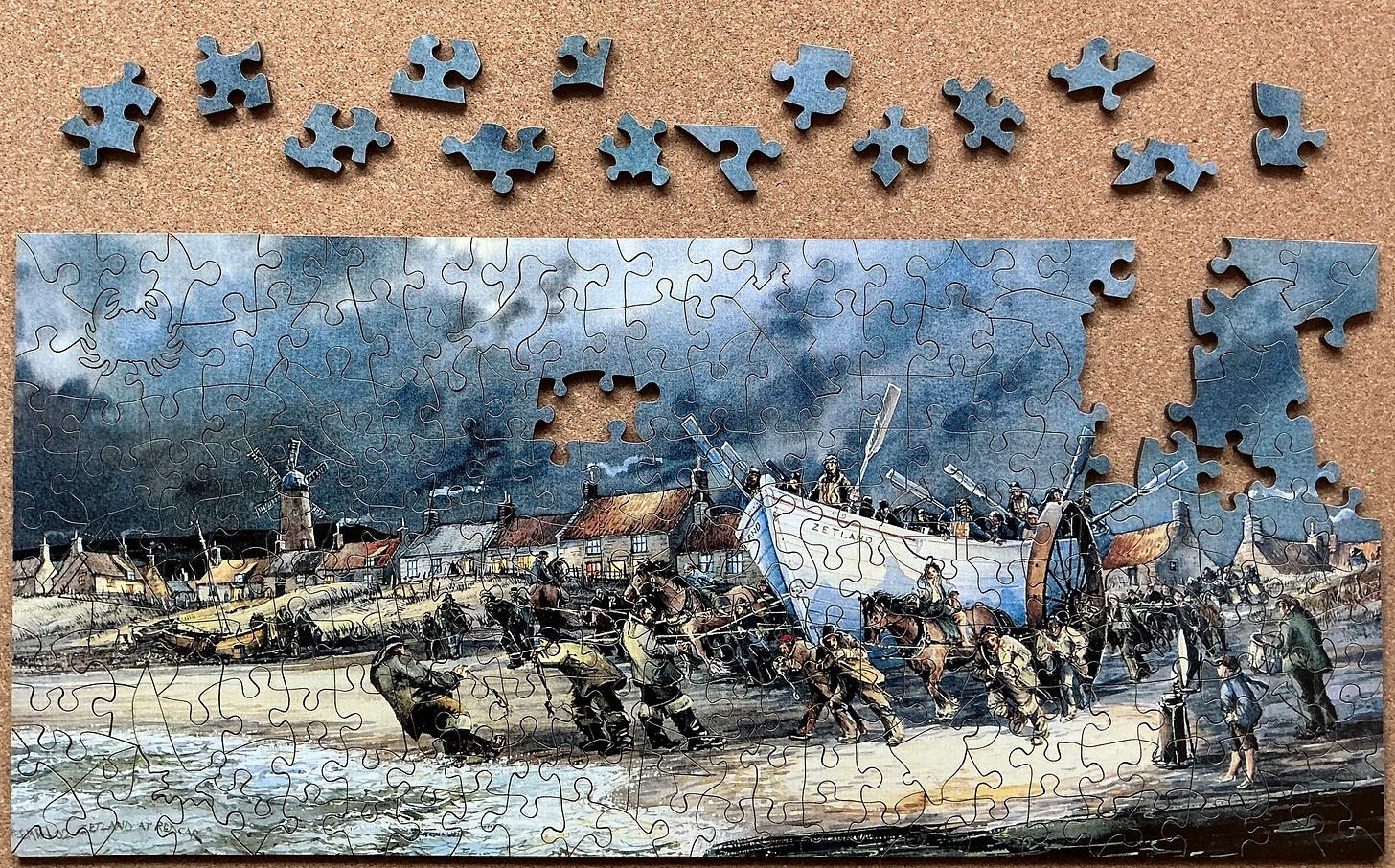

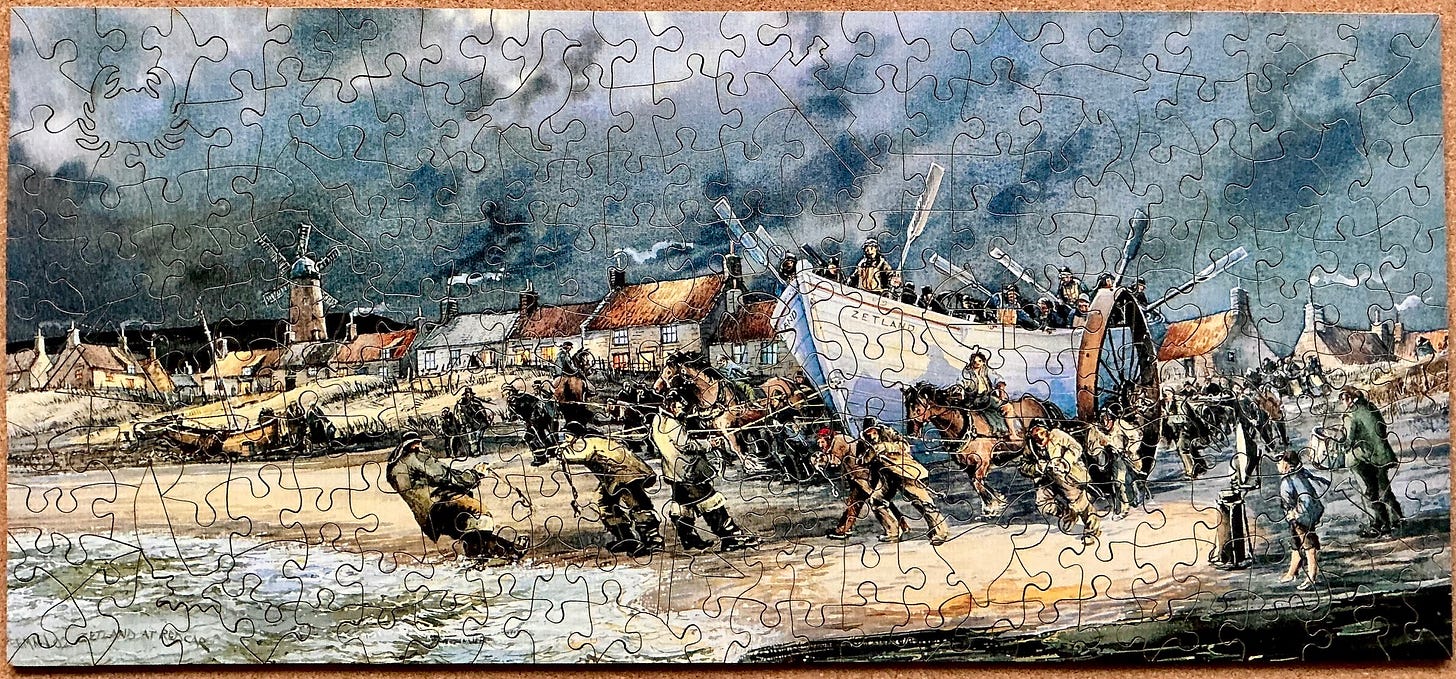

The image

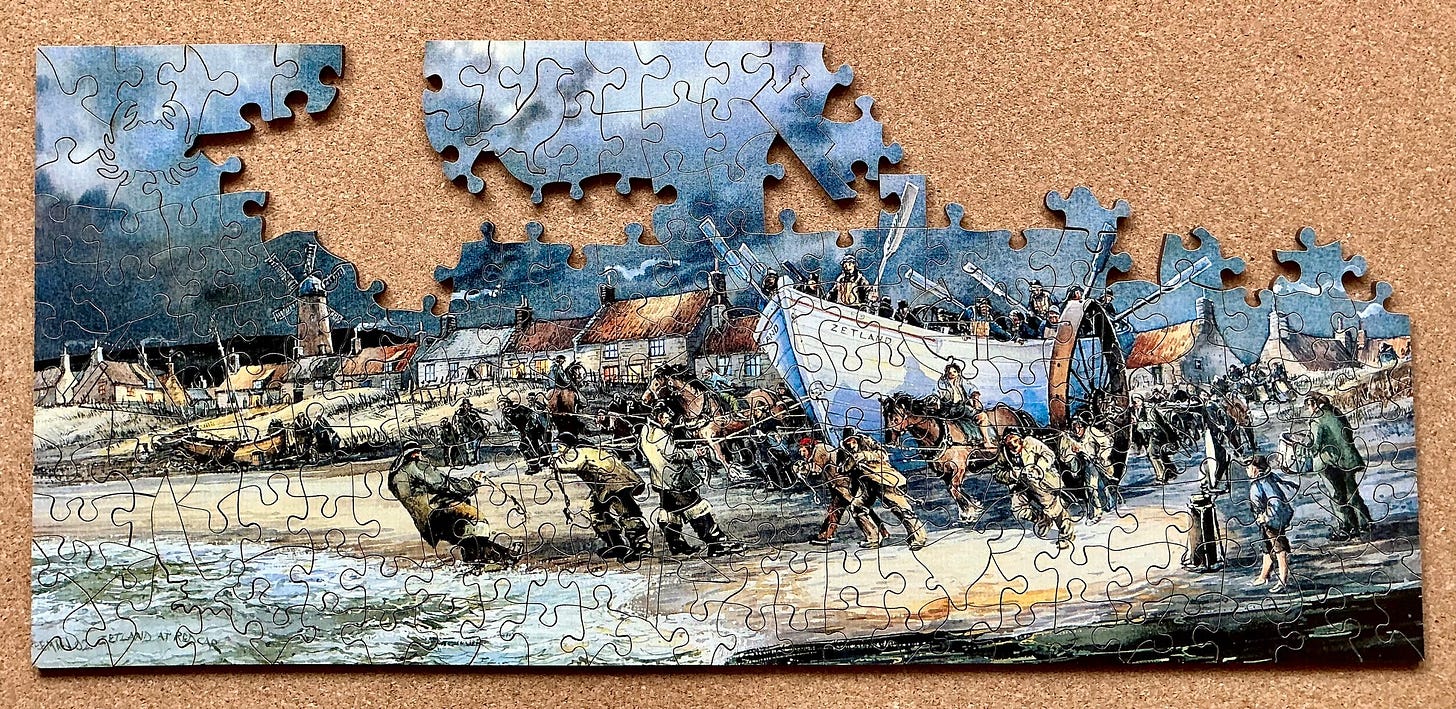

The image for this puzzle was painted in 2002 by John Freeman, who specializes in watercolour paintings of North Yorkshire scenes and landscapes. He lives in Whitby, about 25 miles (40 kilometres) down the coast from Redcar, the village where the events depicted on this puzzle took place. Freeman is especially known for nautical paintings and what he calls nocturnes – nighttime scenes with dramatic skyscapes.

John Freeman titled his painting Zetland at Redcar but Wentworth chose to give their puzzle the ungainly name Nightime launch of the Zetland Lifeboat from Redcar Beach. Actually, the puzzle is only the bottom half of the painting’s full image, a print of which is on display at the volunteer-run Zetland Lifeboat Museum in Redcar:

The reason that the Zetland lifeboat has its own museum is that it is the last remaining example of the first purpose-built lifeboats in the world. They were designed and built at the turn of the 19th century by Henry Francis Greathead a full generation before the founding of Britain’s Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI.)

The invention of lifeboats

The use of fishing boats to attempt to rescue people from shipwrecks is probably as old as shipping vessels themselves. The earliest documented attempt is from the third century BCE when Hunan fishermen unsuccessfully tried to rescue the aristocratic Chinese poet Qu Yuan. In fact, the dragon boat races that are still held today are reenactments of that event. But attempts to design and build specialized boats for that purpose are much more recent and were led by Britain.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries the topic of shipwrecks was all the rage in England, with the newly-created medium of newspapers leading the way by carrying stories about the tragic maritime events and editorializing about the need to prevent unnecessary loss of life. (That was long before the phrase “if it bleeds, it leads” had been coined but the concept was already in place.) Stories of tragedy and heroic feats of bravery sold newspapers.

In parallel with campaigns to build lighthouses and breakwaters, national acclaim was given to inventors of such anti-drowning devices as cork lifebuoys and lifejackets. Inventors were also developing ingenious mortars and rockets that could shoot lines out to shipwrecks that were close to the shore: The shipwrecked sailors could then pull on the line to bring them a special lifebuoy (breeches buoy) and ropes. The rope could be tied to the ship and stretched tight so that the sailors could safely be brought to the shore.

Various coastal communities in locations where shipwrecks were common established coast guards and response organizations, either rocket or lifeboat stations, that operated similarly to volunteer fire departments. They enabled the local people to “do their bit” by attempting to save the lives of shipwrecked sailors.

The need for one item was well-recognized – a specialized rescue “lifeboat.” A suitable design had not yet been invented, but they already had that name chosen for that science-fiction-like specialized piece of gear. Lots of ideas were being floated around (sorry about the pun!) about what features such a craft should ideally have, but in the meantime the best crafts available for the purpose were the swift and sturdy rowboats designed for chasing and hunting whales.

