11. Artifact Puzzle: Woman with a Parasol, by Claude Monet

A review of the puzzle that uses this relatively early impressionist painting as its image, the story behind the painting, and a walkthrough of my puzzle assembly (about 3600 words; 28 photos)

Artifact Puzzles Fremont, CA released July 2016

artist – Claude Monet puzzle designer – Tara Flannery

laser-cut ¼” (6mm) 3 ply

357 pieces 13¾” x 10¾” (35x27 cm) average piece size – 2.65 sq cm (0.41 sq. in. )

After having assembled three relatively small puzzles in a row I felt ready for something more challenging. But it still feels like summertime, and for some reason I think that calls for some restraint in difficulty, so I chose this medium-size one (357 pieces) with an image that I knew would not be nearly as generous with colour-clues as my recent Miss Masque one had been (although I hoped it would include brushwork clues that the comic book cover had lacked.)

I am re-organizing my order of presentation again. This time I will continue to put the puzzle review at the beginning but I will move the whole assembly section to below the Spoiler Warning. As will be explained below, that is because the in-process pictures would give you more information about the puzzle’s cutting design than you may want if you decide to buy the puzzle based on this review.

My puzzle review

This is the first puzzle that I have assembled made by Artifact Puzzles, who have a reputation for entertaining cutting designs. The California company was founded in 2009 and has a very large selection of both styles of art and cutting. They are one of the few large puzzle makers that features the name of the cutting designer in the puzzle description in its online catalog. After completing the puzzle I looked it up for this review. This one is by Tara Flannery and the catalogue describes it as having an “ornamental” cutting design and being of “harder than average” difficulty. Perhaps it is a spoiler for the rest of my review but I would say that is a fair description.

[Digression: Artifact does a few other things that are different from other wooden puzzle companies. As far as I know, it is the only one that makes puzzles in two separate locations; its original workshop in Fremont, CA and a workshop located in Port Townsend, Washington. It also has two lines of puzzles: its regular line, that is printed on shiny paper and has rather prominent cut-lines, and an Ecru line that is specially laser-cut with a narrower swath and has matte rather than glossy printing. Its Ecru puzzles cost more on a per-piece basis than other Artifact puzzles.

Artifact also has spun off a separate entity called the Hoeffnagel Wooden Jigsaw Puzzles Club. It is a revival of the puzzle library format that thrived in the 1930s in which people can rent rather than buy puzzles. Members pay a fixed fee for six months or a year, and the mailing costs to ship puzzles to the next member in its queue. They have puzzles from various makers, not just Artifact and Ecru, and you are entitled to as many puzzles as you can assemble during your membership tenure. You can read more about it here. There are many ravenous puzzle-people in the Facebook Wooden Puzzle Club that subscribe to this service who are very pleased about the cost savings it gives them. Unfortunately for me, because of postage costs only Americans can participate.]

The current price for this straight-sided 357 piece puzzle from the company is $90 USD which is in the same general range as other premium brands of 1/4” laser-cut puzzles such as Liberty, Nautilus, FoxSmartBox, Stumpcraft and Puzzle Lab. Therefore my assessment standards will be those that apply to higher-priced premium laser-cut puzzles.

Artifact Puzzles of about 250 pieces or larger are packaged in a well-made pine box – the sides and top are over 8mm thick! Smaller puzzles are in sturdy, attractive blue magnetic-closure boxes. In both cases the packaging makes a good impression, demonstrating that its contents really are intended to be a precious family heirloom. My only complaint is that I would prefer to be given the option of less extravagant package so that I could afford to buy their puzzles more frequently.

The pieces are ¼” inch thick (6mm) 3ply with two thin hardwood veneer layers enclosing a thick inner layer. The bright images are printed with soy-based ink on paper that is securely heat-sealed onto the puzzle. This has become the most common practice for wood jigsaw puzzles these days. (Vintage puzzles sometimes had problems with the paper peeling away from the pieces. That problem is very rare now.)

