27. Sr. B’s The Garden of Opportunity

A puzzle review, but mostly this is an essay about the image's Pre-Raphaelite artist Evelyne De Morgan, her husband, and their legacy (about 4500 words; 32 photos)

[Note: Other than as a customer I have no association with Sr.B Puzzles or its proprietors.]

This posting is nominally about a recently hand cut jigsaw puzzle made by the Sr.B Puzzles Workshop in Spain. But actually I spent a lot more time doing the research that its image inspired than on its assembly. I learned a lot about the largely-unknown artist who painted it and her marriage to another unsung artistic genius. Even the story of their biographer is an interesting tale. So I ended up writing this article that is more of an essay about the artists’ lives and legacy than a puzzle review. But I’ll begin with the puzzle:

Introduction – the jigsaw puzzle hierarchy

In general there is a hierarchy of prestige and quality in the world of wooden jigsaw puzzles, and their prices tend to reflect their place in that hierarchy. At the bottom are puzzles that are die-cut in China from 2mm thick basswood 3ply. Those are basically just like cardboard puzzles except that the material is sturdier. Most wood-puzzle aficionados don’t consider them to really be wood puzzles at all despite their material: Two millimetres just doesn’t give a luxurious experience, and die-cutting can’t produce the range of interesting piece shapes that make assembling wooden jigsaw puzzles a distinctively different experience from putting together cardboard ones.

Next up the ladder are laser-cut puzzles, and within this category there is quite a range of quality determined by their presentation, printing, thickness, cutting design and quality of fabrication. In general, higher prices are associated with higher quality.

At the top of the hierarchy are puzzles that are individually designed and hand-cut puzzles made by craftspeople the traditional way using scroll saws and extremely thin (and fragile!) saw blades. These too have a range of quality based on those same factors. The best ones have an elegance that gives their assembly the feeling of being a hedonistic treat.

Sr.B Puzzles Workshop makes hand-cut puzzles that are relatively inexpensive as hand-cut puzzles go but they have that elegance. Based on having assembled this one, and read online reviews about many more, I can highly recommend Sr.B puzzles!

The puzzle - data

The Garden of Opportunity made by Sr.B Puzzles Workshop

artist – Evelyn De Morgan oil-on-canvas 1170cm x 1940cm painted in 1892

cutter and designer - Raúl Barrera hand-cut March 14, 2023

puzzle size – 481 pieces 21.5 x 43.5cm (8½” x 17”) 1.9 cm²/pc 5mm 5ply (poplar?)

price - $238.72 CDN ($175 USD) including shipping

Sr.B Puzzles Workshop

SrB is a small family business in Pioz, Spain comprised of cutter Raúl Barrera and María José who handles customer relations and other business sides of the company. They are both long-time jigsaw puzzle aficionados who met eleven years ago on a puzzle forum. Raúl was an experienced woodworker and nine years ago María encouraged him to take up hand-cutting puzzles.

At first he did so only for their own collection and as gifts. That evolved into selling at craft shows. In 2020 during the first year of the Covid pandemic when such markets could not be held they began selling their puzzles online through their Etsy store SrBPuzzlesWorkshop. Like most hand-cutters they make custom-made puzzles as well as ones made “on spec.” They only make puzzles with fine art images that appeal to their artistic tastes which seem to tend towards Japanese woodprints, Art Nouveau and Pre-Raphaelite paintings.