Because shipwrecks were such big news in those days, on a stormy Sunday in 1789 word spread quickly in Newcastle when the coal brig Adventure ran aground on offshore rocks in nearby South Shields at the mouth of the River Tyne. Literally thousands of excursionists came to South Shields hoping to watch a dramatic rescue but they got more real-life drama than they wanted. The local fishermen could not come to the sailors’ aide because their lightweight fishing cobles were not safe for being launched into the fierce wind and crashing waves. They too could only watch helplessly from shore when five members of the Adventure’s crew jumped into the water from the disintegrating ship and drowned.

The disaster inspired a group of South Shields businessmen to sponsor the establishment of a lifeboat station to rescue people from the collier shipwrecks that were all too frequent off their town. They would need a rescue boat. In 1790 they offered a reward of 2 guineas for the design for a boat suitable for their needs. One of their specifications was that the boat should be capable of being righted if it were to capsize.

William Greathead was a local boat-builder in South Shields. He was not really an inventor but after seeing the tragedy of the Adventure his thoughts had already turned to how to design a boat for this specialized need, and he had been doing research on the subject. He might have been among those who encouraged the local business community to sponsor a local rescue station, but he declined to be member of the committee that would create the specifications and choose the winning design so that he could retain eligibility to design and build it.

The wreck of the Adventure was only the latest of many such tragedies and various attempts had been made to design a specialized craft for the purpose. Parliament was even offering a very large challenge prize of £1200 for a lifeboat suitable for rescues in extremely stormy conditions but no one had yet successfully claimed it.

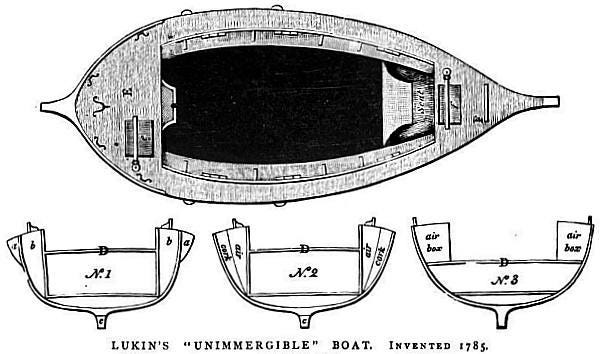

Henry Greathead entered the local competition, submitting a scale model of his design. His proposal was an upsized traditional Norwegian clinker-built yawl-style whaling boat; 30 feet (9.1 metres) long and 10 feet (3 metres) wide, but with a heavily weighted curved iron keel to ensure that it would stay upright. It had a prow at both ends, and was steered using special long oars called sweeps instead of a rudder so it could be rowed equally well in both directions. His design borrowed freely from a lifeboat that had been developed five years earlier by a respected London coach-builder and inventor, Lionel Lukin, but it was quite different from his design.

Lukin was a wealthy gentleman inventor, motivated by a desire to contribute towards the solution for a clear need rather than by the money. He had patented his design but had released his patent into what we now call the public domain. He had a small prototype of his design built that was tested on the Thames, and then had the boatyard build a new full-size one with modifications which was being used in the open waters of the English channel. But Lukin’s design had not yet been tested in stormy conditions.