Personally, I prefer the 3D visual effect that often comes from using a UV printer to print the image directly onto the wood. But I think of that technology as giving extra bonus points rather than that its absence is a shortcoming for a premium puzzle. The paper in this puzzle is glossy, rather than matte. Glossy paper gives a brighter image but I think that this particular painting would have been better suited for the matte finish which Artifact uses in its more expensive Ecru line of puzzles

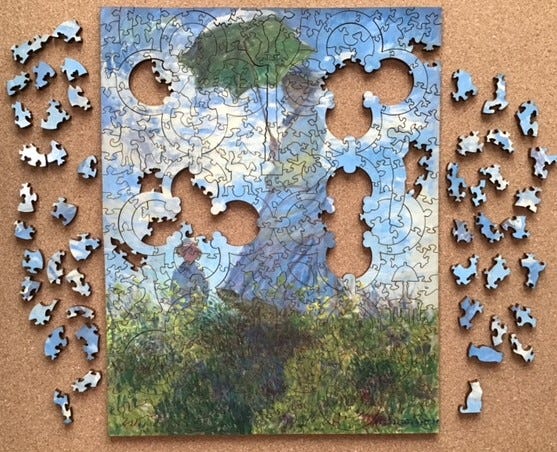

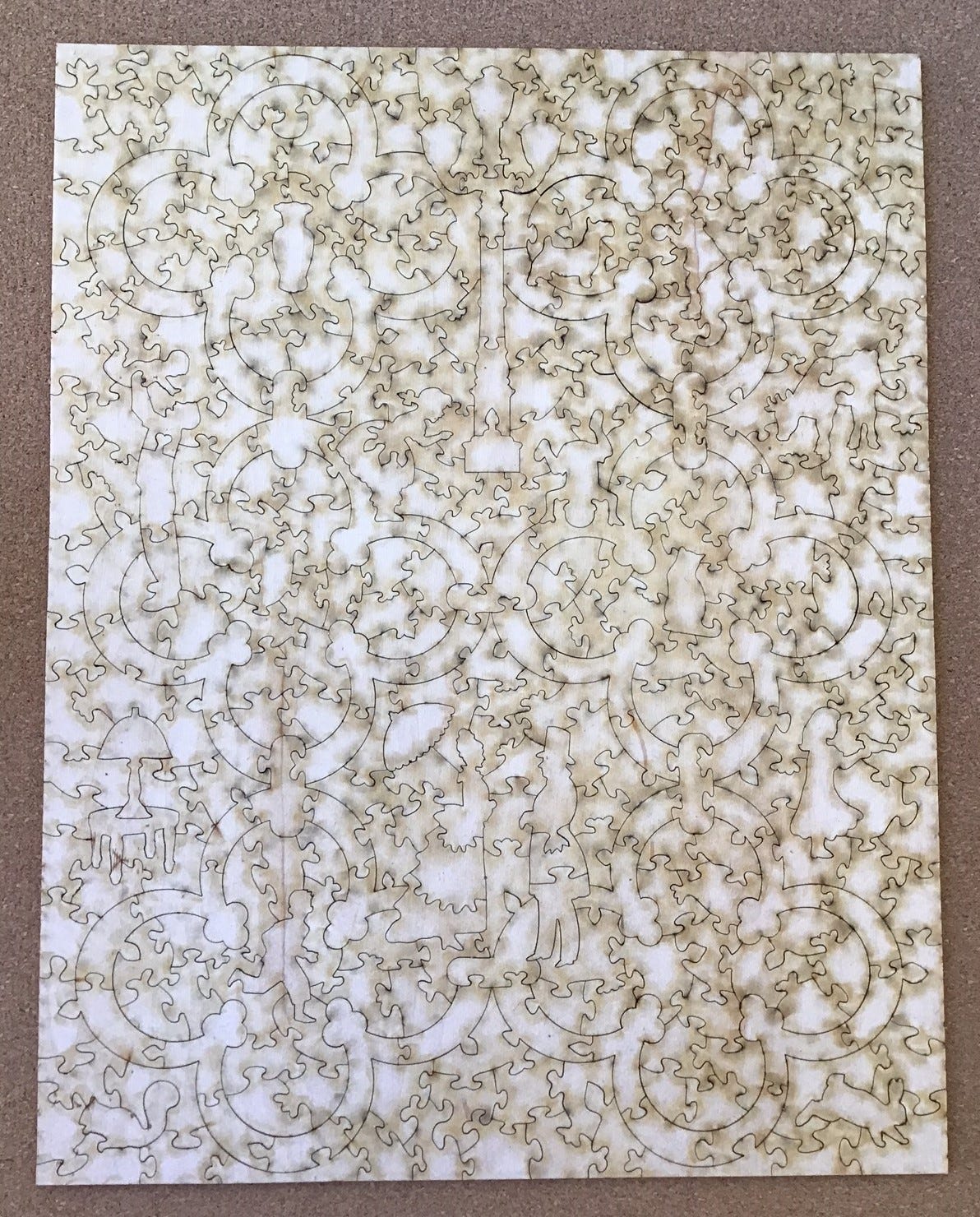

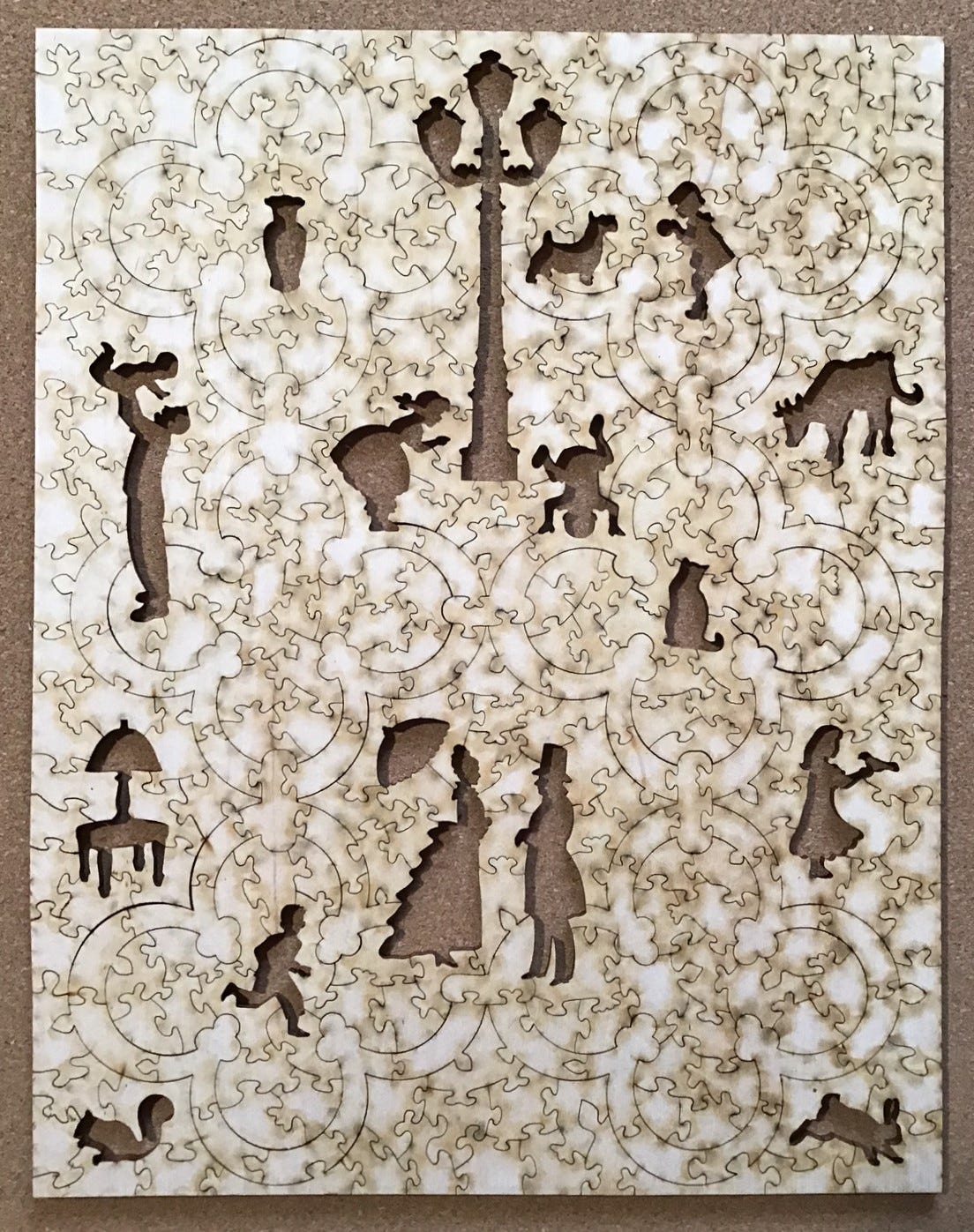

Pouring out the pieces one characteristic jumped out at me – most of them have one or two sides that are a semicircle, as shown in the opening photo for this posting. Here is photo of the sorted pieces:

The two large blue and green groups on the left are pieces that have semicircular sides. This photo understates the number of pieces with a semicircular side because after I took it I kept finding many other pieces that I had missed and had to add them to those groupings. There were also 24(!) pieces that had two curving arcs formed by semicircles that converge into a trefoil shape:

Figuring out what puzzle designer Tara Flannery is up to with this geometry is what this puzzle is all about. That is why I have moved the puzzle assembly section of this review/essay to below the Spoiler Alert. All I can tell you about the general cutting design now is that the puzzle’s assembly was both fun and challenging, but not frustrating. In other words, exactly what one wants in a jigsaw puzzle.