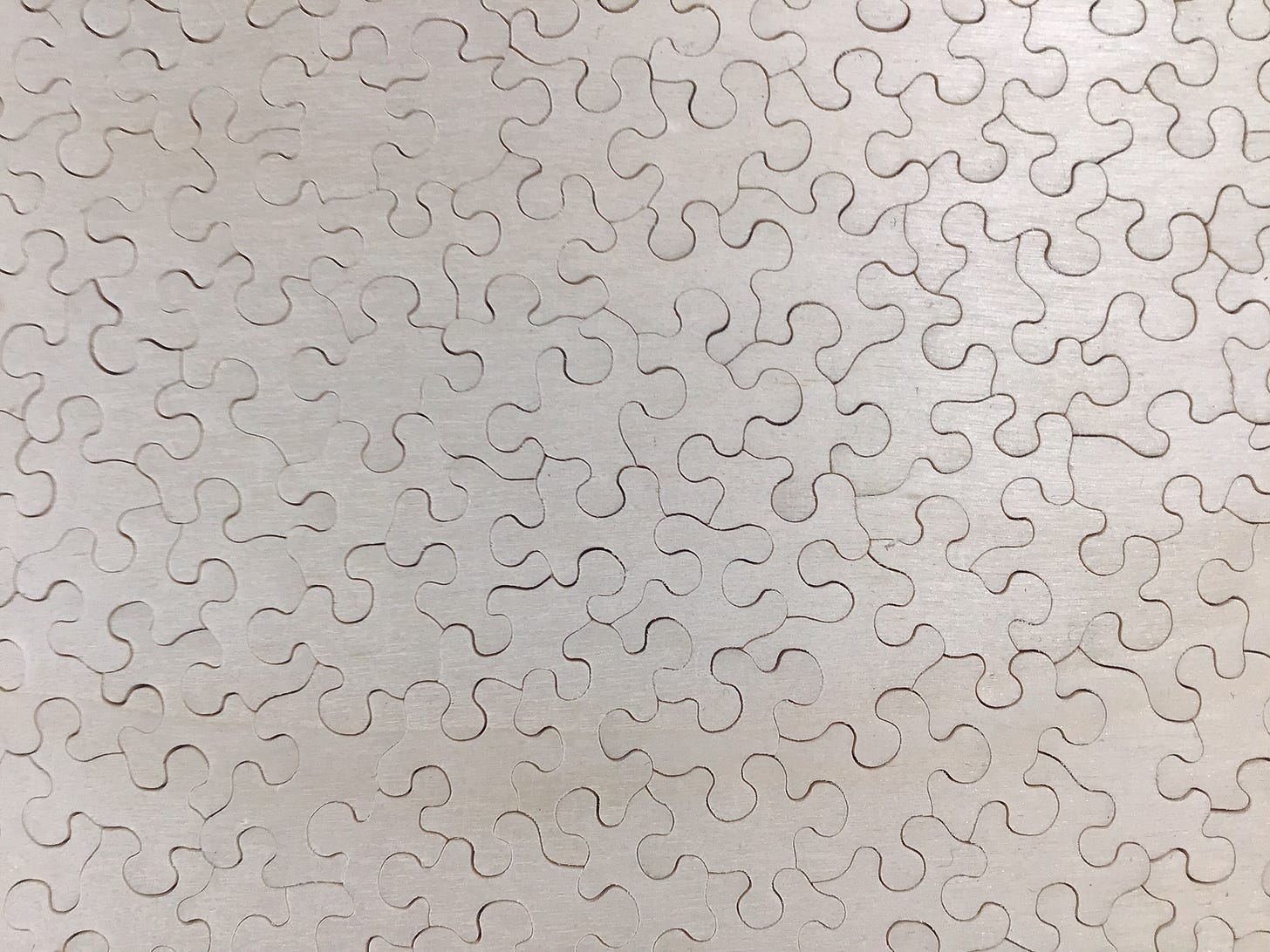

Current vogues in wood jigsaw puzzles seem to be an infatuation with incorporating an abundance of figural pieces (AKA whimsies) that complement the theme of the image, designing creative connectors to complement the theme, and shape cutting the outside edges of puzzles. I appreciate the creativity and fun that those design elements can instill in puzzles, especially ones that are more illustrations than fine art. But in the case of fine art paintings, innovation in the cutting design sometimes draws too much attention away from the painting itself. I presume that is why Sr.B’s house style of cutting does not follow these trends. Raúl’s cutting is quite “old school”.

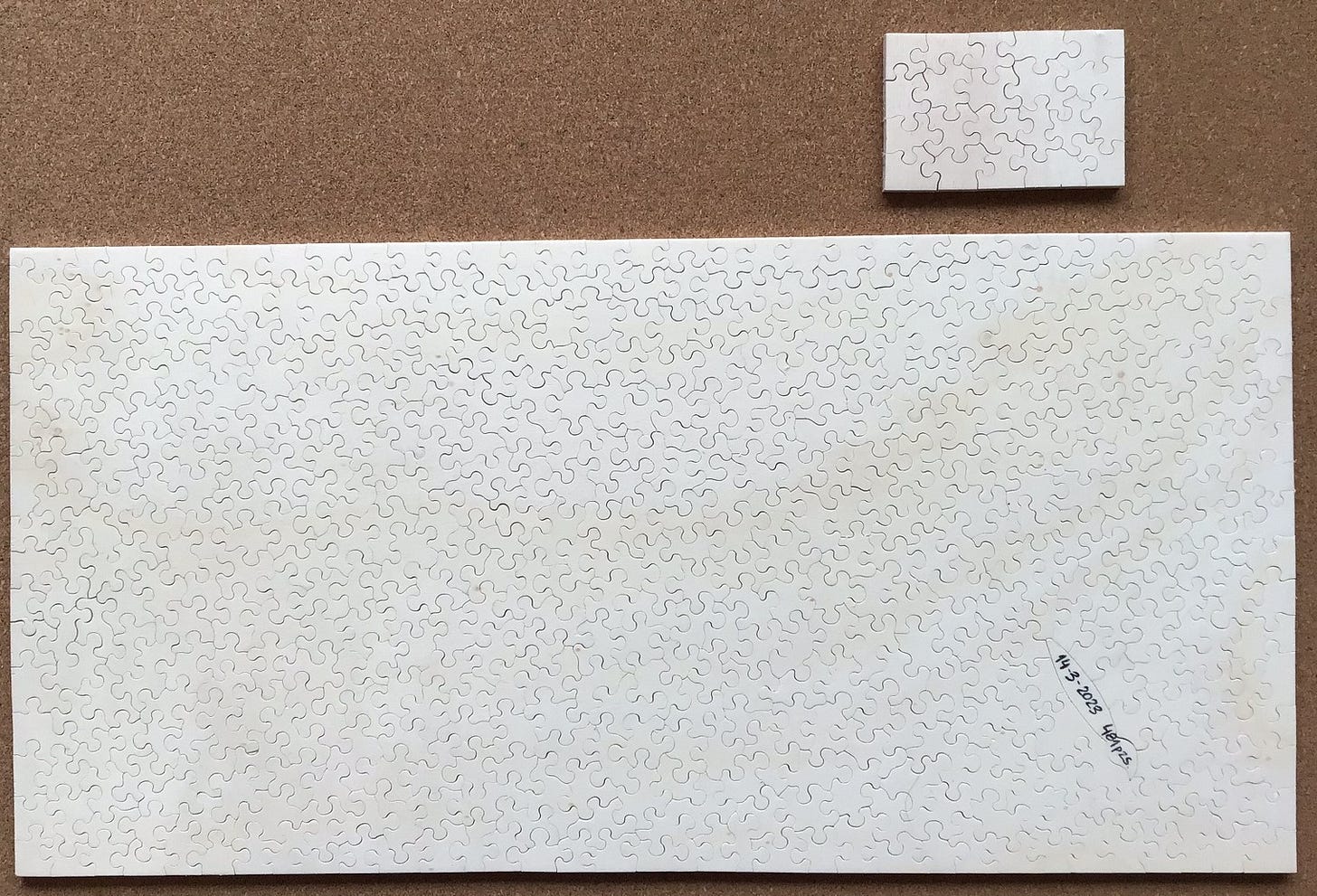

Judging by the many Sr.B puzzles that I have seen online my puzzle is very typical of their style. Other than one signature piece (a paintbrush that is included in all their puzzles) it does not include figural pieces. The cutting is a free-flowing, constantly curving, swirling dissection of the image into interlocking shapes. I have encountered this cutting style before (for example, Perfect Harmony cut in 1933) and have taken to thinking of it as being “baroque”.

Note in the above photo of part of the back of my puzzle that the cutting lines never cross each other to make a four-corner intersection. This baroque style results in a fully-interlocking puzzle that is far more time-consuming to cut than the commonly-used efficient grid style of cutting in which every piece has for sides. But for all its apparent simplicity, including having only one style of connector (rounded knobs), the result is a confusing similarity of abstract-shaped pieces that results in a much greater assembly challenge. I think that the variety of beautiful piece shapes that it produces, without needing to resort to using figurals for added interest, make this my favourite cutting style.

According to the Sr.B website:

Our puzzles are unique pieces. Made with lots of love and we cut them without using any type of guide or pattern … We only do artwork puzzles and we don't repeat the same image in the same size twice, so if you find an image that you love, don't hesitate to buy it or someone will overtake you.

I know from experience that last statement is true. Their newly-released puzzles tend to be snapped up quickly – often within minutes of being posted – so I felt very lucky to be able to buy this puzzle with a beautiful image painted by an artist about whom I was previously unfamiliar.

