46. Three Artifacts and two Ecru

Artifact Part 3 of 3. Five small (85-228 pieces) fine art puzzles made by Artifact; by five cutting designers with very different styles. (about 5000 words; 60 photos)

This is the third part in a 3-part series about Artifact Puzzles. If you want to start at the beginning go here. It was an essay about the history of the company and Maya Gupta, its founder. Part 2 was an in-depth review of the puzzles that they make. This part includes discussion, illustrated walk-throughs and puzzle-specific reviews of five of the puzzles that formed the basis for that review.

The puzzles are:

Rosso Angelo (Artifact) 228 pieces designed by Kathryn Flocken

Shiba Benten Pond (Ecru) 89 pcs Amy Tang

Armond Point Unicorn (Artifact) 101 pcs Jef Bombas

Fisherman’s Cottages (Ecru) 158 pcs David Figueiras

Van Gogh Landscapes Double-sided (Artifact) 150 pcs Tara Flannery

Spoiler alert

This posting shows the cutting designs and figural pieces of these five puzzles, which is information that Artifact does not include on its website; they want to preserve their designers’ ability to surprise you with their cutting tricks whimsies. If you have already decided to buy any of these puzzles I recommend that you consider skipping reading or looking at the pictures in that part of this essay.

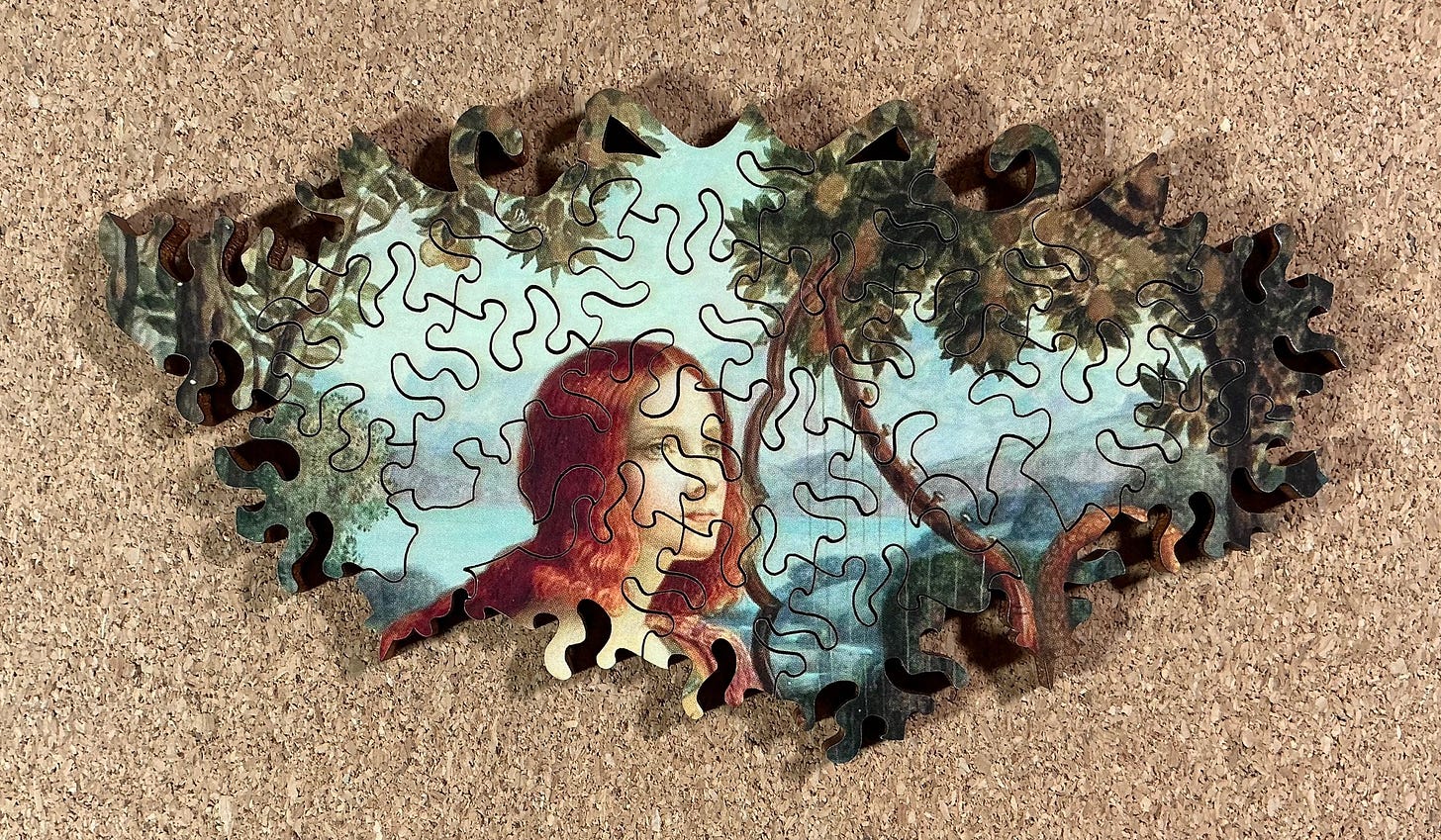

Rosso Angelo (Artifact)

cutting designer - Kathryn Flocken puzzle introduced in 2011

catalog listing Artifact rating – “average difficulty”

228 pieces decorative edge 22 x 27 cm ave. 2.4 cm²/pc 5mm 3ply

16 figural pieces mainly earlet connectors with a few wings and knobs

artist – Rosso Fiorentino painted in 1521

I’ll begin by discussing the painting even though (as always) I did my online research after assembling the puzzle. I had expected to find that this unnamed work, often called Cherub Playing the Lute, would be a detail from a larger work and indeed that is the case. It is a mannerist oil painting fragment from a lost altarpiece and is one of the relatively early works by Giovanni Battista di Jacopo (1495-1540) who went by the name Rosso Fiorentino (“the Florentine redhead”) or just Rosso. It is one of his most famous paintings. It seems odd that the nickname stuck because Rosso was a near-contemporary of a much more famous redhead who came from near Florence and had spent a substantial part of his career working in that city – Leonardo da Vinci.

The 39.5 x 47 cm oil painting on a wood panel is held by the Uffizi Gallery in the Medici’s Pitti Palace in Florence. According to their online catalogue, the dark background was added later, concealing that the little cherub had been at the base of a building. The full altarpiece would likely have been Rosso’s interpretation of a popular composition that was also painted by Raphael, Fra’ Bartolomeo, and later, Francesco Vanni.

The puzzle was designed in 2011 by Kathryn Flocken, a trained artist who spent many years as a professional silhouette-cutter at Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida. I get the impression from this interview in the Artifact Blog that this puzzle was from early in her career as one of the Artifact designers. Since she is a silhouette expert she sometimes assists other designers with their whimsies.