The puzzle’s 9 single- and 7 multi-piece whimsies (AKA figural pieces or silhouettes) are attractive and relate to the time-period in the Monet painting. The above photo shows how they sometimes are placed to interact with each other. In fact, these aren’t even my favourite whimsies. There are some of Victorian-era children playing that are delightful. One has the profile of a little girl bent down but holding up a ball, and facing her is a scotch terrier that looks very excited.

Of special note is the fact that they are all very life-like as true silhouettes - none has accent lines in order to make the figure recognizable.

I know from pictures posted in our Facebook wooden puzzle group that extensive scorching on the backside of the puzzle is very common feature with Artifact puzzles but I can’t recall anyone ever saying that there was discoloursation on the image side. There was no scorching on the front of my puzzle. Backside scorching is common even among premium puzzles and isn’t considered a significant shortcoming, although frontside discolourization would be.

In our Facebook group the Artifact Puzzles company has many fans. Now I can see why. This is a very fine puzzle!

The artist and image

[Note: To prevent accidently seeing the painting, the research for this background information was mostly done after I had completed the puzzle.]

Claude Monet (1840-1926) was one of the few French impressionist painters who achieved wealth and acclaim in his lifetime, but that was primarily because he had the longest life, most prolific output, and ultimately the most financially rewarding career of any of them.

Most of the original impressionists lived and died in poverty, but at the end of his life Monet was considered by most French people to be an artistic hero. At Monet’s request he was given a simple funeral with only 50 close friends and family in attendance, rather than the large state funeral that the people of France thought he deserved. At the funeral, his close personal friend the war hero and former Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau tore off the black cloth that draped the coffin, crying, “No! No black for Monet! Black is not a colour!” and he replaced it with a bright flower-patterned cloth.

But Monet’s fame and fortune (as well as his beloved gardens at Giverny, his failing eyesight, and 10 year obsession with his huge Water Lilies war memorial) were still a long way front of him when he painted this image in 1875. At that time he was still a young artist painting in a not-yet-popular new style, struggling to support his wife Camille and young son Jean, the two people that you see in this painting.

The previous year, Monet along with fellow aspiring artists who were tired of having what they considered to be their best paintings rejected for the stuffy Académie des Beaux-Arts’ annual Salon exhibition, had self-financed their own exhibition. It was held in a large, bright, vacant third-floor photographer’s studio they rented on Paris’ still-new but prestigious Boulevard des Capucines.