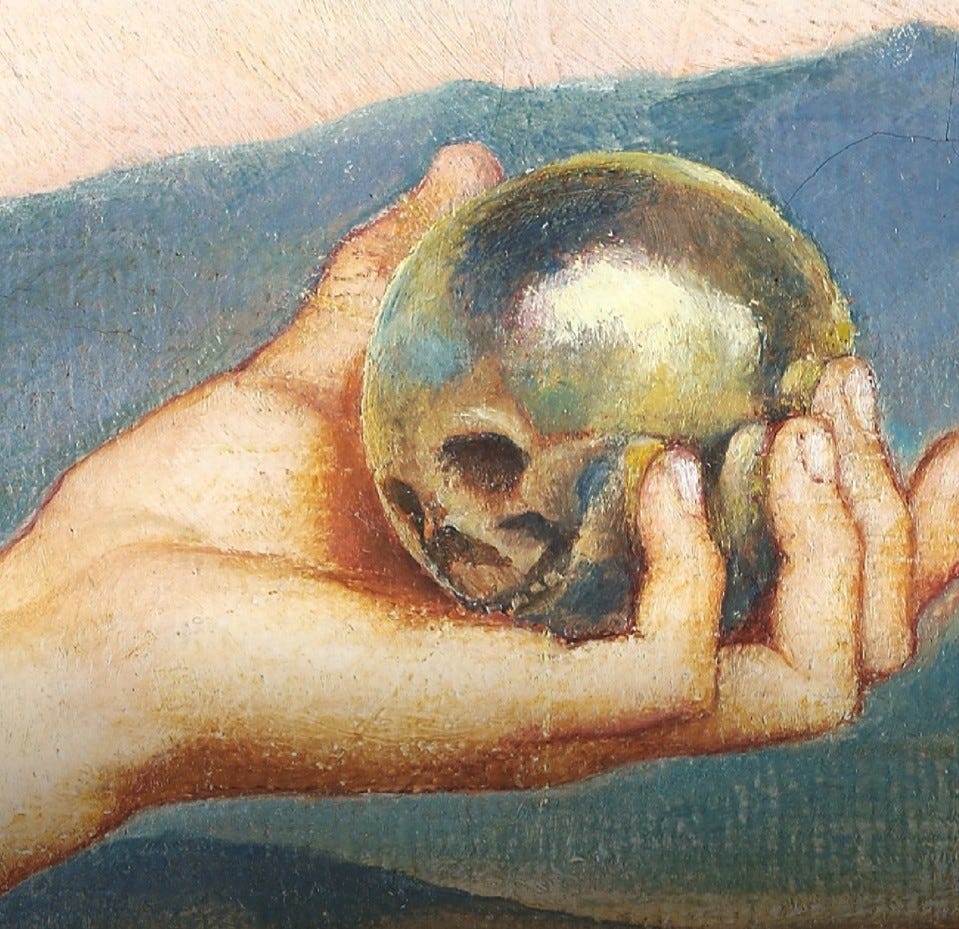

My one regret about this puzzle is that its small size of 21.5 x 43.5cm (8½” x 17”) cannot do justice to all of the symbols and details that Evelyn painted on her two square metres of canvas. For example, in the puzzle I could see the beautiful woman on the left is offering the twins a silver ball. Indeed, although it is off-centre it seems to me that gesture is the focus of attention for the whole painting. Here is a close-up of that ball from a hi-resolution photo of the painting:

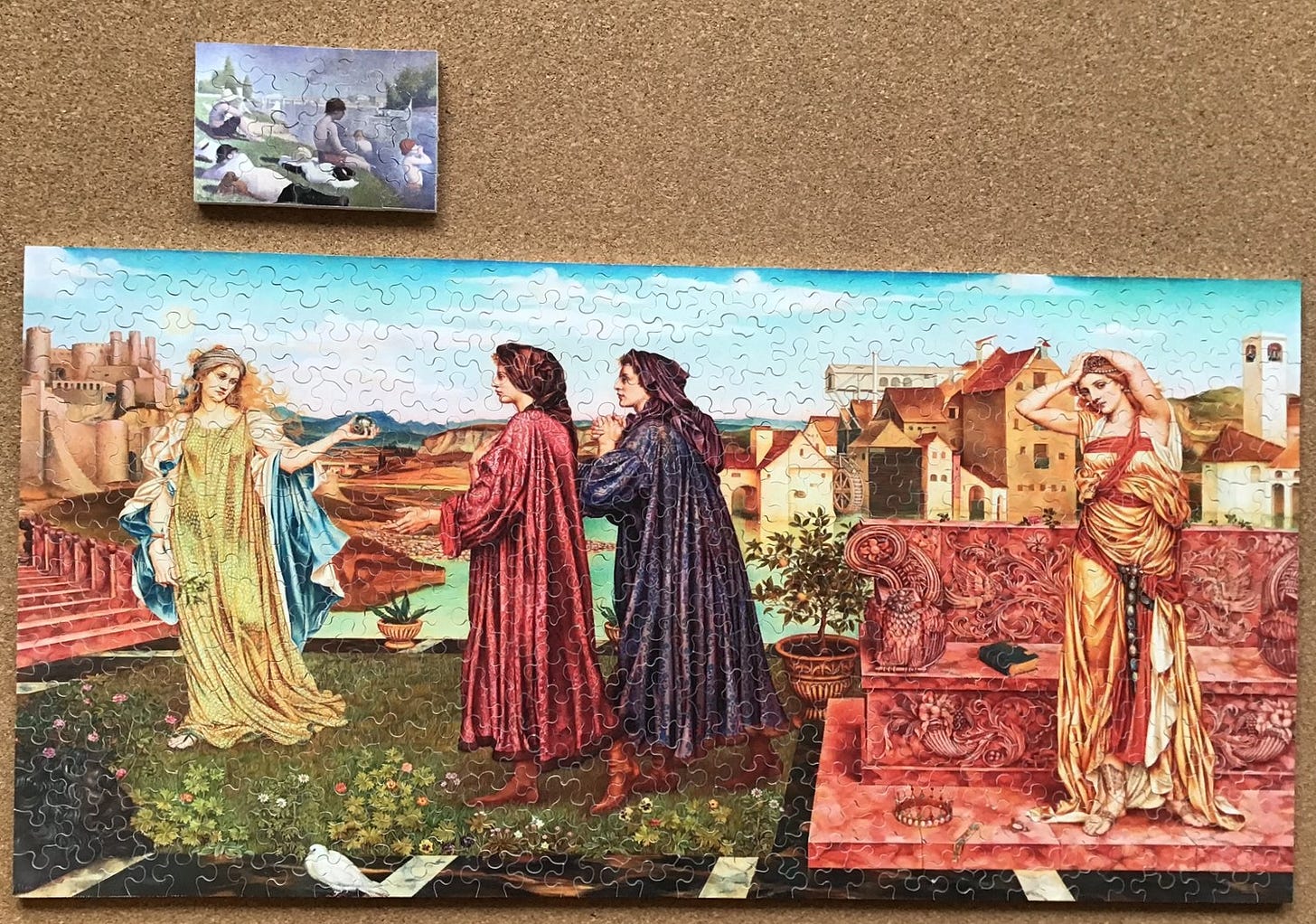

As an extremely truncated puzzle review, suffice it for me to say that this is nevertheless a very high-quality hand-cut puzzle. I really enjoyed assembling it and will undoubtedly do so again. And it was a great value and not much more expensive than a premium laser-cut puzzle with a similar piece-count.