At 228 pieces this was the largest puzzle that I assembled in this Artifact small-puzzle binge. It was my first puzzle after having taken a seven week break from most puzzling to focus on my midwinter music project. I had bought the puzzle over two years ago and had done a particularly good job of forgetting what the image would be, although it did begin to come back to me once I got going on it.

Assembly was fairly straightforward because its difficulty was ameliorated by having good colour-clues in the image; i.e., there were regions in the artwork in which the pieces that had colours not found elsewhere in the image. I had not remembered that when I started the puzzle, but it really helped that my usual approach to sorting and flipping is also accompanied by some colour sorting:

I began with the relatively few pieces that had white. They came in warm and cool shades:

My two sub-assemblies then fit together, with the forearm letting me know which direction was “up” for this assembly. I then began with the ones with red. Again there were two shades – orangish and deep red. Then into bluish-grey pieces that had striations. (On a humorous note, as a sign that seven weeks without puzzling had made my assembly skills rusty it was only about here that I realized that this puzzle does not have any straight-edge pieces so it must have an irregular edge. Usually that would be one of the first things to catch my attention while pouring the pieces from their box.)

Next were reddish-brown ones with curvy striations which turned out to be the cherub’s ginger hair, and very dark brown, which in turn led into yellow. This particular puzzle is particularly well-suited for beginning with the image’s focus of attention. Getting the face in place when the puzzle was less than half completed felt like a real treat.

There were a fair number of yellow pieces so the straight lines of the strings on the fretboard of the lute proved quite helpful.

There were quite a few yellow pieces. I also tidied up along the edges of the assembly.

Finishing the yellow there was nothing left but about 60 remaining all-black pieces:

As you can guess, at this point things slowed down quite a bit, but it was always comforting seeing the little angel in front of me.

It took a while, but I got there:

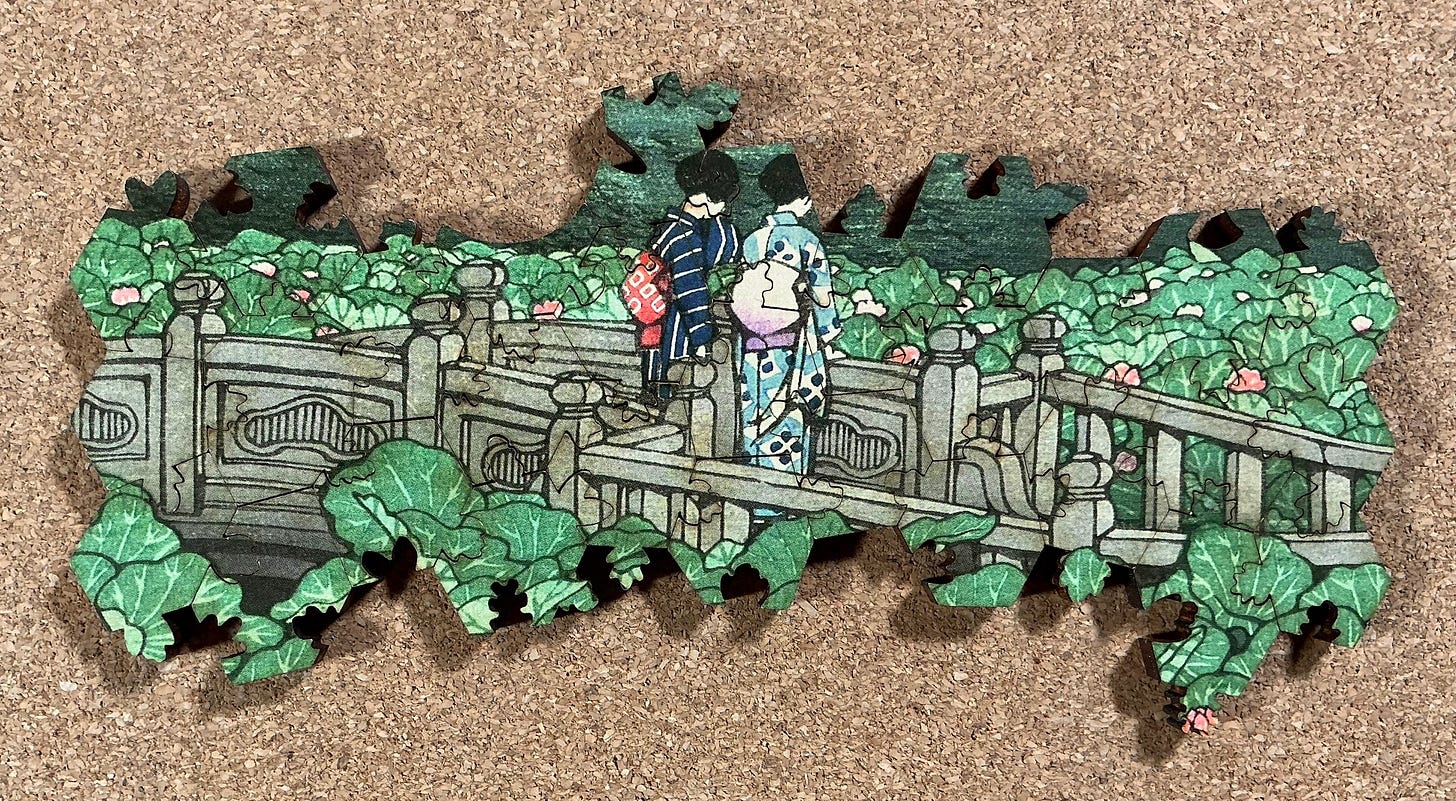

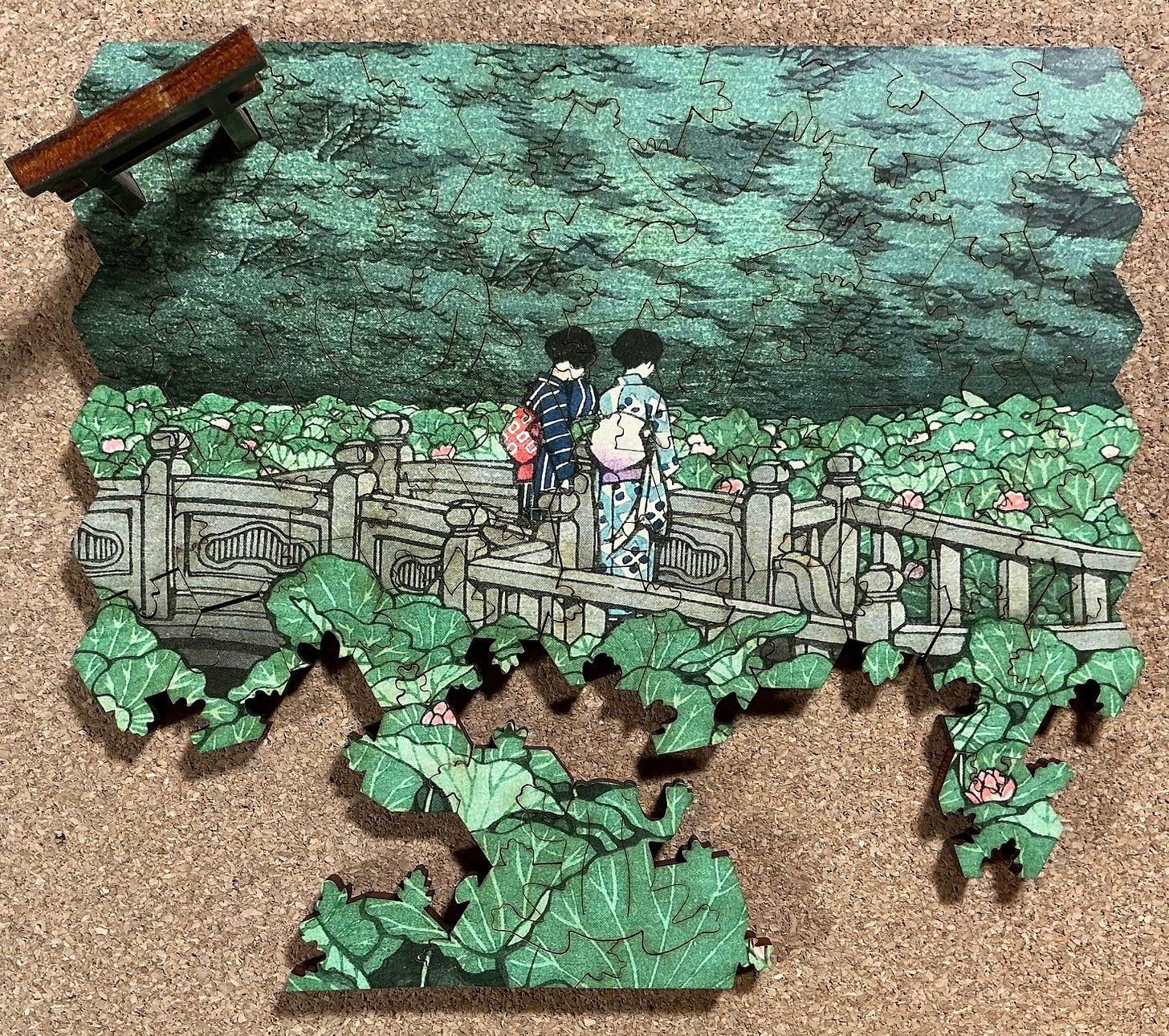

Shiba Benten Pond (Ecru)

Cutting designer - Amy Tang puzzle released in 2019

catalog listing “though small, offers a challenge” & “harder than average”

89 pieces semi-irregular edge 15 x 16 cm 2.7 cm²/pc 5mm 3ply

3 figurals 1 stand-up piece hexagonal pieces foliage connectors

artist – Kawase Hasui woodcut made in 1929

Actually, my seven week hiatus from assembly wasn’t as complete as I made it sound in the previous write-up. In late November my daughter Wendy and her family came out for a visit and we did four small puzzles together. This was one of them, but I forgot to take a photo or take notes at that time. So only about seven weeks later I did it again.

That is sure a lot of green, but it has different shades and textures, and only 89 pieces. As with the previous assembly, I again began by separating out the pieces that included some color other than green. I knew that they would build the image’s focus of attention – the bridge and people:

From then on it was just a matter of building up into the dark green forest foliage on the top . . .

. . . and the large lotus leaves and flowers down in front . . .

. . . until the puzzle was done:

The Artifact website describes this puzzle as “harder than average” for its 89 piece size. I would agree with that for the first time that I did it with Wendy, but I found this 2nd assembly that I did alone to be fairly easy. Not that I am complaining – that is what I was in a mood for at the time, and if I had found re-assembly while the image was still fresh in my brain to be difficult I would have been rather disappointed in myself despite that fact that there is some inherent difficulty in the cutting design with its many false edge pieces..

As you can see this puzzle has three very attractive figural pieces and one stand-up gate. The other pieces are mostly hexagonal, and the connectors are mostly various shapes of foliage. All in all, both its image and cutting work together to make a very attractive and fun mini-puzzle.

The puzzle designer in Amy Tang. The image is by Hasui Kawase (1883-1957) one of Japan’s foremost 20th century woodblock print designers. In 1956 he was awarded the prestigious honour of being named as a Japanese Living National Treasure. He has an international reputation for his “serene and poetic landscape prints that eloquently and masterfully depict dawn, dusk, snow, rain, nighttime, and moonlight”. His artistic impact goes beyond block printing: The famous Studio Ghibli animated filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki credits Hasui with having had a great influence on his work.

Hasui began as a painter but took up block printing in 1919, but unfortunately all of his early woodblocks and over 200 sketches were destroyed in the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923. If you want to learn more about him, here and here would be good places to start.

