49. Wentworth binge Part 3: The Kitchen at Elmswell Hall, York

This puzzle's image was painted by early Victorian artist Mary Ellen Best. My essay tells her story and includes a gallery of her paintings. (about 3100 words; 35 pictures)

[Reminder: Most of these pictures are fairly high resolution. You can zoom in to see the details.]

Wentworth Wooden Puzzles (shiny green box with flags; plain green bag)

no Wentworth stock number on box

artist – Mary Ellen Best (1809-1891) painted 1834

242 pcs 9¾” x 14” (25 x 35.5 cm) ave. 3.7 cm²/pc 3½ mm mdf

This is probably my favourite Wentworth puzzle to date, partly because it has an enjoyable cutting design that includes tricks that their puzzles usually lack, but more importantly because I have really come to appreciate its image which is undoubtedly a true-to-live glimpse into the kitchen of an early Victorian-age upper middle-class home. It was painted in 1834 by English artist Mary Ellen Best. I had a lot of fun doing the research that this puzzle inspired, and collecting photos of the other paintings that accompany this essay.

Mary Ellen Best was roughly contemporary with William Powell Frith who painted The Railway Station profiled in last week’s newsletter, born ten years earlier than him. They both came from Yorkshire, but because of their genders their respective artistic careers were very different.

During early Victorian times drawing and watercolour painting in the classical style was not only acceptable for women, it was encouraged as a suitable form of recreation hobby for British ladies. The Queen herself was rather proud of her drawings and watercolours and would show them off for visitors.

On mainland Europe at the time, women were beginning to become accepted as professional (or more accurately, semi-professional) artists. But in England they were expected to do it only for their own recreation and amusement, and as a way to demonstrate their artistic sensibilities for potential suitors. And only watercolour painting was acceptable for women in England in at that time: It was considered very unladylike for a woman to enter into the smelly masculine realm of oil painting.

Ellen, for that was the name she went by, came from a prosperous middle-class York family. Her father was a doctor, and her mother was the daughter of a prominent Yorkshire landowner. Ellen’s father died when she was only 8 years old but her mother received sufficient funds from his estate, as well as a substantial inheritance three years later when her father died, so the family was able to live a comfortable life.

After early tutoring at home, both Ellen and her older sister Rosamund were enrolled in Mrs. Haugh’s boarding school in Doncaster. Mrs. Hough’s students learned to speak French, and I assume that besides reading, writing and basic arithmetic they also received instruction in embroidery, music, dance, etiquette and the social graces; all of the things that a proper young middle class Victorian lady needed to learn in order to “marry well.” One of the teachers there took an enlightened approach to the teaching of geography, which might have inspired Ellen’s later love of travel.

There the Best sisters also received lessons in drawing and watercolour painting from Mrs Haugh’s husband, the Royal Academy trained professional artist George Haugh who was a frequent exhibitor at both the Royal Academy and the British Institution. By the time she was 12 years old Ellen could paint credible watercolour portraits.

In 1824, when Ellen was 15, their mother enrolled both sisters in a different boarding school, further afield south of London. Miss Shepherd’s School, in Bromley Common, had recently been established by Fanny Shepherd. She took a different approach to girls’ education modeled after the teachings of the Swiss educational reformer Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi.

Fanny Shepherd believed that girls should develop and strengthen their natural abilities and be able to be as self-sufficient as possible. At the time those progressive ideas about education were quite unusual and modern even though in fact they were derived from the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s educational plan for Sophie in his 1762 polemic/novel Émile. That approach probably reflected the girls’ mother’s own approach to raising her daughters as well as their own inclinations.

I get the impression that developing skills with the intention of “marrying well” were not central features of Miss Shepherd’s school’s curriculum although they undoubtedly continued to receive tutoring in the arts of their choice from now-unknown teachers. (Somewhere along the line Rosamund became quite proficient at engraving.) Fanny became a life-long friend for both of the Best sisters.

After Ellen completed her formal schooling in 1828 she returned to live with her mother (since she did not marry until the uncommonly advanced age of 31.) According to this online biography by historian Dinah Tyszka:

Ellen had regarded herself as a semi-professional artist from the time she left Miss Shepherd’s school, but knew that she still had a lot to learn including the mastery of perspective which she found very difficult. Unlike her male contemporaries she could not study at the Academy School, and the first art school [in England] to admit women, in Bloomsbury, did not open until 1835.