Lukin had not submitted his own design to the South Shields businessmen; he probably didn’t even know about their call for a lifeboat design or their small prize. The committee received two proposals that they believed had merit. The other was from the local parish clerk and amateur inventor William Wouldhave (a rather unpleasant person, by all accounts) with no nautical experience. Structurally his proposal was for a flat-bottomed boat similar to the local fishers’ cobles, but which was to be made of copper and have cork flotation panels affixed to it so that it could not sink.

The jury decided to declare a tie and split the prize money between the two of them, and they commissioned Greathead’s shipyard to build a boat nominally designed by one of their members named Nicholas Fairles which included what the committee considered to be the best features from both entries (although in truth it was mainly Greathead’s proposed design.) It certainly did not include what the whole committee thought was the ridiculous idea of making a boat out of metal.

The inventor Wouldhave took offence and considered his half-share of the prize money to be an insult and turned it down. He was especially aggrieved because he believed that his boat, if built and tested, could be righted as was called for in the contest’s call for proposals. Henry Greathead made no such claim about meeting that specification. His boat was designed not to capsize in the first place. On the other hand, he recognized the benefits having cork panels for buoyancy and gladly took his one guinea prize as well as the commission to build what was basically his boat with internal and external cork added to it.

I could find nothing in my research one way or the other as to whether Greathead and Fairles collaborated on any design changes while the boat-building progressed. After that boat, I don’t know who named it Original, proved its worth over the next few years in the very harsh North Sea conditions Parliament awarded Greathead the £1200 prize for his invention. As far as I know, no Lukin boat was ever actually deployed a working lifeboat before that time. There is some controversy (especially from folks who think Lukin should get the credit) but it is Greathead who is generally considered to have been the inventor of the world’s first purpose-built lifeboat. Lutkin and Wouldhead both have brief Wikipedia entries that cite the basis for their claims to credit for that accomplishment, but Nicholas Fairles doesn’t even have that.

Greathead’s shipyard built 31 such boats. He could have built more, especially after receiving Parliament’s prize, but like Lukin he chose not to maintain exclusive rights to his design. A purpose-built lifeboat was an idea whose time had come and he knew that his own design expanded upon ideas from others. Instead, he willingly shared his plans with other boat-builders, encouraged them to make improvements on his design, and upgraded his own boats with improvements that others developed (such as self-bailing capability ca. 1820.) Whether built by him or others, lifeboats based on his design came to be known as “Greathead’s lifeboats.”

The lifeboat Zetland

Zetland was the eleventh of the 31 lifeboats that Greathead’s shipyard built. It was commissioned in 1800 by the residents of the small fishing hamlet Redcar, about 30 miles down the coast from South Shields. The town is on an east-west stretch of beach facing north.

Redcar’s origin as a fishing village date back to the 14th century, located on lowland coastal sand dunes amidst the marshes just south of the mouth of the River Tees in North Yorkshire. The town’s name has nothing to do with a colourful automobile: It is believed to derive from the Old Norse kjarr, meaning marsh, combined with either the Old English word for reed (hrēod) or red (rēad.) The biggest risks for ships there are being driven by a storm onto a partially submerged rocky ledges just off the town, or onto the area’s many sandbars, and then repeatedly being exposed to the battering rams that are the North Sea’s waves.

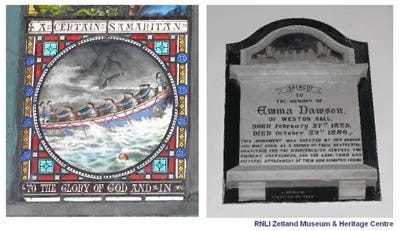

The lifeboat itself cost £200, and at least an equivalent further amount was needed have a carriage made for it, building a boathouse, and acquiring ropes and other lifesaving gear. The start-up costs included a generous contribution from the local lord and lady, Christopher Holdsworth Dawson and his wife Emma (née Carter) even though their manor home Weston Hall in Otley was over 60 miles inland.

The lifeboat arrived on October 7, 1802. Manning it with its relief crews would require participation from a significant proportion of the entire able-bodied male population of that small fishing village. Getting it from its boathouse and into the water would often require help from many others, women as well as men.

The evening that the boat arrived was an occasion for a community celebration. According to a contemporary account: “In the evening the fishermen were regaled with ale to drink success to the boat and the health of the builder.” They also declared “in the most voluntary and heartfelt manner” that the lifeboat would never want for hands to man her.

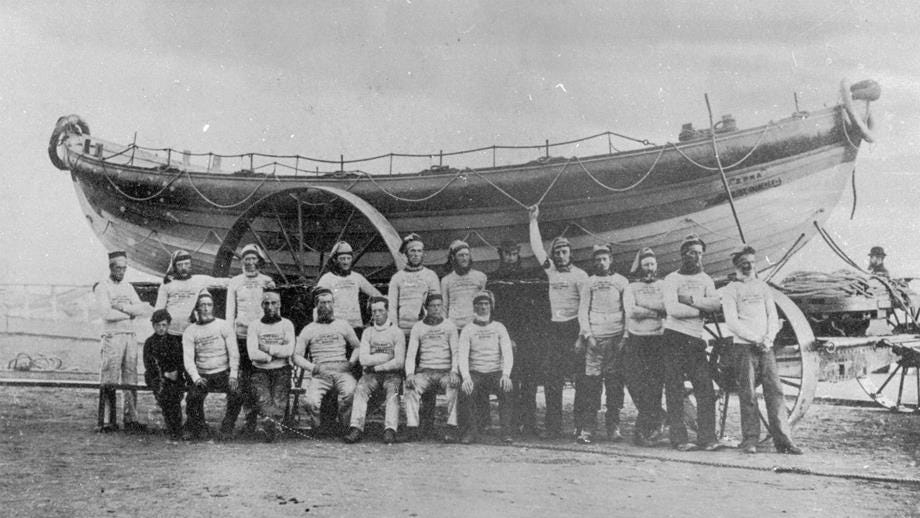

The townspeople immediately began to train and have practices with the lifeboat before the winter storms set in. All of the fishermen of course were expert rowers, and they had the callouses to prove it, but crewing a Greatshead lifeboat required new skills. They were used to rowing two oars at a time, with perhaps one other person rowing with them. On the lifeboat there would be ten or more rowers with one, and under particularly harsh conditions, two men on each oar, all working under the direction of a coxswain. The coxswain and bowman had to learn how to steer the craft with its unfamiliar sweep oars. Lives, including their own, depended upon learning how to do all this not just during the day and in good weather, but also at night and in harsh stormy conditions.