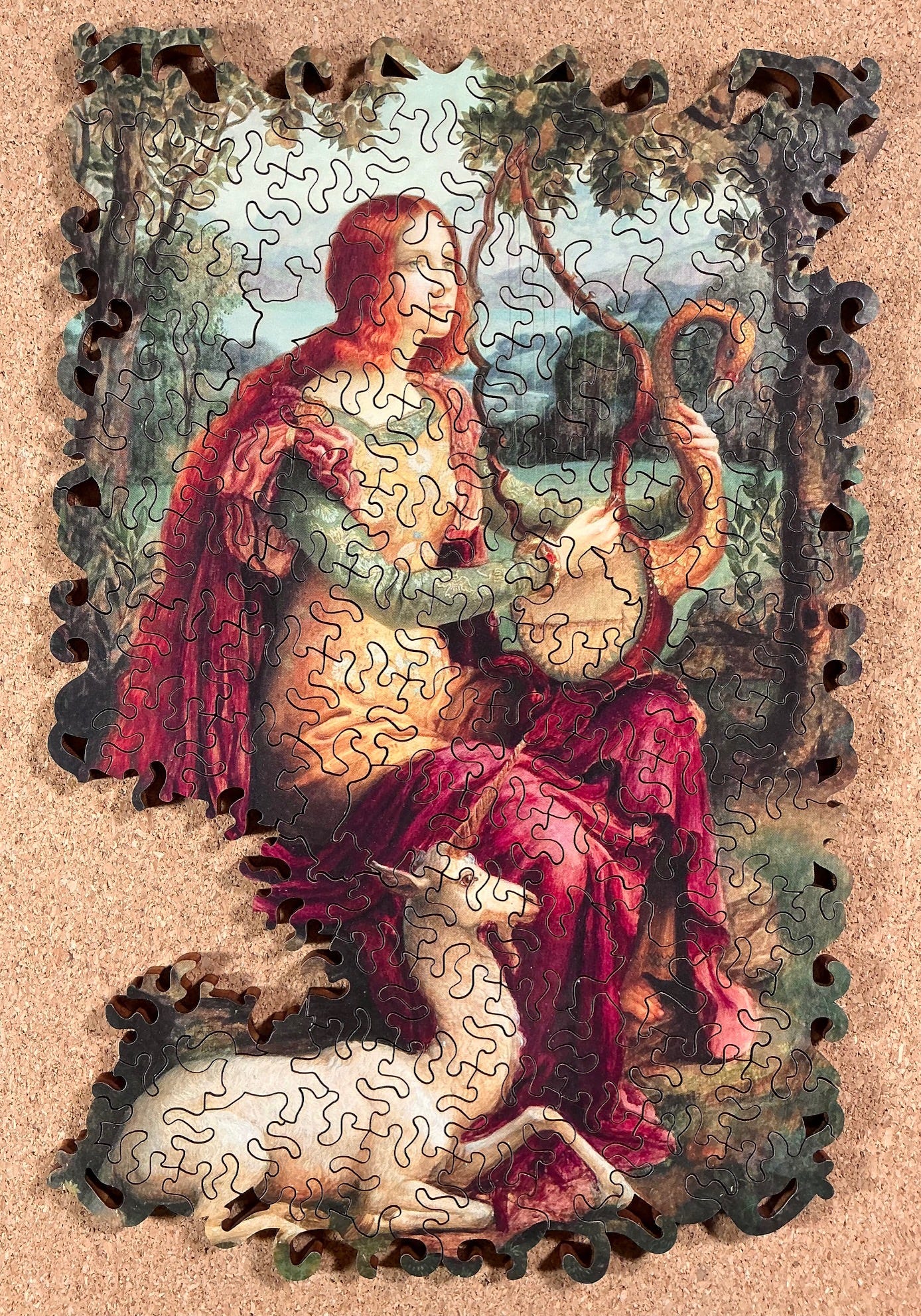

Armond Point Unicorn (Artifact)

cutting designer – Jef Bambas puzzle released May 2020

catalog listing “a bit harder than average”

101 pieces 24 x 16cm ave. 3.1 cm²/pc 5mm 3ply

6 unicorn figurals tendril connectors irregular border with dropouts

artist – Armond Point (1860-1932) painted in 1898

The descriptive name for this 1898 painting by the symbolist French artist Armond Point is A Lady with a Unicorn. According to this site (lightly edited):

Born in Algeria to a French father and Spanish mother, Armand Point arrived in Paris in 1870 at the age of nine as an orphan. He won several prizes for drawing at school, and in 1879 returned to Algiers, where he began painting Orientalist subjects. One of his works was accepted at the Paris Salon of 1882, the first of a number of Orientalist paintings he sent to the salons over the next few years. [Note: For my research on orientalism and the Salon see here under The Slave Market.]

Returning to Paris, Point had his first one-man exhibition at the Galerie Georges Petit in 1889, showing paintings influenced by the art of the English Pre-Raphaelites and the symbolism of the Middle Ages.

In 1891 Point settled in Marlotte, in the forest of Fontainebleau to the south of Paris, in a large house and studio where he was to work for almost forty years. In 1893 he exhibited a number of pastel drawings … at the Societé Nationale des Beaux-Arts, to considerable critical acclaim. . . .

Following a trip to Italy in 1894, and exposure to the works of Sandro Botticelli and other Renaissance masters, Point changed his style radically. After his Italian sojourn, Point’s paintings attempted to reconstruct the techniques and palettes of the Italian painters of the 15th century, taking the work of such artists as Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci as exemplars.

Inspired by the precepts of William Morris, in 1896 Point established a crafts studio in Marlotte. Entitled Haute-Claire, the atelier employed artists and craftsmen of many different nationalities, and produced jewelry, glass, pottery and other objects, many after Point's own designs, until it was closed in 1916.

Here is an artsy view of the puzzle and its image:

Here are examples of other works, also named La Dame à La Licorne (Lady with a Unicorn) that were made by Armond Point and his studio only one year after the image in this puzzle.

This puzzle was designed by author and illustrator Jef Bambas who is also known for his graphic novel series Model:A.

Although the pieces for a small puzzle like this one (111 pieces) don’t really need to be pre-sorted I did it anyway, mainly out of habit:

I began with the few pieces that included some blue sky:

Again, being able to complete the face first was a treat, giving the puzzle a personality even though I had not made much progress at that stage. The pale flesh tone led me down to an ornate green collar and sleeves and golden dress, and the white pieces became an quick-to-assemble unicorn. I could tell that I was exhausting the pieces where the uncommon colours would enable this quick progress.

The pieces that were left were mostly either a fairly bright maroon-red colour or rather drab green foliage. I began with the red and very soon was able to place the unicorn in relation to the woman. That felt like quite an achievement. I had done such a good job of forgetting what the complete image would look like that I was surprised that it turned out to be in portrait rather than landscape orientation.

Then it became just a matter of expanding my way outward, switching back and forth from red to green, and from one side of the puzzle to the other. I figured out that pieces with drop-outs would be edge ones, and many of them tended to be elongated compared to the squarish mid-puzzle ones, which helped.

For its size this puzzle was a bit challenging, mainly because of the sprawl of the tendril pieces. But, as its mere 101 pieces suggest, I would still put it more towards the fun end of the challenge-fun spectrum. That perfectly matched my mood so it was an enjoyable build.

My only complaint about this puzzle is that the figural pieces look too much to me like when my daughters were young and their favourite toys were My Little Ponies. They don’t look like what I think “real unicorns” should look like. I wonder if puzzle designer Jef Bambas played with those same toys when he was young?

Fisherman’s Cottages (Ecru)

cutting designer – David Figueiras released 2019

catalog listing “a bit harder than average”

158 pieces 18.5 x 23.5 cm (7.5” x 9.5”) ave. 2.6 cm²/pc 5mm 3ply

13 figurals tessellation-like triangular cutting irregular edge

artist – Allen Gilbert Cram (1886-1947) undated

I have assembled this puzzle three times now. The first was way back in April 2022 soon after I first discovered wooden puzzles, and the second was last April when I did it with my daughter Wendy while visiting her in in Kingston, Ontario. This third time was back here in Victoria, motivated both by a desire to take assembly photos but mainly to compare my reaction after I discovered that I had written about it previously.

This was just my sixteenth wooden jigsaw puzzle. That was before I began this newsletter/blog but shortly after I had begun to post puzzle reviews in the Facebook group Wooden Jigsaw Puzzle Club. I had forgotten that I had written about it there but here is what I wrote about it back in April 2022 (lightly edited):

This is the first Artifact puzzle that I have assembled, and is the also smallest one I have done to date. Artifact calls it “a bit more difficult than average”. Even after having been warned I found it to be somewhat more difficult than I expected from a puzzle with only 158 pieces.

For a brief time near the beginning of the assembly I tried to assemble it without putting in the whimsy pieces; i.e., treating their locations like drop-outs. That was a tip I had read from someone in this group as a way to make a puzzle more challenging. It’s a good tip, and I’ll try it again on an otherwise-easy puzzle, but I soon abandoned that approach for this one – it definitely tipped my enjoyment into the frustration range.