Soon after I began building this puzzle I knew that I wanted another Sr.B puzzle. (It helps that their tastes in fine art overlap so well with mine.) I kept an eye on their Etsy store but have noticed that new postings are not coming up as frequently as they used to. I suspected that was because Raúl was being kept too busy with custom orders. Finally one popped up with a Japanees woodprint image that I really liked, but it was already sold. So I custom ordered a 600 piece (or so) custom version of it and got into the queue. It will be ready in about 10-12 weeks. That’s fine - it should make a really nice Autumn puzzle.

The artist

The image for this puzzle was painted by Evelyn De Morgan (née Pickering; 1855 – 1919.) Evelyn came from a wealthy upper-class family. Her father was a prominent QC (Queen’s Counsel) barrister and her maternal grandfather was the Earl of Leicester. In the manner of the Victorian era she was educated at home by tutors, but unusually for the time she was given the same education as her brothers. That included the study of classical literature, mythology, history and the sciences, as well as learning Greek, Latin, French, German and Italian.

I presume that she was also trained in the “womanly arts,” meaning various forms of needlepoint and watercolour sketching, but oil painting became her obsession from an early age. (Oil painting was definitely not considered a womanly art at the time! Here’s an interesting journal article about that.) Her mother actively discouraged this interest. Her sister Wilhelmina (more about her later) reports that their mother wanted “a daughter, not an artist” and would tip the drawing tutor to give Evelyn harsh critiques of her work in hopes that Evelyn would give up her artistic dreams.

Actually, Evelyn’s parents were prominent art collectors themselves, but with the conservative tastes of the Royal Academy. Evelyn was more inclined to the avant-garde Pre-Raphaelite movement, in which her uncle John Roddam Spencer Stanhope (the bohemian black sheep in her mother’s aristocratic family) was a prominent artist, and to incorporating mystic symbolism in her art.

Evelyn’s mother had the traditional Victorian perspective about the institution of marriage and the importance of young ladies “marrying well.” She wanted her teenage daughter to go to finishing school to prepare for the big event of her presentation to society and to the Queen. Evelyn had no desire for such a “coming out” and would have none of that. Her younger sister (and eventual biographer and biggest supporter) quotes her as having said “No one shall drag me out with a halter around my neck to sell me!” She wanted to go to art school and become a professional artist like her uncle.

Evelyn’s father, however, was supportive of her artistic ambitions and (as recorded in his personal diary) he was the one who decided to pay for her artistic training. After a brief stint at one of the Royal Academy schools he allowed her to transfer to the more progressive Slade School of Fine Art. In addition to that formal training her father also allowed Evelyn to accompany her uncle to spend winters in Florence where she could study the paintings by Botticelli and the other renaissance artists. She also got mentoring from her uncle, and through him she became friends with other Pre-Raphaelite painters like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt.

Through her new friends Evelyn was introduced to Spiritualism, which became a life-long passion. Spiritualism was a social religious movement that thrived from the 1840s to the 1920s. It taught that an individual’s spirit persists after death. For spiritualists, the afterlife is not as a static place. Spirits of the dead continue to learn and evolve and therefore become more advanced than living humans and capable of providing valuable insight regarding moral and ethical issues. The challenge for spiritualists is learning how to communicate with them.

Above is a relatively early painting by Evelyn, made in the early phase of her career when she was 25 years old. According to the De Morgan Foundation:

Death was an increasingly common theme in Evelyn’s oeuvre as time went by. The Angel of Death I is the most overt representation of the subject and demonstrates Evelyn’s spiritualist belief that death is to be welcomed and not feared.

Evelyn depicts the Angel of Death, who is symbolised by his grey hair and scythe, as a beautiful and benign figure, gently comforting the frail female figure he has in his sight. The young woman appears to have had a hard life - signified by the arid landscape behind her. In contrast the way forward is illustrated with a fertile landscape and spring flowers …