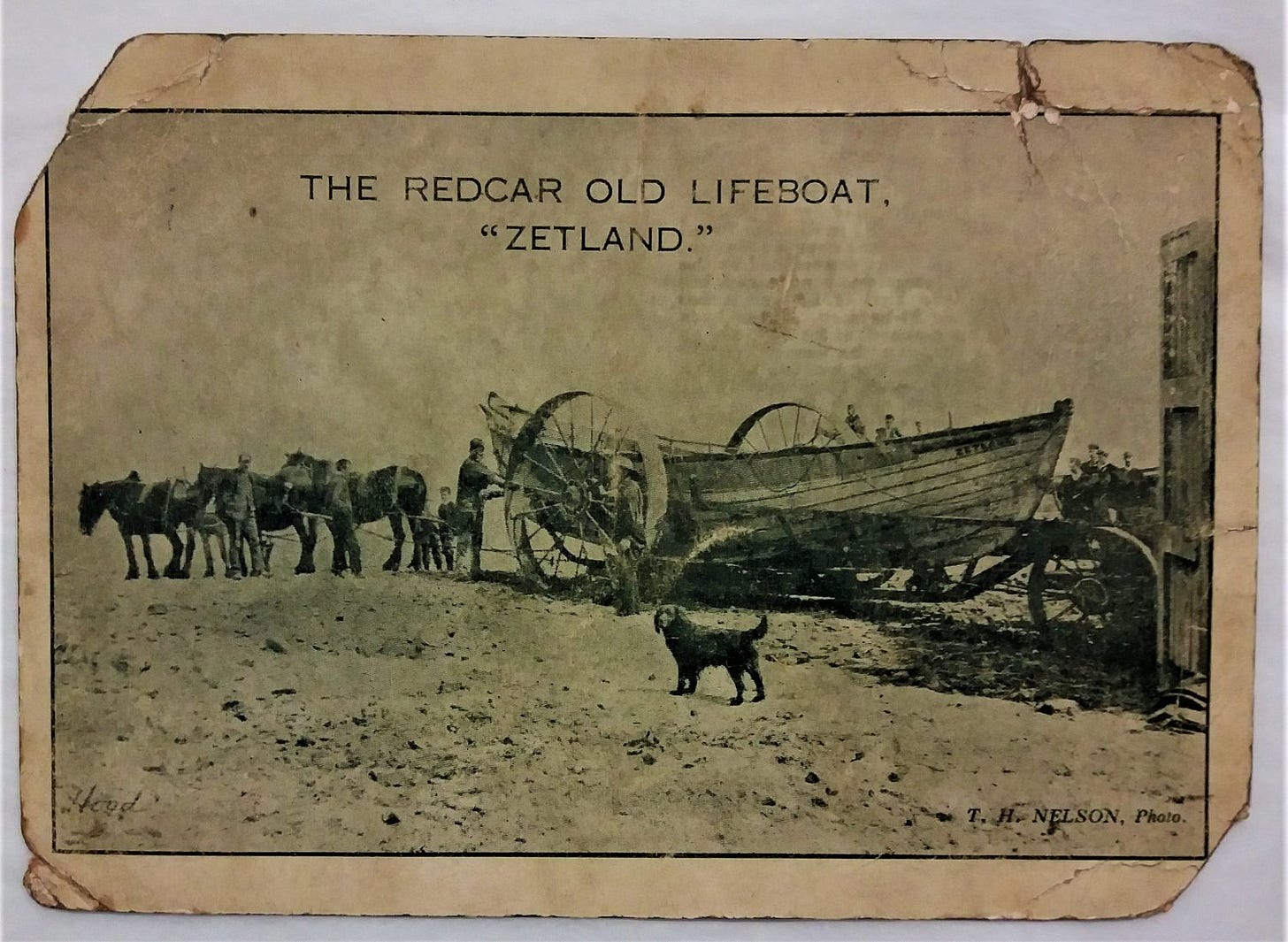

They also had to practice moving the boat over the sands on its carriage. Rowing a lifeboat in a howling gale is exhausting and dangerous work, so the lifeboat was intended to be wheeled overland on its carriage and launched from as close to the shipwreck as possible. Generally, a team of horses could be used, as shown in the above photo, but the image in the puzzle in which both men and women are pushing and pulling the boat is also accurate.

Redcar had no protected harbour. Just offshore from the village is an outcropping of rocks that presents a significant hazard for maritime navigation but also offers a bit of protection from the waves for sandy Redcar Beach. Since time immemorial the local fishers had learned how avoid that hazard whatever the weather and under various tidal and current conditions.

But when the Redcar Rocks (AKA Coatham Rocks or the Salt Scars) claimed a passing vessel, time was of the essence if lives were to be saved and it takes quite a bit of time to hitch up a team of horses. When a ship was on their rocks the lifeboat was often launched directly from Redcar Beach, and as is shown in the puzzle’s image, almost all of the available able-bodied townspeople were involved in pulling and pushing it down into the water by hand.

And those learning curves are without even getting into the live-saving skills themselves. There was a lot to learn and it was not long before both the lifeboat itself and its crew’s new-found training and skills were put to the test. Here is an account from a 2002 issue of the RNLI’s Lifeboat magazine (lightly edited):

“It was only a few weeks to wait before she was needed. No one knows who first raised the alarm. The name or names have long been forgotten. Who would have been out on the lonely sands of the Tees estuary in such dreadful weather? Perhaps a Customs and Excise man on patrol. Whoever it was, they brought the news to Redcar about noon that a ship was ashore on a sandbank on the north side of the Tees.

In the little village of about 100 houses built on the sand dunes, every inhabitant was soon astir. All were eager to launch the new lifeboat, which had arrived just two months earlier. A gale was blowing from the northeast and a high sea was running. To launch at Redcar and row more than 4 miles to the wreck was out of the question. The men who would form the crew would soon have been exhausted in such conditions.

Better by far to take the lifeboat on its primitive carriage along the sands and launch as close to the wreck as possible. Drag ropes were laid out and every able-bodied inhabitant seized them. So determined were they for a successful rescue that they had hauled the lifeboat almost 3 miles before a team of horses had been hitched together and caught up with them to take over the heavy work.

When a place nearest the wreck was reached the lifeboat was turned to face the sea. The crew jumped on board and the remainder of the eager party pushed her into the water. Knee deep, then waist deep, they struggled in icy cold, foaming waves until she was afloat. Ten oar blades dipped in unison and powerful arms soon had the bow knifing forwards.

Breaker after breaker was surmounted until they reached the wreck, which was found to be the brig Friendship of North Shields. Her crew of nine were close to exhaustion from the cold and their ordeal. They were taken on board the lifeboat and brought to the shore. It was not a moment too soon for shortly afterwards the Friendship was broken up by the force of the sea.

There was barely time for rejoicing at the rescue before another brig was driven ashore - the Sarah of Sunderland. Again the crew jumped into the lifeboat and again the battle with the breakers began. In a short time six more merchant sailors were brought to safety.

Tired and jubilant, the people of Redcar took their new lifeboat home along the gale-swept sands. She had accomplished all that had been asked of her and more. Little wonder that the townsfolk were soon proclaiming that she was worth her weight in gold.

Those were just the first of the Redcar lifeboat’s many rescues. In August 1829 the still-unnamed lifeboat had one of its most impressive rescues. An unseasonable fierce nor’easter gale had wrecked a ship onto the same rocky outcrop north of the entrance to the River Tees as the Redcar lifeboat’s first rescue. By then a new lifeboat station had been established closer to there in Seaton Carew, but the prospects for their relatively-inexperienced crew to have a successful rescue did not look promising given the particularly harsh weather. They telegraphed the experienced Redcar station with its larger lifeboat for backup.

Their worries were well founded. The extremely rough sea and bitter driving wind was indeed too much for them to handle, and after three hours of braving the heavy gale and tremendous seas the exhausted crew were forced to return to shore. In the meantime Redcar’s lifeboat had been towed the four miles to the river by horses, accompanied by all of its crew members and their reserves.

They launched with two men on each oar, two additional steersmen, and two men to bail water. (In 1823 the boat had been retrofitted by Greathead with newly-invented relieving tubes and valves to make her “self-bailing” but the waves were washing over the boat so much that the relieving tubes would not be able to keep up. Those same waves were so violent that the rowers had to be lashed to their seats so as not to be thrown overboard.

But the rescue was successful and they were able to retrieve the captain, his wife, and the eight crew members from the ship shortly before it was demolished by the pounding waves. Coastguard Lieutenant RE Pym, the boat’s volunteer coxswain, was awarded the RNLI’s highest honour, its rare Gold Medal for gallantry. (That seems to have been part of a pattern in granting the RNLI’s medal awards: They only gave credit to the coxswain for a lifeboats’ accomplishments, not to the whole team who had faced and overcome danger together.)

For many years the lifeboat had no name. I suspect that locals just called her “the lifeboat.” In fact, it was much later in 1838 when she was named when, in association with the coronation of Queen Victoria, Lord Dawson’s father was bestowed the title Earl of Zetland. (“Zetland” is an archaic name for the Shetland Islands, about halfway between Scotland and Norway.) The Dawson family had continued to be strong patrons of the Redcar lifeboat station and so the boat was gratefully named in their honour.

Another rescue that competes with that feat for being Zetland’s greatest achievement was on November 15, 1854 when the brig Jane Erskine ran aground on the Salt Scar rocks just off Redcar. Here is local historian Kerry Shaw’s account of that event (lightly edited) based on a 1894 reminiscence written by 76 year-old Willie Dobson:

It was the 15th November and a strong south-easterly wind had been battering the sea off Redcar all through the night. In the early hours of the morning, the brig Jane Erskine had been driven onto the Lye Dam Scar rocks to the East of Redcar. …

[30 year-old] Willie Dobson, being up before daybreak as most fisherman are, hears about the ship and runs to let his father know. Soon they are launching their coble (small fishing boat) to join other local fisherman who are already braving the rough sea to get to the stranded ship. At this point there is no need for the lifeboat to be called and it is actually a great sight for local people. It means an opportunity to make money to put some food on the table for their families (or maybe for some – a few pints at the local).