The challenge came partly from the no-edge design, partly from the non-distinct foliage in the upper half of the picture, but mostly because of the elaborate three-sided cutting of the non-whimsy pieces. Despite this, however, I was able to complete the puzzle without looking at the picture, and I got a feeling of pride in being able to do so.

Despite the fact that this is a colourful painting the colours seem muted. The dark colours do not get as dark as they probably are in the original painting, and the bright colours do not seem rich. I think that the muting is due to the matte (non-shiny) printing of the picture which is an intended feature of Artifact’s Ecru puzzles.

My artificial lighting is mediocre at best and I can see the value of matte printing for puzzles. But this one has made me aware that depth of the dark colours and vividness of the bright ones might be among of the features that I appreciate most in impressionist paintings. I’ll now keep this factor in mind when I am considering buying puzzles where the image would seem to require deep darks and vibrant colours.

This is clearly a well-made product that shows why Artifact has a good reputation. Even the sturdy magnetic box shows that it has a right to call itself “heirloom quality.” One little thing that I especially appreciate is that the box itself is no larger than it needs to be to hold the pieces – a real benefit because my storage space is getting very tight from my recent puzzle spending spree.

Turning the puzzle over one can’t help noticing that it has more scorching than usual. My first thought was to think of this as a flaw since it doesn’t look at all like a hand-cut puzzle. But as I looked at it I soon came to think that the back-view looks better this way, so maybe it is an intended feature. [Update: in replies to this posting people told me that this backside scorching is definitely not intended, but it is better than previous Artifact puzzles. Since then I have come to accept backside scorching as being acceptable even in premium-priced puzzles.]

On balance, this puzzle was slightly too challenging for me to call assembling it a fun experience. But that is not a criticism of the quality of this puzzle, nor of Ecru puzzles in general. It is an indication that my personal puzzling abilities are not yet quite comfortable with a puzzle that Artifact rates as “a bit more difficult than average.” But I’ll definitely take this challenge on again as my abilities develop.”

Now having assembled it again (without having re-read that early review beforehand) I am pleased to say that I think that I nailed it with my explanation as to what makes it a challenging puzzle. The ornate tessellation-like cutting of the non-figural pieces combined with the very loose brushwork (especially of the tree foliage and sky make this a challenging puzzle for its mere 158 pieces.

What I called “no edge” is what is commonly called irregular edge, and it too is of a style that adds to the difficulty. Irregular edges are different from shaped puzzles in that they preserve the overall dimensions of the painting, but some of them are just waves or have sufficient predictability that they do not significantly add to the puzzle’s difficulty. In this case, their short curves are similar enough to the cutting of the other pieces that only the fact that they do not have a triangular tessellation-like shape of the many of the interior non-figurals is a clue that they are either edge pieces or adjacent to a figural.

However I was being more-than-a-little unfair to be critical of the colours, and in blaming it on the matte printing. My comments back in 2022 were shaped by my limited experience at that time, and the fact that I had just assembled four puzzles in a row that had particularly bright printing including StumpCraft’s directly-on-wood UV-printed Bursting Blooms. Now that I have better task lighting and more puzzling experience I see that the same puzzle is actually quite well-printed. Also, I have come to think that the back of the puzzle is more attractive and interesting with its scorching than it would be with less-visible cut-lines.

Now that I have assembled the puzzle three times I would have to say that Artifact’s description of it as being “a bit more difficult than average” is an understatement. Thank you to the puzzle designer, David Figueras, for the mercy of having included 13 figural pieces in this small puzzle to aide in its assembly!

Now on to my assembly walk-through. Based on my previous experience, both almost three years ago and last April, I knew that this puzzle would be challenging and that the very loose brush strokes and colours in the tree canopy would be a significant part of that challenge. I began by trying to build the foreground and the buildings in the middle-ground. My progress to this point mostly came from shape-matching around the silhouette pieces.

After a burst of progress:

And another one:

This next photo may look like I’m halfway home but I knew from experience that the tree-tops against the sky would be the most challenging part of the puzzle. In each of my previous assemblies it got to a stage that looked like this, with the bottom half complete and no progress at all on the top half. But at least now there would be only about half the number of loose pieces to rummage through looking for placements.

Considering that there were probably only about 70 pieces left it was fairly tough slogging the rest of the way.