Most of the relatively few people who came to the month-long exhibition came to laugh and gawk. Financially, the show was quite disappointing because it’s one-franc entry fee did not cover its costs, and it resulted in very few sales for the artists. It did however get them some attention, though mostly in the form of mocking unfavourable reviews.

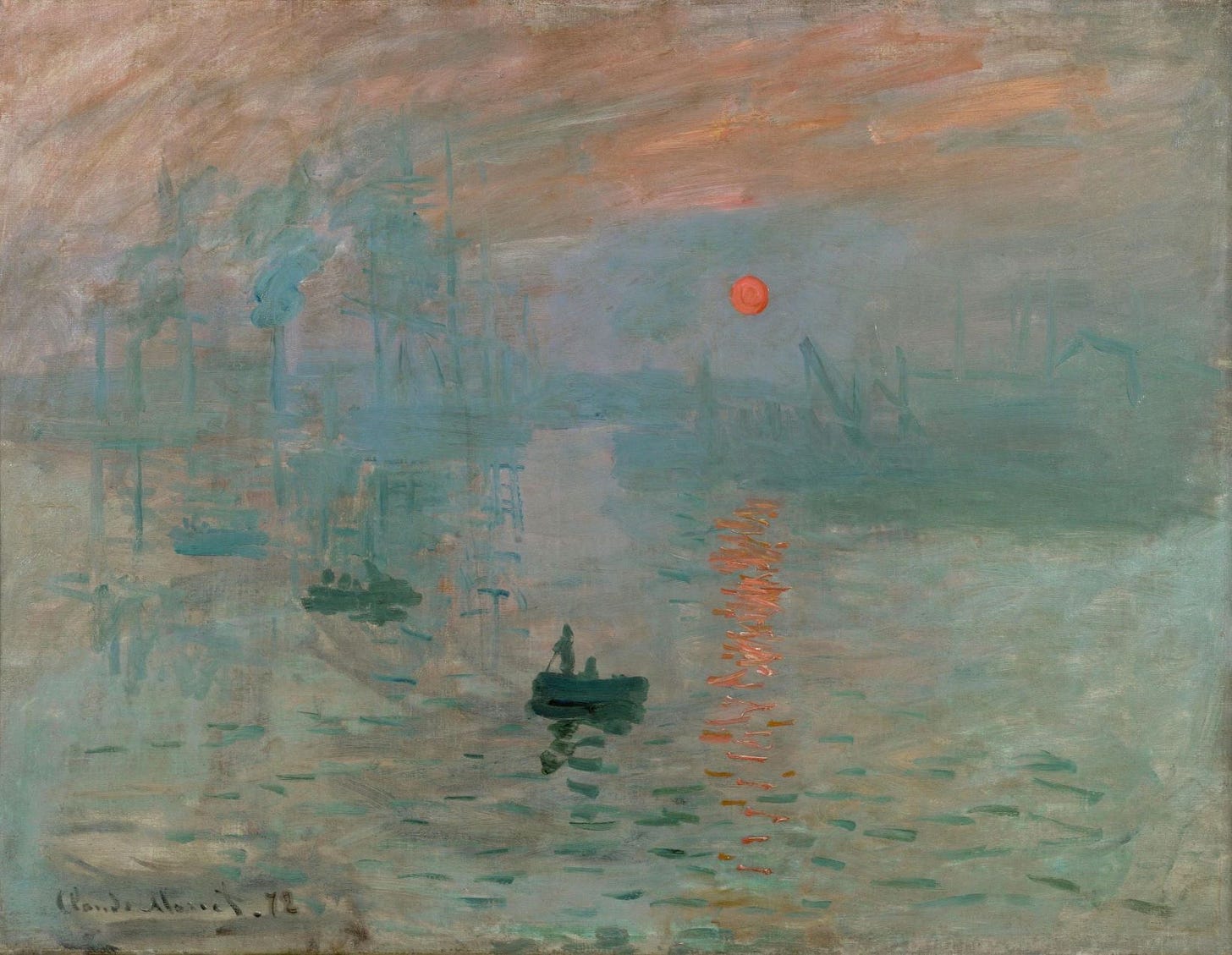

One of those reviews referenced the name of a particularly un-Salon-like painting by Monet called Impression-Sunrise and the reviewer lumped all of the paintings together as being unfinished works: “Impression! Of course. There must be an impression somewhere in it. What freedom … what flexibility of style! Wallpaper in its early stages is much more finished than that.”