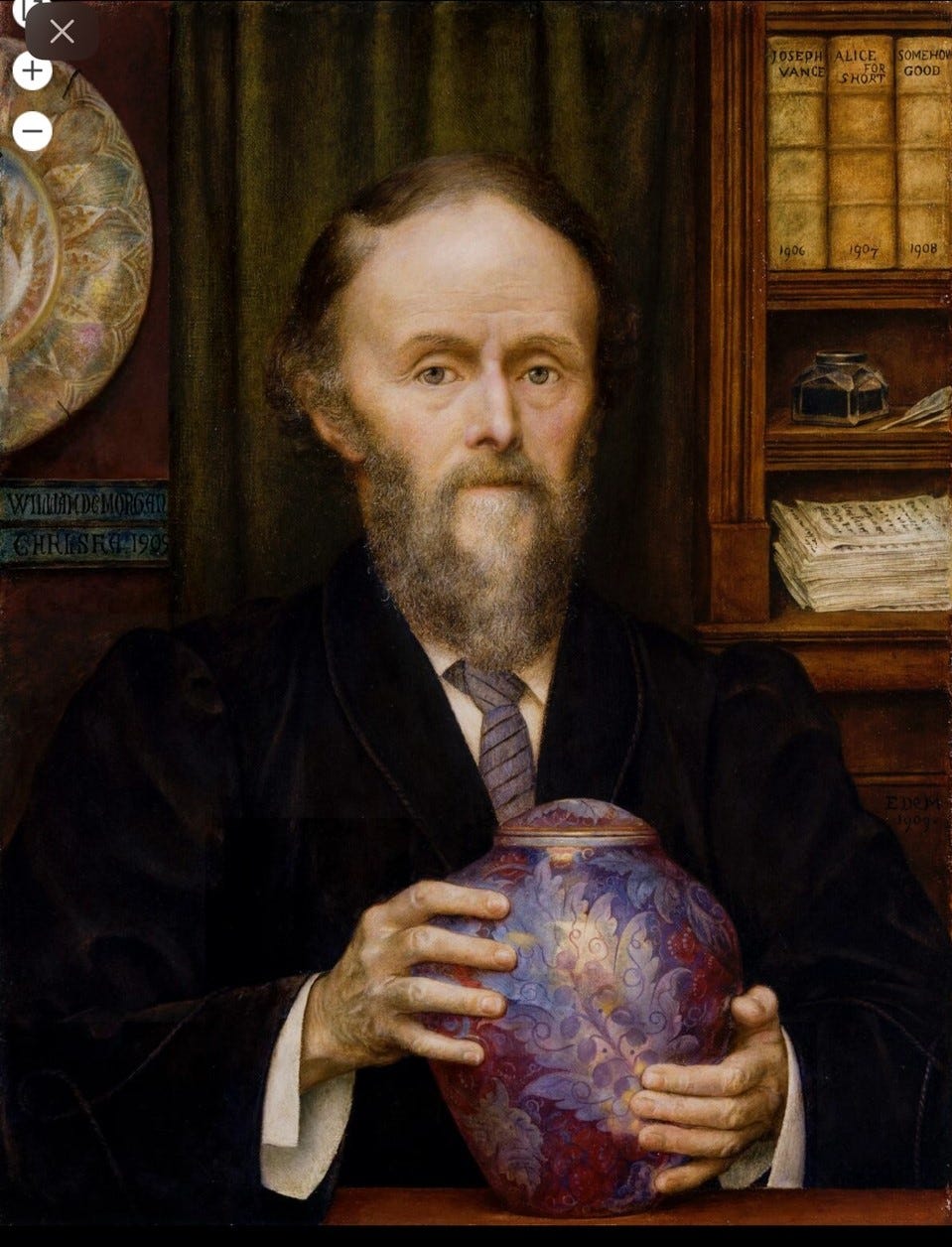

I don’t know if Evelyn ever did have a coming-out presentation to the Queen. She did end up marrying in 1887 (at the age of 32) but not to anyone who she would likely have met at Buckingham Palace, and not to a man who either of her parents would have considered to be an appropriate husband for their daughter. It was to an atheist she met in those left-leaning artistic circles. William Frend De Morgan (1839-1917) was an Arts and Crafts Movement ceramics painter and tile designer who came from a family of social reform campaigners, and was a close personal friend and colleague of the socialist/businessman William Morris. Together, Evelyn and William became what this article describes as “an artistic power couple.”

William had begun his career as a painter trained at one of the Royal Academy schools but early on he switched from painting with oils to painting images on ceramics and tiles using of coloured glazes. That led him to realize that the capabilities of that craft in the Victorian Age were constrained by the fact that sophisticated glazing techniques from the past had been lost. Old pottery and tiles from the Middle East has a lustre, depth and brightness that could no longer be produced.

Through much experimentation William reinvented the old techniques. According to his Wikipedia entry: “… De Morgan mastered many of the technical aspects of his work that had previously been elusive, including complex lustres and deep, intense underglaze painting that did not run during firing.” He also developed a type of clay that resisted cracking from freezing. By the time he married Evelyn he was the undisputed master of that form of decorative art, and it was a time when the decorative arts were much more highly respected than they are in the art world today.

Besides being artists, Evelyn and William were both strong proponents of social reform, especially women’s suffrage and other related issues that would now be called feminism. They were also strong proponents of pacifism during both the Boer War and World War I and advocated for other social issues that are still on the progressive end of the political spectrum. Both were also both deeply fascinated by Spiritualism and are believed to have been the anonymous authors of an influential book about automatic writing and the use of Ouija boards to communicate with the dead.

One thing that William wasn’t was a proficient businessman. His strength wasn’t really even making pottery itself – it was in applying and innovating in the alchemy of their glazes. He began a ceramics business in partnership with architect Halsey Ricardo that produced Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts style ceramics and tiles, but it struggled. Although Evelyn was having the same problems that all woman painters faced at that time in getting their works accepted, she did develop a loyal following of a few wealthy patrons. Sales of her paintings, as well as money from her personal inheritance, were instrumental in helping to stave off the company’s bankruptcy.

The problem with William’s business was that while the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements are highly prized today, at the time they were both short-lived avant-garde artistic styles rather than reflective of classic mainstream tastes. The business did have some important commissions but the main problem was that its styles were fashionable for only a short period of time. Around the turn of the 20th century sales continued to fall, and due to ill health William needed to restrict his role to design and technical problem-solving.

In 1906 William and Evelyn figuratively saw the handwriting on the wall (probably written there by a spirit ;^) and the partners sold the business. William said: “All my life I have been trying to make beautiful things and now that I can make them nobody wants them.”

For Evelyn that meant she no longer needed to sell her paintings to try to keep the business afloat. I can’t imagine that she ever got over the frustration of being an under-appreciated woman artist, but she no longer needed to have commercial considerations influence what she chose to paint. As I understand it, after the sale of the business she never sold a painting again (although she did occasionally donate them for charitable causes.) Her art had always been allegorical, with themes and symbols that related to social and women’s issues, but now it got more mystical and dark. She continued to paint symbolic images in the increasingly out-of-favour Pre-Raphaelite style.

Actually, after William’s retirement the family was financially quite well off, mainly because in 1906 Evelyn (and possibly the spirits) encouraged the retired decorative artist to turn his attention to writing. His first novel, Joseph Vance (subtitled An Ill-Written Autobiography) was an instant international hit and he followed it with six other best-selling novels. He quickly became much more famous and wealthy for his writing than he had been for his ceramics.

William died in 1917 and Evelyn in 1919. They were soon forgotten. Britain had no abiding interest in any of the formerly avant-garde artistic styles with which they were associated, and even William’s recent bestselling novels seemed hopelessly old-fashioned after the horrors of The Great War.

The story might have ended right there except for one person who made it her mission to keep their memory alive, and social changes that began in the 1960s which brought renewed appreciation for their artistic styles and for them personally. The one person was Evelyn’s younger sister Wilhelmina Stirling (also née Pickering; 1865-1965.) Wilhemina was an author who was also well aware of the prejudices against women professionals – most of her writing was published under A.M.W. Stirling or the pseudonym Percival Pickering.

She greatly admired both her sister (10 years older than her) and her husband, both as individuals and as artists. Following her sister’s death in 1919, Wihelmina had to battle with their brother Spencer, the executor of the De Morgan estate, to acquire the large cache of working drawings and sketches and writings, as well as the finished works that they chosen to keep, including a significant portion of Evelyn’s lifetime production of oil paintings. It was not that he wanted them himself. Quite the opposite. He saw those things as “refuse” - not good enough - and wanted to dispose of the lot.

After that she saw herself as the custodian of an historically important trove of artistic treasures and Wilhelmina dedicated much of her remaining long life to being the steward of their memory and of the artistic styles they represented. In 1922 she wrote a (somewhat biased) biography of the couple called William De Morgan and His Wife. She also became a serious art collector who had the same old-fashioned tastes as Evelyn and William. Because those styles had become so terribly out-of-fashion she was able to acquire many further works that had been made by both Evelyn and William, as well as other important Pre-Raphaelite paintings and Arts and Crafts furnishings.