[Initially] Ellen’s paintings were primarily portraits, often commissioned by her family and friends and by people in the wider area around York. A large proportion of these were of women. She also painted still life subjects and, in May 1830, won an award ‘for the best original composition, painted in oil or watercolours … by persons under the age of twenty-one.’ Gradually, she extended her subject matter from still life into capturing buildings and their interiors and introduced people into the compositions, thus recording the costume of the time.

Ellen loved travelling. Besides excursions in England and Wales, she began touring Netherlands and Germany. At first she did it with her mother, and later with her maid and companion Elizabeth Alderson as chaperone. She painted interesting scenes she saw, the way that people now take tourist photos. As always, her artistic style was that of a realist, aiming to show things accurately as she saw them, without romanticism or flattery.

She obviously had an impeccable eye for details, especially in women’s clothing, hats and hairstyles:

She did the same for the furniture, paintings and knick-knacks in the rooms that she depicted, portraying exactly what she saw. For that reason her paintings are now considered to be a valuable resource for historic research into the times and places she depicted.

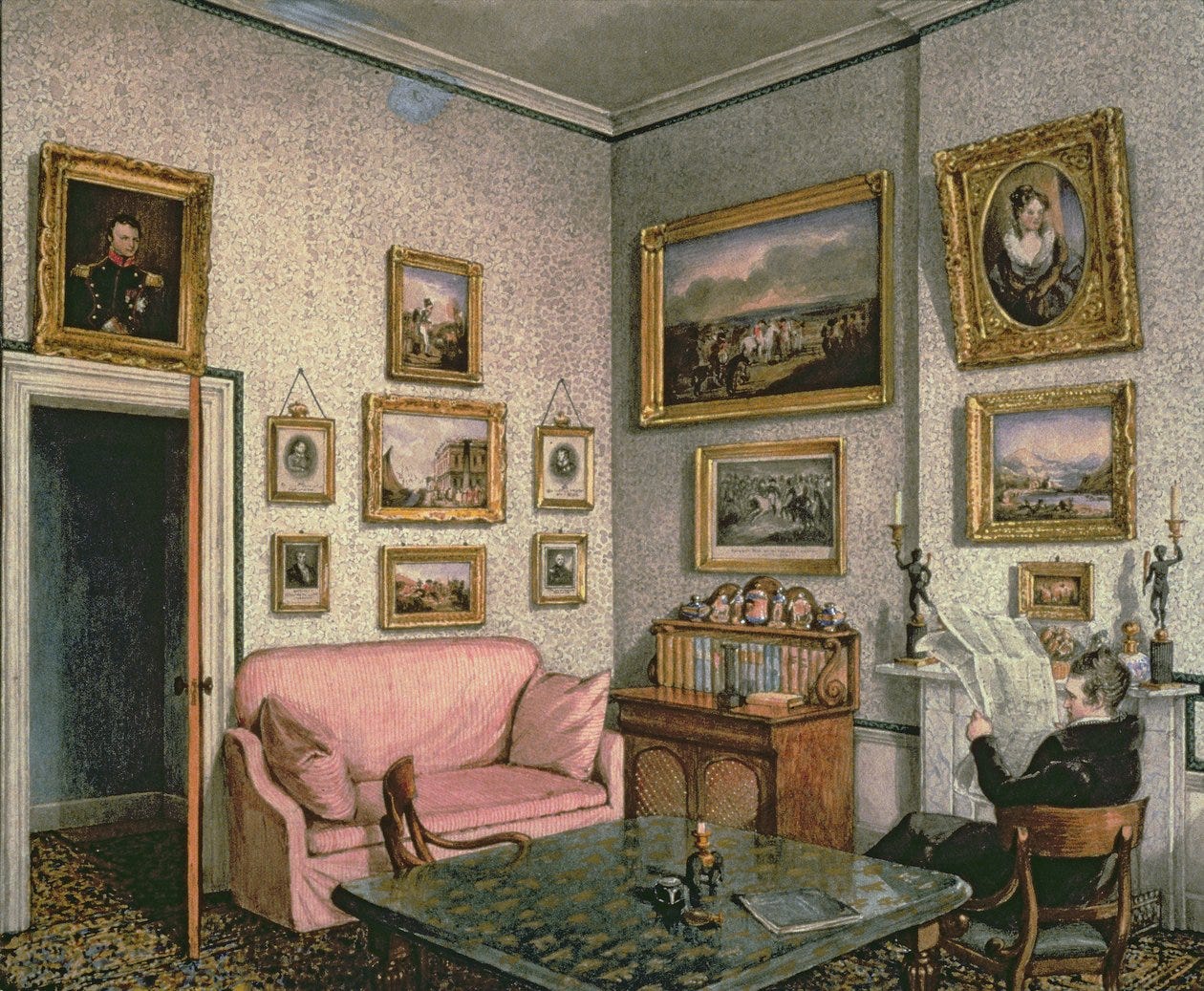

As with this puzzle’s image, many of her paintings were of rooms, with or without an inhabitant. Some of those, like The Artist at Work shown at the beginning of this write-up and of the other rooms in her house in York, were clearly meant to be personal keepsakes. Others may have been painted to be a “hostess gift” for the ladies that she was visiting, or done as commissions.

Interior decorating was one of the most common expressions of creativity for a middle-class woman of her time, but it produced a very transitory accomplishment: To the extent that they could afford it, rooms where they entertained visitors would have been frequently updated to reflect changing interior decoration fashions.

The next painting is a self-portrait painted by Ellen in 1838, after her mother had died and she had inherited her leased semi-detached house. As I studied it I realized that it might be a remodeled version of the same room as the previous painting of the drawing room. It makes sense to me that Ellen would have chosen whichever room received the most sunlight to be her painting room, and that she would have given a priority to remodeling such a room to suit her own personal aesthetic tastes.

The street address system in York has changed since her time but this is believed to have been Mary Ellen Best’s semi-detached house:

Ellen painted the following three paintings at her grandmother’s home – Langton Hall, the manor house 17 miles from York where her mother had grown up and which was later inherited by her elder Rosamund. I expect that it was a relatively familiar place for them to visit. (Langton Hall is now operated as a B&B and spa.)

Paintings of everyday life in the kitchens of the manors or hotels where she was staying seems to have held a particular interest for her. This type of subject matter for a painting was uncommon then as it still is today.