Instead of taking offence, the artists adopted the term “impressionists” as a name for their artistic movement which favoured depiction of the fleeting interplay of light on subjects from everyday life over the polished mannerism and classical subjects that the Salon jury favoured. They took pride in the fact that their paintings showed spontaneity rather than meticulous attention to detail.

Six years earlier, in 1865, Monet had met and fallen in love with Camille Doncieux, who was a teenage model seven years younger than him, when he was a poverty-stricken artist couch-surfing in Paris. She got pregnant the following year. At first, he could not afford to marry her or even contribute to the support of the baby he had fathered. But he did marry her two years later when he had his first respite from homelessness and a hand-to-mouth impoverished existence as an avante guarde artist, and they finally began to live together

In 1873, even though sales of his paintings were still few-and-far-between, Monet had a Paris gallery-owner who was willing to display his paintings and he made a few windfall sales. He leased a small house in Argenteuil, a small town on the Seine River about 50 miles from Paris which was becoming an industrial hub. With a six year lease, and considerable optimism that future sales would enable him to continue to pay the rent, Monet planted his first garden there. He also bought a small wooden boat that he converted to a studio so he could paint scenes from the river, and the couple tried to maintain a precarious lower-middle class lifestyle.

The painting that is the image for this puzzle is fairly typical of Monet’s style during that stage of his career. He painted a number of them with Camille, or Camille and Jean, as their subjects. But usually, like this one, the people were used by Monet more as features to enhance the composition of a nature scene rather than as the subjects in portraits.

Monet told people that in his paintings he was not trying to portray people or things: He wanted to paint the intangible things like movement, light, air, and the weather, but that was impossible. Art Historian Henri Lallemand, in his book Monet: Impressions of Light says this about Monet’s Camille in Monet’s House at Argenteuil, painted in 1873: “Her figure has been painted sketchily and does not reveal any distinct features. Indeed, the treatment of the surface is the same the artist used for rendering the flowers around her.”

Jean was seven years old when the painting used for this puzzle was made. By then he had appeared in many paintings, but I don’t know how long he was ever expected to stay still and pose for any of them. I have no trouble imagining that young Jean was always thrilled to hear that the family was about to go on an outing, however my guess is that his heart sank somewhat whenever he saw that his father was packing up his painting gear for the occasion.

That reaction would probably have been particularly strong for this one, when Monet toted along the largest canvas he ever used in the 1870s – the painting is a metre tall. But he needn’t have worried too much. Art experts believe that this painting was completed in just a few hours.

Though the impressionists’ first show had been a failure, both Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir were eager to try again but with a less expensive venue, and they were able to persuade the others to go along with it. Woman with a parasol was among the 11 paintings and 7 pastel drawings that Monet contributed to their 1976 exhibition.