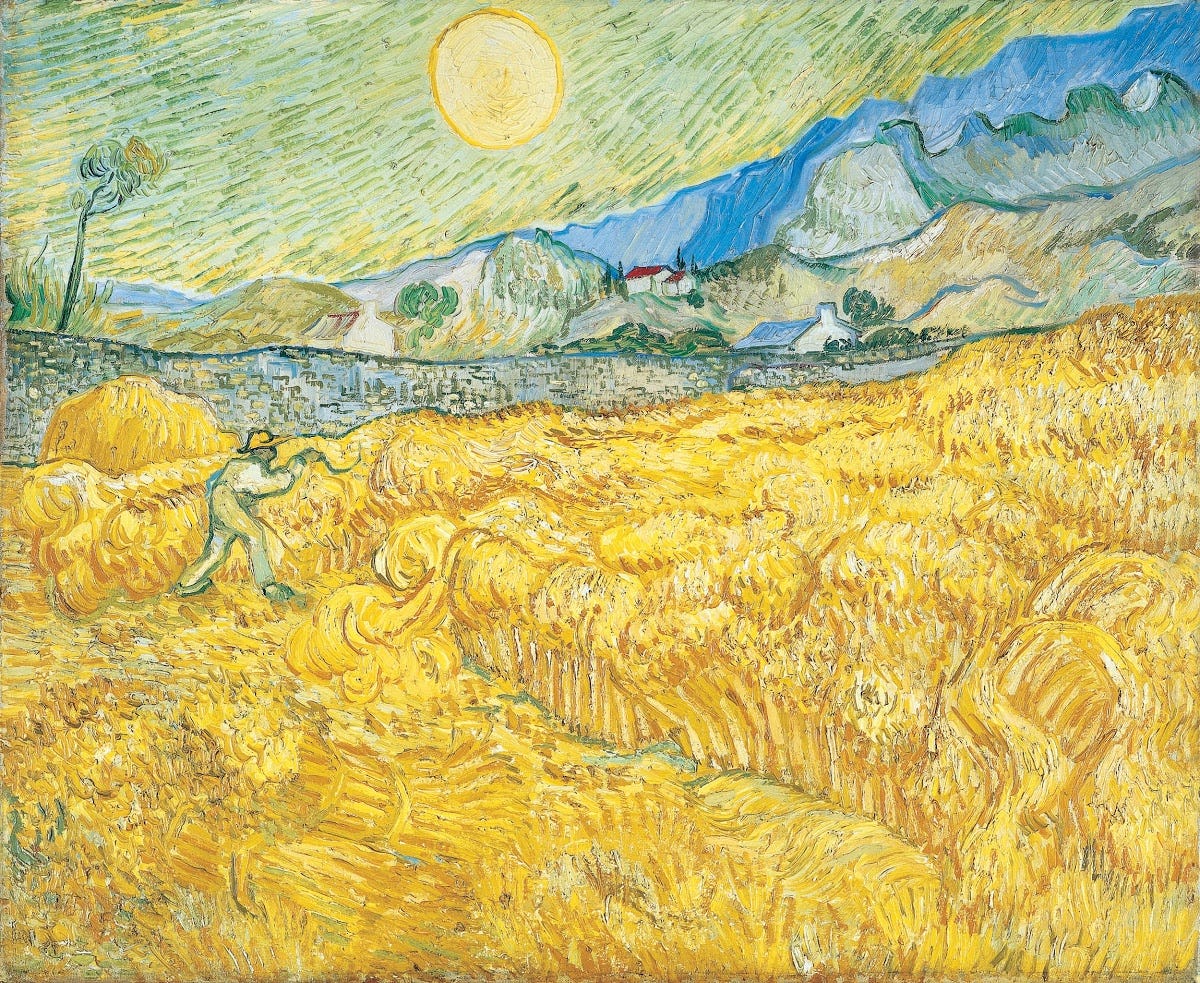

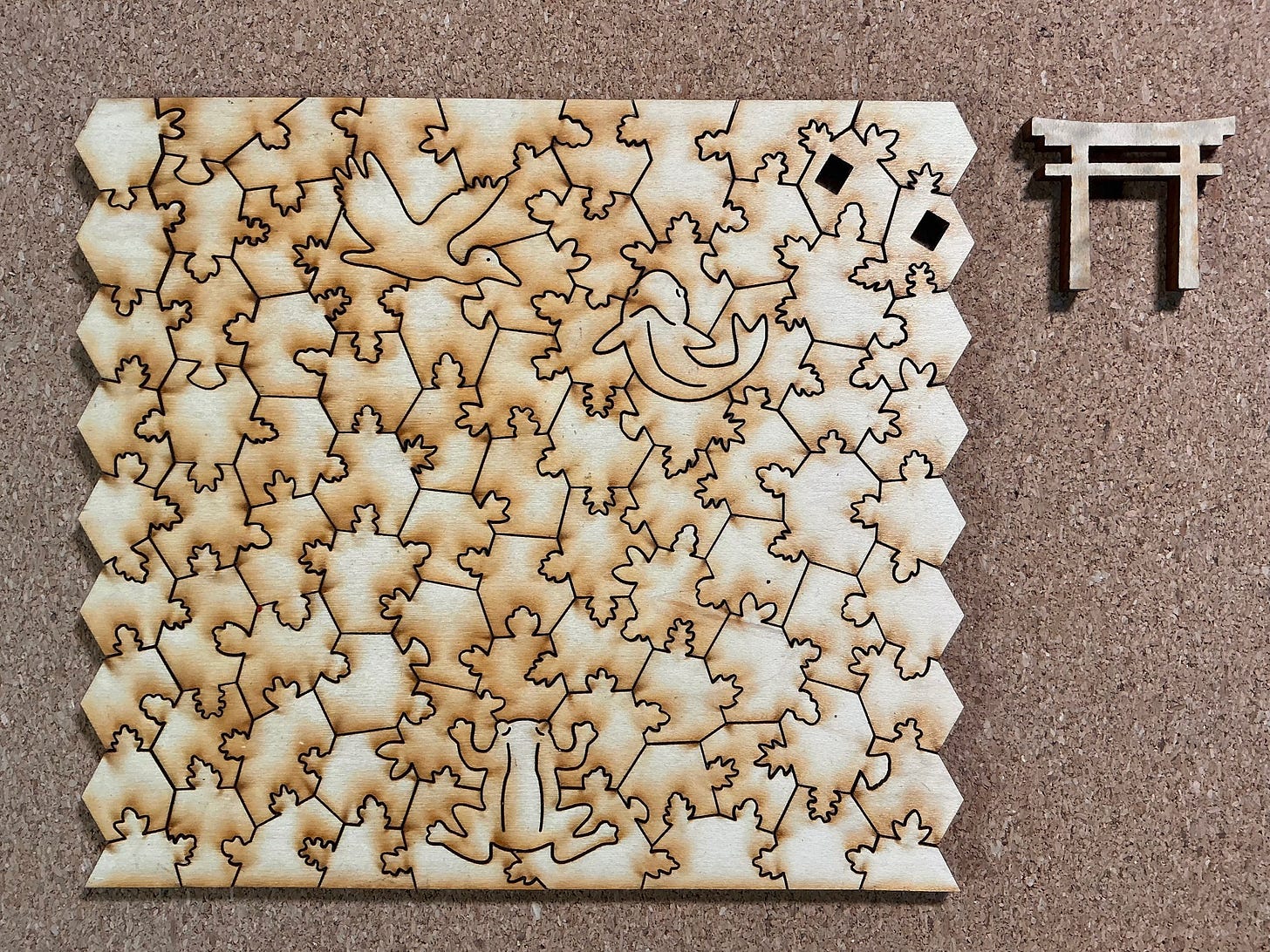

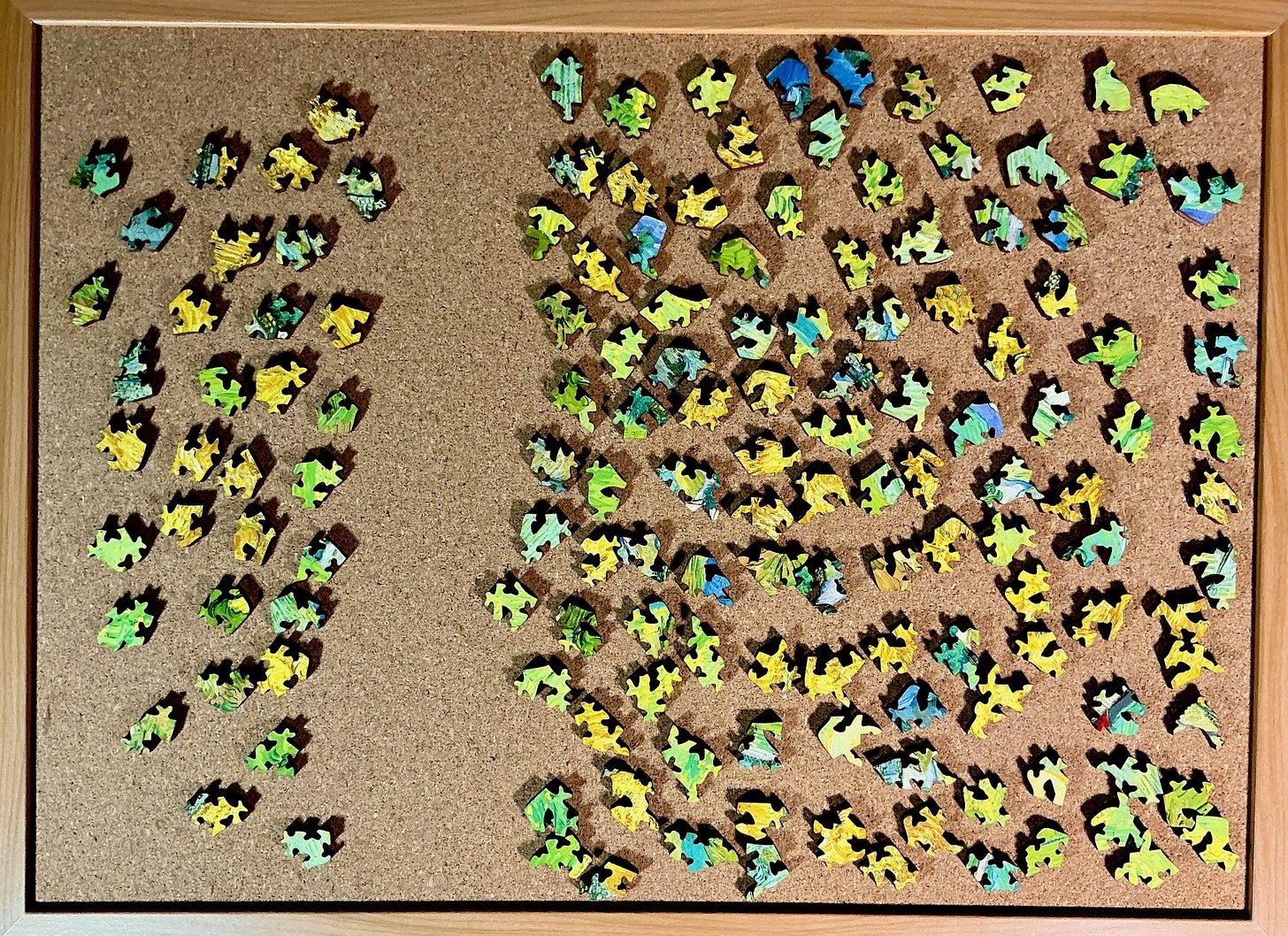

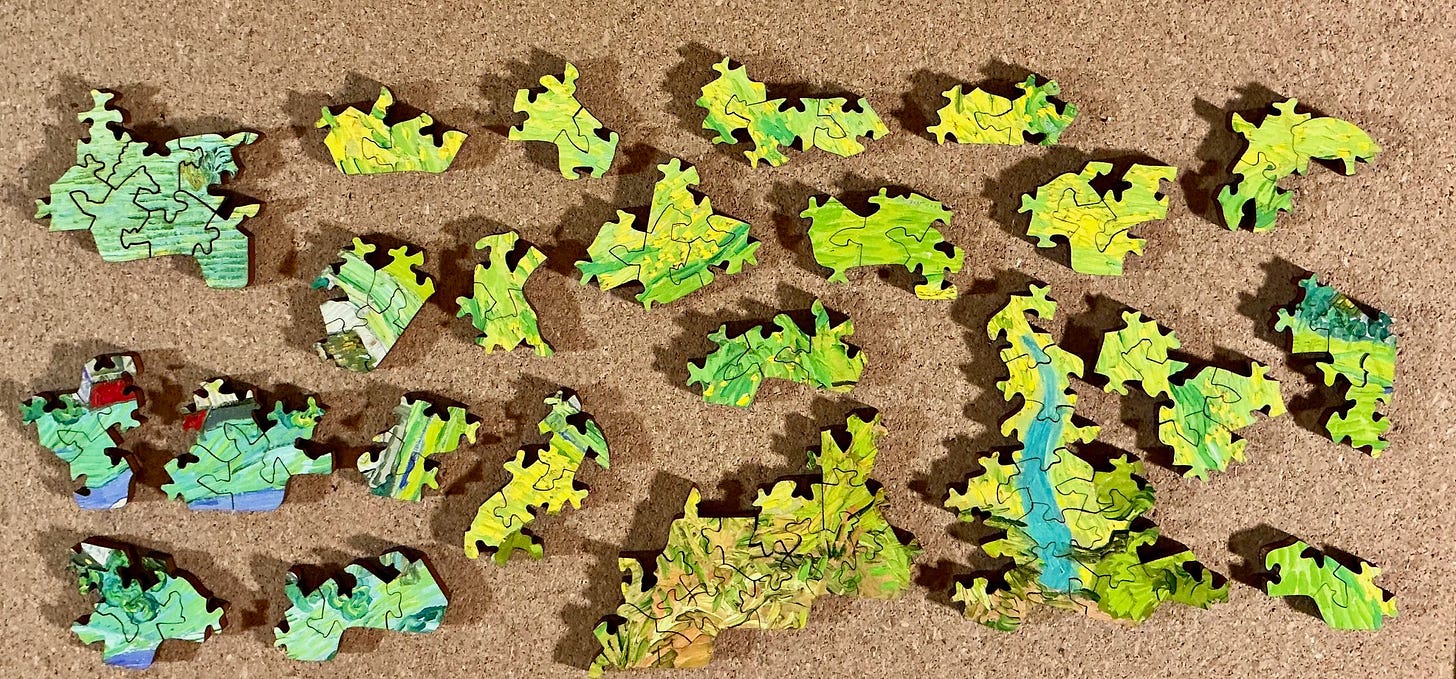

Van Gogh Landscapes Double-sided (Artifact)

cutting designer – Tara Flannery puzzle released in 2016

catalog listing “fairly challenging small puzzle”

150 pieces 18 x 23cm 2.8 cm²/pc 5mm veneered poplar

26 figural pcs pentagonal pieces various connectors irregular border

artist – Vincent Van Gogh painted 1889 and 1890

Both of the landscape paintings on the two sides of this puzzle were painted by Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) in the final years of his short troubled life.

Van Gogh produced many paintings of this same viewpoint in 1899, which was from out of the window in his room at the Saint-Paul de Mausole mental hospital where he voluntarily lived for a full year. He was not restricted to that room but he did like the view it gave him over the top of the institution’s walls.

In a letter to his friend Émile Bernard he wrote that he undertook this painting to deal with the “devil of a question of yellow.” In a separate letter to his brother Theo he wrote:

I see in this reaper – an undefined figure, struggling in the intense heat like the devil to finish his work – I see him as an image of death in the sense that the humans are the corn that is being cut down. So it is, if you will, the opposite of the sowing that I tried earlier. But this death is not sad, it takes place in bright light with a sun that covers everything with a light like pure gold.

During his time in Saint-Remy Van Gogh painted some of his most famous works, including The Starry Night, The Almond Tree Branch in Bloom, and The Iris. But he requested his release on May 16, 1890, despite evidence of mental collapse. He believed his stay at the asylum was not helping him and he longed to paint new and different landscapes.

After leaving the mental institution Vincent moved to Auvers-sur-Oise to live as a private patient with a doctor and amateur impressionist painter who had been recommended to Theo by the artist Camille Pissarro. Vincent was already familiar with the countryside there, where the landscape and buildings reminded him of his childhood home in the province of Brabant in the Netherlands.