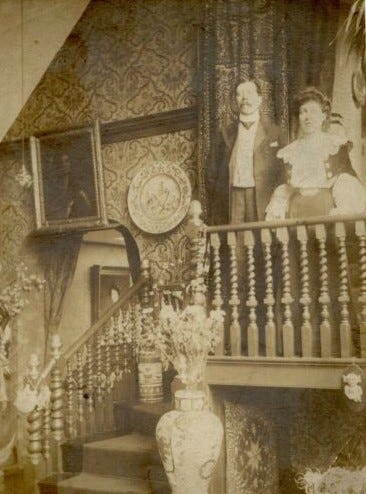

Wilhelmina and her husband Charles Goodbarne Stirling (1866-1948) both enjoyed giving tours of their home to show off their collection and it became a widely-known pilgrimage site for the remaining admirers of those art movements. But the home was not large enough to display many of the prized works in their collection. In 1931 they were able to resolve that problem by gaining lifetime tenancy (for only nominal rent) of a mansion in the historic Battersea district of southwest London that is believed to have been designed by the renowned 18th century architect Christopher Wren.

Wilhelmina loved giving tours of the house and its contents during which she could talk for hours on the artwork she exhibited. And as a Spiritualist herself she could also tell anecdotal stories about the mansion and the various spirits who inhabited it with her. She did this right up to shortly before her death 1965, a mere 15 days before what would have been her 100th birthday.

I imagine that in her later years she was considered to be a very eccentric old lady, living virtually rent-free in an increasingly run-down mansion and a passionate admirer of terribly out-of-fashion paintings, pottery and ghosts. Like her sister she was childless and she feared for the future of her beloved art collection. Shortly before her death she changed her will, providing that all of her considerable estate would go to a Trust to be established for the purpose its collection. I haven’t tried to do any research on how the press reported this news at the time but I imagine that it was somewhat akin to reporting that a rich old lady left a vast fortune to her cats.

That Trust, now known as The De Morgan Foundation, has been active ever since, conserving the collection, acquiring further artworks to complement it (they now own over half of Evelyn’s lifetime production of oil paintings and many of William’s finest ceramic pieces), researching and developing interpretive material, and arranging for their display to the public. The Trust no longer had use of the use of Old Battersea House so for many years that last activity involved operating a small art museum but mainly loaning out artworks for display at various historic sites that had an association with the couple. Loaning items from the collection for display in historic sites is still the major part of their modus operandi but recently they opened a new museum in the east wing of Cannon Hall, the childhood home of Evelyn De Morgan’s mother.

Pre-Raphaelite paintings and Arts and Crafts style decorative items are no longer seen as out-of-fashion. In fact, they are now mainstream and among the most popular 19th century English artistic styles. Ironically, they returned to fashion very shortly after Wilhelmina’s passing in 1965. Pre-Raphaelite art came back into fashion as an offshoot of the “swinging ‘60s” rediscovery of the Art Nouveau style, and Arts and Crafts as a result of renewed appreciation of Victorian era architecture and its decorative arts. Evelyn De Morgan herself has drawn considerable attention from modern feminist scholars and collectors due to her role as a woman artist whose promising career was frustrated by the gender discrimination of her times, and for having flouted the social conventions of upper middle-class women of the day by insisting on marrying a man who would treat her as an equal.

And as for William, he too is drawing attention from feminist historians for the egalitarian nature of his relationship with Evelyn and as one of the leading male supporters of the suffrage movement in Britain. The books that brought him fame late in life are still largely forgotten, but according to an online description of his ceramic work by the Victoria and Albert museum: “With their vibrant colours and captivating designs, the ceramics of William De Morgan … are among the most attractive, recognisable, and enduringly popular decorative arts of the late Victorian period.” See here for a more detailed discussion of William’s ceramics.

This has been only a very abbreviated version of what I have learned about Evelyn’s art in my descent down a research rabbit-hole. There has been a lot written about her, partly due to the work of the De Morgan Foundation but also by art historians and feminist scholars (including in many books about women artists and two new books specifically about her.) To learn more about Evelyn you can start with her Wikipedia entry which includes links to related topics and information sources, or the De Morgan Foundation’s online biography.