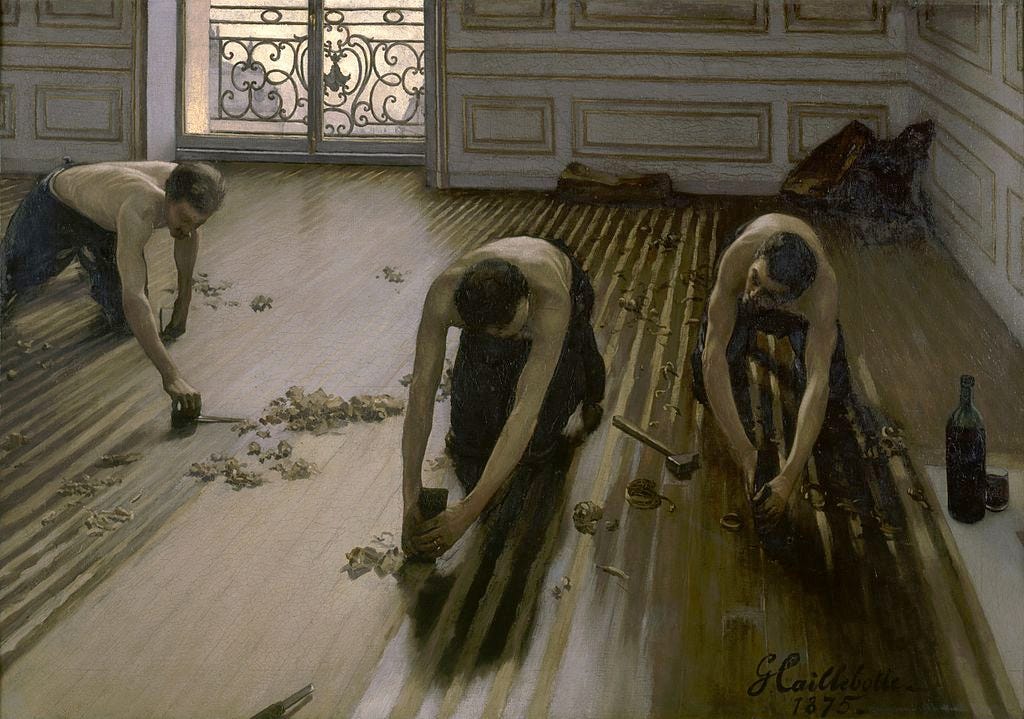

This time the artists still mostly got unfavourable reviews but they didn’t have as mocking of a tone as their first show. In fact, one of the paintings that had been rejected by the Salon jury got very favourable reviews. Even though it had the enormous scale and a finely-detailed painting style that suited the jury’s taste they had rejected it due to its “vulgar subject matter.” That painting was Gustave Caillebotte’s Les raboteurs de parquet (The Floor Scrapers.)

According to this website:

This impressive work was painted on an enormous scale and exhibits the academic style with which Caillebotte was taught to paint.

‘The Floor Planers’ is also one of the first examples of the urban working-class being depicted in art, though rural works and peasants had often been shown.

Caillebotte does not attach any moral message to his painting, he simply captures the scene with objective realism, from the tools to the gestures of the men and the strain of their muscles as they work on their hands and knees in a luxurious Parisian apartment.

Caillebotte’s painting was not in the impressionist style except that it portrayed everyday life, but is now credited with having begun turning the French art world away from confidence in the Salon as the arbiter of good taste, and paved the way for a willingness to consider what the impressionists had to offer. Attendance was all that high for this exhibition either, but more of the visitors were there came to see and study the artwork rather than ridicule it. And this time the modest admission charge did cover the exhibition’s costs.

Monet’s Woman with a parasol did not sell at the show, and an indication of his continuing precarious financial situation is that a short while later he needed to use the painting to pay for a medical bill. But the seeds had been sewn for French impressionism to become the highly-admired artistic movement that it is today.

Assembly walkthrough

I began with more of an image of this famous painting in my mind than usual. The general composition of it is hard to forget, and my memory had been refreshed when I bought the puzzle near the beginning of my spring-summer buying binge (which has since slowed down due to running out of storage space for them in my apartment, as well as overdue fiscal responsibility.) As always, the details were hazy but I did know that I could expect the shades of blue and white would be a cloud-mottled sky.

In the past I have begun this part of my review essays with a photo of my flipped and sorted pieces. This time I will give a brief walk-through of my sorting process.

I lined up the blue potential edge pieces along the top, and the green ones along the bottom. As I described in my review, many of the pieces, green, blue, and white, have sides that are perfect arcs of circles of various sizes. This lead me to suspect that there is something big going on in the cutting pattern and that they will link to each other so I grouped them together on the left side of the board.