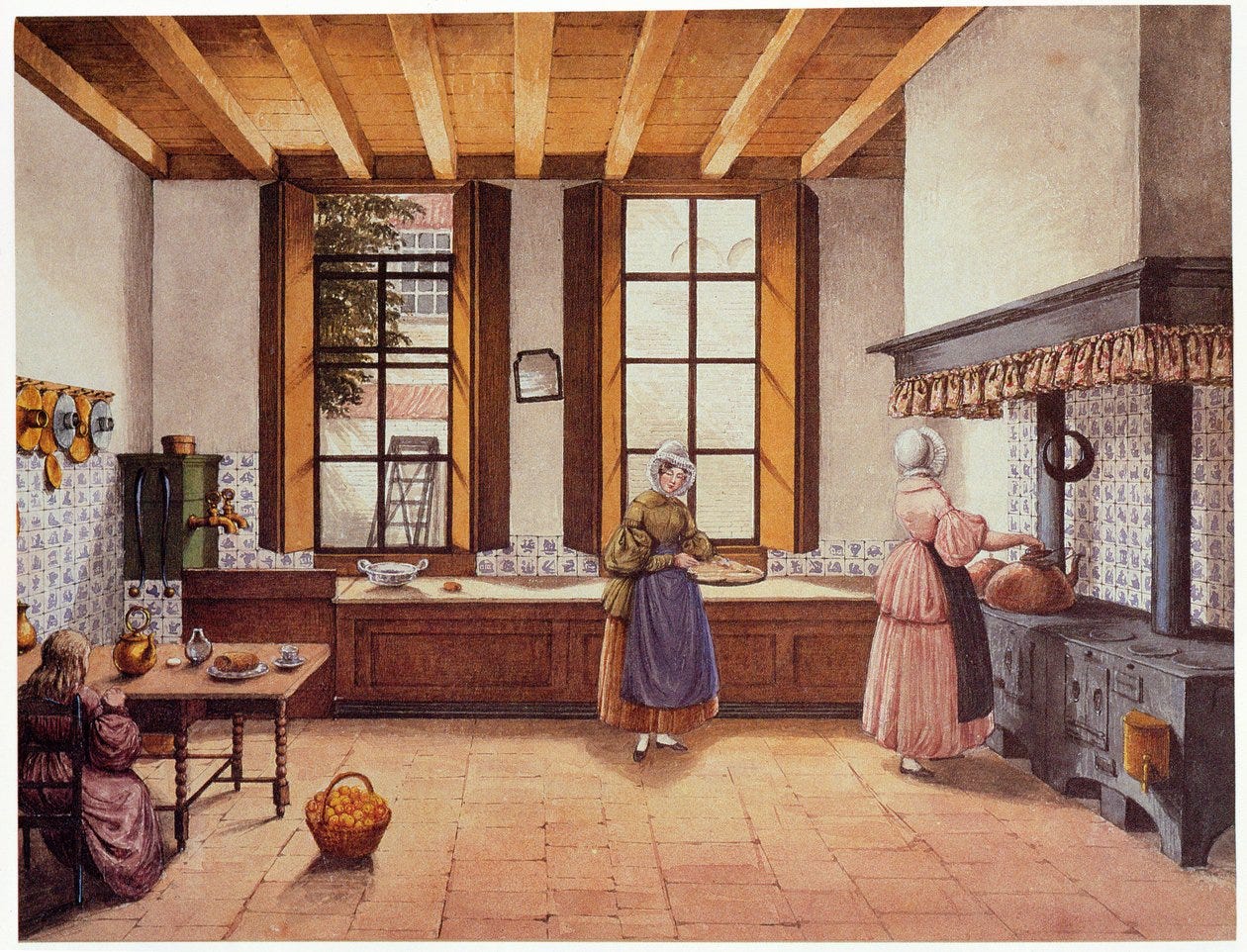

And that brings us to the image of this puzzle which was painted in 1834 and is held by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It is entitled The Kitchen at Elmswell Hall, York, which was her father’s family’s ancestral manor house in East Yorkshire. This Elmswell Hall (there is another one in Suffolk) is in East Yorkshire about 175 miles from York. In Mary Ellen Best’s time travelling to visit her deceased father’s family would have entailed several days of uncomfortable carriage travel on rough roads so I suspect tht going there would have been a rare occasion.

The Elmswell estate dates back to the time of William the Conqueror, but the manor house in the painting was built by Henry Best in 1634. About him, according to this source:

Although he may be classified as a member of the ‘middling’ gentry … he was a ‘muddy booted’ working gentleman farmer. The [estate] of Elmswell amounted to just under 1300 acres, plus the rights of pasture for 360 sheep in a neighbouring area of 500 acres. Of the 1300 acres, Best farmed approximately half himself and rented out the remainder to tenant farmers.

Henry Best sought to apply scientific principles to farming and published two books on that subject. They provide a valuable insight into his methods and remain in publication by the Oxford University Press to this day. The manor building is now a ruin, but despite that it is a Grade II* listed historical building; the asterisk indicates that it is "of more than special interest" according to English Heritage. Only about 6% of England’s Grade II buildings have this special status.

Assembly of a 250 piece Wentworths is pretty straightforward and when I first assembled The Kitchen at Elmswell Hall last July I did not document it except for a final photo of the completed puzzle. I didn’t expect to do a write-up about it: After all, what is there to say about an old kitchen? But the completed puzzle hung around on one of my side-boards for quite a while. I didn’t want to pack it up and put it away since I was enjoying looking at it, especially after I began doing research about Mary Ellen Best.