If a ship is stranded on the rocks (and not actually wrecked) it is possible to re-float it, with the help of skilled men and equipment. The fisherman get to the ship and come to an agreement with the Captain as to what money will be exchanged in return for them [helping to get] the ship off the rocks. Once terms are agreed, the fishermen lay an anchor in deeper waters and take a cable to the stranded ship. They will wait for the tide to rise so they can drag the ship off the rocks using a windlass (a large winch).

The storm was getting heavier as 26 of the local fisherman climb aboard the Jane Erskine ready to start the heavy work of turning the windlass. Willie Dobson, Jim Thompson and Charlie Cole were waiting in a coble nearby as the sea becomes steadily rougher and were told to go ashore to wait until the tide flowed. Just as Dobson was taking a gulp of his mug of tea at home, a friend ran in and told them that the ship was showing a distress flag. They all ran back to the shore to see the Jane Erskine lying on its side and the men on board, in great danger, are clinging to any exposed part of the ship they can find.

The muster call was immediately put out for the Zetland lifeboat by the drummer boy beating his drum loudly to the tune of ‘Come along Brave Boys’ to alert the lifeboat crew that there is trouble. The wind picked up strength and the waves grew heavier as the Zetland and her crew launch into the sea. The regular Coxwain, Robert Shieldon was not present on this occasion so George Robinson volunteered in his place and ordered the boat to be driven windward which will favour the lifeboat’s course.

By now, the Jane Erskine is being pumelled by the onslaught of the wind and waves and the Zetland managed to get alongside and hold steady long enough for the 26 fishermen, and the Erskine’s captain and crew of nine men to jump aboard. Within seconds, the ship broke up completely.

The Zetland lifeboat, still battling the storm, made her journey back to shore with 52 people on-board altogether! That is the largest number of people that she ever carried.

The RNLI and self-righting lifeboats

Now, let’s step back in time for a bit to the founding of the Royal National Lifeboat Institute. Throughout the late-1700s and early 19th century many lifeboat stations were established by communities around Britain but the coverage was spotty. Despite the favourable national attention that a successful rescue could bring to a town not every coastal community had the resources or inclination to establish a service whose primary role would be endangering their own lives to rescue sailors that they didn’t know. And, as you might guess, some of the local lifeboat organizations that were established proved not to be well-managed, or their crews were not well-trained, and many such stations proved to be short-lived.

In 1823 Sir William Hillary began lobbying in London for the creation of a national maritime voluntary service to deal with shipwrecks. He had some credibility in this field, having been the founder, patron and coxswain of a lifeboat station in Douglas on the Isle of Man. His initial lobbying had a broad objective, dealing with the protection of property through provision and enforcement of lawful salvaging, as well as saving lives. His proposals fell on deaf ears at the Admiralty.

The following year he narrowed the purpose of his proposed service just to saving lives, not property, and he changed the target of his lobbying to aristocrats and wealthy philanthropists instead of the Admiralty. This time his proposal quickly became a national movement, especially after King George IV agreed both to be a patron and to allow the name of the society to bear the word “Royal.” The honourary leadership positions of the new organization were held by an Earl (who was also Britain’s Prime Minister), a Duke who was also Chairman of the East India Company, and the Archbishop of Canterbury, but the actual management board was headed by Sir William and the East India Company merchant and ship-owner (as well as amateur lifeboat designer) George Palmer.

Thus, the RNLI was born and donations poured in. (Actually, its name was much longer back then – The Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck – but I’ll just keep calling it the RNLI to avoid confusion.) Much of it was money that otherwise would have gone directly to community-based lifeboat stations, but the wealthy philanthropists presumably appreciated that a national organization would be in a better position to assess whether proposals were viable, and the new organization promised to invest their money where the benefits would be greatest. They may also have appreciated that their donation to the RNLI gave them a reasonable excuse for no longer accepting applications directly from numerous community-based supplicants.

Initially the RNLI’s modus operandi was to be providing operational, capital and equipment acquisition grants to local lifeboat stations, and recognition as well as generous financial rewards for successful rescues as an incentive for local volunteerism. Before long it was also conducting research into improved lifesaving gear, and establishing and operating lifeboat stations under the RNLI name.

After the initial enthusiasm the donations from wealthy philanthropists waned considerably as other charitable causes were made more fashionable by the likes of Charles Dickens and the rise of the abolitionist movement. But the RNLI had a substantial endowment from that initial push. The London bureaucracy of professional staff grew and they moved towards operating their own lifeboat stations under a mixed professional/volunteer business model: Their coxswains were salaried RNLI employees, and RNLI lifeboatmen were paid honorariums for participating in practice sessions as well as for successful rescues.

As mentioned above, Redcar lifeboat station was one of many that had been founded and self-financed by local coastal communities before the founding of the RNLI. By 1839 the RNLI was supporting over 30 lifeboat stations around Britain. To facilitate handling of grants for the independent local stations the RNLI encouraged them to merge into regional associations that would become the conduit for its communication and grants.

Sometime before 1843 the various lifeboat stations near the mouth of the River Tees with its port city of Middlesbrough, organizationally merged as the Tees Bay Lifeboat and Shipwreck Society. That organization handled all financial matters and equipment procurement – all of the paperwork functions - and in keeping with RNLI standards it became the official owner of all of the local boats, boathouses, and equipment.

But over the coming decades as the RNLI’s donation base dwindles the organization was clearly giving priority to maintaining and expanding its own lifeboat stations rather than providing grants to the independent community-owned ones. By 1848 the RNLI’s growth proved to be too much for its endowment fund to sustain.

Frankly, the problems were years of poor management, over-spending, an inefficient business model, a complete absence of creativity in their public relations and fund-raising, and increasingly poor relations with the member local lifeboat stations. (For more about that, see this academic paper.) The RNLI was still living off the proceeds from their first year of fund-raising from wealthy philanthropists when they had raised nearly £10,000 but as philanthropic fashion had moved on their annual revenue from donations had dropped to about £440.

A review by the Admiralty found that of the RNLI’s 100 lifeboats only about 55 were considered to be well-maintained, and the majority of those (probably including the Zetland) were considered to be obsolete by the organization’s own standards. Basically, the organization was overdue for a change in leadership and the death of its founder Sir William Hillary in 1847 provided the opportunity for that to happen. With encouragement from one of the other founding leaders who had been overshadowed by Sir William, Lord Algernon Percy, the Duke of Northumberland, became the RNLI’s first new president since its founding.

The Duke’s first priorities were to shake-up the organization and to reawaken public interest in the importance of its role of rescuing shipwrecked sailors and passengers. An opportunity to show that the organization was changing came with the upcoming Great Exposition Works of Industry of All Nations that was going to be held in 1851 in the Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park under Prince Albert’s patronage.

The Duke personally offered a £100 challenge prize for the best proposed design of a self-righting lifeboat (in the form of a model), and a further £100 to build a prototype to test its suitability for purpose. Other parameters for the contest were that the successful entry had to be self-bailing, lightweight enough to be portable on land, and inexpensive to build. The models of the top contenders would be exhibited in the Crystal Palace and the winning design would be announced there.

At the time, being self-righting had long been the holy grail for lifeboat design. Many designers all over the world had come to understand the physics of how that could be possible but all of the previous engineering solutions had drawbacks (such as being too heavy) that made them impractical.

As had been hoped, the competition drew both considerable public attention to the role of the RNLI (and annual donations got a 150% surge over their previous year’s level) as well as contest applicants from all over the world – 280 of them! £100 was a lot of money in those days, but perhaps more importantly, whoever first invented a practical self-righting lifeboat would literally get credit for making history. The winner of the Northumberland Prize was James Beeching, a Great Yarmouth boat-builder whose previous claim to boat-design excellence had been for building the best boats for smuggling.

The prototype lifeboat proved satisfactory and several were built to Beeching’s design before James Peake, a master shipwright who was also an RNLI vice-president, developed an improved model that included improvements based on features of other boats in the competition as well as a few of his own ideas that came from feedback from the early trials of Beeching lifeboats. In 1852 his Peake-class lifeboat was considerably lighter in weight than the Beeching, and drew only 14 inches (36cm) of water. It was made the RNLI’s standard base for lifeboat design, and was soon accepted internationally as the world standard.