The Painting

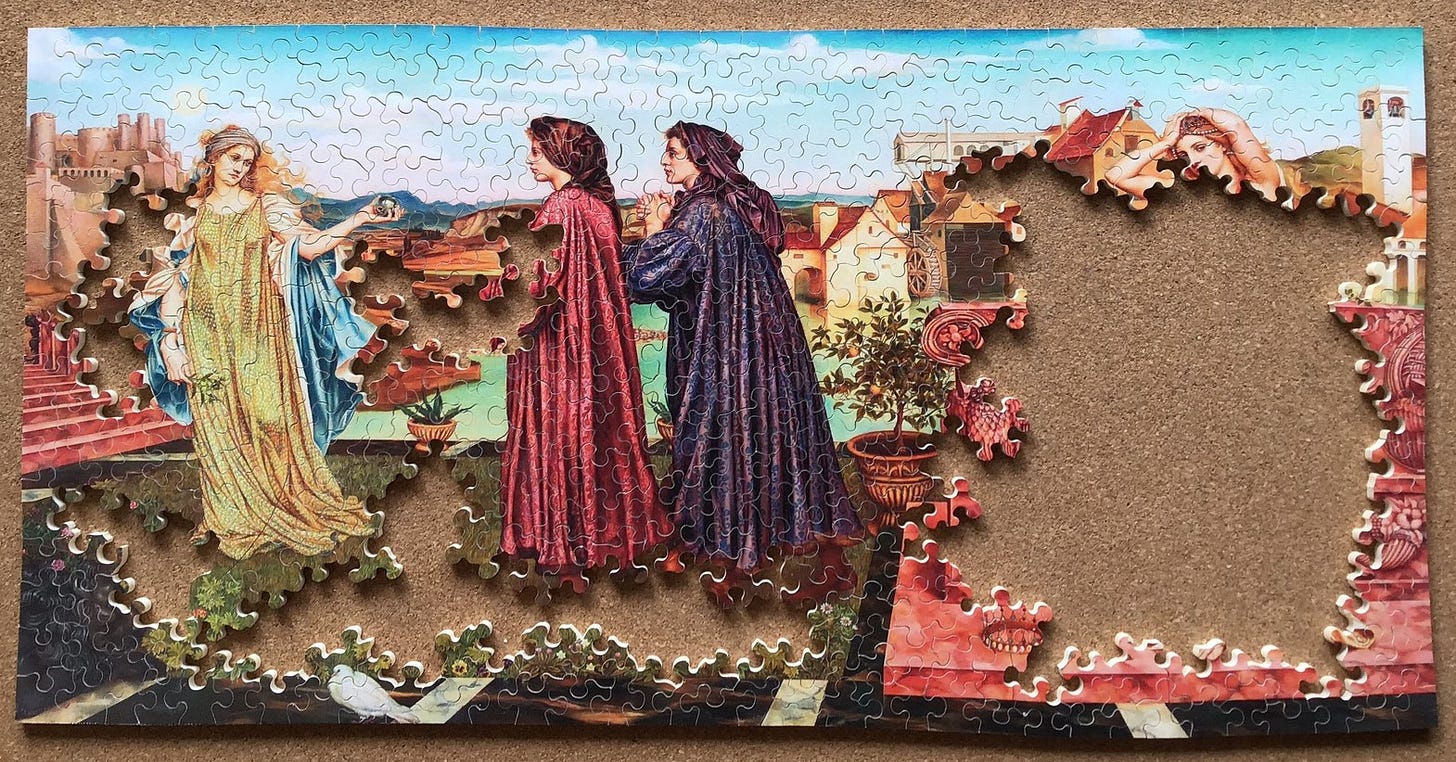

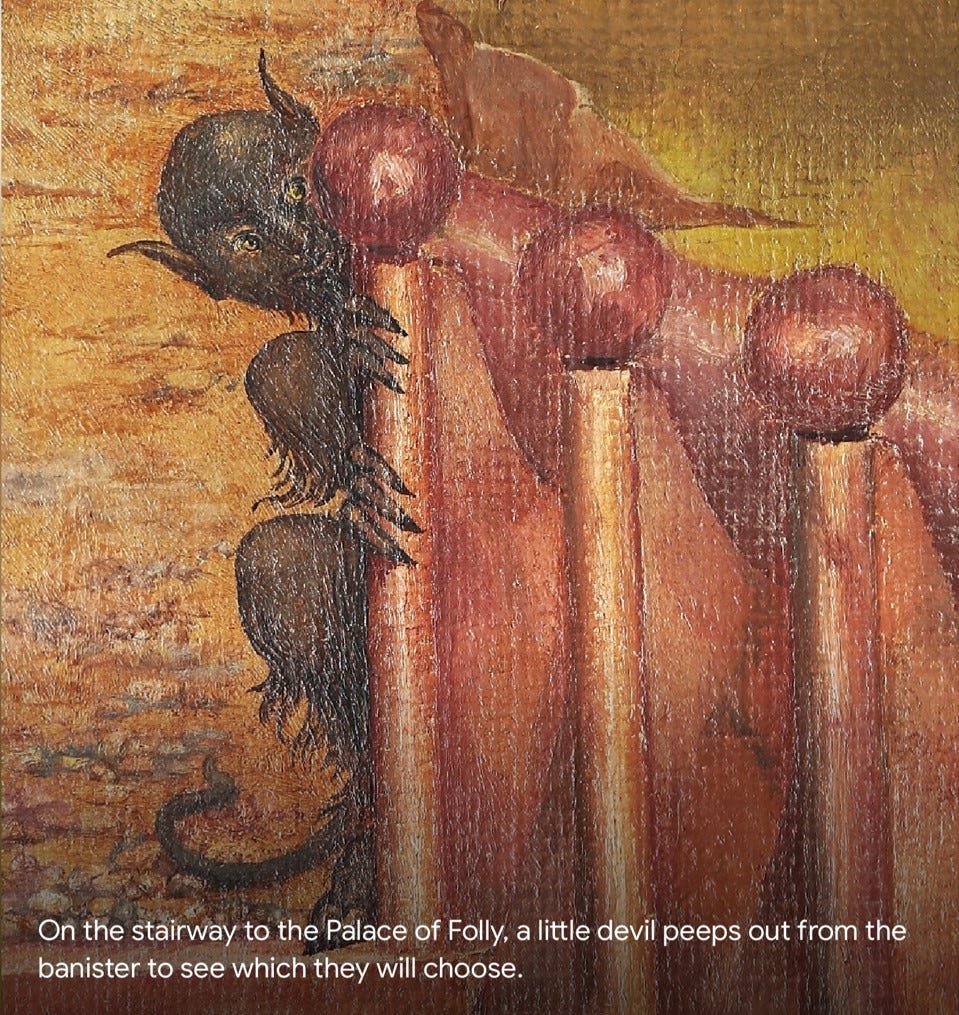

Evelyn De Morgan’s The Garden of Opportunity was painted in 1892. It is a large oil-on-canvas work that is more than a metre tall and nearly two metres wide. The painting tells an allegorical story. It depicts two students who are turning away from Wisdom and are being drawn to Folly. Their faces and body language, and the sad expression on Wisdom’s face, suggest to me that they have already made their decision. I presume that it is meaningful (but I don’t know why) that the medieval-garbed students in this moralistic painting appear to be female twins. (The vast majority of characters in Evelyn De Morgan’s paintings are women.)

I have already gone into way too much depth about Evelyn’s life and legacy for what is after all supposed to be a review of a jigsaw puzzle, so I won’t further discuss the symbolism that is the core of this painting. For that I encourage you to scroll down through this brief analysis from Google Arts and Culture that includes beautiful close-ups of a high resolution photo of the painting.

In general, it seems to me that Pre-Raphaelite painting is the opposite of Impressionism. Evelyn De Morgan did not paint subjects or the effect of light on them – she painted symbolic representations of values and emotions. As you would expect, although Evelyn stayed with the Pre-Raphaelite style throughout her life there was evolution in both her artistic abilities and the themes that she chose to portray in her more than 100 oil paintings. Here is a brief article that includes more samples of her work and discussion of Evelyn’s place in the “brotherhood” of second-generation Pre-Raphaelites.

Assembly

Normally I would put a Spoiler Alert in at this stage but I don’t feel a need to do so for this puzzle. It isn’t in regular production, and even its image isn’t available from any other puzzle-maker except by special order. Sr.B does take custom orders but since all of his cutting is free-form these pictures would not be spoilers.

I learned that this puzzle was available because someone posted an online message with a link to it right after it was put up for sale on the Sr.B Etsy site. With a few rare exceptions, their one-of-a-kind puzzles sell very quickly, often within minutes of being posted. So this is one of the rare cases where I did not study the image carefully before buying. When I first glimpsed it I knew that I liked it and I knew that I had to act fast, so I immediately moved on to placing my order. I was thrilled when the Etsy bot did not say the puzzle was already sold after I got the shipping and payment information filled in. As you can see in the above photo, there is no picture on the box so I had very little memory of the composition of the image when I began the puzzle. All I remembered was that it was a wide landscape Pre-Raphaelite painting.