This is what I mean about pieces having one or two sides that are the arc of a circle:

As usual, at this point I segregated the figural pieces and put them on the board upside-down since their unique shapes may be more important for their placement than their colours.

There are 14 blue pieces in the centre of the following photo that have two longish inside curves converging to meet at a trefoil shape.

As an experiment, I spent more time sorting than usual. In the process I discovered ten more trefoil pieces that had been hiding in with the curved ones bringing the total to 24. I also found many more pieces with semicircular sides and moved them to their appropriate groups. Unfortunately I forgot to take a photo after this final sort, but here is a closeup showing 23 of the 24 trefoil pieces:

One thing I noted even from just these loose pieces before assembly began was that there does not appear to be a clearly-defined horizon line between the blue sky and green land. Also, I had assembled two Monet puzzles before I started this newsletter/blog and expected more prominent brushwork than these pieces show. A quick check of the internet for the date of the painting showed that it had been painted fairly early in Monet’s career, before his brushwork became looser as he became more confident with the relaxed impressionist style.

Spoiler warning

As explained in the introduction, for this puzzle it seems important to put the assembly part of this essay below the spoiler warning because figuring out how all those curved and trefoil pieces work is largely what this puzzle is all about.

I began with assembly of the multi-piece whimsies and by connecting green apparent edge pieces and some of their colour-matched adjacent ones. The corners defined themselves fairly quickly with the help of the bunny and squirrel figurals. I completed the whole lower edge surprisingly quickly.

I continued with the diminishing number of green pieces, which included the placement of two multi-piece whimsies (a man and a woman facing each other, as shown in the photo of part of the backside that I included with my puzzle review.) The semi-circular pieces were a lot harder to place than I had expected.

The colour of the green end of the street-lamp whimsy and in another cluster that was emerging is the same of the foreground field, although their brush-strokes are smoother. At this point I still thought that they were part of that foreground but I eventually realized that they are the underside of the parasol.

The green part of the image is image is nearly complete …

… but there is plenty of puzzle yet to go.

I turned the puzzle around and began working from the top side. As you can see, the cluster around the parasol grew the fastest.

I found it rather disorienting to be upside down so I put it back right-side up and focused on the rest of the edges:

It was pretty slow going at this stage. All of the pieces that were left were blue & white, and I found those semi-circular pieces still to be quite tricky. But there were some brush work differences in different parts of Monet’s painting for me to work with and then, all of a sudden, it was as if the dam broke and I was able to place some of the clusters that I had been working on:

But then it went back to slow going again . . .

. . . and stayed that way right up until the end . . .

. . . until it was done!

Scroll down for photos of the backside of the puzzle and of the figural pieces.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Thanks for the interesting article Bill, I learned a few new things! One minor correction is that we do make both our lines of puzzles (Artifact - glossy images, and Ecru - matte images) at both our workshops now (Fremont CA, and Port Townsend WA). Also, it pains me to see how bad the back of our puzzles look, but we just haven't been able to find a good way to keep the backs beautiful without really increasing costs, and our assumption is 99% of puzzling is with the image face-up, so that's what we focus on, but I agree it would be nice if we could prettify our puzzle backs too, we'll keep R&D'ing that! -Maya (Owner, Artifact Puzzles)

Well, Bill, in the year or so since you've become an aficionado of these remarkable wooden puzzles, I have learned quite a lot. I myself am mostly still motivated to assemble cardboard puzzles of only medium complexity when I feel like relaxing with a jigsaw puzzle, but I do admire your research and the very close attention you pay to the assembly and analyses of your wooden puzzles. The way you have shown today how one can build trefoils and get small special pieces to combine into a further special outline (e.g., lamp on a table) within a completed puzzle really does impress me. It seems the puzzles you present to us have not only visual appeal, but also "plot." I don't know a lot about Monet, by the way, but I did order one of the Great Courses from The Teaching Company about Impressionist painters, so I may soon know more about Monet. Studying those courses on DVD is one of my devoted interests/hobbies. Thanks for all your work!