Meanwhile, Lord Percy was continuing with his reforms of the national organization, and shifting its fundraising model from being focused exclusively towards wealthy philanthropists to including street campaigning to solicit donations from everyday people. The reforms were underlined by a rebranding change of the Institution’s name from the clunky Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck to the Royal National Lifeboat Institution.

Back to the Redcar and the Zetland

Throughout the 1830s and ‘40s many local lifeboat stations in Britain or their regional organizations had become financially stressed and needed to join the RNLI in order to continue to receive any significant operational and capital funding from that organization. I suspect that Redcar had adequate financial support because of their continuing direct patronage from the Dawson family and the North Yorkshire chapters of a fraternal organization (modeled after the Freemasons) called the United Order of the Free Gardeners. But that was not the case for all of their neighboring stations. In 1858 the whole of the Tees Bay Lifeboat and Shipwreck Society was voluntarily absorbed into the newly-reformed RNLI, and all of its assets, including the Zetland, became owned by the revived national organization.

Under the RNLI, individual lifeboat stations continued to be manned by volunteers but they were under the direction of a coxswain who was an RNLI salaried employee. Besides being the leader afloat, coxswains were in charge of training and operational readiness. Twice-a-year the RNLI would send in an inspector (almost invariably a former Naval officer) to audit the books and assess the station’s compliance with RNLI standards. Otherwise, the lifeboat stations operated much like local service clubs, volunteer fire departments, or sports teams.

During the off-season their parallel to being like sports teams would be particularly apt because the various member communities sponsored races and rescue skills competitions with their neighbours during that time of year. I suspect they were among the coastal towns’ biggest sporting and social events of the year. Besides being fun, these events developed camaraderie between the crews from different stations. That was valuable because, as we have already seen, circumstances sometimes required the crews to come to each other’s aid.

In February 1864, six years after becoming part of the RNLI, Zetland was badly damaged during the rescue of six sailors from the brig Brothers. The coxswain informed RNLI headquarters in London and applied for funding to have it repaired ASAP since the storm season was still in full swing. The RNLI sent a ship’s carpenter to examine the boat, who determined that it was no longer seaworthy. He reported that to London, who were quite used even to new lifeboats becoming unseaworthy. He was told to follow the organization’s standard practice of demolishing it on the beach and salvage what re-usable bits he could from the boat.

The local residents became – well, let’s just say they were very, very angry and prevented the carpenter from commencing his demolition of their belovéd Zetland. From their point of view, Zetland was still their boat. It was their grandparents who had raised the money to have her made, and they were more willing to risk their lives in her than in one of the RNLI’s new self-righting lifeboats.

That last part needs a bit of explaining. Ever since the Beeching and later the Beeching-Peake self-righting lifeboats had gone into service the statistics were accumulating, and word was spreading in coastal communities that there were more deaths among the rescue crews in them than from the older non-self-righting ones.

The criteria for the Northumberland Prize contest had not been to identify the best lifeboat design – it had been to identify the best self-righting lifeboat. No one had questioned whether self-righting would be in improvement over not capsizing in the first place. The engineering methods (at that time) for making a boat self-righting involved not just a heavy keel but also having air pockets at the ends of the boats that were elevated above the vessels’ centre-of-gravity midline, as well as that the boat be long and narrow.

Those features made self-righting boats unstable, so they would more easily capsize than a broad-beam lifeboat like a Greathead’s. The high domed tops of the air compartments at the ends of the boats (see the above model and engraving) also made it more difficult for shipwrecked sailors to climb into the lifeboat. The “self-righters” had their proponents, but many lifeboatmen were suspicious of them and called self-righting boats “self-capsizing” or “roly-poly” boats. (Note: See here (p.256), here, and here for discussion of the physics of self-righting, and about how the debate about whether the merits of that feature outweigh their disadvantages continues to recent times.)

Negotiations ensued. Eventually the RNLI agreed to let the community have Zetland back on the condition that they not be responsible for it, and that if it were to be fixed it would never be used in competition with the RNLI’s replacement boat for the community. I suspect that they assumed that the Zetland would just get dragged up higher on the beach above high-tide and left to rot like so many other no-longer-serviceable boats.

The RNLI had not factored in the extent to which the venerable 62 year old Zetland was loved in the community, or the willingness of the Dawson family (especially Emma) to support the people of Redcar (which was no longer a small fishing village but with the building of a railway spur line from Middlesbrough had evolved into a Victorian-era seaside holiday community.) In 1869 Lord Dawson died and his wife Emma became the head of the household. She donated enough money to repair Zetland and to provide it with a boathouse and gear to be a back-up for the replacement RNLI lifeboat Burton-on-Trent.

The lifeboat men of Redcar never did warm up to the (very heavy and hard to move over the sand) Burton-on-Trent roly-poly, and most of the people in the town were getting pretty fed up with what they saw as the continuing high-handedness of the RNLI run by a bunch of toffs in London. (Even today, one quarter of all British lifeboat stations are independent of the RNLI, run by local charitable organizations.)

The people of Redcar had agreed that if the Zetland was returned to them it would never be used in competition with the Burton-on-Trent, but they had not promised never to have their own independent lifeboat station. In 1875 Emma Dawson and the North Yorkshire chapters of the fraternal organization United Order of Free Gardeners agreed to establish an independent lifeboat station in Redcar, complete with a newly-built non-capsizing lifeboat. The lifeboat was officially christened Free Gardener but it came to be universally known to the locals as Emma. At the same time they donated £700 to build an impressive brick boathouse which included meeting rooms for the crew, and accommodation for Thomas Hood Picknett who for many years had been coxswain of the Zetland and was the new cox for Emma. Legally, both the lifeboat and the station were owned by their primary patron, in this case, Emma Dawson.

In the meantime, Zetland continued to be available as backup for both Emma and the RNLI’s Burton-on-Trent. It was maintained in ready-to-serve condition, and I presume was crewed by lifeboatmen who were past their prime but still capable of serving if needed. They practiced together but were not needed very frequently until on October 29,1880 the crew of Zetland performed its last rescue.

The day before a particularly severe North Sea gale had begun causing shipwrecks all up and down the Yorkshire coast. The lifeboat Emma rescued 12 sailors from two different ships but returned from the second rescue with a large hole in her hull. Burton-on-Trent was engaged in another rescue when at about 11:00pm the brig Luna crashed into the recently-built Redcar Pier after having lost her anchor at sea.

The collision with the iron pier caused both masts to break and be blown down and the Luna cracked in two. The captain’s leg was broken when an iron column crashed through the cabin skylight. The deck and surrounding sea were covered with debris that was being whipped around by the fierce gale winds. It was 4:00 am before the Zetland could safely get near to the boat and rescue the captain and its six sailors.

Stories about the damage and loss of life caused by the storm filled the national newspapers in the coming days, but the successful rescue by the 78 year old Zetland provided a notable “good news” story within the national hardship and tragedies. Although Zetland was not an RNLI lifeboat the organization awarded its crew a special £100 stipend for their valour. I could not find information as to whether the Zetland was officially retired from service right after that event, or whether it nominally remained in service for a while longer. But it was never again used for a rescue.

In all my research I found one, and only one, source that indicated why Emma Dawson had such a close affinity for the town of Redcar. It said that she spent time there both before and after seaside holidays became fashionable in the mid-19th century. Apparently she liked that the local people there treated her just as if she were a friend and were not intimidated by her high-born social status. According to this article she had a similar warm relationship with the inhabitants of a village in Germany where the Dawsons had a hunting lodge.

Emma Dawson died just three years after Zetland’s last rescue. Her 25 year-old grandson and heir, William Christopher Dawson, was not at all keen on financially supporting a lifeboat station in Redcar. In 1884 he offered to donate both the new lifeboat Emma and its fine brick station to the RNLI, but they turned down his offer. I don’t know why. That was despite the fact that they themselves were becoming less infatuated with self-righting lifeboats and had begun to again provide stable non-capsizing ones to some lifeboat stations.