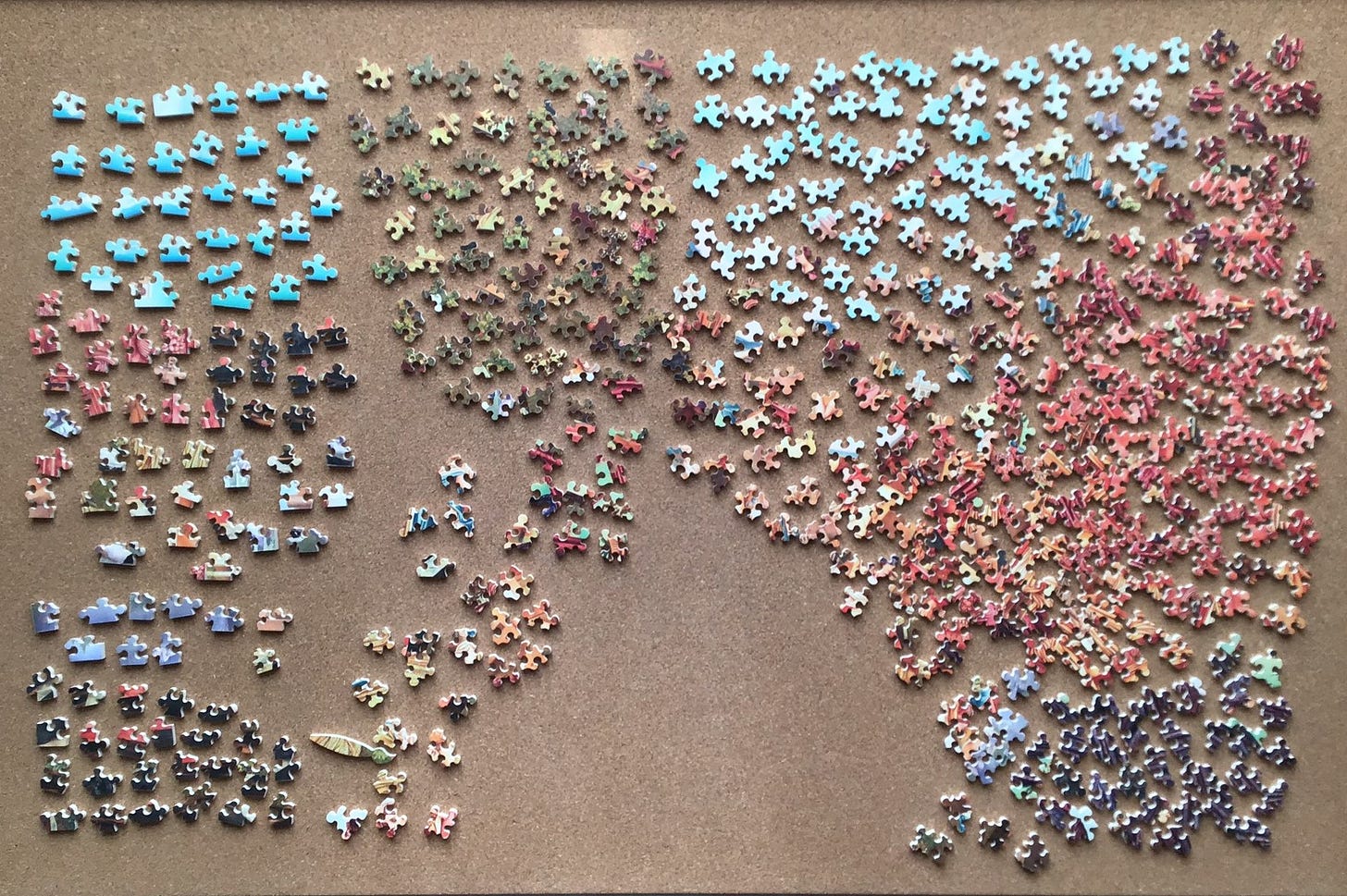

When I removed the pieces from their elegant wood box with crimson felt lining I was immediately struck by the high quality of the printing. The colours, printed on paper, are very vivid as the following photos will show. I was also immediately aware of the beautiful and varied abstract shapes of the pieces. They were fun to sort. There was only modest amount of sky blue and grassy green but there sure seemed to be a lot of red.

At first I resisted the temptation to assemble the puzzle edge-first even though those presumed sky pieces looked awfully tempting. But I did notice that there were a number of apparent edge pieces that had more subdued colours than all of the others and wondered what that was all about. As I began assembling them I remembered that the Sr.B Puzzles Workshop always includes a bonus mini-puzzle of a different fine-art painting. In this case it is Georges Seurat’s pointillist masterpiece Bathers at Asnières.

I continued with colour-matching but made slow progress. I put priority on trying to make assemblies based on the head and hair of the women. The difficulty of the baroque style of cutting, combined with my lack of knowledge about the image, led me to resort to building the edges in order to give my colour-based sub-assemblies some context. Fortunately for me Sr.B does not include disguising of edge pieces in its bag of tricks.

As I expected, the sky proved to be an easy build …

… and that gave me an opportunity to put all four of the women’s heads into place.

That made a big difference. I could now see the image taking shape even though I still did not know anything about the story it was telling. I did do some of my research about Evelyn De Morgan in parallel with assembly, but to avoid inadvertently seeing the image I did not do any research about this particular painting until after assembly was complete. Therefore I did not know that the more beautiful women were Wisdom and Folly, or that the two “twins” were students.

After that, assembly proceeded pretty much as you would expect for a puzzle in which progress depends upon following colour clues. As I had anticipated due to the style of cutting it was indeed quite challenging, but very satisfying and enjoyable.

Wow! An impressive essay and presentation today, Bill. It was quite different in focus than your other postings, and seemed to be quite a novel departure from your usual practice of making the puzzles the main focus. I wouldn’t suggest that you give us this sort of “change of pace” every single time, but it sure was a nice experience today.

I particularly enjoyed your “descent down a research rabbit-hole” re: the adventures of Evelyn, William, and Wilhelmina. Your discussion of the makers of the Sr.B puzzle was interesting, too. The analysis of the painting used for today’s featured puzzle was brief, but you gave enough links that I’d be able to seek more information about it.

Good on you, too, for sharing your joy as you assembled today’s puzzle. I got quite a kick out of reading about the bonus mini-puzzle of a Seurat masterpiece and about the trick of being able to lift a puzzle and suspend it lengthwise without its coming apart.

Cheers, and thanks for your work.

—Greg Skala