Les Vessenots in Auvers was painted during a frenzy of creativity shortly after he arived there. It is the view from Van Gogh’s doctor’s house. According to the curator of the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, which owns and displays this painting:

The narrow colour range—mainly bright greens and yellows—and the nervous, agitated brushstrokes following a repetitive, undulating rhythm, are characteristic of the artist’s work in his final period.

Van Gogh painted a large number of landscapes in the weeks before his death, always working outdoors. By that time, he was prey to all manner of conflicting moods: the vast expanses of fertile cropland gave him a sense of freedom, but at the same time intensified the feeling of melancholy and loneliness which would eventually lead to his suicide.

I didn’t know any of that about the images while I was assembling the puzzles. I wanted to discover the artwork during assembly so, as usual, I had covered up the images on the boxes and I didn’t do the research until after the assembly was completed.

I can’t recall what possessed me to buy this two-sided puzzle. I’m not particularly attracted to that way to make extra difficulty, but it might have been that I liked both of these images and with only 150 pieces it seemed manageable. I had not realized that in addition to the two-sidedness this puzzle would have added cutting trickery courtesy of designer Tara Flannery. It turns out that this is another variation on tesselation, this time based on Cairo pentagonal tiling, with an irregular edge and with only three figural pieces to moderate the challenge. All-in-all, a very appropriate cutting design for a very complicated artist.

Since there were only 150 pieces I used my small cork-board for assembly. My first impression when I began sorting the pieces was that the connectors were primarily “earlets” so when I saw connectors or voids that were shaped like horses hooves, or in a few cases, horse heads, I thought that they must be related to whimsies. I began separating those out.

As it turned out, there were no horse whimsies. The hooves and heads turned out to be connectors and the hooves were the second most-common style! So along with the third most-common type (that I called “springs”) my hoof-based sorting turned out to be the vast majority of pieces (on the right on this photo.)

I tried to work with that sorting but made almost no progress. Since I did not know what the images would be I thought that the abundance of yellow pieces meant that some part of one of Van Gogh’s landscape scenes must be fields in Autumn so did a complete re-sort. I checked both sides of every piece and put the yellow pieces on the right side of my board instead:

Well, I was correct about yellow being fields, but in one of the puzzles the yellow fields comprise the majority of the image. Oh, well. I began to work with this sorting and made some slow progress.

It turns out that one nice thing about a two-sided puzzle is that when I connected two pieces together if I wasn’t sure about the placement (and there were a lot of close-fits!) I could just turn them over to see if there was confirming evidence of the match. When I did so I noticed that the image on the other side seemed to have larger brush-stroke clues than the yellow side. In fact, the brush-work of the yellow turned out to be particularly bad about giving clues.

So I did a third round of flipping and sorting, but keeping all of the now-unseen yellow pieces on the same right-hand side of the board. Knowing that they all must be in the same yellow region of the unseen image was, in itself, a help for narrowing down of which connectors might match with which sockets. It turned out that the back sides of the yellow pieces were also mostly the same colour: They were green now, but at least the brush-strokes were more prominent.

By the same logic, I knew that the pieces on the left-hand side of my assembly board did not have yellow on their back-sides, so that too helped narrow the search for matching “outie”connectors with their proper “innies.” Those darn hoof-shaped connectors and sockets sure were eye-magnets and they were hard to match! Despite the fact that they were so abundant I used an assembly trick that I have only used a few times (in desperation) before.

Still maintaining my board’s left-side and right-side organization I separated out the pieces with hoof connectors and sockets and sorted them based on if they were bent to the left or the right. Similarly, I sorted and organized the pieces with horse-head shaped connectors and sockets. With all of this organizing I began to wish that I had used my larger assembly-board instead of my small one for this 150 piece puzzle. After three complete rounds of flipping and sorting my main feeling was: “Thank goodness this puzzle has so few pieces!”

But at least all of that re-organizing was paying off. Here are my resultant islands of two or more pieces:

And here is the whole assembly board at that stage:

It took quite a bit of trial and error, as well as turning pieces and islands over, to get to here . . .

. . . but only a few minutes to put together some large sub-assemblies (islands) to get from there to here:

Not surprisingly, a lot of my islands and loose pieces that had been on the left-hand side of my puzzle-board (i.e., the ones that did not have yellow on their back-side) were upside-down and I had not been seeing the “village” pieces.

Also, some of the yellow pieces and islands – the ones with broad, smooth brushwork that were interspersed with pale green – actually did belong on this predominantly-green side. Once I readjusted my brain and did more flipping to look for them my progress moved along quickly because of my abundance of moderate sized islands.

Having printing on both sides does indeed considerably add to a puzzle’s difficulty. I suppose that I would be able to do this puzzle better next time because of what I have learned from this assembly, and if I were to assemble more of this type of puzzle I would probably learn more techniques to deal with the extra dimension of challenge. But I can’t really say that I enjoy double-sided puzzling and this doesn’t make me eager to attempt the six-sided puzzle that I picked up at a garage sale last summer for $5.

Hi, again, Bill. Your well-put response to what I wrote is very thorough, thanks. In particular, your response has included mention of ". . . another aspect of puzzle-making that I like to acknowledge when it is particularly well done. . . ." That, my friend is what you do and have done again and again since starting your blog—making me aware of one aspect, after another, after another of the craft/art nature of the puzzles you study and collect.

Regards,

Greg

I had a minor epiphany while reading your latest posting about wooden jigsaw puzzles, Bill. I call it a minor one only because it concerns something that should have been obvious to me long before today; namely, the puzzles you assemble, study, and treasure are each two works of art simultaneously.

When I've owned jigsaw puzzles in the past, ones of the more ordinary, cardboard variety, especially ones that built up into images of some famous painting or some especially lovely scene, I've tended to think, upon their completion, something along the lines of "Wow, it's great to see and and recall to mind this masterpiece of a picture—I'll leave it intact awhile before boxing the puzzle up again and returning it to my puzzle shelf." Aside from possibly taking minor notice of the thickness or tight fit of a particular puzzle brand's cardboard, my appreciation of what I'd just assembled was nearly all for its picture.

Well, it has struck me that when you describe at length the delight you can take in the feel of puzzle pieces, the clever design of whimsies, incredible subtleties of puzzle manufacture, etc., etc., that you, Bill have got TWO works of art on your table when you are enjoying one of the wooden puzzles in your collection.

I admire your sensitivity in this regard, Bill. Carry on, Friend. Perhaps, I understood the attraction of your hobby on some level, and did realize that craft was involved; but today, for whatever reason, it suddenly became clearer to me that I ought to think of the folks who make your beloved puzzles, as artists.

By the way, my favourite among the puzzles you reviewed above is Les Vessenots in Auvers, by reason of BOTH Van Gogh's contribution to it AND the contribution of the puzzle-makers. Also, by the way, I rather like two-sided puzzles, myself, though my experiences with them have been limited to doing large cardboard floor-puzzles with my Kindergarten students. If I were still teaching Kindergarten, I might try to buy the six-sided block puzzle from you!

Fondly,

Greg