According to local historian Kerry Shaw’s blog:

The Emma lifeboat ended up saving upwards of 64 lives, but exact records of this, and of her eventual fate, are still a mystery. She made her last rescue on 18th October 1898, when the Finnish barque (a sailing ship with three or four masts) Birger was caught in gale force winds and struck Saltscar. Only two members of her crew of fifteen survived. After that tragic day nothing is known of what became of the Emma. Some say she is at the bottom of the North Sea, others say she ended up in Hartlepool. Nobody knows for sure.

In 1907 the site of the Zetland’s boathouse in East Redcar, which had evolved into a local museum displaying it, was redeveloped and the museum was relocated to the brick lifeboat station near the centre of town that had been built for the Emma, and that it where it is still displayed today.

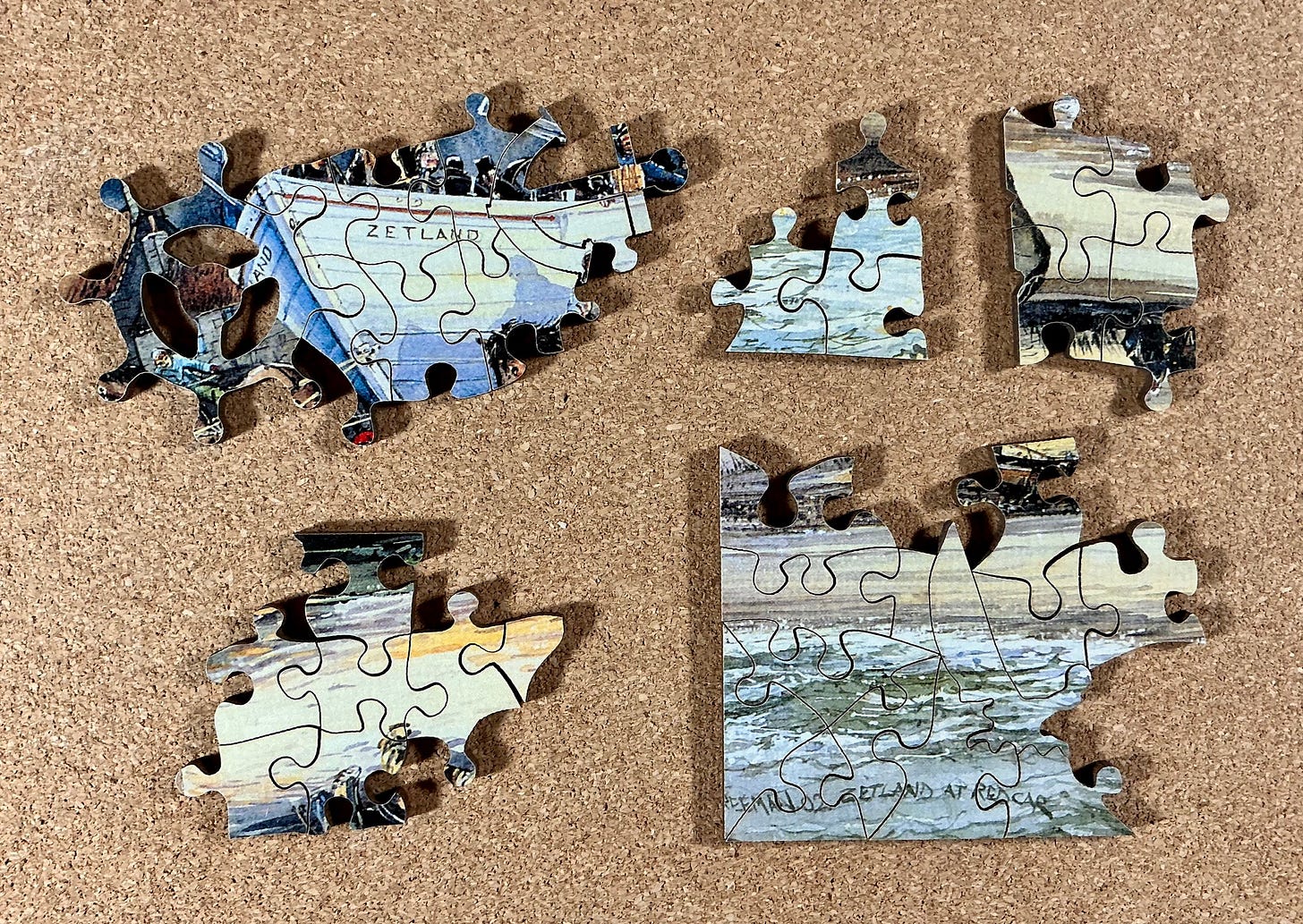

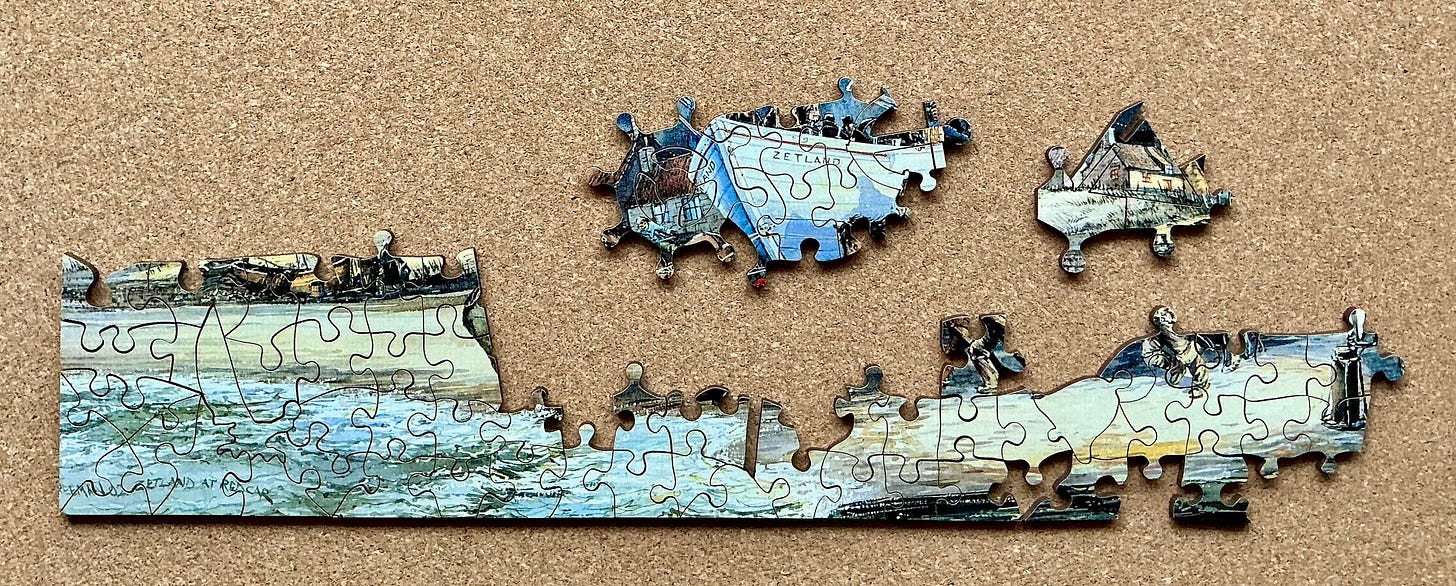

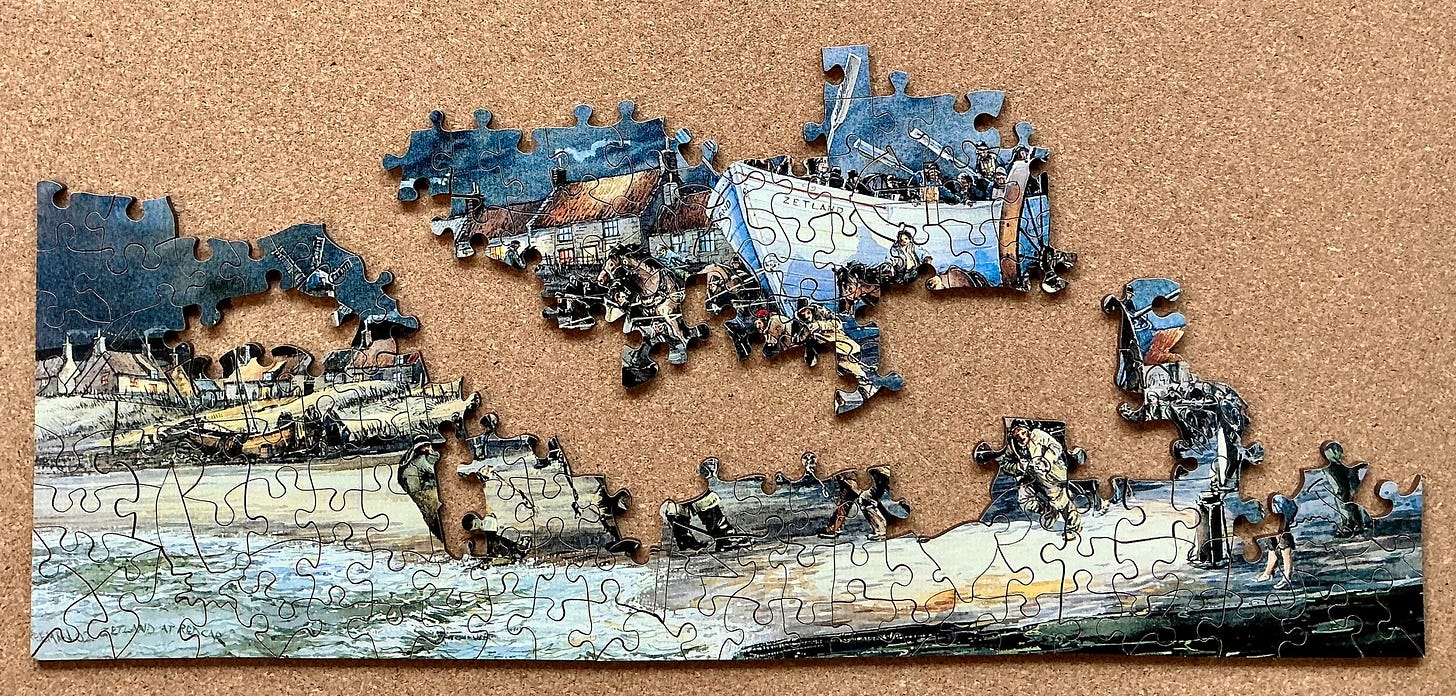

Puzzle assembly

It seems to me that describing my assembly experience would be pretty anticlimactic at this point. But this is a wooden puzzle newsletter/blog, not a lifeboat one, so here are my puzzle walkthrough pictures:

A song and final thoughts

Click here for a 4:00 illustrated YouTube video song about the Zetland lifeboat.

The Zetland served Redland and the North Sea sailors well. During its 62 years of active service as the town’s only lifeboat, and 78 years of service overall, multiple generations of crews saved over 500 people with only one of their own ever lost during a rescue. On Christmas Day, 1836, bow steersman William Guy was washed overboard and drowned during gale force winds in a vain attempt to save the crew of the Danish brig Caroline.

As Kerry Shaw eloquently puts it:

This boat was the vessel that saved over 500 lives! Not just a number. Each person had a mother and father, siblings, friends, children. Such an impact – just imagine someone you love being caught out there and their ship going under! These lifeboat men dropped everything to get to the lifeboat, haul it out in the most horrific conditions, putting their own lives aside to focus on saving a stranger caught out there. Just amazing.

Coming up:

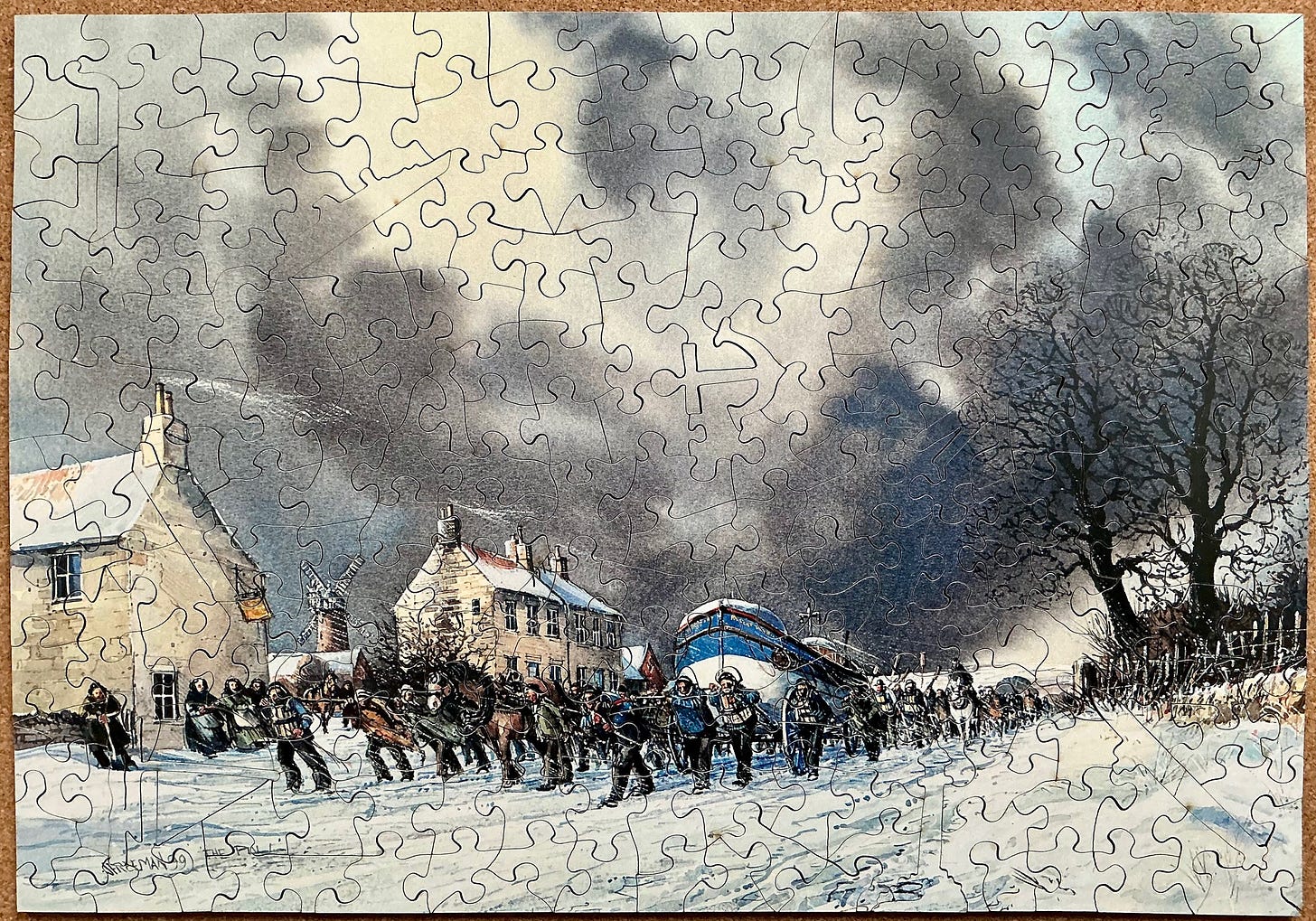

The image in last puzzle in this Wentworth binge subseries is another John Freeman painting depicting another actual 19th century heroic lifeboat rescue. I promise that write-up will be much shorter than this one.

Thank you, Bill, I can see how much work you put into this interesting posting. I know that we talked over the phone about how you were going to produce a series of essays that would key on what's in the pictures that have been used for some of these Wentworth puzzles. Well. you've outdone yourself. I'm learning more about rescue boats than I would even been previously able to question.

I hadn't realized how large these boats tended to be, nor how they have a rich history concerning their use from bases on land—not just uses as lifeboats stored on ships. What little I had known before was by word of mouth from British-born friends of mine who had lived in a coast-side house where rockets had earlier been stored to shoot out with long ropes to give sailors a chance to be hauled in from "man overboard" predicaments. My friends had told me about boats also housed nearby, but I hadn't known details about those boats until having access to your research. Your detailed account of the working career of one particular boat was fascinating!

My favourite photos in today's posting are the one of the model that won the Northumberland Prize and the one of the completed puzzle—just before the engraving and the preview of the puzzle you labelled "Coming up."

Regards,

Greg