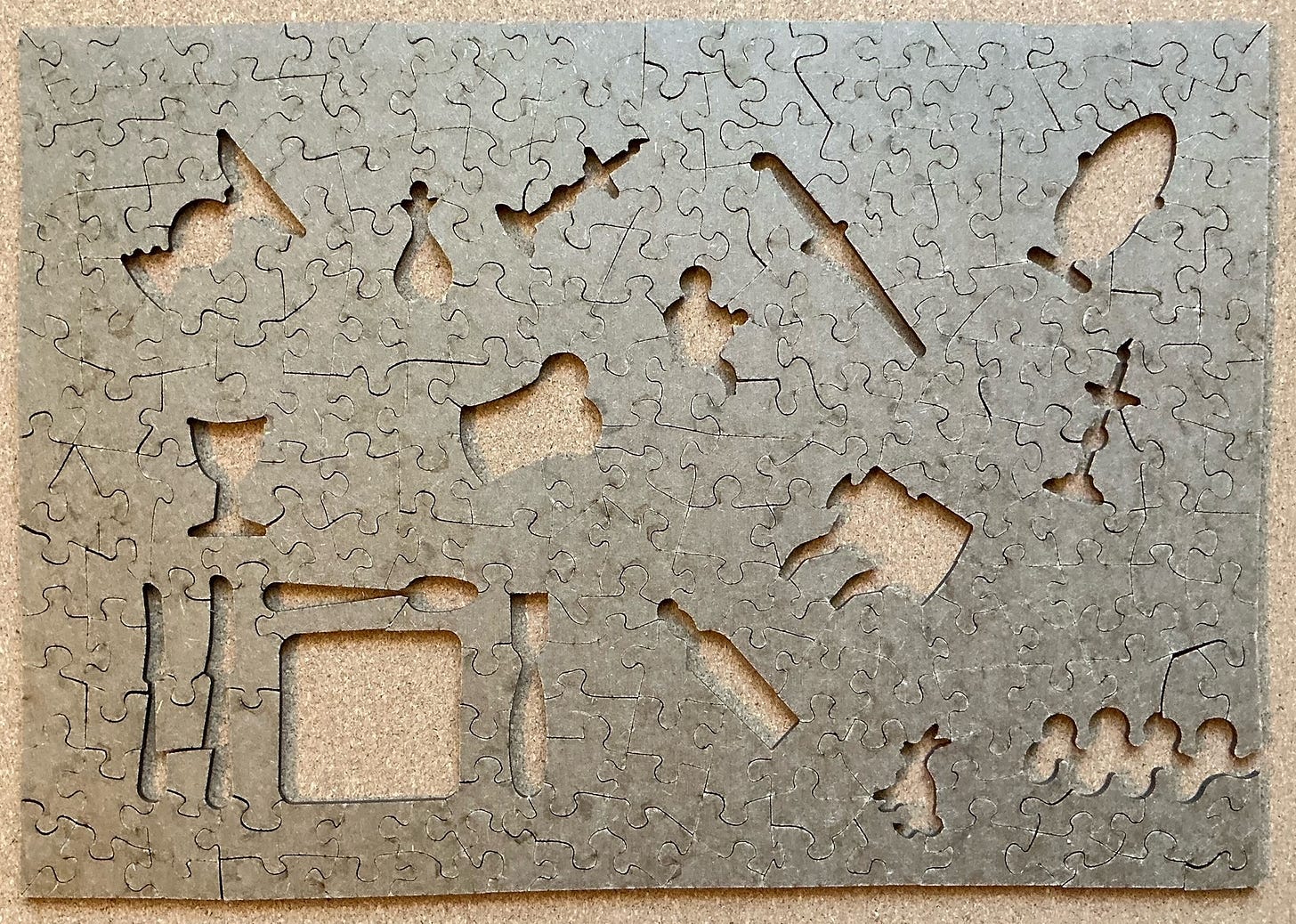

And after I did disassemble it and loaned it out to others my mind kept coming back to it. So when I did these other two Wentworth building interior puzzles I decided I wanted to include it in this series. That entailed re-assembling the puzzle to take the following in-progress photos. Since its image was still relatively strong in my memory, as with The Yellow Room I decided to add the extra challenge of saving the figure pieces for the end.

I began with the light-coloured pieces with the window, and some other colour targets of opportunity. That gave me the face of the maid or cook so I immediately had the painting’s centre of attention:

The blue & white porcelain and other pottery gave me more targets of opportunity, and sometimes I could link my assembly islands together:

In this case, due to the nature of the image and its somewhat more difficult cutting design, not putting in the whimsies (and not looking at them for hints) was adding much more challenge that it had done for assembling The Yellow Room.

I turned my attention to the light-coloured pieces with horizontal stripes …

… and the floor with its patterned rug. As usual now that there were fewer pieces, assembly quickened:

In this image I particularly enjoyed seeing the fine chairs that had been relegated to the kitchen, presumably because the dining room had been remodeled to keep up with changing interior decorating fashion. I still can’t tell what the woman in the painting is doing with that white stuff in the trough. Is she making bread? Or doing laundry? (There is laundry drying on a clotheslines on the left side of the picture.) There does not appear to be a stove in this kitchen; perhaps Ellen positioned herself in front of it to paint the picture.

I cannot imagine that Mary Ellen Best ever thought of this as being a saleable painting, although she painted it during the peak of her short career as a professional artist.

Actually in fact, as far as I know there is no clear indication that Ellen ever actively tried to market herself as a professional artist. She did submit paintings (as i understand it, always as not-for-sale) to juried exhibitions at various cities around England, and later, in Holland and Germany, but perhaps that was more for the gratification of having them get accepted.

She never established a professional studio, but she did sell some paintings to London art dealers via her framer in York, but that apparently was a very minor part of her professional output. Mostly, I imagine that she would show her keepsake paintings to friends and acquaintances, and that led to requests from them that she take on a commissioned painting. As mentioned above, she really didn’t have a need for the money since she was financially quite well off.

In any event, her time as a professional artist was short-lived. Her selling of paintings began and rose quickly beginning in the very late 1820s, tapered off fairly rapidly from about 1935 to ‘37, and stopped completely when she married in 1840. It is not likely that it was demand for her paintings that diminished: It seems more probable that the inheritances from her father and grandfather, and then when her mother died in 1837, were a factor. She was sufficiently wealthy that she could choose to apply her artistic talents to painting things that she wanted to paint, rather than what other people wanted from her. Perhaps she felt that she had proven herself artistically. Or perhaps she just got better at saying “no” when people asked her to do a commission.

When she married a German schoolteacher named Francis Charles Anton Sarg in 1840 he too was able to quit his job and devote his time to family life and being an amateur musician. Ellen continued to paint occasionally in her spare time in the 1840s. But what with the demands of being the mother of three small children (since she apparently chose to raise her three children herself rather than hire a nanny, which would have been very unusual for a wealthy woman of that time) her painting became less frequent and their subjects generally became more family-oriented. Then her artistic output almost completely stopped by the early 1850s when she was about 40 years old. Her last known painting was a now-lost still life vase of roses painted in 1860.

Over the years, the children grew up, and Frank and Fred moved to Guatemala where they founded an export business specializing in coffee. Frank was appointed as the German consul there. Ellen’s artistic genes re-emerged in Frank’s son Tony, who moved to the New York and became a successful puppeteer, animator, toymaker and illustrator. He was the person who invented and designed the first giant balloons (upside-down marionettes) for the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parades. It is pretty off-topic for this essay but I recommend that you check out this 16 minute video about him.)

Ellen’s love of travelling had dissipated with age and she never did sail across the sea to visit her sons in the New World. Her husband passed away in 1883 and she died in 1891.

Mary Ellen Best had been a very prolific artist for a short while, but her subject matter and style went out-of-fashion in the art world. Late in her life she had organized her paintings into albums that had been left to her offspring but they languished in attics. Before long she was largely forgotten even by her descendants.

In the early 1980s one of those descendants brought 47 of her paintings to the famous Sotheby’s Auction House but was told that they were unsaleable. Fortunately, a Sotheby’s colleague saw them and suggested that they could be promoted as a diary of early 19th century daily life. That worked: The paintings were mostly bought by museums rather than by art collectors.

A year later another descendent, totally unaware of the sale of that first batch, brought in another of Ellen’s albums. That led social historian and journalist Caroline Davidson (who had previously written a book called A Woman's Work Is Never Done: A History of Housework in the British Isles 1650-1950) to conduct research into Best’s life. That included discovering a treasure trove of information in the extensive journals that had been written by her sister Rosamund. Davidson’s biography, The World of Mary Ellen Best, was published in 1985 and most of the information that I found online originates from that source.

Mary Ellen Best painted an estimated 1500 watercolours while she was active, of which fewer than 400 are known still to exist. But she has opened up a whole new market for domestic genre paintings that are now considered to be desirable, and has emerged as an artist worth collecting. Most of the paintings that have surfaced to date have come from descendants. Perhaps there are many more such paintings and sketches by her and other early women artists waiting to be discovered (and perhaps, have their images turned into jigsaw puzzles.)

Coming up:

This Wentworth binge continues with the first of two puzzles that have images of the launching of lifeboats to rescue shipwrecked sailors.

Interesting research and commentary today, Bill!

The fact that the Queen herself was interested in drawing and painting watercolours may indeed have made it easier for some Victorian-era women painters to be acknowledged. Mary Ellen Best certainly seems to have been a good one.

The image used in the first puzzle included in your posting really intrigues me. I don't doubt that it depicts a kitchen, yet the look of that kitchen is so surprising. For one thing, the floor pattern is elaborate. For another, the chairs and plates seem extra fancy. Still, there are a variety of functional kitchen items here and there. I'd like to see more evidence of how water was supplied to this Victorian kitchen.

Fanny Shepherd's school seems interesting, as does the lasting influence of Johann Pestalozzi on education. I looked him up, thanks to the link you provided.

Though I'm not the expert on wooden puzzles that you are, Bill, I must say that these Wentworth puzzles seem to have a lot of "positives" going for them. No wonder you particularly enjoy many.

Of the additional paintings included in today's posting, my favourites are "Exhibition of the Works of Modern Artists in the Ball-room of the Goldnes Ross Hotel, Frankfurt" and "Market Day, Dusseldorf."

Thanks,

Greg